|

|

|

||||

|

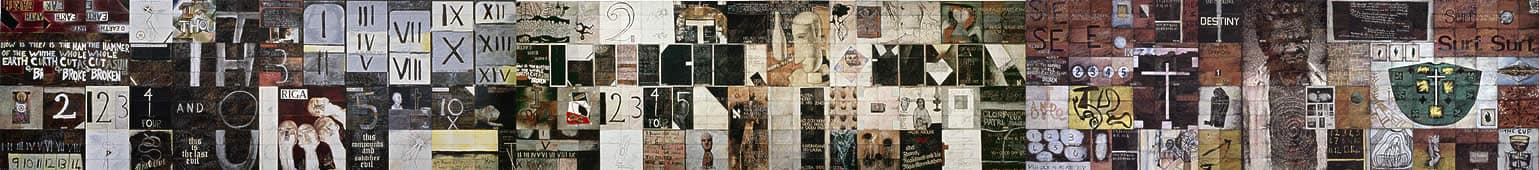

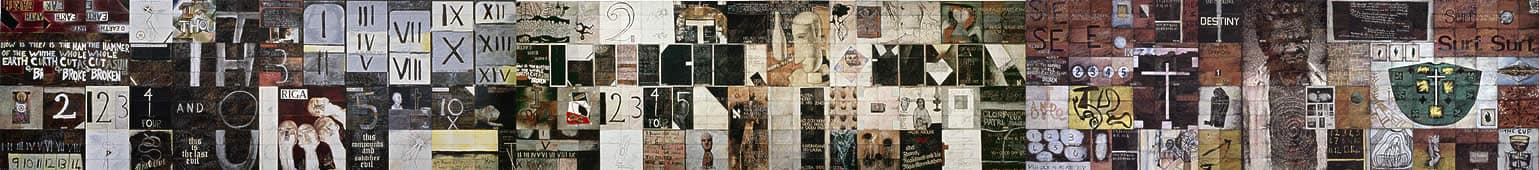

Bringing the periphery centre stage The more we look at his paintings, the more pervasive Tillers’s own presence becomes, not only through his very particular method of painting but also through constant references to the artist’s role and his shifting identity. Nicholas Baume1 By the time Imants Tillers was selected to represent Australia at the 42nd Venice Biennale in 1986, his work had received considerable national and international recognition. Betty Churcher, then chair of the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, wrote in the Biennale catalogue: [Tillers] represented Australia at the 13th Sao Paulo Bienal in 1975 and participated in the Kassel Documenta of 1982. He was recently represented in the successful exhibition, An Australian Accent, held in P.S.1, New York and since then has regularly exhibited with the Bess Cutler Gallery in New York. She noted that Tillers had collaborated closely with Kerry Crowley at the Yuill/Crowley Gallery in Sydney (his gallery representative at the time) to develop the Venice exhibition, in collaboration with Daniel Thomas, then Director of the initiating gallery, the Art Gallery of South Australia. Churcher concluded: ‘The major accolade … must go to the artist, Imants Tillers – we congratulate him for representing Australia so assuredly.’2 In 1986 the Australian pavilion had not yet been built in Venice and Tillers’ works were shown in the old Arsenale building. The works, which looked quite remarkable in this setting, included six major canvasboard paintings: Heart of the wood 1985, I am the door 1985, Mount Analogue 1985, Psychic (for Yves Klein) 1986, The Kondratiev wave 1986, and Thehyperborean and the speluncar 1986. After the relatively tentative beginnings of the early canvasboard works, the paintings shown in Venice revealed a marked confidence. They demonstrated the realisation of a vision that Tillers had been developing over the past few years towards an art in which provincialism, fragmentation and distance could be seen as highly productive material for an artist. He recognised that the tendency towards mimicry could be used to advantage, particularly when the source was itself the subject of transformation through the dotscreen matrix of reproductions disseminated around the world. In the Venetian context the works – reinvested with the aura of originals – that shone from the old walls within the cavernous space of the Arsenale were confronting for some viewers, and were also deeply intriguing in their painterliness, scale and sense of daring. Provincial or not provincial, the centres and the peripheries appeared as one. In the context of this study the focus is on those works that reveal transformations in relation to a deepening personal philosophical approach that would reverberate in his later work, and that provides the springboard for the discussion of related works. Although Tillers’ interest in cross-cultural issues would come to the fore in his Diaspora series in the following decade, these earlier works reveal that his preoccupation with the shifting nature of our personal and collective identities and displacements was apparent in the mid 1980s, as it had been from the beginning of the canvasboard system. Heart of the wood: the meeting place [Kiefer’s studio] is a metaphysical place where the artist attempts to understand complex ideas and themes and then integrate them into his physical surroundings. This place is the mind itself, at once malleable and steadfast, a filter through which concepts are pondered, invented, buried or transformed. Secret rites are performed there, and history is reordered; all is possible. Mark Rosenthal3 Tillers’ Heart of the wood and I am the door, both painted in 1985, drew directly on the work of contemporary German artists Anselm Kiefer and Sigmar Polke respectively. His interest in these artists and others, such as Georg Baselitz, can be related to the resurgence of neo-expressionist figurative painting in German art of the 1980s and his familial connections with Latvia as a northern extension of German-Baltic culture that informed his upbringing. Tillers had met Polke in São Paulo in 1975 and in the 1980s he became increasingly drawn to his direct quotation of images, his interest in the idea of being guided by higher beings and his playful sense of irony. Although his interest in Kiefer was less sustained, in 1985 Tillers was fascinated by Kiefer’s painting Germany’s spiritual heroes 1973, with its layered ambiguities of historical, social and personal identities. In his engagement with this painting Tillers found ways of interweaving the ambiguities of self with images and parables of the past. Despite his rapid rise to national and international attention the first canvasboard works, Suppressed imagery I 1981 and The field 1982, were quite tentative and experimental. The field comprises a large image traversing the grid of the canvasboards, like most of the works in the 1980s. Compared with the landmark exhibition The field at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1969, which focused on abstract painting and conveyed the strong impact of American art in Australia, Tillers’ painting The field could not have been more different. It depicts a couple of young Soviet schoolboys in uniform carrying satchels, in a field. In contrast to cool, hard-edge abstraction, Tillers enjoyed the naive, personal quality of the schoolbook image, enlarging and adding to it by working into the surface with his fingers. The do-it-yourself approach was important to him: ‘I identify with amateurs because they love what they are doing … I like the physicality of making art panel by panel at my table.’4 Tillers recalls that the imagery in The field came from his first alphabet book, which his mother disliked intensely due to its communist subtext. For him it held in memory the power and presence of one’s first books in life. With hindsight, the work represents the anomaly of the first-born offspring of migrant parents. While as a child he had identified with the boys who appear to be embarking on an adventure into the world at large, this has been filtered in adulthood through the lens of knowing, so that the idea of childhood enchantment is also a storybook mirage. The chimera of a past relayed through the experience of others and the shifting resonances of fantasy and reality is part of Tillers’ cultural inheritance that is inherent in many of his works from the 1980s. As Mary Eagle writes: ‘Between cultures there remains a realm of speculation. Neither is susceptible to explanation in terms of the other; and if they have been chosen for special uses, the bi-cultural experience becomes entangled with personal expression.’5 Tillers found that he could identify with the work of contemporary German artists who conveyed underlying anxieties in the wake of the Second World War and the recurring cycles of what Kiefer termed the terror of history. A counterpoint was at times apparent in the awareness of their country’s rich cultural inheritance, tempered by varying degrees of irony and a critical distancing. Tillers understood the complex issues surrounding identity from an Australian viewpoint and from his parents’ recollections of the war as teenagers. From both points of view there was an implicit struggle with collective guilt passed on to successive generations. As he said in 1987: part of my attraction to Kiefer was a similar response to the same cultural background. Latvia was consecutively under German and Russian occupation. Someone like Kiefer is exposing the guilt that the generation after the war experienced. I guess I’ve felt that too, at various times.6 Kiefer’s cavernous wooden room in Germany’s spiritual heroes was an imaginative adaptation of his studio space – a converted schoolhouse. In this reinvented space he inscribed the names of German artists and composers he admired, including Richard Wagner and Joseph Beuys. This hall of memories, inhabited by ghosts, is rendered precarious as the flames around the edges of the room threaten to engulf and destroy the past. Tillers’ adaptation of Kiefer’s painting in Heart of the wood, which he once described as a kind of self-portrait, is infused with irony and an empathic response. The wooden hall reminded him of Latvian theatre sets and he responded to the image as a theatre of the mind, reconstructing and adding to the image to discover more about its physical and metaphorical resonances from a personal point of view. In a bold move Tillers placed his name in the rafters; the blocky typeface surrounded by small figures and animals drawn from Latvian children’s storybooks. The idea of including an artist from the antipodes with Latvian ancestry into this pantheon corresponded with Tillers’ ambition to challenge established hierarchies by bringing the peripheries centre stage. It simultaneously sends up his own pretensions in the playful rendering of the letters surrounded by fairytale characters. Although this was clearly a provocative idea, the challenge was not antithetical to Kiefer’s own spirit of questioning. As Mark Rosenthal wrote: Kiefer’s attitude about a Germany whose spiritual heroes are in fact transitory and whose deeply felt ideals are vulnerable is not only ambivalent but also sharply biting and ironical. The title itself, taken from an elementary school text, is pedantic and ultimately comical. These great figures and their achievements are reduced to just names, recorded not in a marble edifice but in the attic of a rural schoolhouse … Certainly the future of Kiefer’s nation is not clearly stated in Germany’s Spiritual Heroes.7 While satire plays a part, so does a genuine recognition of the artists, composers and writers whose contributions endure beyond their passing. In Heart of the wood Tillers references a modernist still life by Margaret Preston: Western Australian gum blossom 1928, an allusion to his Australian identity as well as tribute to his wife, Jennifer Slatyer, who was at the time running an innovative business in Sydney, called Modern Wildflowers. In the work there are also allusions to German artists, such as Peter Bömmels and Baselitz. The figure to the right in a black-and-white vortex, based on Baselitz’s The poet 1965, appears to be struggling out of the wood while being consumed by flames. In a striking parallel with cultural debates in Australia, Baselitz was one of a number of artists who had been concerned by the way that much German art of the 1950s and 1960s had succumbed to the overpowering influence of American art, and feared a loss of their identity. On the other hand, Baselitz and Kiefer recognised the complexities of identity for artists like themselves, from a war-torn country. Tensions of the past relayed in the present were transmitted in Tillers’ Heart of the wood eliciting a range of responses, including a personal one by a New York critic who saw it in Venice. As Tillers recalled in 1987: His reaction was to say that his whole family, which was Jewish, had been wiped out in Latvia by the Germans. In the same year that Tillers’ work was shown at the Venice Biennale, the first significant show of contemporary German art to be seen in Australia was held at the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide. The exhibition, Wild visionary spectral: new German art, included many of the artists who interested Tillers, including Baselitz, Bömmels, Kiefer, Polke, Joseph Beuys, Jiri Georg Dokoupil and Jorg Immendorf. In his catalogue essay the exhibition curator, Ron Radford, noted: ‘Much of the world’s interest in recent German art has been focused on the New Painting and the painters’ related work in sculpture.’ He remarked that the art world had become bored with much conceptual and minimalist art, welcoming a return to figurative, painterly expression, ‘a direction in which the Germans appear to excel’.9 A number of these figurative artists were important to Tillers, providing him with insights into ways of engaging with complex issues surrounding identity and displacement that shaped his own art in the 1980s and beyond. A rendezvous with de Chirico Against a misty background of classical ruins, similar to those in the paintings from the 1920s, the head of the last horse painted by de Chirico stands out. But more than an animal, it is a mass of ruins and fragments of the past. Paolo Baldacci10 Tillers’ painting The hyperborean and the speluncar 1986, with its visual and poetic, evocative resonances of the sea, the wind and the cave, was a perfect work to be shown in the watery city of Venice. The hyperborean of the title refers to Greek mythology and the people who lived in a land beyond Boreas, the north wind, while the speluncar refers to one who explores caves. The dominant sources are de Chirico’s The mysterious animal 1975 and a painting by nineteenth-century British artist Frederick Leighton, Greek girls picking up pebbles by the sea 1871. In his work Tillers establishes a meeting place for artists of different timeframes and stylistic approaches, who adopted a similar approach to his own. In both instances these artists borrowed from classical Greek sources and adapted them to their own ends. Tillers has in turn edited the Leighton image for his own ends, extracting a single figure from the group of women, while still locating her on a beach. In keeping with the sensuality of the original, the woman is like a figure on a classical Greek vase come to life: poised in her tender gesture of collecting, and invested with a sense of drama in the folds of the drapery that wrap around her body and billow above her head. In the more direct quotation of the de Chirico image, classical references to houses, temples and acropolises are treated in the manner of sixteenth-century artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo, inhabiting the horse’s head that has become the mysterious, symbolic bearer of the past. This hybrid animal has also been described as a tribute to Friedrich Nietzsche, who invoked the idea in his text Thus spake Zarathustra that the human condition is continually returning to what has already been done in cycles of eternity.11 De Chirico noted that he was influenced by the ‘exceptional poetry’ in the writings of this much-discussed but greatly misunderstood thinker. In the spectrum of Tillers’ work de Chirico, unlike Leighton, has been a continuing source of fascination. Tillers was alerted to de Chirico in 1979 by novelist Murray Bail, when he presented him with a note written by the Japanese–American artist Shusaka Arakawa, who with Madeleine Gins ‘had met the ageing and much maligned painter in New York seven years earlier’.12 As Jennifer Slatyer has written, until the time of this introduction, a year after de Chirico’s death, Tillers was familiar with the much-reproduced, well-known images that this painter had produced between 1910 and 1919, but was quite unaware of the ‘strange and incongruous, but massive output of the remaining sixty years of his life’.13 The reason for this was partly that de Chirico’s work produced after 1920 had been reviled by his peers and many critics, and had not received much serious attention from public art museums until the 1980s. In the 1980s Tillers embarked on a rigorous study of de Chirico’s later works, completing nearly sixty paintings that referred to him, a number of which were shown in the exhibition A life of blank: works by Imants Tillers in Hobart at the Plimsoll Gallery, University of Tasmania, in 1992. Tillers felt strong affinities with aspects of de Chirico’s philosophical approach, including the idea that the early and later work needed to be seen as a whole, ‘as an expression of a way of being and thinking’.14 This corresponded with Tillers’ idea of the canvasboard paintings as one continuous work. Since the 1970s Tillers had been interested in metaphysical ideas and he was drawn to de Chirico’s belief in clairvoyance and his recognition of apparently coincidental occurrences across time and place. He identified with the idea of intuitively responding to correspondences across generations and different parts of the world. Tillers’ often ambiguous response to his own cultural inheritance also meant he could empathise with the conundrum of de Chirico’s hybrid identity: ‘his early Greek education, his Middle-European culture picked up in Munich and his French intellectualism (which so fascinated Apollinaire and later Cocteau)’. The reconciliation of difference for de Chirico was found in ‘an enigmatic and disquieting world waiting to be discovered at every street corner’.15 The idea of enigma was integral to de Chirico’s sense of self, revealed in some one hundred self-portraits. These often eccentric images are always linked to some other personage or an ‘eternal statue’. The face in de Chirico’s Self-portrait 1924 appears quite vulnerable, emerging from a statue as though he were part of this world and part of another reality beyond the one we see. In Tillers’ portrait A life of blank VI 1984 he appears to have morphed with the older artist. His expression is similarly enigmatic, as though in looking through the metaphorical lens of time he was compressing the past and present. He gazes out at the viewer with a wariness that could be seen as part of the shared experience for most artists emerging from the isolation of the studio and putting themselves on the line in full public view. This portrait simultaneously conveys a sense of mind, a contemplative awareness of presence and distance, and immediacy in the expressive touches and handprints that in turn suggest the multiple roles of the artist. Another quite personal connection is found in Tillers’ work Inherited absolute 1992, based on de Chirico’s The painter’s family 1926. The work includes an evocation of a drawing by his first-born daughter, Isidore, that she did when she was four years old. It is a bit like a school test or exercise, as the text on its side under her name indicates. It is also like a drawing of shapes before they have become codes. In the remaking of the work Tillers traced the formation of the letters of a child learning to write – learning, tentatively, how each letter is shaped – observing his offspring’s early interest in numbers and repetition. Isidore Tillers recalls that as a child she often spent time with her father in his studio at Mosman and, like her younger sister Saskia later on, she often had a go at making her own drawings or canvasboard works that her father collected. Occasionally her art would be exhibited in his shows and she felt excited by the inclusion of her work in his painting. As she says: Inherited absolute includes one of my earliest drawings that my dad kept and used later on. The painting was done a year after my sister, Saskia, had been born. It is a work to do with children and it was his way of responding to what was happening at the time.16 In Tillers’ adaptation of de Chirico’s painting the additional web of fragmentary lines across the surface suggests cyclical patterns of birth and the passing of time. The inclusion of the easel and painting stick in the background suggests a shared reliance on technical painting skills, although de Chirico’s attitude to tradition was ambiguous and often ironic.17 There To be really immortal, a work of art must go completely beyond the limits of the human: good sense and logic will be missing from it … In this way it will come close to the dream-state, and also to the mentality of children.18 Tillers was taken with de Chirico’s transcendence of good sense and logic, both in his art and his novel Hebdomeros. The book was recommended to Tillers by Murray Bail, who pointed out the bizarre fact that in its first paragraph there is a reference to Melbourne. In this ‘picaresque of the imagination’ the central character, Hebdomeros, sometimes supported by unidentified companions, goes in search of ‘what is presumably Eternal Truth, encountering strange situations on the way and philosophising about them in a dramatic if inconclusive manner’.19 The text begins: And then began the tour of that strange building situated in a street that looked forbidding, although it was distinguished and not gloomy. As seen from the street the building was reminiscent of a German consulate in Melbourne. Its ground floor was entirely taken up with large stores. Although it was neither Sunday nor a holiday, the stores were closed, endowing this part of the street with an air of tedium and melancholy, a certain desolation, that particular atmosphere which pervades Anglo-Saxon towns on Sundays.20 There is a parallel between the uncanny correspondences in de Chirico’s text and Tillers’ own earlier writing in a book titled Three facts, published in 1981.21 As Margaret Plant pointed out, ‘The beauty of chance is a major theme of Tillers’ book’.22 In his text Tillers refers to a conversation that is partly real and partly imaginary, between himself and Michael Scullion while on a journey in the Flinders Ranges National Park in South Australia. The philosophical conversation begins with a subject raised by German mathematician Kurt Gödel ‘of arithmetical propositions that were undecidable – that they were both True and False’. Not long after Tillers had embarked on his journey into the landscape on foot, he found that his goal seemed indeterminate. Looking on a map, he noted that the peaks which corresponded to his chosen mountain range were called Mount Hayward, South Mount Hayward, False Mount Hayward and Hayward’s Bluff. The campsite and his path lay in the shadow of a mountain that denied its own existence.23 Tillers notes the intriguing fact that the Great Wall of China appears in the Flinders Ranges. He also points out mistakes made by surveyors who ‘gave’ the Northern Territory part of Queensland. He relates such discrepancies in the real world with paradoxical ideas proposed by Duchamp, as well as the notion of mysterious ‘omnium’ – the fusion of all things – that overcomes the paradoxes of true and false.24 Plant noted that Tillers was a young artist of a philosophical bent not usual in Australia, whose interest resides in the relationships of images to the real thing, and images to images, that become exposés in seeing. ‘It is art about art – in itself not new in the twentieth century, but Tillers presents his findings with autobiographical verve.’25 The relationship in Tillers’ art with real and philosophical notions of mapping, mountaintops and mistaken identities expressed in Three facts, is reflected in the underlying ideas of three seminal landscapes that he painted in the 1980s: Mount Analogue 1985, Hiatus 1987 and Kangaroo blank 1988. Mount Analogue 1985 One of [René Daumal’s] most brilliant demonstrations, called ‘The Falsehood of Truth’, isolates error as the principle of creation and existence, for only one tiny truth would obliterate the entire universe by its wonder. This advanced cosmic sense of humour has no other name than [Alfred] Jarry’s term pataphysics. Roger Shattuck26 Tillers’ interest in various forms of mapping and mistaken or hypothetical identities can be related to one of his favourite books: René Daumal’s Mount Analogue. Daumal’s fabulist, pataphysical novel deals with the merging of fact and fiction, and was the basis for the title of Tillers’ best known mountaintop painting, Mount Analogue 1985. The text of this small, intricate novel begins when the narrator receives a letter from a reader of an article he had written on Mount Analogue. The reader, Father Pierre Sogol, believes that this mountain exists. He writes to the author of the article who is at first perplexed, considering that his text was not written with a specific place in mind but rather as a study of the symbolic significance of the mountain in ancient mythology, albeit with an alpinist’s passionate love of mountains. As the narrator elucidates: I had written in substance that in the mythic tradition the Mountain is the bond between Earth and Sky. Its solitary summit reaches the sphere of eternity, and its base spreads out in manifold foothills into the world of mortals. It is the way by which man can raise himself to the divine and by which the divine can reveal itself to man … In fact it was in Greek mythology that I found the symbol completed by the story of the revolt of the children of Earth who, with their terrestrial natures and terrestrial means, attempted to scale Olympus and enter Heaven on feet of clay … In China people have always referred to the ‘Mountains of the Blessed’.27 The narrator, who remains nameless, meets with Sogol and they proceed on the journey to the mountain. As Daumal wrote, On a subliminal level, Tillers may have been drawn to von Guérard’s image as a result of his own experiences visiting the region and walking in the Snowy Mountains since the 1970s. On another level, in the mid 1980s he had been mainly focusing on contemporary artists, such as Enzo Cucchi, Francesco Clemente, Kiefer and Polke, and quoting from this nineteenth-century image seemed like an anomaly at the time. Nevertheless, the inspiration of a Viennese-born, German-trained artist who lived and worked in the antipodes and who painted an aspect of the snowy environment in Australia little recognised overseas, provided a way for Tillers to bring an unexpected local reference to the Venice Biennale. In painting the work painstakingly panel by panel, he also found analogies in the way that small sections became aggregates of particular elements, such as the rocks that reminded him of conceptual work by artists like Mel Bochner or Richard Long, who used these natural materials in their installations. On a practical level, Tillers also recalls being struck at the time by the possibilities that the reproduction of the shiny cover of von Guérard’s publication offered for the new materials he had discovered, in particular metallic paints and oilstick. Once again, the low-tech aspects of the painting process were important to him. As he said: I discovered one could produce monumental images in quite modest circumstances … I have a water jar and two little plates, one for metallic colours and one for black, and then just the paints [and] a few rags … This work was done in my studio at home in Mosman, in a ten-foot by twelve-foot room. I just did it in sections. I didn’t actually ever see it in my studio because I couldn’t ever install it anywhere … This work is one of the first where I started using oilstick, which comes in tubes. It is a bit like using your fingers. It is very hard to get much detail. They get blunt very quickly … In painting his work Tillers dramatically enlarged the scale of von Guérard’s colonial image, creating a new work in its place. The new spatial orientation suggested different ways of reading the image that was paradoxically both further away and more present. When the work is installed there is a proximity to the landscape, creating the impression of being able to enter it. On the other hand, Tillers’ emphasis on the painterly surface, along with the canvasboard grid, moves the work further from von Guérard’s illusory reality. This push and pull between distance and proximity is heightened in the areas of the painting where parts of the image don’t quite meet up. Tillers has long enjoyed these disjunctures that reinforce errors in reproductions, adopting them as part of a fresh approach to ways of seeing in the transformational process of his canvasboard works. In the 1980s Tillers went on to paint other works inspired by von Guérard. Years later, when he moved with his family to Cooma – not far from the location of the subject of von Guérard’s North-east view from the northern top of Mount Kosciusko – he re-engaged with the landscape of the Snowy Mountains in his work. As he said in 2003, ‘While [Mount Analogue] was the anomaly in 1985, it has now become almost central to my practice … In a sense this work is an anticipation, a premonition of where I’ve ended up.’31 Hiatus 1987 Literary works encourage freedom of interpretation, because they offer us a discourse that has many layers of reading and place before us the ambiguities of language and of real life. Umberto Eco32 A couple of years after painting MountAnalogue Tillers undertook one of his most significant works: Hiatus 1987. This work brings together an image derived from Eugene von Guérard, based on a New Zealand landscape, with an impressive text-based image from Colin McCahon, painted almost a century later. In this way Tillers fused a nineteenth-century sense of the sublime with a contemporary conceptual approach that questioned issues of identity, faith and the human condition. Both sources are now in Australian collections: von Guérard’s Milford Sound with Pembroke Peak and Bower Falls on the west coast of Middle Island, New Zealand 1877–79 in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, and McCahon’s Victory over death 2 1970, a gift from the New Zealand Government to the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, in 1978. When Tillers first saw McCahon’s Victory over death 2 in the National Gallery of Australia he was struck by its overwhelming presence and landscape associations. In an interview with Jenny Harper, who curated an exhibition of Tillers’ work for the National Gallery of New Zealand in Wellington in 1989, he also noted his attraction to McCahon’s use of contemporary scale, the arte-povera painting surfaces he sometimes employs, the conceptual flavour of the numbers and words, the ‘radical hybridization of received styles and ideas’, and his use of biblical quotation that gives his work a simultaneously archaic and contemporary presence. He added: There is a constant tension between the search for meaning, the desire for transcendence and a pervasive, immovable skepticism. It is this aspect of McCahon that I find most interesting and most relevant to our condition today.33 As his interest in McCahon deepened Tillers felt that New Zealand art had been a blind spot, not only in the northern hemisphere but for many in Australia as well. He was taken with the idea of trans-Tasman interchange and the fact that von Guérard had travelled to New Zealand in 1876, when he visited Milford Sound and made the sketches upon which his painting was based. For Tillers, a striking visual correspondence between von Guérard’s and McCahon’s work is the way that the peaks of the letters in the later painting mirror the mountain peaks in the nineteenth-century landscape. In McCahon’s Victory over death 2 the words ‘I am’ are subtly reflected in the black shadow of ‘am I’ next to it. In the surrounding text McCahon explored the biblical account in John’s gospel (12:27–36) of events following the raising of Lazarus. He noted that the work belonging to his Practical religion series included what seemed like ‘a simple I AM at first. But not so simple really as doubts come in here too. I believe, but don’t believe.’34 In Tillers’ Hiatus the shadow area to the left of McCahon’s painting has been replaced with von Guérard’s Milford Sound landscape, which in turn becomes reinscribed with biblical references. There is a corresponding presence in the way these images have been construed, with the enormous scale of ‘I am’ set against the vastness of the landscape. The interpretation of ‘I am’ as the word of God can alternatively be seen as the artist’s own struggle to find a voice, to find meaning. Like the cry from the wilderness echoing around the still pool of Milford Sound between the mountain peaks, there is a sense of questioning, not only the idea of faith but of our human frailty, our existence and mortality, and the possibility of an afterlife. The surprising fact of simply being present in the world is suggested in a quotation in Tillers’ work, taken from Japanese artist On Kawara, in the lower right: ‘I am still alive’. As opposed to the expressionistic response to the spirit, Tillers identified with McCahon’s asceticism; on a philosophical level this relates to René Daumal’s ideas in his Mount Analogue text. As Roger Shattuck writes in the introduction, Daumal believed that in contrast to Henri Bergson’s surrender to the object of knowledge, it is important first to withdraw from the world into the arena of subjectivity as the initial stage of consciousness, which he described as an ‘asceticism’, before attempting the opposite and more tempting movement of fusion with all things. [Daumal] understood very early that the basic act of consciousness is a negation, a dissociation of the I from the exterior world of not-I. Meaningful perception reduces and refines the I, withdraws it from the world … Then, however, beginning a vibratory rhythm that must follow if self-annihilation is not to result, the pure consciousness expands again into all things, experiences the world subjectively once more, loses itself in the mystery of creation.35 Faced with the letters ‘I am’ in the work of McCahon and Tillers, the viewer is struck by the sheer physicality and architectural presence of the words. Do we identify with ‘I am’ in a self-reflexive process, or do we see ourselves through another, like Tillers might? Or do we simply enjoy the physicality of the word as image? All are possible. One aspect of the surrounding text that can be enjoyed is the sound of the words, their poetry that emerges from what was once an oral tradition. On another level, the words can be seen as symbolic. In Hiatus, for example, the letter I that stands between two worlds is like a beacon or a gap, a lacuna that suggests a pause between sounds. It is a space for contemplating new meanings in the work. This gap or beacon recurs in various forms in works that followed, including Kangaroo blank 1988. Finally, the combination of images from past and present in Hiatus also calls to mind a sense of place. New Zealand Kangaroo blank 1988 [I]s there anything of which one can say, Look this is New? The idea of a hiatus, a gap in space and in understanding, is central to Tillers’ painting Kangaroo blank 1988, commissioned for the bicentennial exhibition Creating Australia: 200 years of art 1788–1988. The inspiration for the painting was gleaned from A portrait of a Kongouro from New Holland, 1770, by George Stubbs, a work that Tillers came across in a 1962 publication of Joseph Banks’ Endeavour journal.39 Banks had travelled on the Endeavour with Captain Cook in 1770, and took botanical and other specimens with him back to England. Stubbs’ painting, a commission for Banks, was a long-distance affair, an imaginary reality – part fact, part fiction. He had never visited Australia and his image of a kangaroo, an odd creature from a far-flung foreign land, was based on a skin that had been taken back by Banks and perhaps ‘stuffed or inflated for its portrait session’. It is also possible that he referred to drawings by shipboard artist Sydney Parkinson.40 Various aspects of this work were eminently well suited to Tillers’ processes of transformation. As Nicholas Baume writes in an eloquent essay on this work: Stubbs’s painting is sweetly ironic for Tillers, an artist preoccupied with working from images he has seen only in reproduction. In Kangaroo the usual relation is inverted; instead of the Australian artist being frustrated by his isolation from the original overseas, in this instance the European artist was handicapped by his distance from Australia. In Tillers’ painting the central image of the kangaroo has been removed and replaced with a rectangular, dark void – an absence, a blank – that evokes the implied presence and disappearance of the animal. The concept of the ‘blank’ was informed by artist Shusaka Arakawa, as reflected later in inscriptions in Tillers’ paintings: ‘we have decided not to die’. Arakawa and Madeleine Gins had written Pour ne pas mourir and, as Jennifer Slatyer has noted, the book is ‘a dissertation on various notions of “blank” … “the atmosphere of blank” … “perceiving oneself as blank” and so on’.42 The metaphysical or unconscious dimension of these ideas is reinforced in Kangaroo blank by the inclusion of a beacon with luminous rays drawn from Arakawa’s work. As Baume wrote: An exploration of the ‘mechanism of meaning’ is Arakawa’s stated purpose, attempting to picture the mind’s unconscious thought-processes. Lending a different meaning to the word ‘blank’ Arakawa asks, ‘What is emitted point-blank at a moment of thought, anyway?’ Tillers’ layering of two contrasting images from utterly different contexts is something of a point-blank confrontation, a new thought emerging from a collision of types. Both Stubbs’s and Arakawa’s images are faintly absurd, the first because it suggests accuracy without first-hand observation, the second as it purports to visualize the immaterial – a moment of thought.43 Compared with the soft, billowing clouds and organic forms, and passages of dark and light of the natural landscape borrowed from Stubbs, the geometric precision of lines emanating from the Arakawa beacon suggests a purity of abstract thought. It is a way of making the invisible visible, like an alternative radiating light source or force-field connecting all things. Tillers was entranced by the beacons in Arakawa’s work and applied them repeatedly in his art. They appear in two other works painted in 1988: Quest: I the speaker and Satellite, in which the luminous beacon floats across an out-of-register image of the Basilica of St Francis at Assisi, alongside text-based works quoting Colin McCahon. The combination of elements reinforces a metaphysical dimension. Both works were included in Tillers’ exhibition One painting, cleaving at the Wollongong City Gallery in 1990, along with a series of works known as One painting 1980–84. By photographically documenting the underlayers of a work in the series, such as Two paintings, hidden from view 1982, before they were painted over, Tillers made the invisible visible. One photograph of a suppressed layer shows two Latvian schoolgirls ironing ribbons, like ghosts on either side of the Basilica of St Francis. The image of Latvian children has correlations with Tillers’ first canvasboard works, Suppressed imagery 1981 and Thefield 1982; it is as though they occupy the shadow world of the subconscious and of the past. In a catalogue essay for the One painting, cleaving show, Bernice Murphy wrote: Where one set of procedures aims at extruding, laying bare and demystifying the conventions of representation, exposing them as an objectifiable set of calculative propositions, another set of procedures in Tillers’ work reinstates invisibility and autobiographical traces, moving back in the direction of private meaning and symbol, from which the former set of procedures radically took their departure.44 In 1988 a survey of Tillers’ work from 1978 to 1988 was held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. The Exhibitions Director, Iwona Blazwick, noted in an overview that Tillers’ choice of images is not arbitrary or ironic. ‘The meaning of each fragment is carefully investigated and all its possibilities both celebrated and exploited. In this sense Tillers cannot be collapsed within the “appropriation” bracket which characterises so much postmodern practice through the 80s.’ She added to this point, noting the reinvestment of meaning and spirituality in the works.45 The difference in Tillers’ approach to much appropriation of the 1980s has also been elucidated by Graham Coulter-Smith in his in-depth study of the artist’s work some fourteen years later. In the catalogue essay accompanying the London survey, Michael Newman noted that for Tillers origin and place were dependent on dissemination and displacement. In relation to the canvasboard system, he made the analogy: ‘If the “death of the author” coincides with the birth of the reader, as [Roland] Barthes suggests, then the origin is replaced by a multiple and inclusive subjectivity.’46 The 1980s was an astonishingly intense and productive decade for Tillers. During this time he had developed increasing confidence in the possibilities of the canvasboard system, refining his technical approach and the processes of quotation and transformation. In these years Tillers consolidated his ideas in a number of series based on Georg Baselitz, Jackson Pollock, de Chirico, von Guérard and McCahon. His personal vision, informed by his bicultural background and the irresolution this implied, called for an alternative space and a web of connections that could contract and expand in varying degrees of concealment and revelation. During this time the national and international exposure of Tillers’ art was extraordinary, and by the end of the decade some critics and others in the art world felt that he had had his day in the sun and that his best period was behind him. After a brief hiatus in the wake of the intensity of the 1980s, however, Tillers embarked on a new body of work that consolidated much of what had come before, and opened out into the remarkable Diaspora series. Deborah Hart 1 Nicholas Baume, ‘Where truth is no stranger to fiction: Imants Tillers, Kangaroo blank 1988’, in Creating Australia, two hundred years of art: 1788–1988, exhibition catalogue, Adelaide: International Cultural Corporation of Australia Ltd and Art Gallery Board of South Australia, 1988, p. 227. |

| NGA Home | Introduction | Themes | Search | Essays | Learning | Visiting | Previous |