John

SEERY

United States of America

1941

East

(1973)

synthetic polymer paint on canvas

signed and titled verso c.l., red oilstick, "John Seery / East", not dated

294.9 (h)

x 579.5 (w)

cm

Purchased 1974

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

NGA 1974.129

- with André Emmerich Gallery, New York;

- from whom bought by the Australian National Gallery, May 1974

- Abstract Expressionism: the National Gallery of Australia celebrates the centenaries of Jackson Pollock and Morris Louis

- 14 Jul 2012 – 24 Feb 2013

- Phyllis Derfner, ‘New York letter’, Art International vol. 18 no. 1, 20 January 1974, p. 19;

- Peter Schjeldahl, ‘John Seery at Emmerich’, Art in America vol. 62 no. 2, March–April 1974, pp. 107–108, illus. col.

- Jane Bell, ‘John Seery—André Emmerich’, Arts Magazine vol. 48 no. 7, April 1974, p. 71, illus. p. 77;

- Elwyn Lynn, ‘Thoughts on Seery’, Art International vol. 18 no. 9, 15 November 1974, p. 50;

- Elwyn Lynn, ‘The light in the shadow of Blue poles’, Architecture Australia vol. 65 no. 2, April–May 1976, pp. 66, 67, illus. pp. 70–71;

- Robert Morris, ‘American quartet’, Art in America vol. 69 no. 10, December 1981, illus. p. 94.

In the 1970s Seery was at the forefront of a younger generation of painters who were associated with so-called Lyrical Abstraction. After the challenge of Minimalism and Conceptual Art in the 1960s, these artists were seen as reviving and reinvigorating a painterly ‘tradition’ in American art. In an article entitled ‘The new Informalists’ in 1970, the critic Carter Ratcliff argued that Seery, like a number of his contemporaries, had rejected the narrow trajectory of Clement Greenberg’s Modernism to reinstate line and colour as material, as paint. This, Ratcliff felt, placed them ‘after the “classic” color painters’, such as Morris Louis or Jules Olitski, yet reinforced the connection with Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s, and the work of Jackson Pollock in particular.[1]

In an ‘artist’s statement’ of 1975, Seery explained his approach:

Sometimes when I begin a painting I have an image of a color that I want to explore. I can be seduced by color. In fact, it is usually this seduction by a specific color that initiates the painting. Once I choose a color, I have to validate my choice. I do this by making the color rationalize itself on the canvas; as soon as that first color touches the canvas the rationalization begins. The initial color seeks to harmonize with the rest of the canvas (to me). It suggests options—flicking through a mental card catalogue of colors and when the right one comes I can feel it and apply it. Its purpose is to jolt the initial color into life. Other colors enrich and solve. Each new color must have its own identity and yet harmonize with each other. Each painting has its own logic and this logic is expressed through harmony.[2]

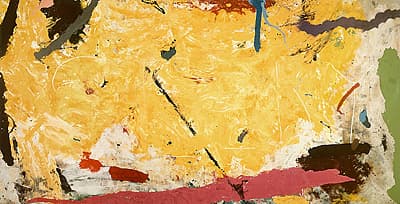

East 1973, with its dramatic sea of yellow suggesting daybreak, encapsulates the vitality and dynamism of Seery’s approach and technique of the mid 1970s. After stapling the ‘unfinished’ painting to the wall of his New York studio, the artist wrote his name in capital letters, ‘S-E-E-R-Y’, across the canvas ‘in an act of frustration’ before realising what he had accomplished in the work.[3] The partially obliterated letters remain as traces of the creative process. The black shaft or ‘pole’ in the middle of the painting acts an axis around which the rest of the elements revolve.

East was exhibited in the artist’s third solo show in 1974. Peter Schjeldahl, writing for Art in America, claimed that Seery’s show ‘confirmed his pre-eminence’ as ‘probably the strongest and most exciting abstract painter of the moment’.[4] Acquired by the National Gallery as a quintessential example of so-called Lyrical Abstraction, East was purchased in 1974, less than a year after Jackson Pollock’s Blue poles 1952.[5] The ‘pole’ that is utilised by Seery in East, as Schjeldahl observed, provided references to Pollock’s Blue poles, whereby the art historical debt of Lyrical Abstraction to Abstract Expressionism was captured through a dialogue in paint.

Steven Tonkin

[1] Carter Ratcliff, ‘The New Informalists’, ARTnews vol. 68 no. 10, February 1970, pp. 46–50.

[2] John Seery, ‘Artist’s statement’, Image, color and form: Recent paintings by eleven Americans, Toledo: The Toledo Museum of Art, 1975, p. 24.

[3] Seery, correspondence of 2002 with the National Gallery of Australia, NGA file 73/4888.

[4] Peter Schjeldahl, ‘John Seery at Emmerich’, Art in America vol. 62 no. 2, March–April 1974, p. 108; he went on to observe that: East was a ‘ravishing painting’ dominated by ‘blazing golden yellow, with broad swaths of red and green at its bottom and right edges and incidents of white, blue, purple and other colors elsewhere. A thin black diagonal is imbedded in its center—a device recalling Pollock’s Blue poles and effective here in a similar way. The singing, intensely rhythmic expanse of East can only be experienced; it can no more be described than it can really be seen, from whatever distance one views it. Its impact is operatic.’

[5] In the formation of the National Gallery’s collection, one aim was ‘to find key works representing major figures and styles which show the artist or movement at a moment of innovation, change or summation. See, for example, Patrick McCaughey, ‘The modern period’, in Australian National Gallery: An introduction, Canberra: Australian National Gallery 1982, p. 47.

Literature

- Phyllis Derfner, ‘New York letter’, Art International vol. 18 no. 1, 20 January 1974, p. 19;

- Peter Schjeldahl, ‘John Seery at Emmerich’, Art in America vol. 62 no. 2, March–April 1974, pp. 107–108, illus. col.

- Jane Bell, ‘John Seery—André Emmerich’, Arts Magazine vol. 48 no. 7, April 1974, p. 71, illus. p. 77;

- Elwyn Lynn, ‘Thoughts on Seery’, Art International vol. 18 no. 9, 15 November 1974, p. 50;

- Elwyn Lynn, ‘The light in the shadow of Blue poles’, Architecture Australia vol. 65 no. 2, April–May 1976, pp. 66, 67, illus. pp. 70–71;

- Robert Morris, ‘American quartet’, Art in America vol. 69 no. 10, December 1981, illus. p. 94.

Discussion of the work

In the 1970s Seery was at the forefront of a younger generation of painters who were associated with so-called Lyrical Abstraction. After the challenge of Minimalism and Conceptual Art in the 1960s, these artists were seen as reviving and reinvigorating a painterly ‘tradition’ in American art. In an article entitled ‘The new Informalists’ in 1970, the critic Carter Ratcliff argued that Seery, like a number of his contemporaries, had rejected the narrow trajectory of Clement Greenberg’s Modernism to reinstate line and colour as material, as paint. This, Ratcliff felt, placed them ‘after the “classic” color painters’, such as Morris Louis or Jules Olitski, yet reinforced the connection with Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s, and the work of Jackson Pollock in particular.[1]

In an ‘artist’s statement’ of 1975, Seery explained his approach:

Sometimes when I begin a painting I have an image of a color that I want to explore. I can be seduced by color. In fact, it is usually this seduction by a specific color that initiates the painting. Once I choose a color, I have to validate my choice. I do this by making the color rationalize itself on the canvas; as soon as that first color touches the canvas the rationalization begins. The initial color seeks to harmonize with the rest of the canvas (to me). It suggests options—flicking through a mental card catalogue of colors and when the right one comes I can feel it and apply it. Its purpose is to jolt the initial color into life. Other colors enrich and solve. Each new color must have its own identity and yet harmonize with each other. Each painting has its own logic and this logic is expressed through harmony.[2]

East 1973, with its dramatic sea of yellow suggesting daybreak, encapsulates the vitality and dynamism of Seery’s approach and technique of the mid 1970s. After stapling the ‘unfinished’ painting to the wall of his New York studio, the artist wrote his name in capital letters, ‘S-E-E-R-Y’, across the canvas ‘in an act of frustration’ before realising what he had accomplished in the work.[3] The partially obliterated letters remain as traces of the creative process. The black shaft or ‘pole’ in the middle of the painting acts an axis around which the rest of the elements revolve.

East was exhibited in the artist’s third solo show in 1974. Peter Schjeldahl, writing for Art in America, claimed that Seery’s show ‘confirmed his pre-eminence’ as ‘probably the strongest and most exciting abstract painter of the moment’.[4] Acquired by the National Gallery as a quintessential example of so-called Lyrical Abstraction, East was purchased in 1974, less than a year after Jackson Pollock’s Blue poles 1952.[5] The ‘pole’ that is utilised by Seery in East, as Schjeldahl observed, provided references to Pollock’s Blue poles, whereby the art historical debt of Lyrical Abstraction to Abstract Expressionism was captured through a dialogue in paint.

Steven Tonkin

[1] Carter Ratcliff, ‘The New Informalists’, ARTnews vol. 68 no. 10, February 1970, pp. 46–50.

[2] John Seery, ‘Artist’s statement’, Image, color and form: Recent paintings by eleven Americans, Toledo: The Toledo Museum of Art, 1975, p. 24.

[3] Seery, correspondence of 2002 with the National Gallery of Australia, NGA file 73/4888.

[4] Peter Schjeldahl, ‘John Seery at Emmerich’, Art in America vol. 62 no. 2, March–April 1974, p. 108; he went on to observe that: East was a ‘ravishing painting’ dominated by ‘blazing golden yellow, with broad swaths of red and green at its bottom and right edges and incidents of white, blue, purple and other colors elsewhere. A thin black diagonal is imbedded in its center—a device recalling Pollock’s Blue poles and effective here in a similar way. The singing, intensely rhythmic expanse of East can only be experienced; it can no more be described than it can really be seen, from whatever distance one views it. Its impact is operatic.’

[5] In the formation of the National Gallery’s collection, one aim was ‘to find key works representing major figures and styles which show the artist or movement at a moment of innovation, change or summation. See, for example, Patrick McCaughey, ‘The modern period’, in Australian National Gallery: An introduction, Canberra: Australian National Gallery 1982, p. 47.