Narcisse [Narcissus]

Mythological poem in one act

- Producer: Les Ballets Russes de Serge Diaghilev

- Premiere: 26 April 1911, Théâtre de Monte Carlo, Monaco

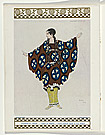

- Costume design: Léon Bakst

- Scenery design: Léon Bakst

- Music: Nicholas Tcherepnin

- Choreography: Michel Fokine

- Libretto: Léon Bakst

- Main characters: Echo, Narcisse, Bacchantes, Young Boeotian women, Nymphs

Filled with ancient Greek influences, the ballet is set in Boeotia (formally Cadmeis), in the north-eastern part of the Gulf of Corinth, at the shrine of Pomona, the goddess of fruit trees, gardens and orchards. The shrine is in a sylvan glade where a spring feeds into a glassy pool. The ballet tells the myth of Narcissus, a beautiful and self-indulgent youth, who spurns and ridicules the advances of the beautiful mountain-nymph Echo. In anger, Echo applies to Pomona to make Narcissus fall in love in a way that can never be reciprocated. Under Pomona’s spell, Narcissus promptly falls in love with his own reflection in the pool. He stands gazing at himself for so long that he sinks into the ground and a narcissus flower grows in his place.

Narcisse was the first of a trilogy of Greek-themed ballets designed by Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes’ 1911 and 1912 seasons. His research into the art of ancient Greece had begun in St Petersburg when preparing designs for productions there of the Greek tragedies Hippolytus, Antigone and Oedipus and Colonnus in 1902 and 1904. In 1905 Bakst had met Isadora Duncan, whose Greek dance style inspired his work with Michel Fokine on the Imperial Ballet’s production of Acis and Galatea later that year. In 1907, with miriskusniki colleague, painter Valentin Serov, Bakst travelled in Greece and Crete, visiting the ancient sites of Corfu, Olympia, Delphi and Knossos. His sketches from that trip reveal his fascination with the designs, patterns and colours of the dress he observed in ancient ceramics and sculpture. The soft wool muslin costumes for Narcisse—loose, pleated, short and open-necked—revealed the dancers’ arms and shoulders and allowed more expressive and fluid movement. The costumes’ colours and soft-edged patterns suggest the chalkiness and freshness of ancient fresco painting in a way quite different from the white formalism of the ancient world imagined by the neo-classicists.