Sydney

LONG

Australia

1871

–

London

1955

England, Europe 1910-21; Australia 1921- 22; England 1922-25; Australia 1925-52; England from 1952

35.3 (h) x 24.6 (w) cm

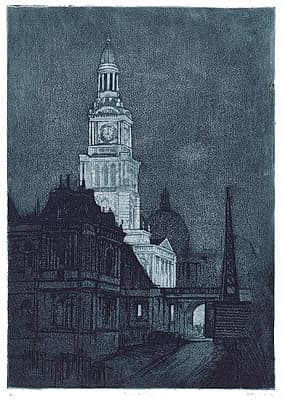

signed ‘Sydney Long ARE’ lower right, titled ‘The Town Hall. Floodlighted’ lower centre, inscribed ‘AP’ lower left below plate mark and ‘3/50’ lower left margin Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, gift of Miss B. Kelly 1958

In Long’s scene, Sydney Town Hall is floodlit against a velvety night sky punctuated by finely articulated architectural forms, such as the dome of the Queen Victoria Building. With the town hall clock set at nine, the rich shadows of evening are rendered through

the soft atmospheric effects of sandgrain

over the surface of the work.

Built on the site of Sydney’s first official European cemetery, the town hall was designed by architect J.H. Wilson and constructed from Pyrmont sandstone between 1868 and 1889. In 1934 the structure was destabilised during excavations for Town Hall Railway Station, and the portico was demolished. A new portico, rebuilt to the original design, was completed in time for the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester’s visit in November that year, when a state dinner was held in the Duke’s honour. In celebration of the event, the town hall was lit up, at the cost of £650 for ‘external decoration and illumination’ to the City Council (Townsville Daily Bulletin, 26 September 1934, p 5). First exhibited at the ‘Painter–Etchers’ and Graphic Art Society of Australia exhibition’, Sydney, in December 1934 (42), as ‘Floodlighted’, Long’s etching captures

the majesty of the occasion.

As Roger Butler has observed, Margaret Preston had similarly portrayed the illuminations displayed in June 1920 to honour of the Prince of Wales’s visit to Sydney, in a hand-coloured woodblock print, Illumination, 19th June 1920 (private collection). Royal visits were often celebrated with illuminations, though formerly with the use of gas lighting supplemented with flaming buckets of tar set on the roofs of buildings. By 1930, when the town hall was lit by Guglielmo Marconi via long-distance beam wireless from Genoa, the building was illuminated by 2800 lights. Of this event, the Sydney Mail reported on 2 April 1930: ‘Here is magic! Arabian nights recede into remoteness; their magic was nothing compared to this.’

Emma Kindred

In Long’s scene, Sydney Town Hall is floodlit against a velvety night sky punctuated by finely articulated architectural forms, such as the dome of the Queen Victoria Building. With the town hall clock set at nine, the rich shadows of evening are rendered through

the soft atmospheric effects of sandgrain

over the surface of the work.

Built on the site of Sydney’s first official European cemetery, the town hall was designed by architect J.H. Wilson and constructed from Pyrmont sandstone between 1868 and 1889. In 1934 the structure was destabilised during excavations for Town Hall Railway Station, and the portico was demolished. A new portico, rebuilt to the original design, was completed in time for the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester’s visit in November that year, when a state dinner was held in the Duke’s honour. In celebration of the event, the town hall was lit up, at the cost of £650 for ‘external decoration and illumination’ to the City Council (Townsville Daily Bulletin, 26 September 1934, p 5). First exhibited at the ‘Painter–Etchers’ and Graphic Art Society of Australia exhibition’, Sydney, in December 1934 (42), as ‘Floodlighted’, Long’s etching captures

the majesty of the occasion.

As Roger Butler has observed, Margaret Preston had similarly portrayed the illuminations displayed in June 1920 to honour of the Prince of Wales’s visit to Sydney, in a hand-coloured woodblock print, Illumination, 19th June 1920 (private collection). Royal visits were often celebrated with illuminations, though formerly with the use of gas lighting supplemented with flaming buckets of tar set on the roofs of buildings. By 1930, when the town hall was lit by Guglielmo Marconi via long-distance beam wireless from Genoa, the building was illuminated by 2800 lights. Of this event, the Sydney Mail reported on 2 April 1930: ‘Here is magic! Arabian nights recede into remoteness; their magic was nothing compared to this.’

Emma Kindred

In Long’s scene, Sydney Town Hall is floodlit against a velvety night sky punctuated by finely articulated architectural forms, such as the dome of the Queen Victoria Building. With the town hall clock set at nine, the rich shadows of evening are rendered through

the soft atmospheric effects of sandgrain

over the surface of the work.

Built on the site of Sydney’s first official European cemetery, the town hall was designed by architect J.H. Wilson and constructed from Pyrmont sandstone between 1868 and 1889. In 1934 the structure was destabilised during excavations for Town Hall Railway Station, and the portico was demolished. A new portico, rebuilt to the original design, was completed in time for the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester’s visit in November that year, when a state dinner was held in the Duke’s honour. In celebration of the event, the town hall was lit up, at the cost of £650 for ‘external decoration and illumination’ to the City Council (Townsville Daily Bulletin, 26 September 1934, p 5). First exhibited at the ‘Painter–Etchers’ and Graphic Art Society of Australia exhibition’, Sydney, in December 1934 (42), as ‘Floodlighted’, Long’s etching captures

the majesty of the occasion.

As Roger Butler has observed, Margaret Preston had similarly portrayed the illuminations displayed in June 1920 to honour of the Prince of Wales’s visit to Sydney, in a hand-coloured woodblock print, Illumination, 19th June 1920 (private collection). Royal visits were often celebrated with illuminations, though formerly with the use of gas lighting supplemented with flaming buckets of tar set on the roofs of buildings. By 1930, when the town hall was lit by Guglielmo Marconi via long-distance beam wireless from Genoa, the building was illuminated by 2800 lights. Of this event, the Sydney Mail reported on 2 April 1930: ‘Here is magic! Arabian nights recede into remoteness; their magic was nothing compared to this.’

Emma Kindred