Milton

RESNICK

Ukraine

1917

–

United States of America

2004

to United States of America 1922

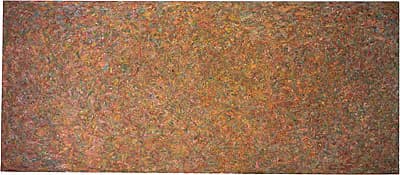

Pink fire

1971

oil on linen

signed and dated verso l.l., oil, "M. Resnick / 1971", inscribed verso c.r., fibre-tipped pen, "PINK FIRE"

224.3 (h)

x 519.0 (w)

cm

Purchased 1973

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

NGA 1973.1216

© Milton Resnick, Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery, New York.

- Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York;

- from whom bought by the Acquisitions Committee of the Australian National Gallery, April 1973

- Abstract Expressionism: the National Gallery of Australia celebrates the centenaries of Jackson Pollock and Morris Louis

- 14 Jul 2012 – 24 Feb 2013

- Jan Butterfield, ‘Texas’, Arts Magazine vol. 46 no. 1, September–October 1971, p. 55;

- Robert Hughes, ‘An iron will to form’, Time vol. 99 no. 22, 29 May 1972, p. 30;

- Ellen Lubell, ‘Reviews: New York galleries: Milton Resnick—Max Hutchinson’, Arts Magazine vol. 46 no. 8, Summer 1972, p. 60;

- Robert Hughes, ‘The last Salon’, Time vol. 101 no. 7, 12 February 1973, p. 52;

- Elwyn Lynn, ‘The light in the shadow of Blue Poles’, Architecture Australia vol. 65 no. 2, April–May 1976, p. 65;

- Linda L. Cathcart, Milton Resnick: Paintings 1945–1985, Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum 1985, illus. col. p. 55.

After living in Paris from 1946 to 1948, Milton Resnick returned to New York.[1] During the early 1950s he exhibited in a number of group shows, although it was not until 1955, at the age of thirty-eight, that he held his first solo exhibition in New York at the Poindexter Gallery. Despite his earlier affiliations, this led some critics and writers to categorise the artist as a ‘second generation’ Abstract Expressionist. Resnick definitely rejected this label and vehemently asserted his independence from the New York ‘art scene’.[2]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Resnick’s work underwent a series of shifts. He abandoned the ‘aggressive’ brushstrokes that distinguish paintings such as Low gate 1957, moving to a more lyrical and flickering use of the brush with a ‘naturalistic’ palette as in Tilt to the land 1959.[3] At this time his investigations led towards the application of paint in shorter dabs, resulting in a dappled effect and a more ‘overall’ composition. Resnick’s move to a huge loft studio in 1959 allowed him to work on increasingly monumental canvases, a feature that characterised much of his most significant work of the ensuing decades.

From the mid 1960s until the early 1970s, Resnick deliberately removed himself from New York.[4] In 1970-71 he was in New Mexico where he executed his so-titled, and landmark Roswell series. Pink fire 1971, now in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, is from this period.

As the title suggests, a pink ‘field’ of colour radiates from the painting, sending ripples across the gallery wall and engulfing the viewer. The frame of the work seems to be an arbitrary boundary, whereby the painting is only a ‘fragment’ of the artist’s ‘vision’.[5] Within Resnick’s work there is a converse relationship between size and the artist’s concentrated application of pigment. As the works become more expansive―Pink fire, for example, is over two metres high and five metres wide―it is the minutest details that give the work its dynamic ebb and flow across the surface. There are no brushstrokes of ‘pure’ colour, but rather a multitude of marbled microcosms composed of pink, yellow, orange, blue-green and dark-red oil paint. As Carter Ratcliff observed in a review of Resnick’s 1972 show at the Max Hutchinson Gallery:

They are heavily, repeatedly brushed, but with a focus of attention so intense it precipitates an endlessness in local incident. A painting … will have an overall tonality … This will be played off against a full range of color, most of it submerged by over-painting. This gives a visual meaning to the thickness of his paint surface: gesture and vision are joined. It also gives the surfaces an ambiguity: they could be considered thin in relation to the amount of color they contain and reveal.[6]

Resnick has described himself as a servant to paint, rather than its master.[7] He continued to work in a strictly non-figurative mode until the 1990s and throughout his career has remained committed to the impulses that drove a generation of American painters.

Steven Tonkin

[1] He re-established his friendship with the painter Willem de Kooning and was a founding member of the informal Eighth Street Club, which included Philip Guston, Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline and Mark Rothko.

[2] See, for example, his often-cited statement of 1962: ‘I am not the follower of Monet. I am not an admirer or follower of De Kooning. I am not an action painter. I am not an abstract expressionist. I am not younger than anybody or older. I will not take my hat off to any other living artist or dead in all the world’; first published in Allen S. Weller, Art: USA: Now, New York: Viking 1962, mp. 83; as a retort to Thomas B. Hess’s label and criticism, see for example Thomas B. Hess, ‘Reviews and previews: Milton Resnick’, Art News vol. 54 no. 8, December 1955, p. 51

[3] Low gate 1957 (Whitney Museums of American Art, New York) and Tilt to the land 1959 (private collection). This encouraged critics to allude to the late work of Monet, and to label Resnick as a contemporary Abstract Impressionist; see for example comments made by James Schuyler, ‘Six highlights this winter: Milton Resnick’, Art News vol. 58, no. 10, February 1960, p.43, Irving Sandler, The New York School: The painters and sculptors of the fifties, New York: Harper & Row 1978, p. 75, Jon R. Friedman, Arts Magazine vol. 54 no. 1, September 1979, p. 23. The artist likewise denied these associations with the landscape; see Linda L. Cathcart, Milton Resnick–Paintings 1945-1985, Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum, 1985, p. 11

[4] He accepted a post as a visiting professor of painting at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1966–67, then taking up an artist residency with the Roswell Museum and Art Center in south-eastern New Mexico during 1970–71,

[5] Cathcart, p. 9

[6] Carter Ratcliff, ‘New York letter’, Art International, vol. 26 no. 6, Summer 1972, p. 74

[7] In the artist’s words: “Paint … I wait upon it as a servant rather than a master.’ See Milton Resnick, ‘Statement’, in Cathcart 1985, p.73. he also comments: “The Act. The taking of paint and putting it down. The immediate impact on your psyche, your soul. Whatever it is that occurs when you empty your tube and raise that color. That has so much energy and danger in it. It’s such a magical important act in your life. So important you have to make a point of understanding that it is more important than anything else about art. Excerpts by Milton Resnick in ‘Out of the picture: A miscellany, Milton Resnick and the New York School’, unpublished ms by Geoffrey Dorfman, in Milton Resnick: A new decade, New York: Max Hutchinson Gallery 1982, p. [1]

The National Gallery of Australia holds two works on paper by Resnick, Untitled (1959) and Cragsmoor (1979).