Sydney

LONG

Australia

1871

–

London

1955

England, Europe 1910-21; Australia 1921- 22; England 1922-25; Australia 1925-52; England from 1952

71.7 (h) x 51.4 (w) cm

signed ‘SID LONG’ lower right Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, purchased 1969

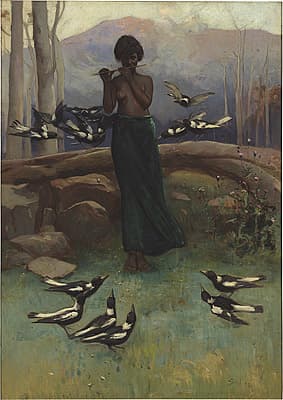

The music lesson, a sensitively coloured composition in delicate mauves, dull greens, pinks and browns, shot through with black and white, depicts a young Aboriginal woman, with one breast exposed in a conventional, classical reference (although she is too adolescent and contained for this to be erotic). She faces the viewer in the soft, purplish glow of an Australian dawn (or dusk), piping to a cluster of magpies that are mesmerised by her music. Demonstrating Long’s characteristic rejection of the expansive landscape vista in favour of quiet Australian gullies or more intimate bush corners, the painting highlights one way in which a preoccupation with classical mythology became, in this era, a lever in a system of cultural persuasion concerning Australia’s national identity.

Although Henry Lawson called for ‘Australian realism’ in a widely publicised debate with Banjo Paterson in 1892, for a significant number of fin de siècle poets and artists Australia was a land to be interpreted in Virgilian melodies and, as Bernard O’Dowd suggested in his poem, ‘The Bush’ (1912), a scroll on which we are to write mythologies of our own and epics new.’ Long’s ardent commitment to such views was expressed in 1905, soon after he painted The music lesson, in his article, ‘The trend of Australian art considered and discussed’ published in Art and Architecture 1905. Here, in a radical (and what proved to be a curiously isolated) departure from most of his classicist contemporaries, Long argued for the abandonment of foreign motifs, claiming that:

The Australian artist will never be able to people the bush with nymphs or the rivers with naiads … They will never look convincing among the gum trees … Instead of Pans and Centaurs he will bid the Aboriginal blossom out in all the graceful proportions of manly vigour.

If Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder had engaged in the late 19th century in fantasies of the Australian Arcady peopled with nymphs, Long radically extended this traditional allegorical association of woman with Nature by replacing their dancing, European creatures with an Aboriginal girl, who fulfils the function of Pan as embodiment of the natural spirit of Australia.

The use of Aboriginal people as a conveniently unique symbol of the Australian identity had increasing appeal in decades when the Aboriginal race no longer represented a threat to European settlement, and indeed was seen to be doomed. A sense of Australia’s ancientness, surviving unchanged to the present, fed poetic links between Australia and antiquity, and strong anthropological interest in Aboriginal culture also promoted the reinforcing conceit of the Aboriginal people as a link between the modern and the ancient worlds.

Painted after the theatrical flourishes of Long’s major Art Nouveau works, and in a more realistic vein, The music lesson foregrounds a figure who seems neither a fully mythological being nor a modern Aboriginal person: Long infers that she is not only a symbolic presence but a living embodiment of the archaic. In foregrounding her thus, he moves against the late-century, artistic domestication of the Australian bush to re-invest this environment with an element of mystery.

Who is teaching whom in The music lesson? Whilst it has long been held that the Aboriginal girl is teaching the magpies to sing, and occasionally that they may be teaching her their distinctive Australian song, it is also possible that ‘the music lesson’ is a lesson about what is uniquely Australian to be gleaned by the (white) viewer who responds to the strains of magpie song and Aboriginal spirit entwined. By invoking the Symbolist and Aestheticism-aligned concept of the capacity of music to suggest underlying emotional and psychological realms of reality, Long opens his work to

such interpretation.

If Long aimed in The music lesson to detour the European ‘tradition substitute’ of classical mythological figures, and to also imagine an alternative Australia to the rural myths of the Heidelberg school, he did so at the cost of a problematic mythologising of this country’s original owners. And yet, painted in the same year as Frederick McCubbin’s What the little girl saw in the bush 1904 (she saw fairies), and in a context where the colonialist involvement of white Australians with Aboriginal people largely structured them as invisible, Long’s portrayal of an Aboriginal figure in harmony with, even possession of, her Australian environment takes on, like Margaret Preston’s later appropriationist strategies, a more

complex hue.

Deborah Edwards

The music lesson, a sensitively coloured composition in delicate mauves, dull greens, pinks and browns, shot through with black and white, depicts a young Aboriginal woman, with one breast exposed in a conventional, classical reference (although she is too adolescent and contained for this to be erotic). She faces the viewer in the soft, purplish glow of an Australian dawn (or dusk), piping to a cluster of magpies that are mesmerised by her music. Demonstrating Long’s characteristic rejection of the expansive landscape vista in favour of quiet Australian gullies or more intimate bush corners, the painting highlights one way in which a preoccupation with classical mythology became, in this era, a lever in a system of cultural persuasion concerning Australia’s national identity.

Although Henry Lawson called for ‘Australian realism’ in a widely publicised debate with Banjo Paterson in 1892, for a significant number of fin de siècle poets and artists Australia was a land to be interpreted in Virgilian melodies and, as Bernard O’Dowd suggested in his poem, ‘The Bush’ (1912), a scroll on which we are to write mythologies of our own and epics new.’ Long’s ardent commitment to such views was expressed in 1905, soon after he painted The music lesson, in his article, ‘The trend of Australian art considered and discussed’ published in Art and Architecture 1905. Here, in a radical (and what proved to be a curiously isolated) departure from most of his classicist contemporaries, Long argued for the abandonment of foreign motifs, claiming that:

The Australian artist will never be able to people the bush with nymphs or the rivers with naiads … They will never look convincing among the gum trees … Instead of Pans and Centaurs he will bid the Aboriginal blossom out in all the graceful proportions of manly vigour.

If Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder had engaged in the late 19th century in fantasies of the Australian Arcady peopled with nymphs, Long radically extended this traditional allegorical association of woman with Nature by replacing their dancing, European creatures with an Aboriginal girl, who fulfils the function of Pan as embodiment of the natural spirit of Australia.

The use of Aboriginal people as a conveniently unique symbol of the Australian identity had increasing appeal in decades when the Aboriginal race no longer represented a threat to European settlement, and indeed was seen to be doomed. A sense of Australia’s ancientness, surviving unchanged to the present, fed poetic links between Australia and antiquity, and strong anthropological interest in Aboriginal culture also promoted the reinforcing conceit of the Aboriginal people as a link between the modern and the ancient worlds.

Painted after the theatrical flourishes of Long’s major Art Nouveau works, and in a more realistic vein, The music lesson foregrounds a figure who seems neither a fully mythological being nor a modern Aboriginal person: Long infers that she is not only a symbolic presence but a living embodiment of the archaic. In foregrounding her thus, he moves against the late-century, artistic domestication of the Australian bush to re-invest this environment with an element of mystery.

Who is teaching whom in The music lesson? Whilst it has long been held that the Aboriginal girl is teaching the magpies to sing, and occasionally that they may be teaching her their distinctive Australian song, it is also possible that ‘the music lesson’ is a lesson about what is uniquely Australian to be gleaned by the (white) viewer who responds to the strains of magpie song and Aboriginal spirit entwined. By invoking the Symbolist and Aestheticism-aligned concept of the capacity of music to suggest underlying emotional and psychological realms of reality, Long opens his work to

such interpretation.

If Long aimed in The music lesson to detour the European ‘tradition substitute’ of classical mythological figures, and to also imagine an alternative Australia to the rural myths of the Heidelberg school, he did so at the cost of a problematic mythologising of this country’s original owners. And yet, painted in the same year as Frederick McCubbin’s What the little girl saw in the bush 1904 (she saw fairies), and in a context where the colonialist involvement of white Australians with Aboriginal people largely structured them as invisible, Long’s portrayal of an Aboriginal figure in harmony with, even possession of, her Australian environment takes on, like Margaret Preston’s later appropriationist strategies, a more

complex hue.

Deborah Edwards

The music lesson, a sensitively coloured composition in delicate mauves, dull greens, pinks and browns, shot through with black and white, depicts a young Aboriginal woman, with one breast exposed in a conventional, classical reference (although she is too adolescent and contained for this to be erotic). She faces the viewer in the soft, purplish glow of an Australian dawn (or dusk), piping to a cluster of magpies that are mesmerised by her music. Demonstrating Long’s characteristic rejection of the expansive landscape vista in favour of quiet Australian gullies or more intimate bush corners, the painting highlights one way in which a preoccupation with classical mythology became, in this era, a lever in a system of cultural persuasion concerning Australia’s national identity.

Although Henry Lawson called for ‘Australian realism’ in a widely publicised debate with Banjo Paterson in 1892, for a significant number of fin de siècle poets and artists Australia was a land to be interpreted in Virgilian melodies and, as Bernard O’Dowd suggested in his poem, ‘The Bush’ (1912), a scroll on which we are to write mythologies of our own and epics new.’ Long’s ardent commitment to such views was expressed in 1905, soon after he painted The music lesson, in his article, ‘The trend of Australian art considered and discussed’ published in Art and Architecture 1905. Here, in a radical (and what proved to be a curiously isolated) departure from most of his classicist contemporaries, Long argued for the abandonment of foreign motifs, claiming that:

The Australian artist will never be able to people the bush with nymphs or the rivers with naiads … They will never look convincing among the gum trees … Instead of Pans and Centaurs he will bid the Aboriginal blossom out in all the graceful proportions of manly vigour.

If Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder had engaged in the late 19th century in fantasies of the Australian Arcady peopled with nymphs, Long radically extended this traditional allegorical association of woman with Nature by replacing their dancing, European creatures with an Aboriginal girl, who fulfils the function of Pan as embodiment of the natural spirit of Australia.

The use of Aboriginal people as a conveniently unique symbol of the Australian identity had increasing appeal in decades when the Aboriginal race no longer represented a threat to European settlement, and indeed was seen to be doomed. A sense of Australia’s ancientness, surviving unchanged to the present, fed poetic links between Australia and antiquity, and strong anthropological interest in Aboriginal culture also promoted the reinforcing conceit of the Aboriginal people as a link between the modern and the ancient worlds.

Painted after the theatrical flourishes of Long’s major Art Nouveau works, and in a more realistic vein, The music lesson foregrounds a figure who seems neither a fully mythological being nor a modern Aboriginal person: Long infers that she is not only a symbolic presence but a living embodiment of the archaic. In foregrounding her thus, he moves against the late-century, artistic domestication of the Australian bush to re-invest this environment with an element of mystery.

Who is teaching whom in The music lesson? Whilst it has long been held that the Aboriginal girl is teaching the magpies to sing, and occasionally that they may be teaching her their distinctive Australian song, it is also possible that ‘the music lesson’ is a lesson about what is uniquely Australian to be gleaned by the (white) viewer who responds to the strains of magpie song and Aboriginal spirit entwined. By invoking the Symbolist and Aestheticism-aligned concept of the capacity of music to suggest underlying emotional and psychological realms of reality, Long opens his work to

such interpretation.

If Long aimed in The music lesson to detour the European ‘tradition substitute’ of classical mythological figures, and to also imagine an alternative Australia to the rural myths of the Heidelberg school, he did so at the cost of a problematic mythologising of this country’s original owners. And yet, painted in the same year as Frederick McCubbin’s What the little girl saw in the bush 1904 (she saw fairies), and in a context where the colonialist involvement of white Australians with Aboriginal people largely structured them as invisible, Long’s portrayal of an Aboriginal figure in harmony with, even possession of, her Australian environment takes on, like Margaret Preston’s later appropriationist strategies, a more

complex hue.

Deborah Edwards