CHIMÚ culture North 1100 – 1470 AD

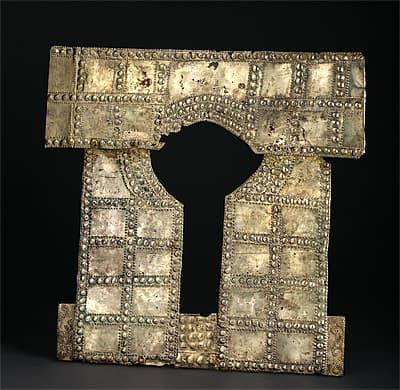

Pectoral 1100-1470 AD gold and copper46.1 (h) x 47.3 (w) cm Museo Oro del Perú, Lima Photograph: Daniel Giannoni

Chimú gold work was exceptionally intricate and often achieved by attaching many different pieces of gold to a central core. Here we find a matching set of ear and forehead ornaments with an array of dangling pendants (cats 163, 164). This exquisite assemblage of jewellery was discovered in the same grave near Trujillo in the Moche Valley. Similar sets have also been found in a grave in the Huarmey Valley.1

The forehead ornament, which was worn attached to a cloth head band, is in the shape of a feline’s face: it has a square mouth with stylised teeth, and a step pattern/wave motif border suggest the shape of a cat’s head and ears. At its temples, cut slivers of gold form feathers that mimic those commonly seen on other headdresses. Another bird association can be identified in the replacement of the cat’s nose with a beak. Other significant animals that appear on the ornaments are a pair of monkeys above the feline face, and two double-headed beetles or catfish below. Circular beads of inlaid silver have been used for the cat’s eyes. A wavy step pattern and a line of raised beading fill the remaining expanses of gold, and both also distinguish the ear ornaments.

The three Trujillo objects have multiple moveable parts. In the case of the tumbaga copper-gold alloy ear ornaments, six zig-zag sections have been cut out and suspended below each ornament’s centre, to which six half-moon shaped danglers have also been attached. These can alternatively be read as the rays of the sun, or the sinuous bodies of snakes with the half-moon shape their heads.

The pectoral (cat. 165) is also constructed from six sheets of gilded copper. Unlike the intricate designs of the ear and forehead ornaments, the pattern on the pectoral is laid out in a simple geometric grid of pressed circles and rows of raised dots. A stylised wave design created from hammered dots appears in the two small edge sections. Originally the pectoral would have had strips of fabric linking the top section of gold to the two side panels. The cloth bands were intended to lie over the shoulders, with one section of gold slung behind the neck and across the shoulder blades, and the other three sections hanging at the front across the chest. These fabric pieces no doubt disintegrated, and the three sections of gold sheet have subsequently been artificially joined.

Simeran Maxwell

1. See plates 55 and 56 in Elizabeth Hill Boone (ed.), Andean art at Dumbarton Oaks, vol. 1, Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks 1996, pp. 226, 232.

Chimú gold work was exceptionally intricate and often achieved by attaching many different pieces of gold to a central core. Here we find a matching set of ear and forehead ornaments with an array of dangling pendants (cats 163, 164). This exquisite assemblage of jewellery was discovered in the same grave near Trujillo in the Moche Valley. Similar sets have also been found in a grave in the Huarmey Valley.1

The forehead ornament, which was worn attached to a cloth head band, is in the shape of a feline’s face: it has a square mouth with stylised teeth, and a step pattern/wave motif border suggest the shape of a cat’s head and ears. At its temples, cut slivers of gold form feathers that mimic those commonly seen on other headdresses. Another bird association can be identified in the replacement of the cat’s nose with a beak. Other significant animals that appear on the ornaments are a pair of monkeys above the feline face, and two double-headed beetles or catfish below. Circular beads of inlaid silver have been used for the cat’s eyes. A wavy step pattern and a line of raised beading fill the remaining expanses of gold, and both also distinguish the ear ornaments.

The three Trujillo objects have multiple moveable parts. In the case of the tumbaga copper-gold alloy ear ornaments, six zig-zag sections have been cut out and suspended below each ornament’s centre, to which six half-moon shaped danglers have also been attached. These can alternatively be read as the rays of the sun, or the sinuous bodies of snakes with the half-moon shape their heads.

The pectoral (cat. 165) is also constructed from six sheets of gilded copper. Unlike the intricate designs of the ear and forehead ornaments, the pattern on the pectoral is laid out in a simple geometric grid of pressed circles and rows of raised dots. A stylised wave design created from hammered dots appears in the two small edge sections. Originally the pectoral would have had strips of fabric linking the top section of gold to the two side panels. The cloth bands were intended to lie over the shoulders, with one section of gold slung behind the neck and across the shoulder blades, and the other three sections hanging at the front across the chest. These fabric pieces no doubt disintegrated, and the three sections of gold sheet have subsequently been artificially joined.

Simeran Maxwell

1. See plates 55 and 56 in Elizabeth Hill Boone (ed.), Andean art at Dumbarton Oaks, vol. 1, Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks 1996, pp. 226, 232.

Chimú gold work was exceptionally intricate and often achieved by attaching many different pieces of gold to a central core. Here we find a matching set of ear and forehead ornaments with an array of dangling pendants (cats 163, 164). This exquisite assemblage of jewellery was discovered in the same grave near Trujillo in the Moche Valley. Similar sets have also been found in a grave in the Huarmey Valley.1

The forehead ornament, which was worn attached to a cloth head band, is in the shape of a feline’s face: it has a square mouth with stylised teeth, and a step pattern/wave motif border suggest the shape of a cat’s head and ears. At its temples, cut slivers of gold form feathers that mimic those commonly seen on other headdresses. Another bird association can be identified in the replacement of the cat’s nose with a beak. Other significant animals that appear on the ornaments are a pair of monkeys above the feline face, and two double-headed beetles or catfish below. Circular beads of inlaid silver have been used for the cat’s eyes. A wavy step pattern and a line of raised beading fill the remaining expanses of gold, and both also distinguish the ear ornaments.

The three Trujillo objects have multiple moveable parts. In the case of the tumbaga copper-gold alloy ear ornaments, six zig-zag sections have been cut out and suspended below each ornament’s centre, to which six half-moon shaped danglers have also been attached. These can alternatively be read as the rays of the sun, or the sinuous bodies of snakes with the half-moon shape their heads.

The pectoral (cat. 165) is also constructed from six sheets of gilded copper. Unlike the intricate designs of the ear and forehead ornaments, the pattern on the pectoral is laid out in a simple geometric grid of pressed circles and rows of raised dots. A stylised wave design created from hammered dots appears in the two small edge sections. Originally the pectoral would have had strips of fabric linking the top section of gold to the two side panels. The cloth bands were intended to lie over the shoulders, with one section of gold slung behind the neck and across the shoulder blades, and the other three sections hanging at the front across the chest. These fabric pieces no doubt disintegrated, and the three sections of gold sheet have subsequently been artificially joined.

Simeran Maxwell

1. See plates 55 and 56 in Elizabeth Hill Boone (ed.), Andean art at Dumbarton Oaks, vol. 1, Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks 1996, pp. 226, 232.