Misha HOLLENBACH

interview by Jaklyn Babington

An interview with the mysterious Perks! I know that you no longer go by that name but your early works were done under that pseudonym, and I wonder what the inspiration was behind it.

Actually, I have had many pseudonyms, and still do for various projects. I love that art exists as art, not that it’s a vehicle for an ego. Graffiti is interesting in the way that it is meant to be anonymous, but ultimately the perpetrator is concerned with fame and ego. It is far more alluring when making art (whether illegal or not) under a moniker to remain anonymous to perpetuate a myth. It is amusing when a person uses their real name to do graffiti, and equally amusing when someone uses their nom de plume as their ‘real’ name.

Can you tell us about the initial spark that got you so interested in street art as a form of artistic expression?

I think, more than street art, I had an early tendency for making art: painting, drawing, dressing up. I suppose growing up in the city, commuting on trains, the street provided an opportunity as a canvas/outlet for additional creative pursuits. Spray‑paint is merely another paint medium and, with a predisposition to painting and drawing, its instant appeal was obvious and dangerously exciting. Coupled with the release of [the 1984 hip‑hop film] Beat street and the amazing synthesizer sound of NYC dance music, this was a subculture that spoke in huge electronic volumes tome, having already a love for Italo disco.

The development of a number of Australian street artists is really interesting; everyone has a different story to tell. Can we try to fill-in some details about your creative past? Are you art‑school trained or self‑taught? Do you want to speak a little about your early career?

I completed a Fine Arts (Painting) degree, although this didn’t ignite any further interest in art, other than learning Deluxe Paint for Amiga computers, which had an amazing immediate effect on my creative pursuit—the digital age!

So, did you have a kind of mentor who guided your early development, or is there someone who particularly inspires you now? What kind of works really switch you on?

Max Ernst, Sigmar Polke, and Franz West inspire me. Their sheer creative pursuits,not specifically as painters, but as artists, and the scope of their careers commandabsolute admiration—and also possibilities for me as a creative human. As far as amentor, I’ve never looked to anyone for guidance or support. I’ve been completelyoverwhelmed and excited by discovering a world for myself. Saying that, there’s so many people’s work I see on a daily basis that I love … When I was younger, Andy Warhol was king and, although I still love his work, ideas and the legacy he has left, I suppose I have looked further afield than Pop and have been more inspired by aworld of esotericism and Dadaism in art.

I know that you did some early work with Shepard Fairey, which must have been a really experimental period for you. Can you tell us about this experience? It must have been quite amazing. What kind of street works did you collaborate on?

Shepard and I made friends in the mid 1990s and shared a studio and a house. He taught me screenprinting, and I showed him Xeroxing at various scales and then wheat‑pasting. We spent about a year wheat‑pasting bigger and bigger pictures in US and Mexican cities, both in galleries and on the street. There was a kinship in our excitement for scale, anonymous iconography and fabricated propaganda, and aninsatiable energy to make artwork … and for it to be seen!

In recent years, Australian street art has transitioned from the streets to the gallery. You have crossed over into the gallery context and are exhibiting under your real name. How long have you been exhibiting in galleries? Can you speak a little about your recent practice and how this might be informed by your street practice?

I don’t think my art has crossed over, it has more existed in parallel. Some art is best shown in galleries or in a publication or in a lounge room, and sometimes is best seen in an alley or a train or a doorway or freeway overpass. I think there’s a real freedom in art but, unfortunately, we have such a need to categorise into genders, genres, specifics. Some of the most interesting art, and other aspects of life, is when it is uncategorised or blurs and bleeds into different genres. This is when magic happens. Graffiti [and street] art can be boring and formulaic, and the same can be said for gallery art. It is when, perhaps, the art transcends both arenas, or can exist mutually in both, that it becomes really interesting. Graffiti [and street art] on a canvas isn’t enough, but capturing the energy of the street in a gallery is. I am interested in artists who have their roots in the street and how their street practice has now informed or been applied to a diversified practice—whether it be in galleries or in graphic design, fashion or alternative forms of commercial enterprise.

I know many people who are huge fans of your fashion label PAM—I have a couple of gorgeous pieces myself! Can you talk a little about PAM or your other alternative projects? How did these come about?

The street had a direct connection to starting PAM 10 years ago. PAM has goneon to be a renowned and respected cult label internationally, and it’s growing, with branches into publishing, music making, fashion and art. But its initial inception was in the form of a graffiti piece between Shauna and I that simply said PAM, short for Perks and Mini, on a wall which didn’t have sufficient room to spell our names. As far as street art informing our practice, its energy is what we tried to harness—colour, rebellion, fun—more so than printing street art onto a T‑shirt. Likewise with making non‑street artwork. The roots and energies of street art have been omnipresent but haven’t directly influenced the aesthetic. Methods and mediums of streetart—spray‑paint, stencilling—have been engaged sporadically, but the outcome has never been a direct copy of what happens on the street. It has been more a definite evolution of an aesthetic into something completely different to what we recognise as street art.

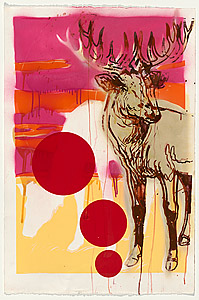

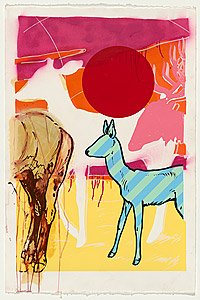

Let’s talk about the triptych work that we now have in the national art collection. It is a particular favourite in the Australian street art collection at the Gallery. In 2000, you started creating the No still eye deer series as a group of stencilled works on paper. Can you tell us about their original installation on the street and about these works as a series? Why the deer motif?

This series, No still eye deer, was a theme I was working with around 2002 and 2003. Initially, the deer were a symbol of the forgotten softness of nature, of making art. Graffiti art and associated subculture had become so masculine, so mac`ho. It was full of rules and men beating their chests. There was no room for women or for femineity or tenderness. The deer were a symbol of the beautiful nature of creativity, albeit street art, with parallels shared by graffiti. Nocturnal silence, stealth, grace. These deer as a visual icon stood as an antithesis to the gun toting, macho, hardline aesthetic of street art of the time. I made some series of screenprints, some publications and large‑scale 20‑metre‑long, 2‑storey‑high Xeroxes. I used pink and drips in a time of grey, black and blue, hard lines and angular connections.These deer stood against American graffiti and its conservative nature and rigid rules of machismo. In their street form, they made calming scenes amongst the debris of abandoned warehouses, and some slums in Mexico. On paper, they were explorations of the elements of stencilling, spray‑painting and screenprinting.

![Misha HOLLENBACH | No still eye deer [panel A] | 2000](images/sml/167523.jpg)

![Misha HOLLENBACH | No still eye deer [panel B] | 2000](images/sml/167522.jpg)

![Misha HOLLENBACH | No still eye deer [panel C] | 2000](images/sml/167524.jpg)