Marcel

DUCHAMP

1887

–

1968

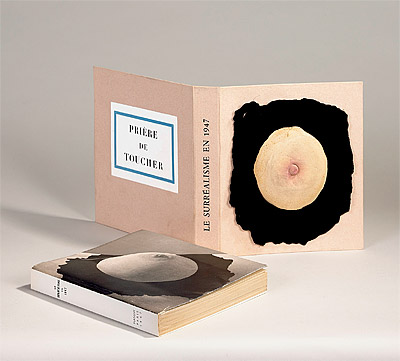

Le Surréalisme en 1947

[also known as Prière de toucher [Please touch]]

1947

illustrated book, multiple

89/999

edition of 999

book (closed)

25.0 (h)

x 22.8 (w)

cm

Orde Poynton Bequest, 2009

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

NGA 2009.52

© Marcel Duchamp. Licensed by ADAGP & VISCOPY, Australia

Marcel Duchamp was a leading figure of the Surrealist and Dada art movements. His introduction of the readymade into gallery spaces negated the very definition of fine art. The display of banal, mass-produced articles such as hair combs, bicycle wheels and bottle racks, eroded the boundaries between commercial value and aesthetic worth. The genius of Duchamp’s practice positioned him at the fore of the modernist avant-garde and his oeuvre exerted significant influence upon the development of Western art throughout the twentieth century.

Please touch (Prière de toucher) was designed for the cover of Le Surréalisme en 1947, the catalogue that accompanied the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme—the first post-war Surrealist art exhibition to be staged in Europe (July–August 1947). Centred upon the theme of myth, the exhibition was organised by Duchamp and André Breton. The two selected the Maeght Gallery in Paris as their venue, transforming the space (with the assistance of Austrian–American artist Frederick Keisler) into a complex labyrinth of orchestrated rooms intended to spiritually reawaken French society after the horrors of World War II. The limited edition catalogue was published by Maeght Editeur in a run of 999, with 49 books (numbered I–XLIX) signed by both Duchamp and Breton. Inset in the catalogue are 24 original prints by leading Surrealist artists including Max Ernst, Joan Miró and Yves Tanguy.[1]

Duchamp collaborated with Italian-born painter Enrico Donati on the design and production of the catalogue cover. Donati, based in New York City at the time, purchased 999 pre-fabricated foam and rubber breasts, otherwise known as ‘falsies’, from a warehouse in Brooklyn. Once in Paris, he and Duchamp undertook the protracted task of hand painting each readymade to more naturally resemble the female anatomy. Discussing the creative process, Donati recalled a conversation between himself and Duchamp: ’I remarked that I had never thought I would get tired of handling so many breasts, and Marcel said, ‘Maybe that’s the whole idea’.[2] Maria Martins, with whom Duchamp was having an intimate affair, is said to have modelled for the work. The completed breasts were adhered to a circular piece of black velvet and affixed to the cardboard slip-cover of the catalogue.

In the typically mischievous manner of Surrealism, Duchamp exploited the sexual tension of his erotically charged object. A blue-bordered label on the back of the catalogue playfully reads ‘please touch’; counter-intuitively inviting the viewer to experience the tactility of the work. While conventional art museums insisted upon a safe distance between object and viewer, the Surrealists implored their audience to actively engage with works of art presented in exhibition spaces. In the case of Please touch readers were literally forced to fondle the artificial breast adorning the cover before accessing the pages of the manuscript.

The brilliant daring of Please touch was to have a lasting impact upon European tastes and aesthetics. A year after the conclusion of the exhibition the Galerie Maeght was informed that a copy of the catalogue, which was posted to Geneva, had been seized by the Procureur Général of the Confederation, not because of its contents but because its cover was found to be ‘immoral’.[3] Duchamp’s wicked humour ensured that long after its production, controversy regarding the catalogue would reign.

Lisa McDonald

International Art

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

[1] The catalogue contains 24 original illustrations, including five colour lithographs by Victor Brauner, Max Ernst, Jacques Hérold, Wilfredo Lam and Joan Miró; five etchings (with one in colour) by Hans Bellmer, Marcel Jean, Maria Martins, Yves Tanguy and Dorothea Tanning; two woodcuts by Hans Arp; and 12 lithographs by Serge Brignoni, Alexander Calder, Bruno Capacci, Elizabeth van Damme, Julio de Diego, Enrico Donati, David Hare, Jacqueline Lamba, Roberto Matta, Kay Sage, Yves Tanguy and Toyen (Marie Čermínová)

[2] Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, ‘17 May 1947’, Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy 1887–1968, in Pontus Hulten (ed.), Marcel Duchamp, exhibition catalogue, Thames & Hudson, London, 1993, unpaginated

[3] Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, 1993, unpaginated 25/5/1948