CHANCAY culture Lima 1200 – 1450 AD

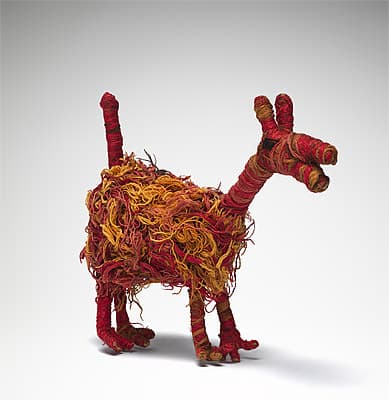

Llama 1100-1300 AD wool, cotton, reeds20.8 (h) x 26.8 (w) x 8.6 (d) cm National Gallery of Australia, Canberra NGA 1981.2268 Purchased 1981

These two charming woollen llamas form part of a group of small figurative sculptures commonly found in Chancay burial sites. Although often referred to as muñecas (‘doll’ in Spanish) or muñecas Chancay, there is no evidence that they were simply used as toys. Instead, they seem to have served as grave furnishings. It has also been suggested that, in some cases, these functions were related: having been owned by individuals in life, they were subsequently buried with them at death. Therefore, such an object sometimes represented a tool for use by the deceased, and was also an indicator of that person’s profession. When buried with a child, the figure may have served as a toy or, alternatively, as a companion for the afterlife.1 The ‘dolls’ also took the form of human figures and architectural structures as well as animals. In fact, small scenes incorporating multiple figures have often been found in graves.2 Unfortunately, the original locations where these two llamas were found are not known.

X-rays reveal that the larger dark-brown llama is stuffed with tiny round grains, slightly indented in the centre. Although not scientifically analysed, they are most likely very small kernels of corn. Many objects are known to have been stuffed with this commonly available grain (see cat. 148). While the seeds of modern corn are considerably larger and of a more distinctive tear-drop shape, ancient corn kernels varied significantly, from round, square, wide and flat, to a pointed diamond shape.3 Many types of corn also display similar indentations to those grains filling the brown llama.

Typical of many muñecas, the pink llama has an internal frame fashioned out of reeds. The creature’s head, distinctive ears, neck, legs, and its feet with strangely splayed toes, have been created using bundles of reeds bound with dyed camelid fibre. In pink and yellow, the same wool covers the fluffy exterior of the llama. The materials used in the object’s internal structure have been impossible to determine with certainty, even through x-ray. There is clear evidence of cotton wadding but whether grain stuffing was also used is not clear. Some of the human-shaped sculptures were created with small central openings, perhaps to insert special items. Alternatively, such figures may have functioned as puppets.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Ina Van Stan, ‘An ancient Peruvian rag doll’, Archaeology, vol. 15, no. 4, December 1962, p. 247.

2. Rebecca Stone-Miller, To weave for the sun: Andean textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts 1992, pp. 156–57.

3. Mary W. Eubanks, Corn in clay: Maize paleo-ethnobotany in pre-Columbian art, Gainesville: University Press of Florida 1999, p. 13.

These two charming woollen llamas form part of a group of small figurative sculptures commonly found in Chancay burial sites. Although often referred to as muñecas (‘doll’ in Spanish) or muñecas Chancay, there is no evidence that they were simply used as toys. Instead, they seem to have served as grave furnishings. It has also been suggested that, in some cases, these functions were related: having been owned by individuals in life, they were subsequently buried with them at death. Therefore, such an object sometimes represented a tool for use by the deceased, and was also an indicator of that person’s profession. When buried with a child, the figure may have served as a toy or, alternatively, as a companion for the afterlife.1 The ‘dolls’ also took the form of human figures and architectural structures as well as animals. In fact, small scenes incorporating multiple figures have often been found in graves.2 Unfortunately, the original locations where these two llamas were found are not known.

X-rays reveal that the larger dark-brown llama is stuffed with tiny round grains, slightly indented in the centre. Although not scientifically analysed, they are most likely very small kernels of corn. Many objects are known to have been stuffed with this commonly available grain (see cat. 148). While the seeds of modern corn are considerably larger and of a more distinctive tear-drop shape, ancient corn kernels varied significantly, from round, square, wide and flat, to a pointed diamond shape.3 Many types of corn also display similar indentations to those grains filling the brown llama.

Typical of many muñecas, the pink llama has an internal frame fashioned out of reeds. The creature’s head, distinctive ears, neck, legs, and its feet with strangely splayed toes, have been created using bundles of reeds bound with dyed camelid fibre. In pink and yellow, the same wool covers the fluffy exterior of the llama. The materials used in the object’s internal structure have been impossible to determine with certainty, even through x-ray. There is clear evidence of cotton wadding but whether grain stuffing was also used is not clear. Some of the human-shaped sculptures were created with small central openings, perhaps to insert special items. Alternatively, such figures may have functioned as puppets.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Ina Van Stan, ‘An ancient Peruvian rag doll’, Archaeology, vol. 15, no. 4, December 1962, p. 247.

2. Rebecca Stone-Miller, To weave for the sun: Andean textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts 1992, pp. 156–57.

3. Mary W. Eubanks, Corn in clay: Maize paleo-ethnobotany in pre-Columbian art, Gainesville: University Press of Florida 1999, p. 13.

These two charming woollen llamas form part of a group of small figurative sculptures commonly found in Chancay burial sites. Although often referred to as muñecas (‘doll’ in Spanish) or muñecas Chancay, there is no evidence that they were simply used as toys. Instead, they seem to have served as grave furnishings. It has also been suggested that, in some cases, these functions were related: having been owned by individuals in life, they were subsequently buried with them at death. Therefore, such an object sometimes represented a tool for use by the deceased, and was also an indicator of that person’s profession. When buried with a child, the figure may have served as a toy or, alternatively, as a companion for the afterlife.1 The ‘dolls’ also took the form of human figures and architectural structures as well as animals. In fact, small scenes incorporating multiple figures have often been found in graves.2 Unfortunately, the original locations where these two llamas were found are not known.

X-rays reveal that the larger dark-brown llama is stuffed with tiny round grains, slightly indented in the centre. Although not scientifically analysed, they are most likely very small kernels of corn. Many objects are known to have been stuffed with this commonly available grain (see cat. 148). While the seeds of modern corn are considerably larger and of a more distinctive tear-drop shape, ancient corn kernels varied significantly, from round, square, wide and flat, to a pointed diamond shape.3 Many types of corn also display similar indentations to those grains filling the brown llama.

Typical of many muñecas, the pink llama has an internal frame fashioned out of reeds. The creature’s head, distinctive ears, neck, legs, and its feet with strangely splayed toes, have been created using bundles of reeds bound with dyed camelid fibre. In pink and yellow, the same wool covers the fluffy exterior of the llama. The materials used in the object’s internal structure have been impossible to determine with certainty, even through x-ray. There is clear evidence of cotton wadding but whether grain stuffing was also used is not clear. Some of the human-shaped sculptures were created with small central openings, perhaps to insert special items. Alternatively, such figures may have functioned as puppets.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Ina Van Stan, ‘An ancient Peruvian rag doll’, Archaeology, vol. 15, no. 4, December 1962, p. 247.

2. Rebecca Stone-Miller, To weave for the sun: Andean textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts 1992, pp. 156–57.

3. Mary W. Eubanks, Corn in clay: Maize paleo-ethnobotany in pre-Columbian art, Gainesville: University Press of Florida 1999, p. 13.