|

|

|

||||

|

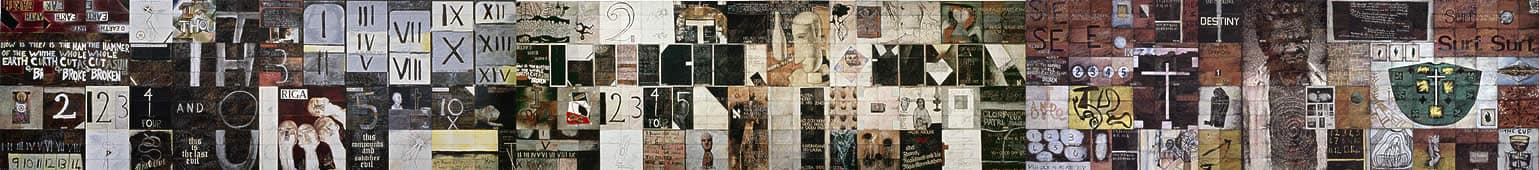

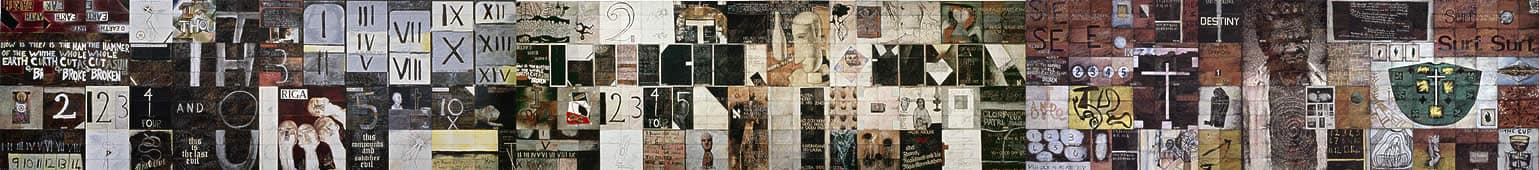

A work in progress Like a garden that is never finished, the work of an artist is forever in the process of becoming. ‘I am “I” who is becoming “I” who is not I’, writes Haniya Yutaka. Imants Tillers, Land beyond goodbye1 A group is standing in front of an Imants Tillers painting from his Nature speaks series at a small gathering attended by Corinne Mazzocchi-Mallarmé, the great-niece of French poet Stéphane Mallarmé. She is intrigued that her relative has been an important source of inspiration for a contemporary Australian artist and together they engage in a conversation about the references, both visual and textual, in the multi-panelled work. Inscribed around the edges is the quote: ‘A throw of the dice will never abolish chance’, from Mallarmé’s radical late poem Un coup de dés [A throw of the dice]. It appears with a range of sources, including traces of sublime cherubim from a drawing by nineteenth-century German Romantic artist Philipp Otto Runge, the colloquial Australian ‘no worries’, and allusions to the natural environment. In the course of the conversation Mme Mazzocchi-Mallarmé asks, ‘So tell me, Imants, which part of it is yours?’ He pauses for a moment, looking back at the work, and answers: ‘None of it.’ There is stunned silence followed by laughter. It is the typically disarming answer of an artist who is famously reticent and enigmatic. Some animated discussion ensues as the group looks more closely at the work. After a while she says, ‘Well I guess it is really all yours.’ The presence and absence of self is a conundrum at the heart of Tillers’ work. It is bound up with concerns about origins and originality, the interactions of self and other. It is a question implicit in his long-term strategy of appropriating images from reproductions of artworks and other sources, and re-working them. While issues of authorship may be challenging, Tillers’ work is easily recognisable. The personal aspects of his approach reside in his remarkable canvasboard system, which involves both a philosophical and practical approach, and in the specificity of his choices – be they visual, intellectual or intuitive. The personal aspects appear in the correspondences he discovers between the sources and his own experience, the unexpected juxtapositions and transformations that form new realities, the physical processes of making the works and their sensuous, layered surfaces, in the content and presence of the art. Tillers has never denied his sources; he has always acknowledged the visual excitement and potency of the work that inspires him. Yet the question presents itself as to why he has persisted with a method that involves, to some extent at least, an ambiguous self-erasure or distancing. There are no simple answers, but there are intriguing possibilities. This approach can in part be traced to his artistic background of ‘post-object art’ in the 1970s and to the dematerialisation of both the traditional art object and the role of the artist. There is also the benefit of distance to gain clarity, as well as the liberating potential of what TS Eliot referred to as ‘impersonality’ (drawing upon a Buddhist tradition): the seemingly paradoxical dissolution of the self in order to find the self. To look in the mirror and see the face of another looking back provides an alternative viewpoint, as in Tillers’ A life of blank IV 1984, where the portrait of Giorgio de Chirico stands in for the enigmatic ‘self’. This approach can be seen as a protection from the overt expression of emotions and as a point of identification, relevant to and beyond the self, flowing into a web of wider connections. Close consideration of his art in the context of the times and the artist’s personal experience reveals Tillers’ ongoing, and at times oblique, interest in questions of identity and displacement, highlighting the subtle, complex interweaving of subjectivity and objectivity. Although born in Australia, Tillers’ experience growing up as a child of Latvian refugees who migrated from a displaced persons camp in Hamelin, Germany, in 1949, left him with a sense of fragmentation and an awareness of psychic exile. The feeling of his own ‘in-betweenness’ – belonging partly to two cultures and not fully to either – has informed the need to find connections outside of the self. It is as though an ascetic distancing through others is at times a foil for what he once described as the ‘self as a site of conflict’. The counterpart to inner conflict is the artist’s intense intellectual and visual curiosity, his ongoing metaphysical questioning and openness to chance, and his interest in a multi-disciplinary, flexible responsiveness to the world. Considering the intense curiosity that is obviously at the core of Tillers’ art over the years, it will probably seem remarkable to many people that he is not one for computers and that he doesn’t use the internet. Since the early 1970s print media has been Tillers’ main way of receiving information, of finding images and setting up a rendezvous between artists – including, of course, himself – in his work. A feeling of the context of the times in which Tillers came to prominence is apparent in Daniel Thomas’s catalogue introduction for the exhibition An Australian accent:three artists – Mike Parr, Imants Tillers, Ken Unsworth at PS1 in New York, in 1984, curated by John Kaldor. Thomas wrote: Until the 1950s Australians and New Zealanders believed they lived at the End of the World though since jet aircraft and television they have discovered the Global Village. Even at the End of the World, literature, the one art form which was readily portable, was indeed available in highest quality to all who desired it. The book trade was efficient and high-minded; the education system reached the remotest outback … Dante … Proust and Freud might come your way growing up on a farm, though not until you settled in town might you find Artaud, Robbe-Grillet, Levi-Strauss, Chomsky or Foucault. But even in the bush, art information landed regularly with the art magazines … Art International had a market in Australia in the 1960s and in turn ran an amount of Australian material; Artforum and Art in America are still read … we are now also reading Flash Art and other European magazines. The Italians have shown the healthiest curiosity about us and we now read about ourselves there as well in magazines of our own.2 One of the main aspects of Tillers’ approach has been to make an advantage of a perceived disadvantage of distance by using second-hand imagery, adapting images from reproductions, not original works. This has provided an easier way to work from the isolation of his studio while remaining in touch with the wider world. It is linked with ideas about ‘the original’ and the proliferation of reproductions in books, journals, newspapers, magazines, posters and postcards. It also provides the necessary distance from the original. In the process of reproducing works colour, scale, surface texture and resolution often change. Add to this the quite surprising fact that the sourced images are often small so that the transformations are generally much greater than one might imagine. The idea of transformation and interaction between the sources used and Tillers’ own ways of perceiving the world is part of the rationale for the selection of works discussed in this text. The focus is not on ‘merely fashionable’ sources or appropriations of single works with little mediation. The emphasis in this context is rather on those works that reveal more personal connections with Tillers’ life and philosophical approach, and also on the hybrid works combining several sources, setting up multiple possibilities for interpretation and contemplation. These works provide insights into the artist’s wide-ranging interests, including art, philosophy, literature, history, society, politics, physics, ecology and metaphysics. In addition to this ‘geography of mind’ is his interest in the geography of place and in symbolic journeys – as in Mount Analogue 1985 and Hiatus 1987 – that flows through to his most recent work. These aspects form part of the portrait of an artist who cherishes the fact that ‘the self’, like art and life itself, is continuously open to interpretation – mutable, never fully understandable and always in a state of becoming. The book, the stack, the field, the web Tillers has written that the life of an artist is essentially a solitary one, yet the world he inhabits in the work itself is connected with a rich repository of ideas and imagery. The idea of one and many, of the unit and the multiple, and of an interconnecting web-like whole, relates to the distinctive and remarkable system that Tillers has developed for his art. Since 1981 this has involved working on small amateur painters’ canvasboards that come together in a flexible, grid-like structure to form a work. A single work can contain anywhere from 3 to 300 panels. This method has provided a way for the artist to work in relatively small studios and still create large paintings, even though he has often not been able to view an entire work until it is exhibited in a larger gallery space. After coming up with the initial idea and creating a working ‘map’ as a guide, the making of a painting is quite intimate; the artist sitting at his studio desk to work on individual panels that subsequently get placed on the floor as one layer after another is left to dry. The process of work evolving from table to floor is performative, mirroring the subsequent installation of the work on the wall as one panel is applied after the next, like a Fluxus Aktion in which actions are reiterated and reversed – ‘Element 1 moves up to Element 2’ – like components of an evolving puzzle gradually expanding from the parts to the whole. After being shown on the wall (held on by Velcro tabs), the canvasboards come apart again, stacked in beacon-like formations that have a sculptural presence. In some instances the stacks have become works in their own right. The movement from the stack to the wall and back into the stack again suggests a cyclical metamorphosis from one state into another. It reveals the fluid, dynamic interaction in Tillers’ art between intimacy and expanse, movement and stillness, permanence and impermanence. Over the years Tillers has accumulated a vast library that has moved and grown with him. After four-and-a-half decades in Sydney, his home for the past decade has been in Cooma, in regional New South Wales, where he lives with his wife Jennifer Slatyer and their daughter Saskia (their older daughter, Isidore, having moved back to Sydney to attend the Conservatorium of Music). Tillers’ books can be found stacked in his studio. Some are organised on the shelves in groupings, others pile up on the furniture and the floor. At the opposite end of the room, around a cupboard and door, dense stacks of canvasboards cluster together. Some are stacks of finished paintings, the delicate, abstract patterns of the coloured edges hinting at the hidden ‘secrets’ contained within; others are stacks of works in progress. The cumulative presence of these stacks containing the past and waiting for the future reflects one of the most significant aspects of Tillers’ system: of the boards unfolding from one work to another, to form an encompassing whole, variously referred to as the Book of Power, the Canvasboard System, One Painting and the Large Image Field. Each of these descriptors conveys pertinent aspects of Tillers’ approach: of the art as an ongoing book of potent signs, as a holistic system that is non-linear and cyclical, and as bringing forth one continuous work comprising a vast field of diverse images and visions. The idea for the Book of Power, also the title for the first major monograph on the artist by Wystan Curnow, was inspired by Stéphane Mallarmé, as Tillers explains: The idea comes from the French poet Mallarmé who wrote in 1895: ‘Everything, in the world, exists to end up in a book’. The panels have been numbered right from the start and the panel count is continuous.3 From the start, each canvasboard has been numbered and more than two decades later the count is approaching 80 000 boards. In Tillers’ mind the boards are to be numbered from one to infinity, a rationally impossible dream. On one hand the notion of the Book of Power and of numbering suggests a linear reading. Yet it is also possible to see the Book itself as regenerative and cyclical in the processes it employs. It is worth remembering in this regard that the pages of Mallarmé’s Le Livre were to be unbound and read in any order, and that the placement of words on the pages of his poem A throw of the dice was quite unorthodox and spatially daring. When Paul Valéry received Mallarmé’s manuscript of this poem he wrote: ‘It seemed to me that I was looking at the form and pattern of a thought, placed for the first time in infinite space’.4 Although there is an inevitable linearity in the consecutive numbering process of the canvasboard system, when we think of the breadth of infinity this idea dissolves. Again, it has been pointed out that Mallarmé wrote of ‘eternal circumstances’, when strictly speaking ‘circumstances belong to time rather than eternity’. Yet the fascination resides precisely in that intersection.5 The idea of Tillers’ system, which is malleable, expansive and ephemeral, involving a performative dimension in the construction and deconstruction of a work each time it is installed and dismantled, is an approach that had its origins in the experimental environment of the visual arts of the 1970s. The idea of the canvasboard system as an evolving, holistic system that literally goes beyond the frame has been shown, by Graham Coulter-Smith, to extend back to Tillers’ formative art practice and philosophical enquiries.6 The 1970s were a time of intense questioning, of environmental and earth art, performance art, minimalism, and conceptual art. Tillers entered into this milieu with a questioning spirit, but not before he had resolved some issues of familial expectation. Tillers’ father had been averse to his son becoming an artist and to keep the peace the young Tillers decided on the more acceptable path of architecture at the University of Sydney. It wasn’t long, however, before he renewed his interest in the art debates and avant-garde events of the time. The most notable of these events was his involvement in the wrapping of the Little Bay coastline in Sydney with Christo and Jeanne-Claude in 1968–69, when ‘the then young architecture student was first gripped by a feeling for the immense, wonderful power contained in works of art’.7 A couple of years after Wrapped Coast, Little Bay Tillers was working on a thesis, entitled ‘The beginner’s guide to oil painting’, as a partial requirement for his Bachelor of Science degree. It was an ironic, even playful title that aimed to consider ‘a new conceptual framework’ using a multi-disciplinary approach that took into account the relationships of recent art with physics and environmental issues. He was also interested in alternative models to the role of the artist as sole creator of an original object, including the possibilities of the artist being the conduit for ideas, images and actions through a systematic approach. As Ann Stephen writes: Tillers was one of the young Australian artists and writers who were receptive to the challenges posed by the first wave of Conceptual art. Tillers was writing an architectural thesis … concerned with the shift in the role of the artists from the producer of data to the amplifier … of systems rather than objects.8 The relevance of Tillers’ early writings to his canvasboard system in later years is the adaptation of the ideas underlying systems theory as ‘guiding metaphors’ for what might be possible in art. For example, in his thesis Tillers expressed interest in the writings of Ludwig von Bertalanffy, who proposed an ‘open system view’ as opposed to a mechanistic one: ‘the mechanistic view resolved happenings into linear causal chains, whereas the open systems view is based on principles of multivariable interaction (for example, reaction kinetics, fluxes and forces in irreversible thermodynamics) and a dynamic expansion of physical laws in light of biological laws’.9 Some three-and-a-half decades later Tillers notes that his interest in this field has been ongoing, recommending Fritjof Capra’s The web of life, published in 1996, as an important source that takes up many of the central ideas in his thesis to do with a holistic ecological approach. The new science of ecology that emerged in the 1970s enriched systems thinking by introducing the idea of communities and networks. This is implicit in Capra’s ‘web of life’ in which interdependent networks nest within other networks (an idea not unlike the multiple, small panels that would come to ‘nest’ in Tillers’ Diaspora series in the 1990s). Tillers’ idea for his canvasboard system model, which is a continuous whole, a network of diverse and multiple parts capable of endless flow, is in accord with the idea of ecological systems. His multidisciplinary approach as a student reflected developments in the late 1960s, when ideas about interdependent systems had crystallised, leading to the establishment of interdisciplinary groups. As Capra writes, around this same time the ‘atmospheric chemist James Lovelock had an illuminating insight that led him to formulate a model that is perhaps the most surprising and most beautiful expression of self-organization’ – the idea that the planet earth as a whole is a living, self-organising system.10 Tillers noted at the time that this holistic model ‘helps to reinforce the reverence for living which seems lost’.11 This was akin to the response of those astronauts who first travelled to the moon; the images sent back of the earth as ‘a blue and white globe floating in the darkness of space’, invoking both a sense of profundity and ‘the most powerful symbol for the global ecological movement’.12 The installation, the conversation, the reminiscence Tillers’ interest in alternative frameworks for painting can be seen in three works from the 1970s that provide significant insights into what was to follow: the installation of Conversations with the bride 1974–75; the series of collaborative etchings with George Baldessin, According to des Esseintes 1976; and the personal recollection of a visit to his parental country of origin, Reminiscences of a journey to Latvia 1978. Tillers’ preoccupation with ecology and with a system in which the microcosm and macrocosm are in a dynamic balance relates to the challenge he proposed to established notions of the centre and the periphery in the art world. The most fascinating early work in this regard is his installation Conversations with the bride, created for the São Paulo Bienal. The work comprises 112 postcard-size paintings: meticulously painted variations of images, predominantly by Marcel Duchamp and Hans Heysen. Each small painting has a chrome-plated reflective back and is set on a stand; all 112 stands inter-connect like a three-dimensional reflection of the canvasboard system that emerged in the following decade. The coalescing and overlapping images drawn from Duchamp’s The large glass 1915–23 and Heysen’s watercolour Summer 1909, along with painted images of the stands in Tillers’ installation flowing through many of them, conveys the simultaneity of multiple viewpoints. Through the images and reflections Tillers sets up intricate interactions between Duchamp, the archetypal European avant-garde artist who with intellectual rigour and playful humour challenged the limitations of the conventional art object, and Heysen, the archetypal traditional painter of the regional Australian landscape and the ubiquitous gum tree, which he brought to new light in his own time. This combination of elements reveals Tillers’ ability to look at international art while at the same time being regionally or provincially located. His use of multiple reflections also introduces the idea of conveying an apprehension of the fourth dimension13, as though in the rendezvous of elements across time and place, chance correspondences and coincidences are able to arise. In dialogue with Duchamp, Tillers creates a flexible organisational model that suggests the dematerialisation of the singular art object without negating the possibility of painting as a viable option. The idea of applying the postcard format and alternative materials also signalled his interest in amateur artists’ canvasboards later on. In these respects Tillers’ work finds parallels with the conceptual thinking of the late Ian Burn, who he met in 1972. Among Burn’s interests was the idea of calling into question the barriers between so-called amateur and professional artists, and rethinking the landscape. As he wrote: The idea of landscape does not just invoke rival institutional discourses, but today attracts wider and more urgent reflections. A commitment to representing the landscape has become about the ‘loss’ of landscape in the twentieth century … that is about its necessity and impossibility at the same time. Seeing a landscape means focusing on a picture, implicating language in our seeing of the landscape.14 Another ‘conversation’ was taken up between Tillers and George Baldessin. They were the two Australian artists selected for the São Paulo Bienal in 1975 and met again in Paris the following year. Tillers and Jennifer Slatyer had recently married, and they spent six months in Paris at the Cité Internationale des Arts. As Wystan Curnow notes, Baldessin – who was ten years older than Tillers and associated with Melbourne artists such as Fred Williams, Roger Kemp and Jan Senbergs – broadened Tillers’ horizons beyond that of his Sydney conceptualist milieu. ‘In exchange for an introduction to the technique of etching, Tillers infected Baldessin with his enthusiasm for Duchamp. Often they shared their routines, with mornings at the Cité print workshop followed by visits to museums and sightseeing in the afternoons.’15 Tillers made his first prints with Baldessin’s assistance in Paris and the two artists subsequently did a collaborative work. Tillers and Slatyer went to Vence, in the south of France, for a three-month residency after Paris, and it was during this time that he and Baldessin engaged in a lively correspondence back and forth to create According to des Esseintes. Baldessin would create his work on an etching plate and mail it to Tillers for him to add his part, and Tillers would start another plate that Baldessin would finish. Each finished print included the etchings from the two plates that each of the artists had started. In the final stages, Baldessin travelled to a print workshop in Nice where he met up with Tillers to refine and complete the works. Although Tillers generally prefers to work in isolation, he has done other collaborative works, for example, with John Nixon, John Young, Marianne Baillieu and Michael Jagamara Nelson. In the course of their time in Europe, Tillers and Slatyer visited Latvia. It was Tillers’ first visit to his parents’ original homeland; he was twenty-six years of age. Two years later he documented the visit in a work, Reminiscences of a journey to Latvia, inspired by a film that he had seen by chance in Paris: Reminiscences of a journey to Lithuania, by Lithuanian-born film-maker and writer Jonas Mekas. This connection with his Baltic ancestry conveys a personal dimension to cross-cultural concerns that would run through his later work, with the example of Mekas providing an important touchstone. Mekas, who grew up in a small farming village in Lithuania, had been arrested with his brother by the Nazis in the Second World War and was sent to a forced labour camp in Hamburg. They escaped in 1945 and hid on a farm near the Danish border until after the war, when they lived in a series of displaced persons camps. With the Soviet annexation of the Baltic States after the war they were forced to leave their homeland for New York, where they arrived in 1949. Reminiscence of a journey to Lithuania was made in 1971–72, when Mekas travelled back to Lithuania for the first time since he had left. ‘I’m a displaced person on my way home in search for my home, retracing bits of the past, looking for some recognisable places of my past,’ he says in a voiceover. As Genevieve Yue, who has written extensively on his work, recounts: Instead of filming the changes that had occurred, he attended to what had remained the same: his mother’s earthen stove, and the fields and woods that surround his home. In his notes in his diary he writes, ‘you don’t see how Lithuania is today: you see it only through the memories of a Displaced Person back home for the first time in twenty years’.16 Tillers was readily able to grasp Mekas’s dilemma from his own parents’ memories that were passed on to him. His mother and father had met when they were both twenty-one years old and living in a displaced persons camp in Hamelin, Germany, having left their Latvian homeland when the Soviet Union took control from the Germans. When they arrived in Australia in 1949 they struggled to come to terms with the loss of past connections that had shaped them. Author David Malouf (who initially discussed the concept of diaspora with Tillers) has written evocatively about this migrant experience, using the metaphor of heart and body ‘living in separation from one another’. This was especially true of Eastern Europeans whose homelands were annihilated. Malouf writes: These cultures were doubly displaced. By being cut off from their origins they did not go on developing as things naturally do, but were stopped at the moment of departure and kept as monuments to how things were. This is what gives them pathos. And in the new place they stayed alive and growing in the minds of a new generation, who had grown up in a new place, and with another language, only by response and change. This uneasy relationship between the wish to preserve and the willingness, if what you care for is to remain alive, to adapt and change, constitutes the deepest paradox of all – but one that touches on what is essential to the nature of things, and essential as well to our own human nature. What is carried back is not what is brought away.17 When he was growing up, the young Imants Tillers was an Australian out in the world and a Latvian at home. As the first-born child he was inculcated with the ‘Baltic idea’, with the history of the recurring struggles of the Balts under successive regimes, including their heartfelt struggle to retain their language and cultural traditions. As well as going to school during the week, Tillers attended Latvian school each Saturday, where he studied subjects such as Latvian geography and history in the Latvian language. This continued until he was seventeen, when he was one of only three students to graduate from the course. It was around this time that the intensity and weight of the responsibility to maintain his ‘Latvianness’ became too much, and for a while he rebelled. By the time he visited Latvia in 1976, Tillers was at a point where he felt curious again, and a bit more detached. He also felt moved by Mekas’s film and the significance of his search for the signposts of memory, evoked as much by glimpses of what is present as by what is absent from the screen.18 This was made more poignant because at the time of Tillers’ visit neither of his parents had returned to their original homeland, which was still under Soviet rule, since their departure thirty years before. He recalled that in Latvia he was ‘a kind of de facto visitor’, a surrogate for his parents, visiting their old haunts and their now aged relatives and friends. As he wrote: My response to going back to Latvia, a country I thought I was already familiar with even though I had never been there before, was in a sense pre-figured and intensified by Mekas’s film. I now have vivid memories of visiting the ramshackle farmhouse at Salaspils (an area that was out of bounds to tourists) where my father grew up, virtually next door to the site of a former Nazi concentration camp. In its place now stood a desolate monument to those who died there. Also, there is the intense memory of drinking cold, fermented birch sap with the family of my mother’s childhood friend Astra at their country vegetable plot.19 The other side of this was a feeling of detachment and the sense that the memories of Latvia that had been passed on from his parents – of beautiful lakes and forests – ‘were but phantoms’. He was also aware of an environment of tension in which people were not able to speak freely, ‘of a pervasive underlying anxiety with all our hosts – the need to be careful about what was said and where one went. One felt under surveillance all the time and there were constant signs wherever one went that this was an occupied country.’20 A recurring image in Tillers’ Reminiscences of a journey to Latvia is a blurry, evocative photograph of him with his father’s stepmother, her friend and a dog, taken by Slatyer. Each of the panels includes this photograph, progressively enlarged until distinct parts are out of frame, and set on large envelopes, emphasising the idea of fragmentary correspondences. On other envelopes are colour images of Lenin instructing the people, and miniature reproductions of iconic Australian paintings by Hans Heysen and George Lambert on postage stamps around the edges. The clarity of the Soviet and Australian images contrasts with the imprints in the successive panels around a Baltic forest, concealing a human presence. The ambivalence and camouflage of the figure in the forest is approached with a lightness of touch and wry, self-deprecating humour. Simultaneously, the shadowy blurriness of the successively cropped photograph itself suggests a state of being on the edge of disappearance. Tillers’ father never went back to Latvia and his mother only returned once, in 1982, with her daughter Maija. The complexities of the history of their homeland had become too difficult to deal with, complicated by the successive waves of colonisation over centuries and their own confusion as teenagers caught up in the welter of the Second World War. It was all too hard to revisit: on the one hand too traumatic and on the other too close to a nostalgic idyll. Cross-cultural dialogues In tandem with the indelible imprint of his familial Baltic origins that informed some of Tillers’ most significant works, in the 1980s he was evolving his ideas in relation to a centre–periphery debate sparked by Terry Smith in an article titled ‘The provincialism problem’, which suggested that in an international context Australian artists would struggle to be taken seriously as equals. ‘The cultural transmission is one way … the most a provincial artist can aspire to is to be considered second-rate.’21 Tillers took up the challenge, asserting (rather optimistically some would still say) that Australian artists like their Latvian counterparts could reverse expectations, not so much by trying to make the peripheries the centres but rather by establishing a more level playing field of cross-cultural exchange. Postmodern arguments flowing out of the 1970s and into the 1980s were against nationalistic agendas and one-dimensional views of the landscape, as well as opposing the overt personal expression of modernist abstraction. These debates occurred at the same time as contemporary Aboriginal art opened to a wide audience, such as the work coming out of the central desert in Papunya, which was deeply connected with place and country. For an artist like Tillers, who was keenly interested in the circulation of images from one place to another and who was intent on focusing on some of the most powerful art being created in different parts of the world, the remarkable paintings of artists like Michael Jagamara Nelson suggested fresh possibilities for reasserting the significance of artists from what was perceived as the margins. In the early 1980s Tillers was interested in moving beyond the idea that local art necessarily reflects local conditions in favour of wider correspondences. In substantiation of his approach he adopted the metaphor of Bell’s theorem to convey the connectedness of phenomena – shared experiences, images, ideas – in different places.22 He also drew upon the writings of Giorgio de Chirico and the idea of surprising synergies across time and place in those uncanny deja vu moments, and the recurrence of a shared Zeitgeist. In one of his most-quoted articles, Tillers provocatively claimed: locality fails. Perhaps the problem was not that locality was failing, but rather that non-Indigenous artists like Tillers were in part still grappling with a sense of belonging at the same time as trying to come to terms with Indigenous art, where locality clearly does matter. There was also the fact that much of the populace, including many Indigenous artists, lives in cities – contrary to stereotypic views of Australians abroad. As Daniel Thomas wrote, partly for a New York audience: ‘Australia has long been more urbanized than the United States … Artists seldom work in the bush … they are more inclined to stay at home, work, read, visit art exhibitions and plan their overseas travel’.23 However, an option that seemed to be missing from Tillers’ argument until later on was that local concerns need not be in opposition to the idea of coincidences across places and timeframes, but that the two could coexist. Where the idea of distance is interesting is that it creates space for reflection and for acknowledging difference. One of the ironies of the debates about his engagement with Aboriginal art is that Tillers was taking a stand against the view underpinning a number of exhibitions at the time: that non-Indigenous artists could become ‘more Aboriginal’. Although this was part of the evolving dialogue, he didn’t agree with the myth of primitivism or that non-Indigenous artists could ‘return to fundamentals’, taking issue with the view that by ‘the power and simplicity which is inherent in totemic objects, archetypal images and tribal rituals … the artist hopes will cut through the habits of contemporary sophisticated forms of communication’.24 Tillers saw these expressions as nuances of Aboriginality rather than engaging more directly with the contemporary work and difficult issues. As he wrote: The reluctance for a more explicit identification … for an authentic ‘cultural convergence’ can in part be explained by the deep guilt underlying Australian culture. For the history of white settlement in Australia in relation to the Aborigines is a story of homicide, rape, the forcible abduction of children from their parents and the methodical dispossession of the lands upon which their well-being, self-respect and survival have depended.25 Tillers’ ironically titled painting White Aborigines I 1983 does not reveal some neat idea of cultural convergence. Rather it depicts two non-Indigenous figures combusting in a landscape: one man with horns has part of his head blowing off, while his companion is similarly torn apart. In 1983 the work was written about by Paul Taylor – founder of the art journal Art & Text, and an influential art writer and commentator – when it was shown at Matt’s Gallery in London. Taylor’s text evades overt or hidden meanings in the work; he may have intended, characteristically, to be deliberately provocative: Insofar as its two large figures seem to be dancing as they are being blown apart, they can be called performers of the painting. They dominate the picture while inside them other figures pose and scramble; beneath them lies another, overpainted, image and below them is an obscure German text. This juxtaposition is not purposeful but is oriented towards good design.26 Surely one might consider more simple ways to achieve ‘good design’. On the surface there are some playful aspects to the painting. The figures were inspired by German cartoonist Wilhelm Busch, as was the figure in Spirit of place 1983. Yet there is a violent edge in these images, akin to those in parables or fairytales. In Spirit of place Tillers was clearly trying to find ways of thinking about place beyond a conventional western landscape tradition. His sources for the work include Latvian images from storybooks, traceries from Papunya Tula painting, and echoes of Ian Fairweather, delicately veiled and layered across the surface (remarkably without brushes, instead using his hands). The main running figure reminded Tillers of his father, although he also becomes a more generic protagonist who seems to be literally trying to find a way into the picture. The nexus of Australian, Latvian and German imagery has been a recurring feature in Tillers’ work over the years, suggesting multiple readings and transformations. In an interview with Tillers, Paul Foss quoted Nena Dimitrijevic, who wrote in Alice in culturescapes that appropriation ‘is only justifiable when it serves to establish a new signifying system’. In response to Foss’s question about transformation in his work, Tillers noted: It’s not something you deliberately set out to do. I think that art has to proceed from its own basis and from one’s own feelings and subjective reactions to things. Only if art achieves some sort of power can it have a transformational role.27 It was Tillers’ work The nine shots 1985 (p. 86) that caused the most heated debate when it was reproduced in the catalogue for the 1986 Sydney Biennale, curated by Nick Waterlow. Ironically, the work itself was not exhibited – the work that was shown was Lost, lost, lost 1985 (the title of another Mekas film). In The nine shots the figure of a shambolic, dislocated figure from a work by German artist Georg Baselitz is set within a field of carefully worked fragments from a very beautiful, complex painting by Aboriginal artist Michael Jagamara Nelson. As Howard Morphy has written, it elicited a powerful response from artist Gordon Bennett in his The nine ricochets 1990, which also included an appropriation from Tillers’ work Pataphysical man 1984, inspired by Latvian artist Janis Jaunsudrabins. In time much has been written about these two works, to the point where they often become identified with each other in peoples’ minds. A long-distance communication later occurred when the two artists were invited to collaborate for Commitments, organised by the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane, in 1993.28 Tillers’ component comprised a painting inspired by de Chirico’s work Greetings of a distant friend 1916. It was an image that he believes came to him telepathically from Bennett at 1.30 pm on 27 July 1993. Not surprisingly, Bennett was sceptical, although he noted in a fax to Tillers that he had been driving through the central desert at the time. For the show Bennett contributed an installation that included in its parts their faxed correspondence, an appropriation of Tillers’ stack of canvasboards and adaptations of the de Chirico–inspired work. In their correspondence he also made reference to the earlier The nine ricochets and the image of the Latvian figure in Tillers’ Pataphysical man that he had appropriated, noting that he had kept it close to him for many years, for use at the right time: I was very excited to find this small gnostic symbol of a snake nailed to a cross revealed to me (in your work), during the painting process situated precisely where I wanted it! … Maybe there is something in mental telepathy after all.29 In the 1980s Tillers found the experience of the heated debate around the connections with Indigenous art in his work difficult. He believed that he was often misconstrued or misquoted, that he was finding his way, haltingly maybe, but still attempting to find a way for dialogue to happen. He felt the danger of the debate becoming trapped in time, as well as a reluctance to engage in too much self-exposure. For a while he went silent. In 1988 Tillers welcomed the opportunity to have The nine shots included in a landmark exhibition that would show the work in a wider context, A changing relationship: Aboriginal themes in Australian art 1938–1988, curated by Dinah Dysart and Catherine De Lorenzo at the SH Ervin Gallery. Although the painting was already well known through reproduction, this was the first time it had been exhibited in Australia. He also agreed to show in a very large exhibition, Balance at the Queensland Art Gallery, curated by Michael Eather in collaboration with Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities and artists. Eather recalls that when Tillers accepted the invitation to exhibit, many other artists were immediately keen to be part of it. The catalogue introduction outlines some of the complexities in putting the show together: Shared influences have long been in existence in this continent. Australia has a tradition of adapting and improvising. Australian Aboriginal and Islander people themselves developed strong trade routes of which some continue to be used today … In recent years, many artists have welcomed and embraced a wider range of outside influences and incorporated them into their own art. … Uncertainty towards the validity of artists demonstrating ‘shared’ influences is felt by many. Acknowledging junction points in our existence can be associated with fears of violation and severance. Others simply deplore any blendings whatsoever, but should artists be denied these opportunities? Throughout the 1980s both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal artists have had much cause to re-think their ways of working. The 1980s revealed a huge escalation of political and social awareness and acknowledgment of Aboriginal culture.30 It was Eather who, more than ten years later, facilitated a one-to-one dialogue between Tillers and Michael Jagamara Nelson that resulted in an ongoing body of work. As a senior artist of considerable talent and insight, Jagamara has participated willingly and of his own accord, sharing some knowledge and discovering new possibilities for his own work in the process. The deepening expression of Tillers’ interest in cross-cultural issues occurred in the 1990s with his major Diaspora series (discussed in Chapter 2). Although this series was sparked by the liberation of the Baltic States, it reflected wider cyclical patterns of displacement than those of his familial past. These paintings include significantly more sources than his previous work, reinforcing the idea of cross-cultural meeting places. Following the completion of the series Tillers sought a deeper engagement with locality. This coincided with his move to Cooma where he found space, literally and metaphorically, to reconsider his philosophical position. It was in the expansive Monaro region of parched summers and winter snow that he began to find ways of reconciling aspects of his split identity between his familial past and his present, reflected in his article ‘When locality prevails’.31 In the broad spectrum of Tillers’ cross-cultural dialogues, developments in his work over the past two decades are not so much about taking an optimistic, progressive view, as responding to the potentially regressive climate that Paul Feyerabend wrote about in his book Farewell to reason (also the title of one of Tillers’ Diaspora paintings) that refers in part to the diaspora or displacement of Indigenous people from their tribal lands. Feyerabend noted that in terms of a vision, western civilisation is threatened by monotony and dullness, by an advancing fog of sameness. He reflects on the fact that cultural diversity and cultural change is beneficial, ‘while uniformity reduces our joys and our (intellectual, emotional, material) resources’.32 Chance encounters Thinking through some of the personal dimensions of Tillers’ work, the question that comes to mind is whether it is possible to be enigmatic and passionate at the same time. The answer becomes apparent through a source that has been one of the most important to him over many years: Giorgio de Chirico. A master of enigma and chance encounter, de Chirico was an appropriator ahead of his time who was obsessive in his passions and who reworked many of his own paintings, finding coincidences and correspondences in unexpected ways, making intuitive leaps beyond the visible to the invisible. An interest in things metaphysical is another thread woven through Tillers’ work – not in terms of a belief in an omnipotent figurehead but rather in relation to the possibilities of the mind and consciousness, and the interconnections between all things. This is related to his interest in physics and ecology, and also to an awareness of the mystical that cannot be easily articulated. Among the many tomes in Tillers’ studio is a small book by René Daumal, a French author who died at the age of thirty-six, titled Mount Analogue. This text, written towards the end of Daumal’s life, revolves around a journey to a mountain that begins as a mythical proposition and ends up being a real place. The text conveys the many pathways of the journey, none of them straightforward. Daumal, who had studied Sanskrit, was part of a group in Paris known as the Simplists, who sought to go beyond the surrealists in their investigations of the absurdist possibilities and mysteries of human consciousness. In the novel the main characters are passionate, obsessive gatherers and cataloguers of data (philosophical, scientific, geographical, meteorological and so on). There are uncanny parallels with aspects of Tillers’ interdisciplinary curiosity when the narrator, on a visit to Pierre Sogol, the other main protagonist of the novel, notes: Along the path, glued to the window panes or hung on the bushes … hundreds of little placards were displayed. Each one carried a drawing, a photograph, or an inscription, and the whole constituted a veritable encyclopaedia of what we call human knowledge. A diagram of a plant cell, Mendeleev’s periodic table of the elements … a cross-section of the human heart, Lorentz’s transformations formulae … logistic equations, phonetic charts of the sounds employed in all languages, maps, genealogies – everything in short which would fill the brain of a twentieth-century Pico della Mirandola.33 In the process of the accumulation of diverse kinds of knowledge the main protagonists realise that no matter how much you know it is never possible to know it all; that we need to keep on questioning, we need to retain a sense of awe and reverence for the sheer mystery of living that is not lessened but actually increased by gathering different kinds of knowledge. Daumal’s Mount Analogue has much in common with Tillers’ philosophical approach. It is a bit like the obsessive, rational and irrational aspects of the canvasboard system, where a journey takes us into a labyrinth of the visible and invisible simultaneously. Like Tillers’ system that unfolds, enfolds, and folds back into itself again, only to re-emerge once more as the opportunity for interaction arises, Daumal suggests regenerative ways of being and becoming. He never finished his novel. In fact, he stopped in the middle of a sentence in the fifth chapter. As his wife, Vera Daumal, noted: ‘His politeness would not allow him to keep the visitor waiting who knocked on the door that day in April 1944. It was the last on which he held a pen.’34 Yet, in a sense it is fitting that there is no fixed conclusion. As with Tillers’ Book of Power, Daumal believed that it was possible to suspend the limitations of rational impossibility and move in our minds towards infinite possibility. There are genealogies across a spectrum of Tillers’ interests that reinforce the idea of embracing limitless possibilities of the nonsensical and the procreative potential of chance encounters, from René Daumal to Stéphane Mallarmé, and Giorgio de Chirico to Marcel Duchamp, to mention a few. It was Duchamp who said, almost as an afterthought, that ‘apparently, the artist acts as a mediumistic being that forges a path from the labyrinth beyond the realm of space and time to a clearing’.35 For an artist like Tillers, with a strong grasp of conceptual art and an early fascination with Duchamp, it was a bold decision to continue with painting. Duchamp, who had been a significant impetus for Tillers’ work Conversations with the bride, challenged the idea of the traditional art object supplanting the idea with his readymades – such as his famous urinal, Fountain 1917, signed R Mutt. He saw art as an intellectual rather than an aesthetic challenge, putting forward the notion that painting was over. By contrast, from the 1980s onwards Tillers’ commitment to painting never wavered. Yet he was equally committed to challenging fixed boundaries – quite literally going beyond the frame in his dynamic canvasboard system. As his ever-expanding library suggests, Tillers shares something of Duchamp’s intellectual curiosity, extending beyond art to physics and metaphysics, science and a sense of the absurd. In Tillers’ studio his canvasboard stacks echo his books in stacks, encompassing ‘hidden’ information that comes to life with each installation or reading. In this regard there is another connection with Duchamp that suggests a surprising, metaphorical correspondence with Tillers’ art, to do with the painting Tu m’ 1918 that provides a fitting postscript to this introduction. Although Duchamp only did a few paintings after 1912, when he swore off conventional painting categorically, Tu m’ was a notable exception. It was a commission for his patron Katherine Dreier, and was to be situated above the bookshelves in her New York apartment. In his painting Duchamp included many references to his earlier works – the bicycle wheel and the corkscrew, for example – describing it as ‘a kind of resumé’ in which everyday objects are transformed into paintings as shadow structures.36 There is an uncanny connection with Tillers’ canvasboards in Duchamp’s painting – in the multiplicity of squares or rhombuses, inspired by a sample book for paints that appears to have found associative links with the multi-coloured spines of the books on his patron’s shelves. In relation to Tillers’ canvasboard system, it is as though Duchamp, being the conjurer that he was, has taken the idea of the stacks of canvasboards in the studio, and made the potential energy of them kinetic, propelling them into space, with the little sign-writer’s hand pointing the way. It is as though this sign might even turn the other way, like when those mischievous souls turn road signs in reverse while the rest of us are asleep, to create an alternative direction, another reading of the puzzle, the conundrum of the labyrinth, that is endlessly engaging in its content while forever retaining the enigma of possibility. Deborah Hart 1 Imants Tillers, Imants Tillers: land beyond goodbye, exhibition catalogue, Sydney: Sherman Galleries, 2005, n.p. |

| NGA Home | Introduction | Themes | Search | Essays | Learning | Visiting | Previous |