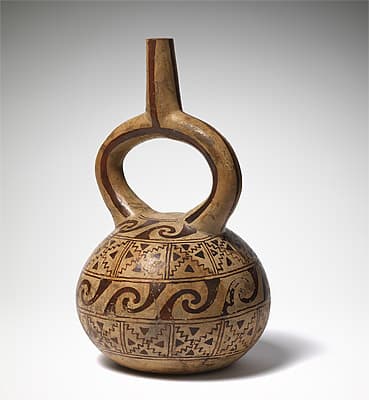

MOCHE culture North coast 100 – 800 AD

Stirrup vessel with a geometric design c. 600 AD ceramic24.0 (h) cm 14.5 cm (diameter) National Gallery of Australia, Canberra NGA 1983.293 Purchased 1983

Moche ceramic designs are epitomised by detailed fine-line imagery. The exquisite drawings were usually done on typical stirrup-spout pots, using red and white slips. The entire surface was covered with a white slip, then the illustrative designs were painted in red. ‘Ghostlines’—lines lightly applied to the base clay to sketch out the exact design—have been found on some pots. These were done when the pot was not completely dry, before the white slip was applied.1

The fine-line pottery of the Moche illustrates a wide range of subject matter, from domestic to religious. While the Moche had no written script, they left invaluable information about their culture in their fine-line drawings. On the surfaces of their pottery they seem to have drawn in detail every facet of their life. Not only does this make these ceramics fascinating today, but it also led to the fine-line vessels being highly prized by other cultures that flourished around the same time as the Moche. For example, Moche pottery has been discovered in Vicús tombs—it was far more refined than their locally produced ceramics.

The two stirrup-spout pots provide examples of different decorative content—geometric patterning and bird motifs—while the flared, or bell-shaped, bowl illustrates Moche fine-line design at its most complex. Two different anthropomorphic figures appear around the exterior of this pot. The Decapitator God (Ai Apaec) is shown facing the front, with his fanged mouth turned down in a menacing manner. Only the dead are usually shown in this frontal manner. In each hand he holds the accoutrements of his craft: a tumi blade with a serpent tail, and a severed head. The second figure is shown in profile, and his bent legs suggest that he is running. With his lined face, he may be a manifestation of the Decapitator God known as Wrinkle Face, identifiable by his distinctive snake belt. He also holds a tumi in one hand. Along with elaborate clothing and ornaments, feline symbols and snakes adorn both deities, demonstrating the sumptuous detail that the Moche were able to achieve with the fine-line technique. From bottom to scalloped-edged top—possibly originally in the form of the step pattern—the remaining exterior of the bowl is filled with representations of anemones and waves, symbols of power and authority. The step pattern also features in the headdress of the central figure. In this instance, the inside of the pot has been left plain, but on others the decoration continues into the interior.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Christopher B. Donnan, Ceramics of ancient Peru, Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, UCLA 1992, p. 69.

Moche ceramic designs are epitomised by detailed fine-line imagery. The exquisite drawings were usually done on typical stirrup-spout pots, using red and white slips. The entire surface was covered with a white slip, then the illustrative designs were painted in red. ‘Ghostlines’—lines lightly applied to the base clay to sketch out the exact design—have been found on some pots. These were done when the pot was not completely dry, before the white slip was applied.1

The fine-line pottery of the Moche illustrates a wide range of subject matter, from domestic to religious. While the Moche had no written script, they left invaluable information about their culture in their fine-line drawings. On the surfaces of their pottery they seem to have drawn in detail every facet of their life. Not only does this make these ceramics fascinating today, but it also led to the fine-line vessels being highly prized by other cultures that flourished around the same time as the Moche. For example, Moche pottery has been discovered in Vicús tombs—it was far more refined than their locally produced ceramics.

The two stirrup-spout pots provide examples of different decorative content—geometric patterning and bird motifs—while the flared, or bell-shaped, bowl illustrates Moche fine-line design at its most complex. Two different anthropomorphic figures appear around the exterior of this pot. The Decapitator God (Ai Apaec) is shown facing the front, with his fanged mouth turned down in a menacing manner. Only the dead are usually shown in this frontal manner. In each hand he holds the accoutrements of his craft: a tumi blade with a serpent tail, and a severed head. The second figure is shown in profile, and his bent legs suggest that he is running. With his lined face, he may be a manifestation of the Decapitator God known as Wrinkle Face, identifiable by his distinctive snake belt. He also holds a tumi in one hand. Along with elaborate clothing and ornaments, feline symbols and snakes adorn both deities, demonstrating the sumptuous detail that the Moche were able to achieve with the fine-line technique. From bottom to scalloped-edged top—possibly originally in the form of the step pattern—the remaining exterior of the bowl is filled with representations of anemones and waves, symbols of power and authority. The step pattern also features in the headdress of the central figure. In this instance, the inside of the pot has been left plain, but on others the decoration continues into the interior.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Christopher B. Donnan, Ceramics of ancient Peru, Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, UCLA 1992, p. 69.

Moche ceramic designs are epitomised by detailed fine-line imagery. The exquisite drawings were usually done on typical stirrup-spout pots, using red and white slips. The entire surface was covered with a white slip, then the illustrative designs were painted in red. ‘Ghostlines’—lines lightly applied to the base clay to sketch out the exact design—have been found on some pots. These were done when the pot was not completely dry, before the white slip was applied.1

The fine-line pottery of the Moche illustrates a wide range of subject matter, from domestic to religious. While the Moche had no written script, they left invaluable information about their culture in their fine-line drawings. On the surfaces of their pottery they seem to have drawn in detail every facet of their life. Not only does this make these ceramics fascinating today, but it also led to the fine-line vessels being highly prized by other cultures that flourished around the same time as the Moche. For example, Moche pottery has been discovered in Vicús tombs—it was far more refined than their locally produced ceramics.

The two stirrup-spout pots provide examples of different decorative content—geometric patterning and bird motifs—while the flared, or bell-shaped, bowl illustrates Moche fine-line design at its most complex. Two different anthropomorphic figures appear around the exterior of this pot. The Decapitator God (Ai Apaec) is shown facing the front, with his fanged mouth turned down in a menacing manner. Only the dead are usually shown in this frontal manner. In each hand he holds the accoutrements of his craft: a tumi blade with a serpent tail, and a severed head. The second figure is shown in profile, and his bent legs suggest that he is running. With his lined face, he may be a manifestation of the Decapitator God known as Wrinkle Face, identifiable by his distinctive snake belt. He also holds a tumi in one hand. Along with elaborate clothing and ornaments, feline symbols and snakes adorn both deities, demonstrating the sumptuous detail that the Moche were able to achieve with the fine-line technique. From bottom to scalloped-edged top—possibly originally in the form of the step pattern—the remaining exterior of the bowl is filled with representations of anemones and waves, symbols of power and authority. The step pattern also features in the headdress of the central figure. In this instance, the inside of the pot has been left plain, but on others the decoration continues into the interior.

Simeran Maxwell

1. Christopher B. Donnan, Ceramics of ancient Peru, Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, UCLA 1992, p. 69.