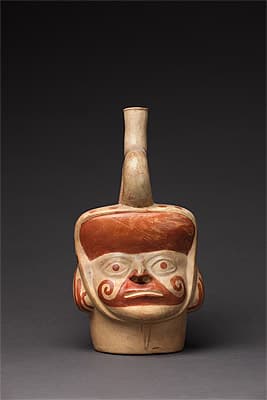

MOCHE culture North coast 100 – 800 AD

Portrait head stirrup vessel 100-800 AD ceramic , mould made, painted slip, fired23.4 (h) x 11.1 (w) x 12.3 (d) cm Museo Larco, Lima Photograph: Daniel Giannoni

Along with fine-line drawing, one of the Moche’s great artistic achievements was the portrait pot. It is a rare instance of an ancient civilisation producing very lifelike depictions of real people. Like other stirrup-spout vessels, portrait pots were used to hold liquid, but each pot also provided a three-dimensional individualised representation of a Moche man. All known pots of this type depict males, mostly adults, although a handful have been found that show young boys. Women were rarely depicted by the Moche, and when they were, it was largely in a subsidiary role.

The men portrayed on the pots range from fit and healthy, to disease-ridden or sporting battle scars. The man with a tightly bound head cloth around his head and chin (cat. 96) also appears on several other pots. He is known to have come from the Santa Valley and is identified by his distinctive puffy eyelids, swollen face, prominent chin and the scar below his lip.1 Many of these figures are depicted with similar prominent scars, although it is not clear if these were sustained in battle or from rituals.

Since many of these pots were looted, their exact placement in grave sites is not fully understood. Interestingly, it is thought that they were not necessarily buried with the person they depict. The ones unearthed during scientific excavations have been discovered in both men’s and women’s graves. It seems that many of these pots may have been used before being buried, and thus were not simply created as grave goods. While some versions are as small as six centimetres in height, and others as tall as 45 centimetres, most range around 15–30 centimetres. Portrait pots were made using moulds in a technique similar to other stirrup-spout pots (see cat. 90). This meant that multiple versions of the same pot could be produced, although painted differently so that no two identical ones exist.

Most plain pots were decorated by painting on multi-coloured slips of clay and water prior to firing. The black pots were made using a variety of firing techniques, including the smudge-firing method also used in Huari and Chimú pottery (see cats 53, 145). Some portraits display metal nose-jewellery, or a nose perforation indicates where such an ornament may have been attached.2 The portrait vessels admirably demonstrate the range of male headwear and the various ways Moche men covered their heads. The portraits with elaborate headdresses, such as the deer and double-headed-bird head rings seen on two of the portrait heads, also provide crucial information on how various ornaments found in grave sites were once worn (see cat. 66).

Although most portraits appear on the traditional Moche stirrup-spout pot, some take the form of bowls and jars, and pots with bridge handles. The portrait form evolved over time. During the early stages of the Moche culture, facial detail was less accurate, and the round heads were directly attached to legs in a rather fantastic fashion. In the middle of the Moche era, the portraits, seen in the depiction on one of the Museo Larco pots (cat. 95), were still quite stylised. While lifelike in appearance, it is somewhat generic and lacks the faithfulness of later portraits. The last phase of Moche culture, between approximately 500 and 650 AD,3 is considered the pinnacle of portrait pottery, when detailed fine-line techniques were applied to the patterning of the headdresses and other ornamentation. It is interesting that the Moche abandoned this type of ceramic in the final 100 to 200 years of their rule.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Meinrad Maria Grewenig (ed.), IncaGold: 3000 years of advanced civilisations—masterpieces from Peru’s Larco Museum, Heidelberg: Kehrer 2004, p. 140.

2. There is debate as to whether these metal nose ornaments were original or added recently, as no pots of this type have been found by archaeologists. See Christopher B. Donnan, Moche portraits from ancient Peru, Austin: University of Texas Press 2004, p. 41.

3. This dating is based on Rafael Larco Hoyle’s division of the Moche period into five phases. While not allocating precise dates, these are assumed to cover time spans of around 100 to 200 years.

Along with fine-line drawing, one of the Moche’s great artistic achievements was the portrait pot. It is a rare instance of an ancient civilisation producing very lifelike depictions of real people. Like other stirrup-spout vessels, portrait pots were used to hold liquid, but each pot also provided a three-dimensional individualised representation of a Moche man. All known pots of this type depict males, mostly adults, although a handful have been found that show young boys. Women were rarely depicted by the Moche, and when they were, it was largely in a subsidiary role.

The men portrayed on the pots range from fit and healthy, to disease-ridden or sporting battle scars. The man with a tightly bound head cloth around his head and chin (cat. 96) also appears on several other pots. He is known to have come from the Santa Valley and is identified by his distinctive puffy eyelids, swollen face, prominent chin and the scar below his lip.1 Many of these figures are depicted with similar prominent scars, although it is not clear if these were sustained in battle or from rituals.

Since many of these pots were looted, their exact placement in grave sites is not fully understood. Interestingly, it is thought that they were not necessarily buried with the person they depict. The ones unearthed during scientific excavations have been discovered in both men’s and women’s graves. It seems that many of these pots may have been used before being buried, and thus were not simply created as grave goods. While some versions are as small as six centimetres in height, and others as tall as 45 centimetres, most range around 15–30 centimetres. Portrait pots were made using moulds in a technique similar to other stirrup-spout pots (see cat. 90). This meant that multiple versions of the same pot could be produced, although painted differently so that no two identical ones exist.

Most plain pots were decorated by painting on multi-coloured slips of clay and water prior to firing. The black pots were made using a variety of firing techniques, including the smudge-firing method also used in Huari and Chimú pottery (see cats 53, 145). Some portraits display metal nose-jewellery, or a nose perforation indicates where such an ornament may have been attached.2 The portrait vessels admirably demonstrate the range of male headwear and the various ways Moche men covered their heads. The portraits with elaborate headdresses, such as the deer and double-headed-bird head rings seen on two of the portrait heads, also provide crucial information on how various ornaments found in grave sites were once worn (see cat. 66).

Although most portraits appear on the traditional Moche stirrup-spout pot, some take the form of bowls and jars, and pots with bridge handles. The portrait form evolved over time. During the early stages of the Moche culture, facial detail was less accurate, and the round heads were directly attached to legs in a rather fantastic fashion. In the middle of the Moche era, the portraits, seen in the depiction on one of the Museo Larco pots (cat. 95), were still quite stylised. While lifelike in appearance, it is somewhat generic and lacks the faithfulness of later portraits. The last phase of Moche culture, between approximately 500 and 650 AD,3 is considered the pinnacle of portrait pottery, when detailed fine-line techniques were applied to the patterning of the headdresses and other ornamentation. It is interesting that the Moche abandoned this type of ceramic in the final 100 to 200 years of their rule.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Meinrad Maria Grewenig (ed.), IncaGold: 3000 years of advanced civilisations—masterpieces from Peru’s Larco Museum, Heidelberg: Kehrer 2004, p. 140.

2. There is debate as to whether these metal nose ornaments were original or added recently, as no pots of this type have been found by archaeologists. See Christopher B. Donnan, Moche portraits from ancient Peru, Austin: University of Texas Press 2004, p. 41.

3. This dating is based on Rafael Larco Hoyle’s division of the Moche period into five phases. While not allocating precise dates, these are assumed to cover time spans of around 100 to 200 years.

Along with fine-line drawing, one of the Moche’s great artistic achievements was the portrait pot. It is a rare instance of an ancient civilisation producing very lifelike depictions of real people. Like other stirrup-spout vessels, portrait pots were used to hold liquid, but each pot also provided a three-dimensional individualised representation of a Moche man. All known pots of this type depict males, mostly adults, although a handful have been found that show young boys. Women were rarely depicted by the Moche, and when they were, it was largely in a subsidiary role.

The men portrayed on the pots range from fit and healthy, to disease-ridden or sporting battle scars. The man with a tightly bound head cloth around his head and chin (cat. 96) also appears on several other pots. He is known to have come from the Santa Valley and is identified by his distinctive puffy eyelids, swollen face, prominent chin and the scar below his lip.1 Many of these figures are depicted with similar prominent scars, although it is not clear if these were sustained in battle or from rituals.

Since many of these pots were looted, their exact placement in grave sites is not fully understood. Interestingly, it is thought that they were not necessarily buried with the person they depict. The ones unearthed during scientific excavations have been discovered in both men’s and women’s graves. It seems that many of these pots may have been used before being buried, and thus were not simply created as grave goods. While some versions are as small as six centimetres in height, and others as tall as 45 centimetres, most range around 15–30 centimetres. Portrait pots were made using moulds in a technique similar to other stirrup-spout pots (see cat. 90). This meant that multiple versions of the same pot could be produced, although painted differently so that no two identical ones exist.

Most plain pots were decorated by painting on multi-coloured slips of clay and water prior to firing. The black pots were made using a variety of firing techniques, including the smudge-firing method also used in Huari and Chimú pottery (see cats 53, 145). Some portraits display metal nose-jewellery, or a nose perforation indicates where such an ornament may have been attached.2 The portrait vessels admirably demonstrate the range of male headwear and the various ways Moche men covered their heads. The portraits with elaborate headdresses, such as the deer and double-headed-bird head rings seen on two of the portrait heads, also provide crucial information on how various ornaments found in grave sites were once worn (see cat. 66).

Although most portraits appear on the traditional Moche stirrup-spout pot, some take the form of bowls and jars, and pots with bridge handles. The portrait form evolved over time. During the early stages of the Moche culture, facial detail was less accurate, and the round heads were directly attached to legs in a rather fantastic fashion. In the middle of the Moche era, the portraits, seen in the depiction on one of the Museo Larco pots (cat. 95), were still quite stylised. While lifelike in appearance, it is somewhat generic and lacks the faithfulness of later portraits. The last phase of Moche culture, between approximately 500 and 650 AD,3 is considered the pinnacle of portrait pottery, when detailed fine-line techniques were applied to the patterning of the headdresses and other ornamentation. It is interesting that the Moche abandoned this type of ceramic in the final 100 to 200 years of their rule.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Meinrad Maria Grewenig (ed.), IncaGold: 3000 years of advanced civilisations—masterpieces from Peru’s Larco Museum, Heidelberg: Kehrer 2004, p. 140.

2. There is debate as to whether these metal nose ornaments were original or added recently, as no pots of this type have been found by archaeologists. See Christopher B. Donnan, Moche portraits from ancient Peru, Austin: University of Texas Press 2004, p. 41.

3. This dating is based on Rafael Larco Hoyle’s division of the Moche period into five phases. While not allocating precise dates, these are assumed to cover time spans of around 100 to 200 years.