Sydney

LONG

Australia

1871

–

London

1955

England, Europe 1910-21; Australia 1921- 22; England 1922-25; Australia 1925-52; England from 1952

132.5 (w) x 107.0 (d) cm

signed ‘SYDNEY LONG’ lower right Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, purchased under the terms of the Florence Turner Blake Bequest 1971

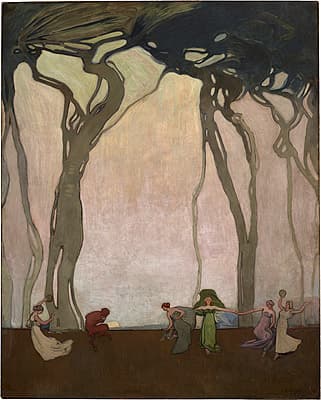

'Mr Sid Long … shows a remarkable picture … It is a wonderfully harmonious piece of imaginative work – really a poem on canvas and suggests a phantasy that may have evolved under the influence of a rapturous and somewhat weird piece of music … But whatever the influence, he has painted a picture of mystery without any of the dullness that is generally associated with such a theme, but which is full of light and fairy-like dreaminess and catches as fairy with a luminous charm and its dancing figures.'

So wrote the Sydney Mail reviewer on 24 November 1909 about Long’s missing 1909 painting, Pastoral. He could equally have been writing about Fantasy, Long’s reprise of this subject some five years later. The title ‘Fantasy’ conveys the idea that it is a poem on canvas, full of dreaminess and magic, and that it may have been created to a rapturous piece of music.

Around 1913–14 Long studied at the South London School of Technical Art, which had had an influential role on the development of Art Nouveau in Britain and, shortly after this, he began to re-work a number of his earlier Art Nouveau subjects, as in Fantasy.

He arranged the sinewy saplings into a decorative, curving pattern and composed the dancing figures in a decorative, Art Nouveau manner. But, in re-working the subject, Long made a number of changes (from what we can tell from the poor quality photograph that is all we now have of Pastoral 1909), turning a horizontal composition into a vertical one, and giving greater emphasis to the decorative arrangement of the trees. He also sharpened and refined the depiction of the forms, flattening them to line and shape, so that they resemble Tiffany glass.

Nonetheless, this work (as did Pastoral) shows Long’s ‘special gift for imaginative landscape by moonlight, with that suffusion of faintly purple haze whereby the whole is enveloped in an atmosphere of dreamy enchantment’ (SMH, 25 November 1909).

In Art Nouveau in Australia, Ron Radford suggested that the dancers in Fantasy show a distinct similarity to those in Leonardo Bistolfi’s poster for the international decorative art exhibition at Turin in 1902, which was reproduced in the Art Journal that year. And if Long had access to the German magazine Jugend, he could also have been influenced by the dancing figures in Ludwig von Zumbusch’s title page for that magazine in 1897. Long may also have been aware of Arthur Streeton’s symbolic painting, A bush idyll (‘What thou amongst the leaves hast never known’)1896 (AGNSW), an image of dancing nymphs in a bush setting. As in Long’s painting, Streeton’s work is suffused with a purple, dream-like haze, and the tall, spindly eucalypts tower over the figures to form an arch above them. Streeton’s nymphs are naked, giving his work a greater sensuality than Long’s more chaste, fairytale image.

Although Long may have reflected on the work of others, ultimately his image has a unique and magical presence.

'Mr Sid Long … shows a remarkable picture … It is a wonderfully harmonious piece of imaginative work – really a poem on canvas and suggests a phantasy that may have evolved under the influence of a rapturous and somewhat weird piece of music … But whatever the influence, he has painted a picture of mystery without any of the dullness that is generally associated with such a theme, but which is full of light and fairy-like dreaminess and catches as fairy with a luminous charm and its dancing figures.'

So wrote the Sydney Mail reviewer on 24 November 1909 about Long’s missing 1909 painting, Pastoral. He could equally have been writing about Fantasy, Long’s reprise of this subject some five years later. The title ‘Fantasy’ conveys the idea that it is a poem on canvas, full of dreaminess and magic, and that it may have been created to a rapturous piece of music.

Around 1913–14 Long studied at the South London School of Technical Art, which had had an influential role on the development of Art Nouveau in Britain and, shortly after this, he began to re-work a number of his earlier Art Nouveau subjects, as in Fantasy.

He arranged the sinewy saplings into a decorative, curving pattern and composed the dancing figures in a decorative, Art Nouveau manner. But, in re-working the subject, Long made a number of changes (from what we can tell from the poor quality photograph that is all we now have of Pastoral 1909), turning a horizontal composition into a vertical one, and giving greater emphasis to the decorative arrangement of the trees. He also sharpened and refined the depiction of the forms, flattening them to line and shape, so that they resemble Tiffany glass.

Nonetheless, this work (as did Pastoral) shows Long’s ‘special gift for imaginative landscape by moonlight, with that suffusion of faintly purple haze whereby the whole is enveloped in an atmosphere of dreamy enchantment’ (SMH, 25 November 1909).

In Art Nouveau in Australia, Ron Radford suggested that the dancers in Fantasy show a distinct similarity to those in Leonardo Bistolfi’s poster for the international decorative art exhibition at Turin in 1902, which was reproduced in the Art Journal that year. And if Long had access to the German magazine Jugend, he could also have been influenced by the dancing figures in Ludwig von Zumbusch’s title page for that magazine in 1897. Long may also have been aware of Arthur Streeton’s symbolic painting, A bush idyll (‘What thou amongst the leaves hast never known’)1896 (AGNSW), an image of dancing nymphs in a bush setting. As in Long’s painting, Streeton’s work is suffused with a purple, dream-like haze, and the tall, spindly eucalypts tower over the figures to form an arch above them. Streeton’s nymphs are naked, giving his work a greater sensuality than Long’s more chaste, fairytale image.

Although Long may have reflected on the work of others, ultimately his image has a unique and magical presence.

'Mr Sid Long … shows a remarkable picture … It is a wonderfully harmonious piece of imaginative work – really a poem on canvas and suggests a phantasy that may have evolved under the influence of a rapturous and somewhat weird piece of music … But whatever the influence, he has painted a picture of mystery without any of the dullness that is generally associated with such a theme, but which is full of light and fairy-like dreaminess and catches as fairy with a luminous charm and its dancing figures.'

So wrote the Sydney Mail reviewer on 24 November 1909 about Long’s missing 1909 painting, Pastoral. He could equally have been writing about Fantasy, Long’s reprise of this subject some five years later. The title ‘Fantasy’ conveys the idea that it is a poem on canvas, full of dreaminess and magic, and that it may have been created to a rapturous piece of music.

Around 1913–14 Long studied at the South London School of Technical Art, which had had an influential role on the development of Art Nouveau in Britain and, shortly after this, he began to re-work a number of his earlier Art Nouveau subjects, as in Fantasy.

He arranged the sinewy saplings into a decorative, curving pattern and composed the dancing figures in a decorative, Art Nouveau manner. But, in re-working the subject, Long made a number of changes (from what we can tell from the poor quality photograph that is all we now have of Pastoral 1909), turning a horizontal composition into a vertical one, and giving greater emphasis to the decorative arrangement of the trees. He also sharpened and refined the depiction of the forms, flattening them to line and shape, so that they resemble Tiffany glass.

Nonetheless, this work (as did Pastoral) shows Long’s ‘special gift for imaginative landscape by moonlight, with that suffusion of faintly purple haze whereby the whole is enveloped in an atmosphere of dreamy enchantment’ (SMH, 25 November 1909).

In Art Nouveau in Australia, Ron Radford suggested that the dancers in Fantasy show a distinct similarity to those in Leonardo Bistolfi’s poster for the international decorative art exhibition at Turin in 1902, which was reproduced in the Art Journal that year. And if Long had access to the German magazine Jugend, he could also have been influenced by the dancing figures in Ludwig von Zumbusch’s title page for that magazine in 1897. Long may also have been aware of Arthur Streeton’s symbolic painting, A bush idyll (‘What thou amongst the leaves hast never known’)1896 (AGNSW), an image of dancing nymphs in a bush setting. As in Long’s painting, Streeton’s work is suffused with a purple, dream-like haze, and the tall, spindly eucalypts tower over the figures to form an arch above them. Streeton’s nymphs are naked, giving his work a greater sensuality than Long’s more chaste, fairytale image.

Although Long may have reflected on the work of others, ultimately his image has a unique and magical presence.