Cléopâtre [Cleopatra]

Choreographic drama in one act

- Producer: Les Ballets Russes de Serge Diaghilev

- First performed: As Une Nuit d’Egypte, 2 March 1908, Mariinsky Theatre, St Petersburg

- Paris premiere: 2 June 1909, Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris

- Revival: 5 September 1918, Coliseum Theatre, London

- Costume design: 1909 Léon Bakst; 1918 Sonia Delaunay

- Scenery design: 1909 Léon Bakst; 1918 Robert Delaunay

- Music: Anton Arensky, Alexander Taneyev, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Mikhail Glinka, Alexander Glazunov, Modeste Mussorgsky, Nicholas Tcherepnin

- Choreography: Michel Fokine

- Libretto: Michel Fokine

- Main characters: Cléopâtre (Cleopatra), Ta-Hor, Amoun, Cleopatra’s favourite slave, High Priest of the Temple, Bacchantes, Servants of the Temple, Grecian women, Grecian men, Silenes, Egyptian women, Egyptian men, Jews, Syrian musicians

The ballet is set during the reign of Cleopatra (51–30 BCE), Queen of Egypt, when two young lovers, Ta-Hor and Amoun, meet in the grounds of a temple. Their tryst is interrupted by the high priest of the temple announcing the arrival of Cleopatra and her court. On seeing Cleopatra, Amoun immediately falls in love with her. Ta-Hor attempts to re-engage her lover’s affections but to no avail. Amoun sends Cleopatra a message to which she responds that he can spend the night with her but in return he must drink poison in the morning. He agrees to the bargain and Ta-Hor later returns to the temple grounds to find the body of her dead lover.

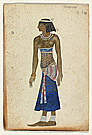

Cléopâtre was the most extraordinary production in the Ballets Russes’ 1909 season and signalled Léon Bakst’s mastery of sumptuous and exotic design. Against his powerful stage imagery of desert scenery and ancient Egyptian temple architecture and interior design, the dancers’ loose and abbreviated costumes glittered like jewels, animated by the physicality of their wearers. Bakst’s colour orchestration of gold, lapis blue, malachite green, pink, orange and violet was expressed in imagined Egyptian design motifs on the characters’ costumes, jewellery and weaponry. Dancer Ida Rubinstein’s dark, angular and unconventional beauty invested her role of Cleopatra with a mesmerising sensuality and, through Fokine’s choreographic innovations and Bakst’s revealing costumes, she and the other dancers showed that the whole body could be used for expressive effect. While the apparently bare sections of their bodies caused a sensation, the dancers were in fact wearing ‘fleshings’, flesh-toned silk or jersey inserts that simulated skin (and reduce the necessity and time for body make-up), a costumier’s technique used until 1912. These inserts seldom survive, nor are they evident in retouched contemporary stage photography.