Luke

ROBERTS

Australia

1952

All souls of the revolution

1976-94

mixed media

not signed, not dated

dimensions variable

Purchased 1996

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

NGA 1996.730.1-346

Luke Roberts’s practice embraces painting, performance, photography and video, as well as a peculiar form of curatorship. His Wunderkammer (literally ‘room of wonders’ or ‘miracle chamber’) replicates the magic of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century curiosity cabinets, the splendour of Victorian museums―with accompanying post-colonial ‘baggage’―and embraces chance encounters of the strange and commonplace.[1] Roberts celebrates kitsch and discourse on the Exotic, reinventing the cabinet of curiosities with conquests from op-shops, museum storage, antiquarian markets—and outer space. His Wunderkammer exists not in a private or museum collection but conceptually as an ever-expanding catalogue of items which will, eventually, encapsulate the whole world.[2]

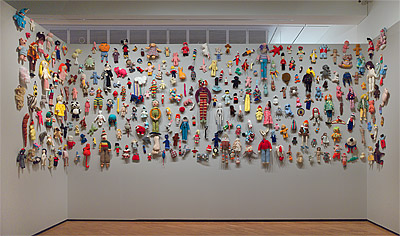

All souls of the revolution 1976–94 comprises about 350 dolls, clowns, gollywogs, rabbits, bears and other animals made of knitted wool, fabric, fur or synthetic materials. Originally part of the Wunderkammer/Kunstkamera project,[3] the work is hung high, in a frieze-like manner, extending above the line of the viewer’s eye to the ceiling. Roberts has compared his collection of toys to wingless angels, to the cupids and putti that adorn Baroque and Rococo ceilings.[4] The flamboyant theatricality of these styles encapsulates Roberts’s aesthetic approach. He also connects the sacred and the profane, drawing our attention to the apparent disjunction between ecclesiastical interiors and commonplace objects. Indeed, toys (either handmade or mass-produced in a factory) have a particular place in his oeuvre: these special friends now rejected or lost stand for the loss of childhood innocence, lives lost to AIDS and other scourges of the twentieth century.

The commemorative function of All souls of the revolution is reminiscent of roadside memorials, particularly the descanso tradition in which memorials are decorated for specific holidays, or those for children incorporating special toys. Roberts reminds us of the special role of toys and other gifts: handmade and homemade objects encapsulate the love between an adult and a child, and the child often perceives his or her world through such gifts. The objects in All souls of the revolution are intriguing, even if only for their sheer diversity. The intensity of their melange of colours and materials—efforts which are sometimes more indicative of sincerity than talent or skills—celebrates naiveté, the folkloric and the marginal, as well as ritualised spaces from cave paintings to church interiors.

All souls of the revolution takes its names from All Souls’ Day (2 November), a day that loomed large for the Catholic-educated Roberts. Also important for the artist are the visual and emotive resonances with Mexico, and Spanish-American traditions of the Days of the Dead (Dias de los Muertos), the collective celebration of Allhallows eve, All Saints’ Day and All Souls' Day.[5]

These toys form an understanding of, and a basis to concepts of mythology. They awaken within the child the capacity to be bigger than oneself, to project into another world … The passing of childhood is usually our first contact with death. The child we once were is lost and the remnants of our childhood are the archaeological evidence or fragments of its existence (Memory).

Roberts’s All souls of the revolution is both appealing in its immediacy, and as an embodiment of ‘otherness’. It also encapsulates an immensely political message: the power of group action and collective memory. The struggle against heterogeneity is not over yet, but when the revolution does come, it will be queer, extraordinary, full of love—and very, very funny.

Lucina Ward

Curator,

International Painting and Sculpture

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

[1] Michele Helmrich, ‘Wunderkammer/Kunstkamera, Luke Roberts’, Eyeline no 27, autumn/winter 1995, pp 22–27. Roberts has produced a number of Wunderkammer and one of the earliest was in 1990, at the State Library of Queensland, Brisbane; another, in the following year at Perspecta, comprised four cabinets, one of which, Wunderkammer: the voyage within the wonderful continues... 1991–94, is now in the collection of the Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney. In 1994–95 Roberts’s largest project to date was installed at the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, and in 1996 he produced an ‘Asian’ Wunderkammer for the Queensland Art Gallery’s Second Asia Pacific Triennial; both QAG projects are described by Timothy Morrell, in ‘The people’s pope: Luke Roberts’, Art and Australia, vol 35, no 2, 1997, pp 226–233

[2] Michele Helmrich, ‘Luke Roberts’, The second Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1996 p 121

[3] As Helmrich points out, Wunderkammer/Kunstkamera makes ‘a word-play of the ancient and the modern: the Greek kamara, the Latin for vault, camera, chamber (in camera), camera obscura, on camera. Further, Kunstkamera is a variation on Kunstkammer, those collections contemporary with the Wunderkammer which prioritised “art” and the artificial―Kunst being German for “art”. The title gives focus to the museum and the camera, and their repertoire of images.’ Quoted from Vanitas: Pope Alice presents Luke Roberts, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 1999, n17, p 23; see also Helmrich in The second Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1996 p 121

[4]The artist’s comments on the work are also drawn from this 1996 statement; see NGA 96/0183, folio 9

[5] In some areas of South America, a distinction is made between 1 November as the day to honour children and adults—Day of the Innocents (Día de los Inocentes) or Day of the Little Angels (Día de los Angelitos)—and 2 November as the day for deceased adults

Roberts cites Frida Kahlo as a key influence; she also features in his performance work