Ivan

DURRANT

Australia

1947

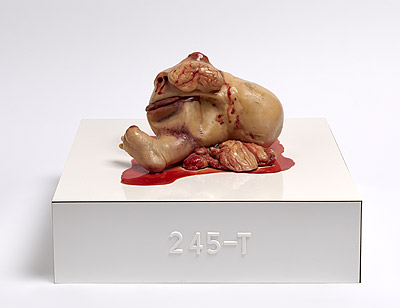

245-T

1980

oil and enamel varnish on synthetic polymer resin, perspex, composition board

Affixed plastic lettering, centre front "245-T"

23.5 (h)

x 35.7 (w)

x 35.7 (d)

cm

Gift of Ivan Durrant 1994

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

NGA 1994.3

Ivan Durrant is not unique in having a fondness for flesh. But he is exceptional in the way that he plays out the dichotomy of attraction and repulsion for flesh in his work. In 1975 he shocked Melbourne when he dumped a slaughtered cow in front of the National Gallery of Victoria. A few months later he had Sydney in an uproar when he exhibited what appeared to be a severed human hand at Hogarth Galleries. Then the public (perhaps no longer as credulous as they had been) was invited by Durrant to Wheelers Hill, on the outskirts of Melbourne, to see ‘Beverley the Amazing Performing Cow’ 1975. The performance was the slaughtering of Beverley. Durrant’s equation of flesh and death was understood broadly as a response to the life-wasting Vietnam War, but particularly the direct connection between life and death. Each of us, he argued, must ‘take responsibility for [their] own actions. If we are going to eat meat a cow dies for that. And we have to face it.’[1] Durrant’s fascination with flesh inevitably couples mortality and morality.

Pliable, fragile and vulnerable, softness is an apt trope for flesh. Quentin Crisp, never one to sentimentalise when a bon mot would do, suggested that ‘life was nothing more than a defiance of gravity’: the flesh of every being eventually collapses and pools. 245–T appears to show the corrosive disintegration of death; flesh softened to liquidity. It is a fleshy blob, an amalgam of protruding brain and Cyclops eye, with a tiny but perfect foot protruding, a Frankenstein, a foetus destined never to survive. While young flesh is normally enticing, Durrant elicits revulsion in this work.

Durrant showed 245–T in his 1982 exhibition, Uranium, you’re standing in it, held at the United Artists Gallery in Melbourne. His concern for humanity beleaguered by a toxic environment formed the basis for the display. ‘245–T’ or ‘2,4,5–Trichlorophenoxyacetic acid’, is a herbicide. It is also the major ingredient of Agent Orange, a chemical defoliant used in the Vietnam War. At the time that Durrant made this work, veterans of the war in the US, New Zealand and Australia were seeking compensation for the ill health caused by exposure to the herbicide. The chemicals were also linked to genetic defects and birth defects in infants. Some of the compounds were produced in Australia, and at the time it was thought that Agent Orange had been tested in the Innisfail region of Queensland. The effects of the toxin on the Vietnamese population are presumed to be considerable.

Durrant had worked for a short period at a prosthetics laboratory at Royal Melbourne Hospital and was able to create lifelike body parts, as well as convincing facsimiles of pig heads and various cuts of meat. In a review in The Age at the time of his Uranium exhibition, Durrant noted that the birth of monsters went unreported by local doctors, and that they were ‘left to die on the bench of the delivery room’.[2] The sterile white base of the sculpture evokes the hospital bench or a medical specimen table. The name on the front face is reminiscent of an epitaph.

Michael Desmond

Senior Curator

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

[1] Ivan Durrant, Realist painting �70s � �90s, Victorian Arts Centre, Melboure, 1992

[2] Ivan Durrant quoted in Memory Holloway, ‘Manipulating the media,’ The Age, 15 September 1982