|

|

|

||||

|

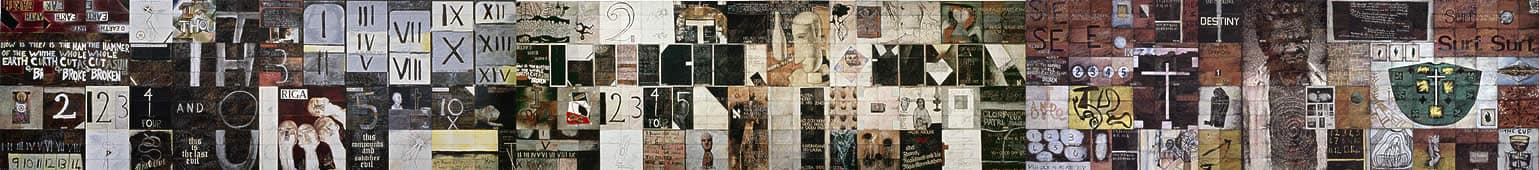

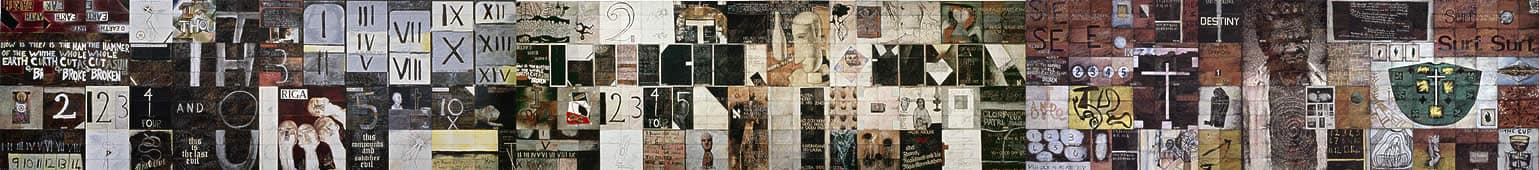

The Diaspora series: journey to new beginnings diaspora: a dispersion, as of a people of common national origin or beliefs Imants Tillers described his Diaspora series of the 1990s as introducing ‘a new paradigm’ in his work. The four major paintings in the series collectively represent an epic statement relating to diasporas – to the dislocation of peoples from their original homelands, including within their own lands due to colonisation, and the coming together of disparate cultures that is so much part of the stories and legacies of communities in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. For people in countries like Australia and New Zealand it could be said that the condition Seen collectively the Diaspora works are, to quote Pierre Restany, like a vast ‘epigraphic fresco’ enfolding many visions.1 Taking into account the broad sweep of the series from the first painting, Diaspora 1992, through Izkliede The diverse interactions across the four works create the impression of worlds within worlds, moving in multiple directions within each work and from one to another. They set up patterns, like visual mind-maps or sites of memory: of departures and arrivals, of cycles of rupture and regathering, of cataclysmic events and the intimate touchstones of everyday life. A distinctive element of these paintings is that they include more textual references than Tillers’ previous work, locating language as a potent source of identity: suppressed, fractured, regained and reworked as poetry, political activism, performance art, ritual, prayer and lament. All four works relate to his ongoing interest in overturning perceived ideas about the centre and periphery: of Europe and North America on the one hand and No-one, Balt or non-Balt, who witnessed the great pro-independence demonstrations of 1988–91 will forget them or the tremendous emotional impact they had: the songs, the tears, the sense of relief as people were able to say in public things which for fifty years they had been scared even to whisper in private; ‘For ye shall know the truth, and the truth will make you free.’ Anatol Lievin22 Tillers’ monumental painting Diaspora 1992 was in part a response to the dramatic political events in 1990 in Latvia, his parents’ original home country. While his sense of connection with Latvia was ambiguous, his awareness of an inherited culture and the spectres of the past were constants in his upbringing. As much as he may have felt some ambivalence as he moved from his parental home into the wider world, at times wanting to free himself from the shadows of a past he could only imagine, as a child of refugees his sense of responsibility to his parents’ memories was a constant undertow of his psyche. For his parents, time cast a long shadow; the trauma they had experienced leaving families, friends and homeland, had a profound impact on them, and in turn on their children – particularly their first-born child, Imants. After growing up with his parents’ view that the fate of Latvians was to be perpetually subsumed by a colonising culture or to go into exile in Siberia, the newfound freedom of the Baltic States that occurred with the collapse of the Soviet Union seemed to Tillers to be a remarkable, sudden turnaround. The reality was rather more gradual, more volatile and unpredictable. As Anatol Lieven writes in The Baltic revolution: ‘To many Western observers (and indeed to Gorbachev himself), the Baltic independence movements appeared to spring from nowhere. They were however preceded and accompanied by pro-independence groups stemming from the Baltic dissident movements.’3 Tillers had become aware of these dissident groups in 1989 when he saw footage of the remarkable staging of the Baltic Way, instigated in part by the future president of Lithuania, Vytautas Landsbergis, who was also a Fluxus artist.4 (It is hard to imagine a political leader of any persuasion in the West being not only an activist intellectual, but also a contemporary performance artist, musicologist and conceptual poet.) The extraordinary act of solidarity and defiance of the Baltic Way is inscribed by Tillers in Diaspora, in ‘Spatial poem no. 10’. The event is well described by Lieven: The speed of the independence process was due partly to the sheer size of the nationalist demonstrations and their cumulative effect in undermining the will of the Communist rulers. Most striking of all was the ‘Baltic Way’ of 23 August 1989, when two million Balts (two-fifths of the entire native population of the region) formed a continuous 370 mile chain from Vilnius through Riga to Tallinn to demand independence.5 Prior to independence, Tillers participated in an exhibition of international Latvian artists at the National Museum of Art in Riga and in the making of a film I am Latvian, in support of the pro-independence movement. It was only following independence, however, that he accepted the offer from the National Museum for a solo exhibition of his work. His visit to Riga in 1991 to make preparations for the exhibition (held two years later) meant a reassessment of his thinking: While there, I had to adjust my thoughts to the new political, social and economic realities, and also the constraints of the exhibition venue. So instead of attempting a survey of my paintings of the last twenty years, I decided to produce a new work for this specific venue, which would somehow reflect the present cataclysmic historical moment and also be a kind of summation of the concerns of my art up to the present.6 Tillers’ painting Diaspora represented distinctive shifts in his work, directly informed by the nature of the exhibiting venue in Riga. As Wystan Curnow notes: ‘The museum, unchanged since it was built in 1905, had a very attractive ambience – tall windows, high decorated ceilings, red marble columns – but its partitioned spaces which had been designed for small easel paintings were hardly suitable for presenting contemporary art.’7 The restricted wall spaces resulted in a new concept for a major work that could be broken down into a series of small paintings to be displayed individually in Riga, and later regroup as a composite whole. Tillers noted that the variable states of the canvasboard system as a whole had never been ‘so consciously extended as in this work’, in that component paintings could now be extracted or cut from the larger fabric of his One Painting concept.8 The first small painting that Tillers included in Diaspora 1992 was inspired by The Madonna Oriflamma 1926, by Nicholas Roerich, a Russian artist inspired by Tibetan mysticism, theosophy and Russian icons. He was also the originator of the Roerich Peace Pact, signed by President Franklin D Roosevelt and other world leaders in 1935, that sought the protection and preservation of cultural institutions around the world in times of war.9 The flag held by the Madonna in the painting is the Banner of Peace, the symbol of the Pact. Roerich, whose father was born in Latvia, had a special place in the hearts of many Latvians. Tillers’ interest in him had been longstanding. As he said: I have been interested and aware of Roerich’s work since 1979, when I was introduced to his paintings of mountaintops by a friend. This was just prior to my first trip to New York where I consequently sought out the well-hidden Roerich Museum on 107th Street. So it was with great excitement that I noted an entire room devoted to his mystical Tibetan landscapes at the National Museum of Art in Riga… in 1991.10 Fittingly, the Dalai Lama was among the first to see Tillers’ painting when it was first shown in The living mandala, an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, in 1992, organised in his honour. It is also fitting that this work, with its symbolic references to mysticism and pacifist aspiration, was the first component to enter the network of Diaspora. As Marketta Seppälä noted, Diaspora includes many references – images, fragments of images, words and symbols – from more than twenty works of art by eleven artists, from different art historical periods and from different cultures.11 Pierre Restany added: ‘The spectator witnesses an unfolding of coded messages and secret references, imprecations and fragments of ex-votos, making up the flux, or rather the weave of collective memory.’12 The trauma of shared memory is alluded to in the section containing four pale heads on long, flexible necks, probing space like radars, inspired by Georg Baselitz’s Oberon 1963–64 and re-inscribed with the word ‘Riga’, the red and white reflecting the colours of the Latvian flag. This segment relates to two earlier works by Tillers entitled A painting that does not speak I 1989 and A painting that does not speak II 1990, referring to the suppression of the Latvian language under Soviet annexation and the consequent loss of a public voice. Other references to the Baltic struggle to preserve their cultural identity are apparent in the Latvian inscriptions, including ‘May God give us your sign’ above two strange, mystical, linear figures by Bernhard Blume (one with a cross on the back of his head, the other cradling a cross on his shoulder). Another inscribed fragment is taken from a famous Latvian poem, ‘God your land is burning’, written when the symbolic centre of Riga, St Peter’s Church, was burnt in 1941. The idea of trying to find a voice for the times appears in Tillers’ ongoing interest in Joseph Beuys. One of the aims of Fluxus was to attain the spirit of collectivism, a view shared by Beuys, who had interested Tillers since the 1970s. The legend of Beuys, regarded by many as one of the great postwar German artists, is that he had been a fighter pilot in the Luftwaffe when his plane was shot down over the Russian front, resulting in his rescue by the Tartars who cared for him by rubbing his body with animal fat and wrapping him in felt blankets. While this may be part truth and part fiction, it was a potent redemptive symbol replayed in Beuys’s art time and again. By the 1990s Tillers had become interested in Beuys’s Manresa Action, performed in the Schmela Gallery in In Manresa, he created a fully delineated cross, filling in a halved cross with a dotted line … Beuys’s resolved cross was replete with potential content taken from situations in daily existence: for instance, a coalition of political parties, that is, a third way surpassing the division between Communism and Capitalism, or attaining spiritual wholeness, whereby the alienated condition that Beuys perceived to be inherent in contemporary Western life was healed. Even Beuys’s Theory of Sculpture is based on an Element 1 – Element 2 situation, wherein ‘movement’ produces the possibility of synthesis of the poles, yielding Element 3.15 The poetic Beuys invocation ‘Manresa, I fly to you’ is linked in Diaspora with a reference to Colin McCahon’s painting The shining cuckoo 1974. McCahon had been a key source in many works by Tillers, and in the Diaspora series his voice and vision is pivotal. His work incorporating biblical text and numerals suggests the passage of time as continuous and cyclical. In all four paintings in the Diaspora series the following words appear: ‘Earth o earth/How is the hammer of the whole earth cut assunder & broken’. Another echo across the four paintings appears in quotes from McCahon’s Rocks in the sky series 1976 that relate to the Stations of the Cross and Christ’s journey to Calvary. Curnow elaborates on Tillers’ special interest in McCahon’s use of numbers, ‘rendering most of the significant works featuring them’ and reminding us of the significance of counting in the Book of Power. Counting produces a regular rhythm, a beat. The more we come to know the Book, the more likely we are to pick up the rhythm, to hear … the beat of its heart … Pushing on, the count may appear fast or slow, according to output. Or the size of the work may seem to slow us up; for a while we are held in thrall by the expansive field of the image, the subliminal count will go on and on, steadily gathering together all that time of its making into one place. In front of Paradiso or Drift of Destiny we will be aware of that time.16 In Diaspora expansive and intimate gestures coincide. For instance, there is a personal reference in the painted number 5 to a card Tillers’ daughter Isidore had made for a cousin. On the other hand, numerals referring to the Stations of the Cross that appear in the lower left and the upper right are akin to markings on an ancient tabernacle and are like floating symbols over sky and land, the expanse amplified in the spatial configuration of sixty canvasboard panels. The echoes of the land recall Murray Bail’s observations that McCahon’s depth of feeling for his local landscape was written ‘literally onto the landscape’.17 Another interwoven element is the recognition of a lyrical Maori voice, reflected in the inscription from The shining cuckoo, Te tangi o te pipiwhara tangirau hotere, which had been translated by McCahon. The Song of the shining cuckoo. The ideas evoked by the phrase ‘pierce us and join us together’ has parallels with the physical and metaphorical nature of the Diaspora series, of multiple wounds and the search for unity. Travelling across Tillers’ painting is like a stretch through darkness – counting, pacing, alighting, moving up and down – across to the panels of light at the other end; to The shining cuckoo, and down to the little figure who seems to have connected with the light, the touch of Tillers’ hand connecting with the tender hand of Blume. This curious, even gently humorous image of finding a sign appears alongside a small McCahon landscape of ‘the pure land’, with a continuous horizon and luminous, pale yellow sky. Across the Diaspora series McCahon provides the antipodean counterpart to the visionary Beuys–Baselitz nexus. Here Tillers as an artist and curator of the content within his own work brings the so-called periphery into full view. This corresponds with the aims of Rudi Fuchs when, as director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, he agreed to host a large exhibition of McCahon’s work. Fuchs wrote that at times a ‘second-rate German or American artist is much more famous than a first-rate one from New Zealand’ and that when a country ‘is geographically as far removed from the traditional “centres” as is New Zealand, the problem is magnified’. He explained further: We were convinced that McCahon as an inventor and visionary should be seen on the same level as artists such as Jackson Pollock, Asger Jorn or Joseph Beuys. If we could bring about such a change, the history of modern art would be richer, more varied and interesting than it is even now.19 French writer and critic Pierre Restany recognised the aim of shifting the focus towards a more inclusive approach, noting in his essay ‘The Baltic idea’ that in Tillers’ imagination ‘McCahon joins the great Beuys-Fluxus-Baselitz Germanic line of redemption’. He recognised Tillers’ own painting as another link in a chain of interconnections, concluding with great passion: ‘I think of Diaspora from the top of the earth, and this effect of elevation significantly confirms the breadth of the enterprise, its ambition and success. Imants Tillers has perhaps accomplished the masterpiece of his career.20 Izkliede 1994 Let the big countries fight. Lithuania is small. Throughout our entire history the big powers have been marching over our heads. If you resist or aren’t careful – you’ll be ground to dust between the wheels of East and West. The only thing we can do, we, the small ones, is try to survive, somehow … You created this civilization, these boundaries, and these wars, and I neither can nor want to understand you and your wars. Jonas Mekas21 Tillers had the idea for a second work in the Diaspora series while he was installing Diaspora 1992 for his exhibition in Riga, Latvia, in 1993. This work, initially created with an Australian audience in mind, became Izkliede 1994 (Latvian for diaspora). As in Diaspora, the painting comprises multiple small images and includes Colin McCahon and Joseph Beuys as prevalent sources. Tillers was aware of Beuys’s interest in theosophy and the art of Wassily Kandinsky. Many artists, including Jean Arp, Hugo Ball and the Zurich Dadaists, had recognised Kandinsky as ‘one of the forebears of the new artistic movement’. They were inspired by Kandinsky and Pablo Picasso, not as painters, ‘but priests; not craftsmen, but creators of new worlds and new paradises’.22 A Kandinsky-inspired image appears in the upper left-hand corner of Tillers’ Izkliede, sourced from the cover of Kandinsky’s publication titled Sounds, which illustrated one of fifty-six woodcuts in the initial edition, published in Munich in 1912. The black-and-white image depicts a cluster of figures without identifying features, like disembodied souls that stand as a metaphor for the diasporic condition of people in flight into exile. There are parallels between Tillers’ and Kandinsky’s work processes, in their ‘transformational urge’ – the continual interchange of appearance and dissolution.23 There is also a shared spirit of experimentation. Kandinsky noted that as an artist his interest in writing was often regarded with consternation: ‘In the past, the painter was looked at askance when he wrote – even if it were letters. He was practically expected to eat with a brush rather than with a fork.’24 The inclusion of text in the Diaspora series is expanded in Izkliede, in hand-painted words and hand-cut stencilled lettering in an array of fonts across the surface, like a litany of symbolic resonances and incantations in different languages. The idea of language residing between the comfort of knowing, the void of not understanding and confusion of misunderstandings, is inherent in migrations across cultures. In Izkliede language functions in all of these ways. On one level it is about being open to the sounds and rhythms of words, while on another the unravelling of the code can lead to deeper meaning. For non-Latvian speakers, the idea of an encoded meaning appears in the delicate tracery of the words of the famous poem God your land is burning (also referenced in Diaspora 1992), interspersed with the Lord’s Prayer in Latvian, which overlays Carlo Carra’s mysterious The drunken gentleman 1916: DIEVS TAVA ZEME DEG! CIEMI UN PILSETAS GRUVEVOS NICIBAS PUTEKLOS TRIEKTAS [God your land is burning/villages and towns in ruins, blown away like particles This idea of repetition and the interweaving of elements continues in the upper right of Izkliede, where Tillers has transcribed Beuys’s text for the Manresa Action in full, in the traceries of stencilled words that run like subtle incantations down the work. It was 8 p.m. as the voice [Beuys’s] from the tape recorder announced: The idea of elements moving up and down in Fluxus performances had parallels with Tillers’ processes of making and installing his canvasboard works. It also suggested a world beyond the purely functional and rational aspects of reality – as Rudolf Steiner has described it, ‘what is essential is the fact that the visualisation liberates the soul from dependence on the physical’.27 Tillers noted that the Manresa Action is one of the few Beuys Actions where the text was transcribed, and that he was drawn to the open-ended, poetic and spiritual connections: These actions reveal the mystical and spiritual aspects of Beuys and his relationship to Steiner. There is a resonance between the McCahon texts and Beuys, the Latvian text and [Nicholas] Roerich’s theosophy. Many of these references are looking at Christian texts and beliefs in relation to extensions of those beliefs. There is also a sense of the spiritual yearning of the outsider.28 The idea of an other-worldly presence comes through in diverse, often surprising ways: in the large, watchful, surreal eye from Giorgio de Chirico’s painting Greetings of a distant friend 1916 and the abstracted, modernist angel in the top right, based on an amateur artist’s work that Tillers found in an op-shop. There is also a winged figure relating to a work titled Ascension to Mt Analogue 1960 by Remedios Varo, a surrealist artist who was born in Spain and lived in Mexico. Tillers was excited to discover that Varo had been inspired, as he had been, by René Daumal’s book Mount Analogue. An angelic presence of a more earthy kind appears in the maternal embrace of the child borrowed from an early religious painting by McCahon, The Virgin and the Child compared 1948. One of the later McCahon works, the multi-panelled The second gate series 1962, is a key source running through the second layer of Izkliede, alongside the black-and-white panel with a small inscription: ‘Is it nothing to you, ye that pass by?’ In The second gate series McCahon strove to find ways to communicate his ideas and feelings about current events and the ‘human situation’ with his audience. ‘In particular, the increasing antagonism of the Cold War adversaries, and the very real fear and possibility of nuclear war, troubled McCahon. Like many concerned New Zealanders at that time, he actively participated in protests such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.29 To address such political issues, McCahon felt that abstract shapes and colours were insufficient. As he noted in a letter to John Caselberg in August 1961, he would now need to use words: I am becoming involved with an idea for a large-scale statement on Nuclear warfare … The new series goes under the general title of ‘Gate’ by which I mean a way through. What I want with this screen is a way through also … In spite of a message which can burn I intend a painting in no way expressionistic but with a slowly emerging order. You probably know what I mean as you have done it.30 McCahon’s painting quoted various sources, principally the Old Testament books of Jeremiah, Isaiah and Lamentations. The idea of a work that is capable of burning with a slow, emerging order appears literally in Tillers’ Izkliede, in the evocations of charred walls that are inspired by Yves Klein’s Fire paintings. Mystical and alchemical theories had guided Klein as he produced a body of work that involved air, earth, water and fire, with fire becoming central to his search for the immaterial. This is reinforced in the title of a book written by Pierre Restany and Klaus Ottmann: Fire at the heart of the void.31 Along with Klein and Beuys, numerous performance artists are referenced in Izkliede, including Gunter Brüs, a radical Viennese performance artist and Valdis Abolins, a Latvian artist whose family moved to Germany as refugees when he was five years old and whose name appears inscribed in one segment, with the word ‘Abo’ below it. For many Latvians this is readily recognisable as the nickname of Abolins, which translates as ‘little apple’. In an Australian context the word has disturbing connotations, revealing the capacity of language to shape our feelings. The way the word is painted is taken from Gordon Bennett’s work History painting (excuse my language) 1992, a work that exposes racist language and asks questions about the present and past. As Bennett said, ‘To be free we must be able to question the ways our history defines us’.32 In Izkliede the power of symbols, like language, can have multiple meanings, as in the swastika on the incendiary matchbox. Until the Nazis adopted this symbol in their cause, which resulted in the deaths of millions of people, it had been used by many cultures for over 3000 years to represent the sun, life, power and good luck. One of the most obviously political images in Tillers’ Izkliede is Joseph Stalin’s head, surrounded by the amorphous masses. This image is taken from a drawing by Gustav Klucis, who was born in Latvia in 1895, joined the Czarist army in 1914–17, and chose to side with the Russian revolution. By the 1930s, however, his art was being censored and in 1938 he was arrested. To this day it is not known for certain whether he was later executed or sent into exile, calling to mind the great suffering and resilience of many of the Russian people over time. Klucis’s works are now held in many public collections around the world, including the National Gallery of Australia and the Latvian National Museum of Art. Tillers’ Izkliede made a strong impact on many who saw it when it was first exhibited at Sherman Galleries in Sydney, in 1994. His friend, Chilean artist Eugenio Dittborn, wrote the catalogue introduction, titled ‘Notes for a small genealogy of the canvasboard in the pictorial work of Imants Tillers’. He noted that in Tillers’ paintings the boards ‘sustain his pictorial inscriptions and are camouflaged by them’. He recognised that, along with their physical structure continually oscillating between being and non-being on the walls, the boards – with their many fragmented images – convey ruptures in a symbolic sense; carrying within them ‘the multiple small wounds of diaspora’. As he wrote: In the initial explosion of the work of Imants Tillers – its big bang – there is the gesture of drastically reverting the subordinated position of the carton in the pictorial tradition in general, and Impressionism in particular. Tillers’ refusal to work on the pictorial canvas, single, homogenous and continuous in the physical nature of its surface, is the ‘mise en scene’ of a support that is at once multiplied and divided, whose composite and centripetal body exhibits its cuts, forcing a reading of them as an inevitable stumbling place. An assembled and dismountable surface that forms a grid, which is not a representation but the result of multiple juxtapositions. These canvasboards united in constellations in each work by Tillers, seem to tell us that the visible secret of their insubordination lies in the impossibility of covering their small wounds – joints, cuts – In a review of Tillers’ exhibition, Evelyn Juers wrote that ‘the patterns of disclosure are now becoming the real force in the work’ and responded to the idea of different ways of seeing from within and outside the painting. ‘The faces establish a curious reciprocal attachment between the eyes of the viewer and the “eyes” of the work. One … even breaks the impassive staring silence with the challenge to “just imagine the painting sees you but you don’t see it”. What a thought.’ She continued: The masculine heads – Carlo Carra’s drunken gentleman about to topple from his pedestal and the painted rendition of a wooden, (and wormeaten?) Baselitz sculpture – have an end-of-reign air about them. The female depictions are more complete. Having escaped the dead-look of a phallic Baselitz we move along to be quizzed by de Chirico’s single instrument of vision: it becomes a question of insight and of equating one eye with one ‘I’.34 The title of the exhibition at Sherman Galleries was JUMP, drawing inspiration from McCahon and the idea of trying to work out which way to jump – how to make the leap to the next stage of the journey. It is worth remembering that in between the Diaspora series, Tillers was painting numerous smaller works. Included in the exhibition with Izkliede was A painting for Greenpeace 1990, recalling McCahon’s Let us possess one world 1955. By the time Tillers painted his version the Cold War as McCahon knew it had ended. As the title of Tillers’ painting suggests, other battles were continuing to occupy the minds of many, including the increasingly apparent need to take measures to protect the environment around the globe, giving fresh impetus to the inscription in the work: Let us possess one world, each has one, and is one. Paradiso 1994 The Northern guests are sailing. The gently sloping shore of the Bay of Finland extends in a bright stripe into the distance. It is as if the water were impregnated with the azure of a clear spring sky; the wind ripples it, creating opaque-violet bands and circles. Nicholas Roerich35 The third work in the Diaspora series, Paradiso 1994, was created for Diaspora in context: connections in a fragmented world, an exhibition organised by Marketta Seppälä at the Pori Art Museum in Finland and which centred around Diaspora 1992. In addition to attempting to secure the source works that had inspired Diaspora, a second major painting was required for the show and by the time the dates were confirmed, Izkliede 1994 had been committed to the exhibition Antipodean currents.36 This meant that a new work was required and Tillers dedicated himself to the task, taking as his starting point the evocative idea of paradise and its layered implications in relation to diaspora. He recalls that from April 1994 when he started, until the work was almost complete in December, it was titled Paradise. ‘I changed the “e” of paradise to the “o” of paradiso when I realised that it formed an anagram of the word “diaspora”.’37 In Paradiso Tillers reflects on the ways in which displaced people, escaping from debilitating circumstances, often held great hopes for the new ‘promised land’. The realities were, however, not utopian. As Tillers notes, ‘Even though migrants were freed from daily oppressions in their own countries, the notion of paradise was hardly a reality. Instead, the circumstances were often quite tough in their adopted countries.’38 For many refugees, like Tillers’ mother and father, escape from the difficult circumstances at the end of the Second World War meant that they had fervent hopes for the future. On the other hand, there was also a sense that over the years their memories of their country of origin became idealised. Tillers recalled that in the course of his first visit to Latvia in 1976, as a surrogate for his parents, he found it to be different from the images of the place conveyed to him as a child: ‘the sense that the “memories” of Latvia which I had before I went of beautiful lakes and forests were but phantoms – not based on lived experience at all. Latvia of course was now a modern country, though impoverished by our standards and not the nineteenth century rural paradise I had half expected.’39 Having decided on the theme of paradise, Tillers came across Jonas Mekas’s book I had nowhere to go: diaries 1944–1954, published in 1991. He described it as ‘a vivid and moving account of how he was forced to leave his native land … like many other Balts during World War II’.40 In his diaries Mekas relates his experiences in a Nazi forced labour camp and then in displaced persons camps, followed by his eventual resettlement in New York. In Paradiso Tillers incorporates the cover of Mekas’s book and the inscription of his words: We are dreaming of bread and liberty Tillers was struck by Mekas’s idea that ‘in such dismal circumstances thoughts of paradise abound. I’d like to know what a twentieth century man would do in paradise, a paradise as we find described in the old books.’ Later, when faced with the prospect of emigration to America, Mekas wrote: ‘A Lithuanian cannot live without nature. You can’t detach him from the wide green fields, from the brooks, the snow, the cobwebs flying through the air in late September, from his forests, fragrant with moss and berries.’42 In Paradiso there are multiple references to well-known and lesser-known artists, and to everyday sources. One of the most striking aspects of this work is that there is an opening out of the composition in both the predominant image and the bold text references. In the centre, the dominant Christ figure was inspired by a reproduction of Sidney Nolan’s Crucifixion 1954, an oil painting on paper, transformed dramatically in scale by Tillers. The figure – The idea of paradise – lost, found, longed for and mislaid – is intimately linked with notions of faith, alluded to in the numerous cross-cultural references to spirituality in the work. An alternative to the conventional image of the cross is the T shape on the left, inspired by Colin McCahon’s adoption of the Greek letter Tau, ‘used by Egyptians and the Israelites as a symbol of life’.43 Just below the Christ figure’s right arm is another indistinct image of him as a child in his mother’s womb, based on a detail of a carving by Aboriginal artist George Mung Mung from Turkey Creek. Mung Mung’s configuration of the Virgin Mary and Christ child is a carved figure with an egg-shaped womb painted on her torso, containing a child. ‘[The baby] stands with legs apart and his arms held high, each limb touching the perimeters of his womb, just as the ideal renaissance body extends its limbs to occupy a circle.’44 In Tillers’ painting he leaves just a delicate imprint to suggest an alternative response to the New Testament story, compared with the more expected image of Christ in Nolan’s work and the seated Christ figure from Mekas’s diaries. Another biblical reference is found in the adaptation of a Nicholas Roerich painting, Madonna laboris 1936, in the Latvian National Museum of Art. Roerich was the inspiration for the first panel painted for the Diaspora series, of the Madonna holding the Banner of Peace, and his re-inclusion here adds to the web of interconnections across the four works. In this instance the mystical aspect is heightened by the dominant blues, the gold of the haloes and the luminous thread linking what is above with what is below. Once again, text references are subtly included over the image, partly inspired by Shusaka Arakawa and Madeline Gins. On the other side of the Christ figure, the word ‘faith’ floats above a Latvian symbol in a vessel, relating to an earlier work of the same title by Tillers that had been appropriated by New Zealand artist Shane Cotton. The use of the word in Tillers’ painting Faith 1988 was inspired by an Ed Ruscha painting that he reinterpreted by adding a traditional Latvian design and situating it within the colours of the Latvian flag, which was still banned at the time. The work was donated by Tillers to the National Museum of Art in Riga. Cotton believed that in the past Tillers had not been aware of the meanings behind some of the Maori references in the McCahon works he had appropriated, seeing his work as fair game for re-appropriation. In an ironic twist, Cotton adopted the idea of misunderstandings and an intuitive response, noting that Tillers’ work ‘contained fortuitous elements’, such as ‘the word “faith” and the plant form with diamond shapes’, relating to aspects of Maori culture that he integrated ‘within the symbolic context of the pot plant’.45 In an interview, Cotton’s Faith 1993 was interpreted as appearing as much a ‘reference to Christianity as Maori belief within postmodern art practice’ – a Christmas scene even – to which the artist replied: ‘These things are to be seen in the work, but not to explain it away. Faith is always a gamble.’46 Tillers would concur with this idea, and in re-appropriating Cotton’s appropriation into Paradiso he continues the idea of an open-ended dialogue. A number of sources came to be included in Paradiso as a result of what initially seemed to be adverse circumstances. When the idea of exhibiting Diaspora 1992 in Finland was first proposed, Seppälä hoped to show the work together with the full complement of images that Tillers had referenced to convey the relationships between them and the transformations that had occurred. As Tillers noted, this turned out to be a very ambitious and difficult undertaking, ‘highlighting the structures of power, hierarchy, value and protocol which operate in the art world and the disadvantages faced by the peripheries. But obstacles and difficulties can sometimes turn out to produce unexpected advantages too. Paradiso was able to compensate for some of the unsuccessful loan requests by incorporating additional sources such as [Georg] Baselitz’s Der Dichter [The Poet] 1965 and Roerich’s Madonna Laboris 1936 which were available.’47 By the time he completed Paradiso in December 1994, Tillers recognised that in the evolving structure of the Diaspora series he seemed to have found ‘a new and immense space of possibilities with regard to both sources and their interrelationships within a painting resulting in a veritable explosion of sources’. He noted that whereas he had quoted from a total of about 200 different artists in over 400 works produced between 1981 and 1992, Paradiso alone encodes information from more than 30 different art sources, including well-known artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Sidney Nolan, Jackson Pollock, Laurence Weiner, Jannis Kounellis and lesser-known artists like Tess Edwards, Julian Dashper, Stranger 29 and Unto Pusa.48 Also important were ephemeral references from daily life: newspaper cuttings, and images and text from photographs he had taken of everyday phenomena that usually pass unnoticed. Tillers had always been interested in the resonance of these things within the imagery and content of his paintings, but now managed to incorporate them more directly, pointing the way for the works to follow. Another shift in the work is the increased scale of the text ‘(this and that) put (here & there)/out of sight of Polaris’, drawn from a Weiner work in the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Weiner has been described as ‘one of the canonical conceptual artists of the 1960s … among the first to dematerialise the object of art into the realm of language and ideas’.49 In his use of a utilitarian but elegant typeface, Weiner’s experimental, text-based works have a formal beauty. He believed that words can have a sculptural quality, not by being written but by being read.50 Tillers responded to the evocative, open-ended nature of the text and found parallels with his process: from considered choices, to malleable, intuitive responses and chance encounters in the rendezvous of images moving from place to place. In Paradiso, as in all of the Diaspora works, there are references to the Fluxus performances of Joseph Beuys. Tillers notes, however, that in this work there is an amendment to a line from Beuys’s Manresa Action: ‘Good day, where are you going? Thorvaldsen Museum. In Paradiso it becomes: Good day, where are you going? To paradise.’ He also inscribes into the work the text from Dimitri Tsaloumas, the Greek-born Australian writer, which relates to his personal experiences of migration: ‘Tell me. Where in geography is this land? Why am I here?’51 By contrast, in the top right-hand corner of Paradiso a sense of place appears in a beautifully painted homage to Aboriginal artist Rover Thomas. The imagery is borrowed from Thomas’s painting Blancher country 1987, which was shown in the group exhibition Identities: art from Australia that also included Tillers’ work. After completing Paradiso in December 1994, Tillers holidayed with his family in Tasmania. They travelled from Hobart to Cradle Mountain National Park and the village of Moina. Near Moina they came across a place called Paradise, with green, rolling hills and views of the high mountains. As Tillers noted, ‘It was the kind of place Jonas Mekas might have liked’.52 Tillers had wrestled with the idea of paradise over many years. He referred to the concept in discussions about his work in the 1980s in relation to mourning injustices of the past and the need to retain hope for transformation in our minds and hearts. If the dream of paradise is tenuous and fragmented, as in Paradiso, it is not entirely ironic. Again, this has a striking parallel with Mekas’s work and philosophy. In his later years, Mekas never gave up on the idea of paradise, despite the extreme difficulties he had faced during his life. In 1979 he made Paradise not yet lost with footage shot in 1977 during his daughter Oona’s third year of life. As Genevieve Yue notes, the title suggests that through his child and family, Mekas finds some hope of redemption, tempered by a wariness of expecting too much. Midway through the section on Lithuania … he recounts a story he heard about Adam and Eve after they had left Paradise. While Adam slept next to a rock, Eve looked back and saw the ‘globe of Paradise exploding into millions of tiny bits and fragments.’ Once ejected, the view back towards Paradise is a fractured one. For Mekas, Paradise can only be seen in ‘tiny bits and fragments’ … To find Paradise, even in fragments, is a rare occurrence.53 In addressing his young daughter Mekas cautions us: ‘But I am not saying, Oona, that things have been that much better ever before. No, at any given time there were only very few women and men struggling to seek out and preserve the little bits of Paradise so that their lives would be more beautiful and the lives of those who would come after them. Paradise cannot be gained without a constant struggle, moment by moment.’54 Farewell to reason 1996 No end This poem, by New Zealand poet John Caselberg, is the partially hidden text in Farewell to reason 1996, the fourth work in the Diaspora series. It runs down the panels under the words ‘farewell to reason’ – the title of a book by Paul Feyerabend – like a mantra. It is at one with the text and images that roll as a continuous ebb and flow across the Diaspora series, inspired by Caselberg’s friend Colin McCahon. The expansiveness of Caselberg’s poem is echoed in Tillers’ painting. Intuitive correspondences run like a metaphorical, invisible thread through the underlying earth colouration, the black-and-white textual references and symbolic images, through the plants, leaves, rocks and snow-covered mountains, and through the implied losses, returns and echoes across space and time, connecting with the pulse of our human yearnings, with an awareness of our shared mortality. The anchoring power of the work comes through the dignified presence of the Aboriginal man dominating the composition. There are numerous symbols relating to mortality and rituals across different cultures in Farewell to reason, including the cross from McCahon’s The five wounds of Christ no. 3 1977–78, and another symmetrically placed cross on the vibrant green cape or chasuble (a vestment worn at mass) originally designed by Henri Matisse for the chapel at Vence. Other sources include the word Nezinams, which refers to a tombstone for unknown Latvian soldiers; a black-and-white graphic image of an Indigenous figure from a work by Eric Thake, reproduced in a publication on Australian art by James Gleeson; and a funerary image, diagonally below the Matisse cape, that is a detail from a work by Chilean artist Eugenio Dittborn. The detail from Dittborn was taken from a drawing of a funerary bundle containing the body of a man and was one of a number of images within a larger whole, titled Airmail painting no. 95: the 13th history of the human face (the portals of H) 1991.56 Among the recurring concerns in Dittborn’s works are the ‘often violent consequences of the encounter between indigenous and colonising populations, an encounter deeply inscribed in the Latin American history and consciousness’.57 In addition, he highlights the ‘disappearances’ of people in recent Chilean history under General Augusto Pinochet. In an interesting parallel with Tillers’ approach to the circulation of images across boundaries, Dittborn’s Airmail paintings have been described as spanning and preserving the international distances between Chile and other countries, generating a dialogue and salvaging fragments of memory through the recycling and renewal of images.58 The idea of recycling is manifested in Farewell to reason: the panels at the top right and left, with the bold lettering of ‘see’ and ‘surf’, existed previously as separate works. The panel on the right was originally titled In memoriam to Ian Burn 1995, a homage to a friend that includes a line of Burn’s text: ‘Sight is forgotten a text assumes the blindness of a picture’. This recalls a fragment of text from Izkliede, about what a painting might or might not be capable of: ‘Just imagine a painting looks at you but you do not see it’. In 1972 Tillers met Ian Burn, who had been working in New York as part of the Art & Language Group and had returned to Australia for a visit. He wrote about Art & Language in his Honours Thesis in 1972, remarking on the theoretical capacities of the group to construct ‘alternative frameworks’ and ‘a transformational grammar to make propositions about art’. Although Tillers had some reservations about aspects of their approach and capacity to communicate to a wide audience, he was stimulated by Burn’s ideas and writings, and by their discussions about ways of looking at and thinking about art.59 As earlier works indicate, Tillers was clearly intrigued by the potency of words, language and typography – both visually and conceptually – in his Diaspora series. In Farewell to reason he again adopts text that has sacred and profane connotations. For example, there is a play with language in using the word ‘surf’, which is an abbreviation of ‘surfeit’ and also refers to the ocean. In a similar play on words, ‘There is only one 1’ recalls Tillers’ earlier quotations from McCahon but is in fact from a Mobil advertisement. Likewise, the single letter K is not an esoteric code but is based on a photo that Tillers took of a K on a cat’s door, while the letters U and R in the upper right-hand corner come from an underground resistance poster. The upper section of the work also includes the first small reference to Rosalie Gascoigne (who had been based in the Canberra region) and her poetic dissembling and reworking of text from signposts of the everyday, using found materials. As in the first three paintings in the series, there are recurring references to Joseph Beuys, but most unifying and resonant is the echo of the voice of McCahon. Patterns of continuity are present in large and intimate signs of remembrance, and in the cycles of nature as metaphors for regeneration in art. This is expressed in allusions to rocks and clouds in McCahon; the spiky, yellow flowering details on the Matisse vestment; the unexpected inclusion of four superimposed panels of leaf imagery, based on photocopies of actual leaves that Tillers made and repainted; and a cut-out shape of a flowering iris that is one of the first references to German Romantic artist Philipp Otto Runge. In the epic picture of Farewell to reason, the Runge image is a modest inclusion. Yet Runge’s art would become another source of fascination for Tillers that would flow in wave upon wave through the next phase of his art, in his Enigma of arrival series of 1997, in Monaro of 1998 and in the Nature speaks series of 1998–2006, signifying Farewell to reason marked the conclusion to a particular cycle of works and provided links with what was to follow. The idea for the Diaspora series had been sparked by the success of the independence movements in achieving the liberation of the Baltic States, but extended to the worldwide phenomenon of diasporas. The nature of Tillers’ response to the question of displacement in the series is non-linear and non-narrative. The paintings themselves are not didactic but rather more about allusions and exchanges. An awareness of specific references can greatly add to and deepen our understanding but the works are not prescriptive. They are associative and multi-directional, open to interpretation with a strong pull towards the mystical. The series suggests that local, social and cultural specificities affect language and the way we think, that cultural diversity is there to be grappled with, and that coexistence is not a given but a process of becoming that is continually evolving. The greater use of text in these works can be seen as a way of infusing the paintings with a sense of the rhythms, repetitions and cadences of diaspora. The links that Tillers drew between an ecological paradigm and multiple interconnections in his art since the 1970s are there in the Diaspora series. They would continue during the ensuing decade in an increasingly direct correspondence with his response to natural phenomena from his base in the Monaro region of New South Wales, where he embarked on another distinctive phase of his artistic journey. 1 Pierre Restany, ‘The Baltic idea’, in Diaspora in context: connections in a fragmented world, exhibition catalogue, Finland: Pori Art Museum, 1995, p. 73. |

| NGA Home | Introduction | Themes | Search | Essays | Learning | Visiting | Previous |