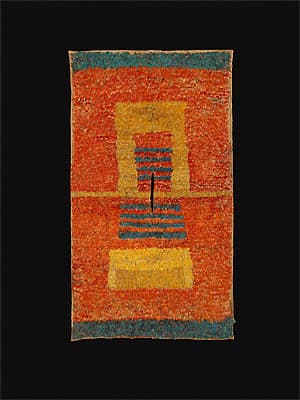

ICA-CHINCHA culture South coast 1100 – 1476 AD

Tabard [Feather poncho, with red, yellow and blue feathers in a highly abstract, possibly heraldic, design] c. 1300 AD feathers and cotton , sown142.0 (h) x 80.2 (w) cm National Gallery of Australia, Canberra NGA 1981.1924 Purchased 1981

The striking feather tabard has previously been attributed to Nazca, Huari and Inca makers. As the work has no provenance before the 1970s, and no similar design has been published, it is difficult to assign it to any culture with certainty. Scientific testing of the cotton backing and feathers has delivered slightly confusing results: the cotton dates to about 1200, and the feathers to about 1300.1 Unless the cotton was stored and used later, or the feather tested was part of later mending, it is hard to understand the anomaly.

A tabard is like a tunic, but with no side seams. Stylistically the garment, with its red, yellow and blue colour scheme, can be fitted into manufacture in the southern coastal Ica and Chincha river valleys in the centuries before the rise of the Inca Empire. Ica-Chincha craftspeople were skilled at featherwork (cat. 166), although their known output is more figurative and less sophisticated in design than the tabard. Definitely intended for the ruling elite, and probably for ceremonial use, it was buried with its owner as an offering to the gods. The work survived because of the arid conditions of the coastal desert climate.

Three yellow geometric shapes—rectangle, square ‘U’ and narrow stripe across the shoulders—and four sets of blue stripes contrast with a brilliant red-orange ground. The head slit does not tell us which side is the front. The tabard’s abstract motif has been read as ‘a gateway motif’,2 which would link it to Huari and Tiahuanaco predecessors. The feathers are those of:

[the] macaw, which lives in the tropical lowlands, hundreds of kilometres inland from the coast, so the feathers would have had to be traded from the highlands. It required much effort and expansive exchange networks to obtain them. The textile is a testament to the trading systems that have existed in Peru for thousands of years.3

The technique of featherwork was complex, as items:

such as tabards and hangings were covered by sewing strings of feathers—the feathers had been knotted into the strings in a separate process—to the fabric in overlapping horizontal rows, starting from the bottom.4

The small soft plumes employed probably came from the birds’ chests, as the long, stiff tail feathers were used to decorate headdresses and crowns.

Feathers were harvested on an industrial scale in Andean cultures, due to their spectacular colours and dramatic effect. The role of birds in traditional societies is often to:

signify spiritual energy and supernatural force … [and their plumes] are thought to empower ritual specialists with the capacity to bring forth good harvests, cure illness, foretell the future, and assure the well-being of the community.5

As they inhabited the upper world, birds and their feathers were associated with rulers and priests.

Christine Dixon

1. ANU Radiocarbon Dating Centre. S. J. Fallon, L. K. Fifield, J. M. Chappell, ‘The next chapter in radiocarbon dating at the Australian National University, 2010: Status report on the single stage AMS, Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research’. Two samples were taken from the feather tabard (81.1924), the cotton garment dates from 1148–1270 whilst the attached feather decoration dates from 1269–1390.

2. James W. Reid, Textile masterpieces of ancient Peru, New York: Dover 1986, pl. 46, illus. 72; see also James W. Reid, Magic feathers: Textile art from ancient Peru, London: Textile and Art 2005, p. 198, illus. pl. 71.

3. Research by Andrew Fyfe, 20 October 2003, National Gallery of Australia catalogue worksheets.

4. Heidi King, ‘Feather arts in ancient Peru’, in Heidi King et al., Peruvian featherworks: Art of the precolumbian era, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2012, p. 13.

5. King, p. 3.

The striking feather tabard has previously been attributed to Nazca, Huari and Inca makers. As the work has no provenance before the 1970s, and no similar design has been published, it is difficult to assign it to any culture with certainty. Scientific testing of the cotton backing and feathers has delivered slightly confusing results: the cotton dates to about 1200, and the feathers to about 1300.1 Unless the cotton was stored and used later, or the feather tested was part of later mending, it is hard to understand the anomaly.

A tabard is like a tunic, but with no side seams. Stylistically the garment, with its red, yellow and blue colour scheme, can be fitted into manufacture in the southern coastal Ica and Chincha river valleys in the centuries before the rise of the Inca Empire. Ica-Chincha craftspeople were skilled at featherwork (cat. 166), although their known output is more figurative and less sophisticated in design than the tabard. Definitely intended for the ruling elite, and probably for ceremonial use, it was buried with its owner as an offering to the gods. The work survived because of the arid conditions of the coastal desert climate.

Three yellow geometric shapes—rectangle, square ‘U’ and narrow stripe across the shoulders—and four sets of blue stripes contrast with a brilliant red-orange ground. The head slit does not tell us which side is the front. The tabard’s abstract motif has been read as ‘a gateway motif’,2 which would link it to Huari and Tiahuanaco predecessors. The feathers are those of:

[the] macaw, which lives in the tropical lowlands, hundreds of kilometres inland from the coast, so the feathers would have had to be traded from the highlands. It required much effort and expansive exchange networks to obtain them. The textile is a testament to the trading systems that have existed in Peru for thousands of years.3

The technique of featherwork was complex, as items:

such as tabards and hangings were covered by sewing strings of feathers—the feathers had been knotted into the strings in a separate process—to the fabric in overlapping horizontal rows, starting from the bottom.4

The small soft plumes employed probably came from the birds’ chests, as the long, stiff tail feathers were used to decorate headdresses and crowns.

Feathers were harvested on an industrial scale in Andean cultures, due to their spectacular colours and dramatic effect. The role of birds in traditional societies is often to:

signify spiritual energy and supernatural force … [and their plumes] are thought to empower ritual specialists with the capacity to bring forth good harvests, cure illness, foretell the future, and assure the well-being of the community.5

As they inhabited the upper world, birds and their feathers were associated with rulers and priests.

Christine Dixon

1. ANU Radiocarbon Dating Centre. S. J. Fallon, L. K. Fifield, J. M. Chappell, ‘The next chapter in radiocarbon dating at the Australian National University, 2010: Status report on the single stage AMS, Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research’. Two samples were taken from the feather tabard (81.1924), the cotton garment dates from 1148–1270 whilst the attached feather decoration dates from 1269–1390.

2. James W. Reid, Textile masterpieces of ancient Peru, New York: Dover 1986, pl. 46, illus. 72; see also James W. Reid, Magic feathers: Textile art from ancient Peru, London: Textile and Art 2005, p. 198, illus. pl. 71.

3. Research by Andrew Fyfe, 20 October 2003, National Gallery of Australia catalogue worksheets.

4. Heidi King, ‘Feather arts in ancient Peru’, in Heidi King et al., Peruvian featherworks: Art of the precolumbian era, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2012, p. 13.

5. King, p. 3.

The striking feather tabard has previously been attributed to Nazca, Huari and Inca makers. As the work has no provenance before the 1970s, and no similar design has been published, it is difficult to assign it to any culture with certainty. Scientific testing of the cotton backing and feathers has delivered slightly confusing results: the cotton dates to about 1200, and the feathers to about 1300.1 Unless the cotton was stored and used later, or the feather tested was part of later mending, it is hard to understand the anomaly.

A tabard is like a tunic, but with no side seams. Stylistically the garment, with its red, yellow and blue colour scheme, can be fitted into manufacture in the southern coastal Ica and Chincha river valleys in the centuries before the rise of the Inca Empire. Ica-Chincha craftspeople were skilled at featherwork (cat. 166), although their known output is more figurative and less sophisticated in design than the tabard. Definitely intended for the ruling elite, and probably for ceremonial use, it was buried with its owner as an offering to the gods. The work survived because of the arid conditions of the coastal desert climate.

Three yellow geometric shapes—rectangle, square ‘U’ and narrow stripe across the shoulders—and four sets of blue stripes contrast with a brilliant red-orange ground. The head slit does not tell us which side is the front. The tabard’s abstract motif has been read as ‘a gateway motif’,2 which would link it to Huari and Tiahuanaco predecessors. The feathers are those of:

[the] macaw, which lives in the tropical lowlands, hundreds of kilometres inland from the coast, so the feathers would have had to be traded from the highlands. It required much effort and expansive exchange networks to obtain them. The textile is a testament to the trading systems that have existed in Peru for thousands of years.3

The technique of featherwork was complex, as items:

such as tabards and hangings were covered by sewing strings of feathers—the feathers had been knotted into the strings in a separate process—to the fabric in overlapping horizontal rows, starting from the bottom.4

The small soft plumes employed probably came from the birds’ chests, as the long, stiff tail feathers were used to decorate headdresses and crowns.

Feathers were harvested on an industrial scale in Andean cultures, due to their spectacular colours and dramatic effect. The role of birds in traditional societies is often to:

signify spiritual energy and supernatural force … [and their plumes] are thought to empower ritual specialists with the capacity to bring forth good harvests, cure illness, foretell the future, and assure the well-being of the community.5

As they inhabited the upper world, birds and their feathers were associated with rulers and priests.

Christine Dixon

1. ANU Radiocarbon Dating Centre. S. J. Fallon, L. K. Fifield, J. M. Chappell, ‘The next chapter in radiocarbon dating at the Australian National University, 2010: Status report on the single stage AMS, Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research’. Two samples were taken from the feather tabard (81.1924), the cotton garment dates from 1148–1270 whilst the attached feather decoration dates from 1269–1390.

2. James W. Reid, Textile masterpieces of ancient Peru, New York: Dover 1986, pl. 46, illus. 72; see also James W. Reid, Magic feathers: Textile art from ancient Peru, London: Textile and Art 2005, p. 198, illus. pl. 71.

3. Research by Andrew Fyfe, 20 October 2003, National Gallery of Australia catalogue worksheets.

4. Heidi King, ‘Feather arts in ancient Peru’, in Heidi King et al., Peruvian featherworks: Art of the precolumbian era, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2012, p. 13.

5. King, p. 3.