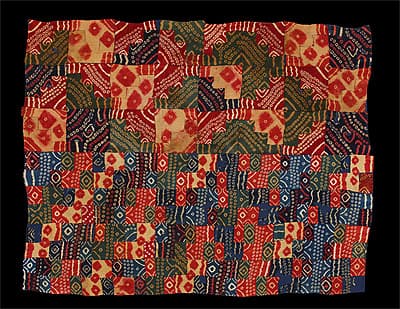

NAZCA culture South coast 100 – 700 AD

Mantle 100-700 AD wool135.0 (h) x 175.0 (w) cm Ministerio de Cultura del Perú: Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Photograph: Daniel Giannoni

Many fragments of these brilliantly coloured and intricate tie-dyed patchwork cloths survive. Large textiles, such as this one, are much less common. They are associated with the Late Nazca period, of about 500 to 700 AD, when the Huari culture was rising in the same area. Here, the mantle seems to have been assembled in two major zones. The upper half consists of two stepped-patterned pieces of separate designs and colours making up each square, with the other half made of small squares with smaller motifs, all joined together. Their complex geometry both delights and challenges the eye.

The same strong colours predominate in both halves: red, green, blue and dark blue are dyed by dipping cream and yellowish plain-weave cloth into baths of dyes, with ringed squares and lines protected to make the pattern. Sometimes the background cloth is protected, and the little diamonds or lines are dyed in red. Rather than a simple sewn patchwork joining however, a discontinuous warp and weft technique—similar to that seen in the Paracas stepped mantle (cat. 12)—was used. As described by Rebecca Stone-Miller, each shape of cloth was woven separately:

with its threads in both directions turning back rather than interlocking … Scaffold threads temporarily held [them] together … When the scaffold threads were pulled out, the variously coloured individual parts were reassembled with warps dovetailed and weft slits sewn.1

She notes that this technique is unique in the history of world textiles, and that it:

underscores how important it was to the ancient Andeans not to cut fabric, how much labor was expended to obtain a particular visual effect, and how central innovation was to the aesthetic system.2

Christine Dixon

1. Rebecca Stone-Miller, To weave for the sun: Ancient Andean textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston and London: Museum of Fine Arts and Thames and Hudson 1994, p. 101.

2. Stone-Miller, p. 101.

Many fragments of these brilliantly coloured and intricate tie-dyed patchwork cloths survive. Large textiles, such as this one, are much less common. They are associated with the Late Nazca period, of about 500 to 700 AD, when the Huari culture was rising in the same area. Here, the mantle seems to have been assembled in two major zones. The upper half consists of two stepped-patterned pieces of separate designs and colours making up each square, with the other half made of small squares with smaller motifs, all joined together. Their complex geometry both delights and challenges the eye.

The same strong colours predominate in both halves: red, green, blue and dark blue are dyed by dipping cream and yellowish plain-weave cloth into baths of dyes, with ringed squares and lines protected to make the pattern. Sometimes the background cloth is protected, and the little diamonds or lines are dyed in red. Rather than a simple sewn patchwork joining however, a discontinuous warp and weft technique—similar to that seen in the Paracas stepped mantle (cat. 12)—was used. As described by Rebecca Stone-Miller, each shape of cloth was woven separately:

with its threads in both directions turning back rather than interlocking … Scaffold threads temporarily held [them] together … When the scaffold threads were pulled out, the variously coloured individual parts were reassembled with warps dovetailed and weft slits sewn.1

She notes that this technique is unique in the history of world textiles, and that it:

underscores how important it was to the ancient Andeans not to cut fabric, how much labor was expended to obtain a particular visual effect, and how central innovation was to the aesthetic system.2

Christine Dixon

1. Rebecca Stone-Miller, To weave for the sun: Ancient Andean textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston and London: Museum of Fine Arts and Thames and Hudson 1994, p. 101.

2. Stone-Miller, p. 101.

Many fragments of these brilliantly coloured and intricate tie-dyed patchwork cloths survive. Large textiles, such as this one, are much less common. They are associated with the Late Nazca period, of about 500 to 700 AD, when the Huari culture was rising in the same area. Here, the mantle seems to have been assembled in two major zones. The upper half consists of two stepped-patterned pieces of separate designs and colours making up each square, with the other half made of small squares with smaller motifs, all joined together. Their complex geometry both delights and challenges the eye.

The same strong colours predominate in both halves: red, green, blue and dark blue are dyed by dipping cream and yellowish plain-weave cloth into baths of dyes, with ringed squares and lines protected to make the pattern. Sometimes the background cloth is protected, and the little diamonds or lines are dyed in red. Rather than a simple sewn patchwork joining however, a discontinuous warp and weft technique—similar to that seen in the Paracas stepped mantle (cat. 12)—was used. As described by Rebecca Stone-Miller, each shape of cloth was woven separately:

with its threads in both directions turning back rather than interlocking … Scaffold threads temporarily held [them] together … When the scaffold threads were pulled out, the variously coloured individual parts were reassembled with warps dovetailed and weft slits sewn.1

She notes that this technique is unique in the history of world textiles, and that it:

underscores how important it was to the ancient Andeans not to cut fabric, how much labor was expended to obtain a particular visual effect, and how central innovation was to the aesthetic system.2

Christine Dixon

1. Rebecca Stone-Miller, To weave for the sun: Ancient Andean textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston and London: Museum of Fine Arts and Thames and Hudson 1994, p. 101.

2. Stone-Miller, p. 101.