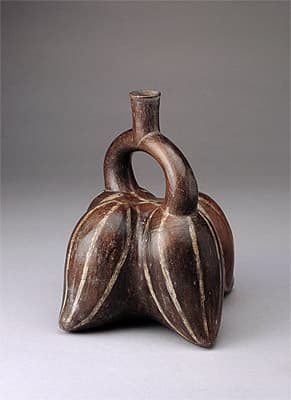

MOCHE culture North coast 100 – 800 AD

Stirrup vessel in the form of pepinos 100-800 AD ceramic17.7 (h) x 17.2 (w) x 17.4 (d) cm Museo Larco, Lima Photograph: Museo Larco

Alongside ceremonial and ritual imagery, the Moche commonly depicted everyday items on their pottery. The body of stirrup-shaped vessels, for example, often took the form of vegetation, especially representations of their staple food stuffs—maize, beans, yucca, squash, potato, peanuts—and locally grown gourds. The Moche farmed domesticated varieties of these plants, even in the arid coastal regions where agriculture was made possible with the aid of irrigation from mountain water sources. Although farming in the region predates the Moche, the culture developed its unique system of harnessing water through a system of canals.1

The potato (Solanum tuberosum), today considered a staple food across Europe, was introduced there following the Spanish conquest of Central and South America in the middle of the sixteenth century. Potatoes were an especially important crop in highland areas of ancient Peru, where only below-ground vegetables could be grown due to the very high altitudes. The potato was also extremely common in the coastal areas, where the Moche flourished. Another vegetable widely found along the Peruvian coast is the pepino (Solanum muricatum), a stripy melon of a soft, pulpy consistency, referred to by the Spanish as a cucumber. Both potato and pepino vessels comprise four of each vegetable arranged symmetrically around a central stirrup and spout. A common formation in this type of Moche pottery, it symbolised the four directions or the four corners of the world.2

Maize (Zea mays) was one of the most commonly depicted food stuff. Some pots were formed in moulds created from actual ears of corn to ensure accurate impressions, and thus provide botanists an exact and detailed morphology of ancient maize. In Peru, archaeological finds of preserved ancient maize are dated as early as 4300 BC. Many maize pots show the anthropomorphic fanged deity Ai Apaec, the Moche creator god, although he can can also be traced back to the Chavín feline god.3 Other Moche maize pots show a rat or, in the case of this pot, a bird nibbling on an ear of corn.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Elizabeth P. Benson, cat. 57, in Kathleen Berrin (ed.), The spirit of ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera, London: Thames and Hudson 1997, p. 122.

2. Benson, cats 58 and 59, in Berrin (ed.), p. 123.

3. Mary W. Eubanks, Corn in clay: Maize paleo-ethnobotany in pre-Columbian art, Gainsville: University Press of Florida 1999, pp. 30–31.

Alongside ceremonial and ritual imagery, the Moche commonly depicted everyday items on their pottery. The body of stirrup-shaped vessels, for example, often took the form of vegetation, especially representations of their staple food stuffs—maize, beans, yucca, squash, potato, peanuts—and locally grown gourds. The Moche farmed domesticated varieties of these plants, even in the arid coastal regions where agriculture was made possible with the aid of irrigation from mountain water sources. Although farming in the region predates the Moche, the culture developed its unique system of harnessing water through a system of canals.1

The potato (Solanum tuberosum), today considered a staple food across Europe, was introduced there following the Spanish conquest of Central and South America in the middle of the sixteenth century. Potatoes were an especially important crop in highland areas of ancient Peru, where only below-ground vegetables could be grown due to the very high altitudes. The potato was also extremely common in the coastal areas, where the Moche flourished. Another vegetable widely found along the Peruvian coast is the pepino (Solanum muricatum), a stripy melon of a soft, pulpy consistency, referred to by the Spanish as a cucumber. Both potato and pepino vessels comprise four of each vegetable arranged symmetrically around a central stirrup and spout. A common formation in this type of Moche pottery, it symbolised the four directions or the four corners of the world.2

Maize (Zea mays) was one of the most commonly depicted food stuff. Some pots were formed in moulds created from actual ears of corn to ensure accurate impressions, and thus provide botanists an exact and detailed morphology of ancient maize. In Peru, archaeological finds of preserved ancient maize are dated as early as 4300 BC. Many maize pots show the anthropomorphic fanged deity Ai Apaec, the Moche creator god, although he can can also be traced back to the Chavín feline god.3 Other Moche maize pots show a rat or, in the case of this pot, a bird nibbling on an ear of corn.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Elizabeth P. Benson, cat. 57, in Kathleen Berrin (ed.), The spirit of ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera, London: Thames and Hudson 1997, p. 122.

2. Benson, cats 58 and 59, in Berrin (ed.), p. 123.

3. Mary W. Eubanks, Corn in clay: Maize paleo-ethnobotany in pre-Columbian art, Gainsville: University Press of Florida 1999, pp. 30–31.

Alongside ceremonial and ritual imagery, the Moche commonly depicted everyday items on their pottery. The body of stirrup-shaped vessels, for example, often took the form of vegetation, especially representations of their staple food stuffs—maize, beans, yucca, squash, potato, peanuts—and locally grown gourds. The Moche farmed domesticated varieties of these plants, even in the arid coastal regions where agriculture was made possible with the aid of irrigation from mountain water sources. Although farming in the region predates the Moche, the culture developed its unique system of harnessing water through a system of canals.1

The potato (Solanum tuberosum), today considered a staple food across Europe, was introduced there following the Spanish conquest of Central and South America in the middle of the sixteenth century. Potatoes were an especially important crop in highland areas of ancient Peru, where only below-ground vegetables could be grown due to the very high altitudes. The potato was also extremely common in the coastal areas, where the Moche flourished. Another vegetable widely found along the Peruvian coast is the pepino (Solanum muricatum), a stripy melon of a soft, pulpy consistency, referred to by the Spanish as a cucumber. Both potato and pepino vessels comprise four of each vegetable arranged symmetrically around a central stirrup and spout. A common formation in this type of Moche pottery, it symbolised the four directions or the four corners of the world.2

Maize (Zea mays) was one of the most commonly depicted food stuff. Some pots were formed in moulds created from actual ears of corn to ensure accurate impressions, and thus provide botanists an exact and detailed morphology of ancient maize. In Peru, archaeological finds of preserved ancient maize are dated as early as 4300 BC. Many maize pots show the anthropomorphic fanged deity Ai Apaec, the Moche creator god, although he can can also be traced back to the Chavín feline god.3 Other Moche maize pots show a rat or, in the case of this pot, a bird nibbling on an ear of corn.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Elizabeth P. Benson, cat. 57, in Kathleen Berrin (ed.), The spirit of ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera, London: Thames and Hudson 1997, p. 122.

2. Benson, cats 58 and 59, in Berrin (ed.), p. 123.

3. Mary W. Eubanks, Corn in clay: Maize paleo-ethnobotany in pre-Columbian art, Gainsville: University Press of Florida 1999, pp. 30–31.