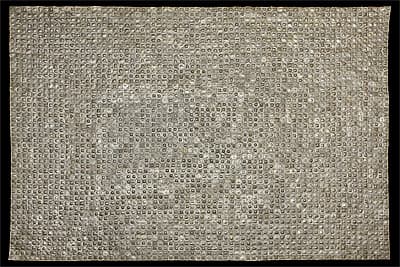

SICÁN-LAMBAYEQUE culture North coast 750 – 1375 AD

Mantle 900-1100 AD silver119.0 (h) x 168.0 (w) cm Ministerio de Cultura del Perú: Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Photograph: Daniel Giannoni

The mantle consists of 3288 small silver plates, organised in about 50 rows of 70 squares. Each plate has a central disc surrounded by a border of embossed circles, with four holes for attaching them. They were sewn by cotton thread onto a textile, forming part of the burial goods of the Lord of Lambayeque discovered by Julio C. Tello in 1936. The find was documented in Tello’s notebooks and an article published the next year in the Lima newspaper El Comercio.1

The Huaca Las Ventanas was one of 17 adobe huacas built at Batán Grande in the Middle Sicán period, between 900 and 1100 AD. Due to extraordinary large-scale and long-term looting of the site, situated on the Aurich family’s hacienda, almost no scientific investigation was possible until after the property was nationalised in Peru’s land reforms of the 1970s.

Although silver was often favoured in the Chimor Kingdom, over the gold preferred in the Middle Sicán period, Lambayeque smiths were as skilled with the medium as with other metals. By assembling hundreds of small plates into a cloak, the maker or makers achieved a rippling surface of shining silver. The garment, of conspicuous beauty and luxury, would enhance the prestige and power of a human deity on earth or in the grave.

Christine Dixon

1. Information kindly supplied by Luis Enrique Castillo Narrea, Head of Metals Collection and Conservation, Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Lima, 2 August 2013; Julio Tello, ‘Los trabajos arqueológicos en el Departamento de Lambayeque’, El Comercio, 29–31 January 1937.

2. See Roger Atwood, ‘The rape of Batán Grande’, Archaeology vol. 60 no. 4, July/August 2007, pp 29–33.

The mantle consists of 3288 small silver plates, organised in about 50 rows of 70 squares. Each plate has a central disc surrounded by a border of embossed circles, with four holes for attaching them. They were sewn by cotton thread onto a textile, forming part of the burial goods of the Lord of Lambayeque discovered by Julio C. Tello in 1936. The find was documented in Tello’s notebooks and an article published the next year in the Lima newspaper El Comercio.1

The Huaca Las Ventanas was one of 17 adobe huacas built at Batán Grande in the Middle Sicán period, between 900 and 1100 AD. Due to extraordinary large-scale and long-term looting of the site, situated on the Aurich family’s hacienda, almost no scientific investigation was possible until after the property was nationalised in Peru’s land reforms of the 1970s.

Although silver was often favoured in the Chimor Kingdom, over the gold preferred in the Middle Sicán period, Lambayeque smiths were as skilled with the medium as with other metals. By assembling hundreds of small plates into a cloak, the maker or makers achieved a rippling surface of shining silver. The garment, of conspicuous beauty and luxury, would enhance the prestige and power of a human deity on earth or in the grave.

Christine Dixon

1. Information kindly supplied by Luis Enrique Castillo Narrea, Head of Metals Collection and Conservation, Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Lima, 2 August 2013; Julio Tello, ‘Los trabajos arqueológicos en el Departamento de Lambayeque’, El Comercio, 29–31 January 1937.

2. See Roger Atwood, ‘The rape of Batán Grande’, Archaeology vol. 60 no. 4, July/August 2007, pp 29–33.

The mantle consists of 3288 small silver plates, organised in about 50 rows of 70 squares. Each plate has a central disc surrounded by a border of embossed circles, with four holes for attaching them. They were sewn by cotton thread onto a textile, forming part of the burial goods of the Lord of Lambayeque discovered by Julio C. Tello in 1936. The find was documented in Tello’s notebooks and an article published the next year in the Lima newspaper El Comercio.1

The Huaca Las Ventanas was one of 17 adobe huacas built at Batán Grande in the Middle Sicán period, between 900 and 1100 AD. Due to extraordinary large-scale and long-term looting of the site, situated on the Aurich family’s hacienda, almost no scientific investigation was possible until after the property was nationalised in Peru’s land reforms of the 1970s.

Although silver was often favoured in the Chimor Kingdom, over the gold preferred in the Middle Sicán period, Lambayeque smiths were as skilled with the medium as with other metals. By assembling hundreds of small plates into a cloak, the maker or makers achieved a rippling surface of shining silver. The garment, of conspicuous beauty and luxury, would enhance the prestige and power of a human deity on earth or in the grave.

Christine Dixon

1. Information kindly supplied by Luis Enrique Castillo Narrea, Head of Metals Collection and Conservation, Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Lima, 2 August 2013; Julio Tello, ‘Los trabajos arqueológicos en el Departamento de Lambayeque’, El Comercio, 29–31 January 1937.

2. See Roger Atwood, ‘The rape of Batán Grande’, Archaeology vol. 60 no. 4, July/August 2007, pp 29–33.