CHUQUIBAMBA culture Southern highlands 1000 – 1475 AD

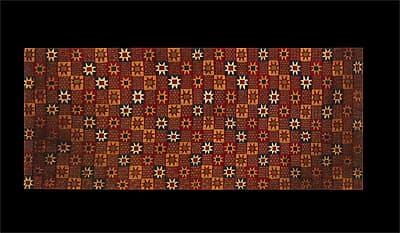

Textile length with 'tocapus' pattern 1000-1475 AD wool , tapestry weave218.8 (h) x 91.2 (w) cm National Gallery of Australia, Canberra NGA 1981.1089 Purchased 1981

The Chuquibamba culture has only recently been distinguished from the dominant Inca civilisation, which also used the eight-pointed star as a common motif. But it seems these southern mountain and river valley people of the Arequipa region in southern Peru produced sophisticated woven textiles such as this in the centuries before the Inca Empire arose. The culture flourished between about 1000 and 1475, but by 1470 was swept up and subsumed by the Inca Empire, its bright patterns adopted and re-used by the conquerors.

Large and spectacular in design, brilliant in colour, the woollen textile is most probably a length of woven cloth for a man’s poncho. It seems to be half the garment, with its identical other half missing. Either two lengths of fabric would have been sewn together, and an opening for the head made along the join, or more likely the garment was woven in one piece and the slit cut halfway along. Most costume was unstructured, and for practical reasons the poncho would have been fastened with a belt.

The cloth was woven from camelid wool, probably alpaca. Fibres were coloured using plant and mineral dyes—red, yellow, dark blue and green—as well as a natural cream. The pattern is extremely sophisticated, much more than the simple checkerboard as it appears at first glance. Squares encompass eight-pointed stars (tocapus), which have a square centre. They are woven in three colour ways: blue square with cream points and red centre; yellow square, red points, green centre; and red square, yellow points, blue centre. The stars alternate with squares filled by bird or fish designs, but reverse their direction diagonally, in a complex but satisfying geometry.

Due to its width, the poncho was probably woven on a vertical rather than a backstrap loom, or on a horizontal loom staked on the ground. The technique of alternating squares of interlocked tapestry weave with complementary weft weave was used.1 According to Mary Frame, the warp and weft yarns of Chuquibamba textiles were:

spun in Z direction, then doubled by plying in S direction … The vertical loom is particularly suitable to the weaving of interlocked tapestry, a structure favored for high status clothing in the highlands.2

Textiles such as these were wrapped as part of mummy bundles, or folded and placed in the tomb. Sometimes they were buried as offerings in a cache, rolled and stored in large ceramic urns. They were usually accompanied by loincloths, tunics and possibly headgear. It is not known if any funerary goods were used at all in life before their adoption as grave goods, but many of the most intricate textiles show no signs of being worn before burial. The cloths are in remarkably good condition, having been preserved in an extremely dry environment: their mountain origins were disguised by lively trade exchanges that meant they ended up in the arid coastal regions, where they survived.3 The Chuquibamba culture is named after the nearby modern town situated about 240 kilometres north-west of Arequipa.

Christine Dixon

1. Examined 8 July 2013 by Hannah Barrett and Micheline Ford from the Textile Conservation Department at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

2. Mary Frame, ‘Chuquibamba: A Highland textile style’, The Textile Museum Journal, vols 36 and 37, 1997–98, pp. 2–47, p. 5; she acknowledges the earlier research of Ann Pollard Rowe, ‘Provincial Inca tunics of the South Coast of Peru’, The Textile Museum Journal, vol. 33, 1992, pp. 5–52.

3. National Gallery of Australia catalogue entry by Andrew Fyfe, October 2003.

The Chuquibamba culture has only recently been distinguished from the dominant Inca civilisation, which also used the eight-pointed star as a common motif. But it seems these southern mountain and river valley people of the Arequipa region in southern Peru produced sophisticated woven textiles such as this in the centuries before the Inca Empire arose. The culture flourished between about 1000 and 1475, but by 1470 was swept up and subsumed by the Inca Empire, its bright patterns adopted and re-used by the conquerors.

Large and spectacular in design, brilliant in colour, the woollen textile is most probably a length of woven cloth for a man’s poncho. It seems to be half the garment, with its identical other half missing. Either two lengths of fabric would have been sewn together, and an opening for the head made along the join, or more likely the garment was woven in one piece and the slit cut halfway along. Most costume was unstructured, and for practical reasons the poncho would have been fastened with a belt.

The cloth was woven from camelid wool, probably alpaca. Fibres were coloured using plant and mineral dyes—red, yellow, dark blue and green—as well as a natural cream. The pattern is extremely sophisticated, much more than the simple checkerboard as it appears at first glance. Squares encompass eight-pointed stars (tocapus), which have a square centre. They are woven in three colour ways: blue square with cream points and red centre; yellow square, red points, green centre; and red square, yellow points, blue centre. The stars alternate with squares filled by bird or fish designs, but reverse their direction diagonally, in a complex but satisfying geometry.

Due to its width, the poncho was probably woven on a vertical rather than a backstrap loom, or on a horizontal loom staked on the ground. The technique of alternating squares of interlocked tapestry weave with complementary weft weave was used.1 According to Mary Frame, the warp and weft yarns of Chuquibamba textiles were:

spun in Z direction, then doubled by plying in S direction … The vertical loom is particularly suitable to the weaving of interlocked tapestry, a structure favored for high status clothing in the highlands.2

Textiles such as these were wrapped as part of mummy bundles, or folded and placed in the tomb. Sometimes they were buried as offerings in a cache, rolled and stored in large ceramic urns. They were usually accompanied by loincloths, tunics and possibly headgear. It is not known if any funerary goods were used at all in life before their adoption as grave goods, but many of the most intricate textiles show no signs of being worn before burial. The cloths are in remarkably good condition, having been preserved in an extremely dry environment: their mountain origins were disguised by lively trade exchanges that meant they ended up in the arid coastal regions, where they survived.3 The Chuquibamba culture is named after the nearby modern town situated about 240 kilometres north-west of Arequipa.

Christine Dixon

1. Examined 8 July 2013 by Hannah Barrett and Micheline Ford from the Textile Conservation Department at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

2. Mary Frame, ‘Chuquibamba: A Highland textile style’, The Textile Museum Journal, vols 36 and 37, 1997–98, pp. 2–47, p. 5; she acknowledges the earlier research of Ann Pollard Rowe, ‘Provincial Inca tunics of the South Coast of Peru’, The Textile Museum Journal, vol. 33, 1992, pp. 5–52.

3. National Gallery of Australia catalogue entry by Andrew Fyfe, October 2003.

The Chuquibamba culture has only recently been distinguished from the dominant Inca civilisation, which also used the eight-pointed star as a common motif. But it seems these southern mountain and river valley people of the Arequipa region in southern Peru produced sophisticated woven textiles such as this in the centuries before the Inca Empire arose. The culture flourished between about 1000 and 1475, but by 1470 was swept up and subsumed by the Inca Empire, its bright patterns adopted and re-used by the conquerors.

Large and spectacular in design, brilliant in colour, the woollen textile is most probably a length of woven cloth for a man’s poncho. It seems to be half the garment, with its identical other half missing. Either two lengths of fabric would have been sewn together, and an opening for the head made along the join, or more likely the garment was woven in one piece and the slit cut halfway along. Most costume was unstructured, and for practical reasons the poncho would have been fastened with a belt.

The cloth was woven from camelid wool, probably alpaca. Fibres were coloured using plant and mineral dyes—red, yellow, dark blue and green—as well as a natural cream. The pattern is extremely sophisticated, much more than the simple checkerboard as it appears at first glance. Squares encompass eight-pointed stars (tocapus), which have a square centre. They are woven in three colour ways: blue square with cream points and red centre; yellow square, red points, green centre; and red square, yellow points, blue centre. The stars alternate with squares filled by bird or fish designs, but reverse their direction diagonally, in a complex but satisfying geometry.

Due to its width, the poncho was probably woven on a vertical rather than a backstrap loom, or on a horizontal loom staked on the ground. The technique of alternating squares of interlocked tapestry weave with complementary weft weave was used.1 According to Mary Frame, the warp and weft yarns of Chuquibamba textiles were:

spun in Z direction, then doubled by plying in S direction … The vertical loom is particularly suitable to the weaving of interlocked tapestry, a structure favored for high status clothing in the highlands.2

Textiles such as these were wrapped as part of mummy bundles, or folded and placed in the tomb. Sometimes they were buried as offerings in a cache, rolled and stored in large ceramic urns. They were usually accompanied by loincloths, tunics and possibly headgear. It is not known if any funerary goods were used at all in life before their adoption as grave goods, but many of the most intricate textiles show no signs of being worn before burial. The cloths are in remarkably good condition, having been preserved in an extremely dry environment: their mountain origins were disguised by lively trade exchanges that meant they ended up in the arid coastal regions, where they survived.3 The Chuquibamba culture is named after the nearby modern town situated about 240 kilometres north-west of Arequipa.

Christine Dixon

1. Examined 8 July 2013 by Hannah Barrett and Micheline Ford from the Textile Conservation Department at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

2. Mary Frame, ‘Chuquibamba: A Highland textile style’, The Textile Museum Journal, vols 36 and 37, 1997–98, pp. 2–47, p. 5; she acknowledges the earlier research of Ann Pollard Rowe, ‘Provincial Inca tunics of the South Coast of Peru’, The Textile Museum Journal, vol. 33, 1992, pp. 5–52.

3. National Gallery of Australia catalogue entry by Andrew Fyfe, October 2003.