HUARI culture 600 – 1000 AD

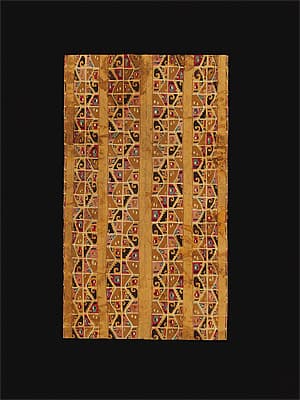

Tunic 500–800 AD wool and cotton , woven185.0 (h) x 106.8 (w) cm National Gallery of Australia, Canberra NGA 1982.1370 Purchased 1982

Among the most famous and numerous examples of Huari textiles are tapestry tunics that alternate plain strips with vertical abstract patterns. They are usually woven using warm chromatic hues: ochre, natural cream or white, dark yellow, tan, pink, blue and brown or black. Despite the highland origin of the Huari Empire, surviving textiles are found on the south coast, due to the dryness of the desert environment. The tunics are also portrayed on ceramic effigy jars, leading to the conclusion they possibly served as a uniform for state officials in the centralised Huari Empire.

The textile is made of two loom-widths of fabric, joined with a seam. Based on a winged attendant deity of the Sun God carved on Tiahuanaco’s Gateway of the Sun, fragmentary elements of the figure make up the abstracted schema. A curvilinear step-fret motif, representing the deity’s wings, alternates in offset rotational symmetry with the profile of its face: a split eye, tear drop (keyhole pattern) with S-shaped fangs. These form a series of four repeating panels that diagonally run the vertical of the textile. The design represents the Huari culture’s most renowned and creative adaptation of their iconography.1

The technique of tapestry, which occurs independently in disparate cultures around the world, in ancient and modern times:

lends itself to the creation of intricate, mosaic-like patterns made up of areas of pure, undiluted color that are woven into the cloth rather than added to a pre-existing fabric with needlework.2

Comparisons with Renaissance European tapestries favour the collective endeavour of the Huari, as they have much larger yarn counts (a measure of fineness and skill) and additionally their weavers ‘painstakingly finished the cloth on both its faces’.3 Although most patterns seem obsessively perfect, there is often an odd insertion of an extra motif or colour, as though the makers wished to assert their individual aesthetic choices into the large garment.

Christine Dixon

1. Adapted from National Gallery of Australia catalogue notes by Andrew Fyfe, 2003.

2. Susan E. Bergh, ‘Tapestry-woven tunics’, in Susan E. Bergh et al., Wari: Lords of the ancient Andes, New York: Cleveland Museum of Art and Thames and Hudson 2012, p. 160.

3. Bergh, p. 160.

Among the most famous and numerous examples of Huari textiles are tapestry tunics that alternate plain strips with vertical abstract patterns. They are usually woven using warm chromatic hues: ochre, natural cream or white, dark yellow, tan, pink, blue and brown or black. Despite the highland origin of the Huari Empire, surviving textiles are found on the south coast, due to the dryness of the desert environment. The tunics are also portrayed on ceramic effigy jars, leading to the conclusion they possibly served as a uniform for state officials in the centralised Huari Empire.

The textile is made of two loom-widths of fabric, joined with a seam. Based on a winged attendant deity of the Sun God carved on Tiahuanaco’s Gateway of the Sun, fragmentary elements of the figure make up the abstracted schema. A curvilinear step-fret motif, representing the deity’s wings, alternates in offset rotational symmetry with the profile of its face: a split eye, tear drop (keyhole pattern) with S-shaped fangs. These form a series of four repeating panels that diagonally run the vertical of the textile. The design represents the Huari culture’s most renowned and creative adaptation of their iconography.1

The technique of tapestry, which occurs independently in disparate cultures around the world, in ancient and modern times:

lends itself to the creation of intricate, mosaic-like patterns made up of areas of pure, undiluted color that are woven into the cloth rather than added to a pre-existing fabric with needlework.2

Comparisons with Renaissance European tapestries favour the collective endeavour of the Huari, as they have much larger yarn counts (a measure of fineness and skill) and additionally their weavers ‘painstakingly finished the cloth on both its faces’.3 Although most patterns seem obsessively perfect, there is often an odd insertion of an extra motif or colour, as though the makers wished to assert their individual aesthetic choices into the large garment.

Christine Dixon

1. Adapted from National Gallery of Australia catalogue notes by Andrew Fyfe, 2003.

2. Susan E. Bergh, ‘Tapestry-woven tunics’, in Susan E. Bergh et al., Wari: Lords of the ancient Andes, New York: Cleveland Museum of Art and Thames and Hudson 2012, p. 160.

3. Bergh, p. 160.

Among the most famous and numerous examples of Huari textiles are tapestry tunics that alternate plain strips with vertical abstract patterns. They are usually woven using warm chromatic hues: ochre, natural cream or white, dark yellow, tan, pink, blue and brown or black. Despite the highland origin of the Huari Empire, surviving textiles are found on the south coast, due to the dryness of the desert environment. The tunics are also portrayed on ceramic effigy jars, leading to the conclusion they possibly served as a uniform for state officials in the centralised Huari Empire.

The textile is made of two loom-widths of fabric, joined with a seam. Based on a winged attendant deity of the Sun God carved on Tiahuanaco’s Gateway of the Sun, fragmentary elements of the figure make up the abstracted schema. A curvilinear step-fret motif, representing the deity’s wings, alternates in offset rotational symmetry with the profile of its face: a split eye, tear drop (keyhole pattern) with S-shaped fangs. These form a series of four repeating panels that diagonally run the vertical of the textile. The design represents the Huari culture’s most renowned and creative adaptation of their iconography.1

The technique of tapestry, which occurs independently in disparate cultures around the world, in ancient and modern times:

lends itself to the creation of intricate, mosaic-like patterns made up of areas of pure, undiluted color that are woven into the cloth rather than added to a pre-existing fabric with needlework.2

Comparisons with Renaissance European tapestries favour the collective endeavour of the Huari, as they have much larger yarn counts (a measure of fineness and skill) and additionally their weavers ‘painstakingly finished the cloth on both its faces’.3 Although most patterns seem obsessively perfect, there is often an odd insertion of an extra motif or colour, as though the makers wished to assert their individual aesthetic choices into the large garment.

Christine Dixon

1. Adapted from National Gallery of Australia catalogue notes by Andrew Fyfe, 2003.

2. Susan E. Bergh, ‘Tapestry-woven tunics’, in Susan E. Bergh et al., Wari: Lords of the ancient Andes, New York: Cleveland Museum of Art and Thames and Hudson 2012, p. 160.

3. Bergh, p. 160.