|

|

|

||||

|

Nature speaks: when locality prevails Since we moved to this (some would say) godforsaken, bleak, arid, treeless landscape called the Monaro nearly eight years ago, an awareness of landscape has become inescapable to me. Every journey, on foot or by bus, car or aeroplane, entails contact with the austere vistas of a landscape tempered by heat, frost, drought and decomposing granite. Here I have come to understand what Thomas Bernhard meant when he described gardening ‘in all its possible and impossible forms’. Imants Tillers1 By 1998 the groundwork was set for a dynamic interweaving of two aspects of Imants Tillers’ approach to painting: the web of interconnections between all things and an increasing recognition of the significance of place. The shift in subject matter towards locality was inseparable from the move Tillers made with his family to Cooma in late 1996. At this time he began to re-think the significance of landscape, informed by the varied local environment: the cultivated garden and rocky bushland at their family home Blairgowrie, the expansive terrain of the surrounding Monaro region, and the proximity to the Snowy Mountains. Tillers’ work became infused with a romanticism and austerity that reflected the ongoing conundrum of absence and presence, along with his feeling for distinct changes in seasonal weather patterns – the harsh droughts of summer, the blossoming of springtime, the crisp cool of autumn and the freezing winters. These aspects were revealed in his sensitivity to colour and tonality, and in the open-ended associations between diverse elements. In his art correspondences with landscape make their presence felt in a non-literal way – as evocations of nature through text and layered visual elements.2 Moving to Blairgowrie, their home in Cooma, presented Tillers and his family with a dramatic shift in lifestyle that offered new opportunities, but also involved sacrifices and hard work. Isidore and Saskia needed to be settled in new schools, a studio needed to be set up in the house for Tillers, and the house and garden were in need of considerable restoration. Using her experience from the past, Jennifer Slatyer spent much time working on the garden, planting fruit trees in the orchard, establishing an organic vegetable garden, and re-planting and shaping the main garden in front of the house. She also became involved in the Cooma Community Landcare group, in local bush regeneration and working with the Monaro-Ngarigo Aboriginal Reconciliation Committee on the restoration of Ngarigo Lambie Gorge, which adjoins their property. In a range of ways Tillers and Slatyer were taken with the special ecological nature of the Monaro region – with the purity of its water, and basalt and granite rocks. Inspired by Shusaka Arakawa’s and Madeleine Gins’ ideas, they even proposed that it might be a suitable location for a Site ofreversible destiny – ‘to set up a different form of architecture in the landscape that would produce an alternative way of living and a different kind of evolutionary direction’.3 This somewhat incredible, utopian concept was discussed with Arakawa and Gins on several visits to New York, but faltered for a range of reasons. On a more practical level, Tillers found that their location presented new challenges, particularly as he doesn’t drive. At times he felt he was leading a split existence between Cooma and Sydney, and as though he was going into exile. On the other hand, he also relished retreating back to his new abode in the vast Monaro landscape – travelling through the countryside by road or viewing it from above. ‘I still get excited flying into Cooma. It is quite wonderful because from Sydney onwards … you are aware of this vast landscape underneath you and over the Monaro it is really pretty featureless and you feel like you’re coming down to land in the middle of nowhere.’4 Tillers also enjoyed his frequent excursions into the landscape with locals to discover particular landmarks and volcanic outcrops, such as The Brothers, and he began compiling lists of place names that sounded like readymade poetry for inclusion in his work. Tillers also went on painting excursions into the landscape with the local Cooma art group, the results of which became incorporated in his work. In other ways his approach to painting in his canvasboard system remained consistent with what had come before, as he continued to draw upon a range of sources and to be open to serendipitous correspondences in art and daily life.

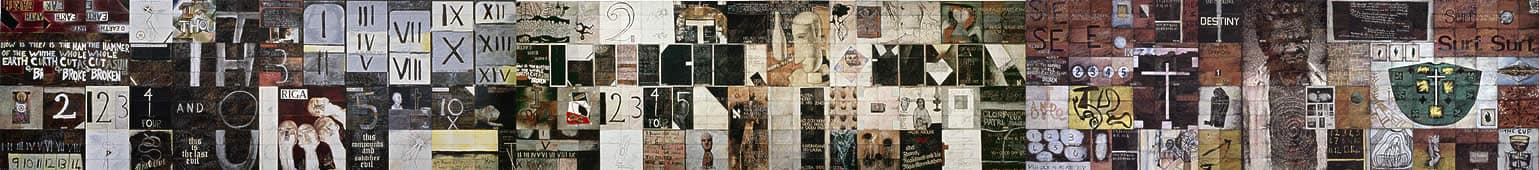

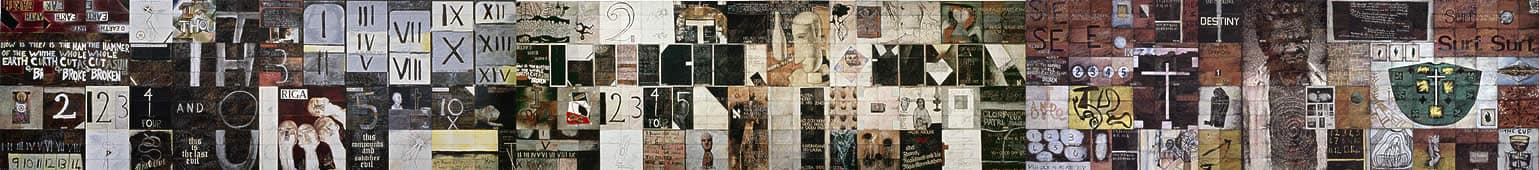

Landing sites: A, B, C 2000 Of its own volition (density) the material moves from place to place. Lawrence Weiner5 The words quoted above from conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner are inscribed by Tillers in his painting Landing sites: A, B,C2000.They suggest the migrations of ideas and images from place to place across the globe, through mechanical reproduction and air travel that has shaped much of our thinking in the twentieth century and a rationale for Tillers’ art over several decades. The idea has a special resonance in Landing sites: A, B, C, which evolved through a process of re-constitution and recycling over a decade. The work had its origins in The bridge of reversible destiny 1990, comprising a painting A vision of infinite space on the wall, and stacks of blank and painted canvasboard panels on either side. After a show at the Yuill/Crowley Gallery in 1990 the work was painted over. In 1998 Tillers was invited by a Korean curator based in New York, Yu Yeon Kim, to recreate the work for a group exhibition, Five continents and a city in Mexico City.6 Tillers painted a second version of A vision of infinite space and sent the entire contents of his studio in Cooma to Mexico, to constitute the stacked elements. Yet another version of the work was included in the WORD exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, in 1999. It was this version, incorporating the large letters IT with two delicately drawn beacons inspired by Shusaka Arakawa, that was the basis for Landing sites: A, B, C. On the left Tillers added to his re-working of Max Ernst’s collage The voice of theHoly Father 1930. While the adaptation of a nineteenth-century figure in Ernst’s work appeared to Tillers to be opening the ‘Book of the 20th century’, he thought of it closing on the brink of the new millennium. The idea of the book also resonated with the idea of the canvasboard system as the Book of Power, and with Stéphane Mallarmé’s interest in the book as a holistic system containing multiple fragments. In Tillers’ work the easel on which the book rests has the joined letters IT at the top, echoing the large architectural letters that are his own initials and that recall the large letters ‘I am’ in Hiatus 1987, inspired by Colin McCahon. Intersecting with the crossbar of the large T is an open book that would recur in multiples in one of Tillers’ Nature speaks works, with the word ‘excerpt’ across it and the panel count of his Book of Power: 60499–60799. The open book recalls Mallarmé’s interest in space, particularly in his poem Un coup de dés, in which the basic unit is no longer the line but the page or the double-page. For Mallarmé, space also suggested ‘the Poet’s confrontation with the white page, the Philosopher’s with the Void, and the Everyman’s with the “wrecks and errors” … of experience’.7 In Tillers’ painting, words from Un coup de dés correspond with variables within the canvasboard system, with numbering and constellations of images. As the inscription in the work reads: The number/were it to exist/were it to begin and were it to cease/were it to be numbered/were it to illumine/… nothing/will have taken place/as if/except/perhaps a constellation. Other components nested in Landing sites: A, B, C include various landscape paintings. A number of them were painted by Tillers during outdoor painting excursions with Chris Graham and the local Cooma art group. Rather than relying on purely literal representation, these small paintings include the repeated letter T reflecting the Tau cross in McCahon’s work. Adding another dimension to the idea of material moving from place to place, several small Aboriginal paintings from central Australia, discovered by Tillers in airport shops, are applied to the surface of the work. The two distinctive approaches to landscape reflect the coexistence of different ways of conceptualising place. This idea is reinforced by the Arakawa-inspired beacons that radiate numerous fine, inter-connecting lines across the surface, emphasising chance meeting places of material from different contexts. Likewise, the movements backwards and forwards in time – incorporating references to art from other centuries – also appeared in works like Monaro 1998, fusing elements of a sublime German Romantic tradition with Tillers’ feeling for the Monaro region.

Monaro 1998 [Philipp Otto Runge] set out to develop a totally new art of symbolic forms and colours. This he referred to as landscape, although it ranged far outside a conventional use of the term to include a combination of childlike genii and flowers arranged in hieratic symmetry. Nature for Runge was a manifestation of the Divine, and he was really seeking to communicate this sensation of our kinship with the whole universe: the sense of ecstasy when everything harmonises in one great chord. William Vaughan8 Whereas in Landing sites: A, B,C2000 the radiating lines from Arakawa provide the inter-connecting threads across the work, in Monaro 1998 it is the multiple faces of cherubim that provide the flowing background imagery across the surface. They were inspired by Philipp Otto Runge’s drawing Die Cherubsglorie [Cherubim] 1809. Born in Copenhagen in 1777, Runge was a contemporary of Caspar David Friedrich. Like Friedrich, he sought ‘to communicate the intense feelings that they experienced in the presence of nature so clearly that “this emotion of our souls should become as palpable as a handshake and a glance”’.9 For Runge, who died at thirty-three years of age, art was ‘not the imitation of nature – which he saw as “utterly prosaic” – but rather another form of it’.10 Taking a mystical approach, he conceived of a holistic, cyclical environment relating to times of day and the seasons that in turn relate to the cycles of human life. Like other Romantics, Runge wanted his paintings to be viewed to the accompaniment of music and poetry to achieve a fusion between art forms. His Cherubim, which was such an inspiration to Tillers, comprises detailed, incisive drawings that were meant to be transferred to his large painting Morning 1809, although this was never carried out. Tillers first became aware of Runge’s works in 1996 when he travelled to Amsterdam to participate in a group show, The world over/under Capricorn at the Stedelijk Museum, co-curated by Wystan Curnow and Dorine Mignot. On show at the same time in the Van Gogh Museum was an exhibition of the work of Friedrich and Runge, which included the drawing Cherubim. Tillers was struck by the modernity of this early nineteenth-century image, by its insistent multiplicity and re-conception of nature. He first painted a couple of small works that included one or two cherubic heads, followed by a series, titled The enigma of arrival, that featured them. It was in Monaro, however, that he sought to convey a sense of Runge’s whole drawing in the field of faces. Conceived as an extension of the Diaspora series, this work was distinct from the previous four works conceptually and compositionally. These differences can be noted in its wave-like structure that opens out into space and ‘in its quietistic mood; its silvery grey, pink and bronze hues; and its subtle tonalities, echoing the bare hills and purified light of the Cooma region’.11 The ideas for the work were put forward in a proposal for the Lowenstein Sharp Fellowship at the Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne. Betty Churcher, the judge of the Fellowship for that particular year, selected Tillers, noting: Imants Tillers’ proposal … centred around the move of the artist and his family to Cooma in the High Country. Tillers pointed out that the Australian imagination has, for the most part, been directed Westwards to our dry interior – to the ‘outback’. He wanted to look Eastwards to the High Country. The proposal was irresistible. With so many ‘givens’ governing his work, how would the High Country nudge its way into the obsessive concerns of this very considerable artist?12

The work was first shown in Cooma at the Raglan Gallery where it had been broken down into six-panel modules to fit into the available spaces, in much the same way Diaspora 1992 had been shown in the National Museum in Riga. The title of the exhibition, Prayer for rain, reflected the concerns of many in the region about the prolonged drought that had begun to severely affect the landscape and that would continue until 2005. Apart from the tonalities of the painting, references to the experience of the environment are both direct and by association. They include small landscapes undertaken on outdoor painting excursions and a reference to a little mountain – similar to the hilly, rocky outcrops around Cooma – drawn from Sigmar Polke’s The three lies of painting 1994. Like Polke, Tillers was interested in the idea of landscape painting as an illusion, incorporating the materiality of canvas and stretcher in view. Another contemporary source that can be read in various ways is the misshapen skeleton, taken from a small newspaper reproduction of a work by British artist Chris Ofili. In a sense Tillers identifies our human mortality with cycles in nature. After living in the city for most of his life, he was struck by the reminders of mortality in the landscape where skeletons of animals, particularly sheep, are seen on a regular basis. As he said, ‘It is ever present and I suppose it is a reminder of how harsh the landscape or country is … In the city you’re protected from it.’13 The inscription ‘We have decided not to die’ – the title of an exhibition of Arakawa and Madeleine Gins’ work – suggests the idea of continuity beyond our physical passing, while another transcendent dimension appears in the form of a ladder between earth and sky drawn from a Robert Fludd engraving. This ladder extends from a rock in the foreground into the illusory landscape and up to an emblematic sun bursting through the clouds. In 1998 Monaro was exhibited with works by Jon Cattapan, Rosalie Gascoigne, Anthony Hamilton and Kathleen Petyarre in an exhibition titled Expanse, curated by Ian North for the University of South Australia Art Museum. The show aimed to ‘cut across the details and debates of recent Australian art history to indicate productive new ways of being in Australia’ by taking into account, among other things, the ‘politics of ecstasy’.15 As North has commented in relation to Monaro: ‘Polke’s little mountain rhymes with the Three Brothers, actual volcanic cones south-east of Cooma, while the grey light of the Monaro links it to the work of Rosalie Gascoigne, who scours the same region for shards of material to act as its metaphor, as well as to essay into the wider interior.’16 Tillers’ field of cherubim also corresponds indirectly with Gascoigne’s major work Monaro 1989 in its feeling for the rolling expanse of the local landscape. A work that is closely related to Monaro and Landing sites: A, B, C, is Mexico, etcetera 2001. Not long after arriving in Cooma Tillers’ attention was drawn to a homoclimatic map of the Monaro and South Coast of New South Wales regions, which compares locations around the world in terms of their microclimates. Tillers was fascinated to discover that this map linked Cooma with Guerrero City in Mexico.17 In a remarkable trajectory of coincidences, not long after discovering this map he was invited to participate in a group show, Five continents and a city in Mexico City, and in 1999 Charles Merewether curated a retrospective of his works at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MARCO), in Monterrey in Mexico’s north. The director of the museum, Xavier López de Arriaga, noted that since 1991 MARCO had opened its doors to artists from parts of North and South America as well as Europe and Asia. ‘Now we turn to Australia, a distant country … In the milieu of contemporary art, the contributions from Australia have been, and are, of great relevance, exemplified by the work of the artist Imants Tillers which MARCO is pleased to present for the first time to its public in northeastern Mexico.’18 Tillers’ Mexico, etcetera was painted partly in response to the serendipitous connections between Cooma and Mexico, in keeping with his interest in fluid, open-ended interconnections within his own working process. Fittingly, the work was later selected for Synergies, an exhibition curated by Nigel Lendon and Howard Morphy shown at the Drill Hall Gallery of the Australian National University, Canberra, in 2003. As the curators noted, the idea of synergies ‘refers to the process of sensing similarity in difference, seeing the way things may fit together, work in harmony or contribute to a dialogue. Synergy is unforced likeness.’19

The view from K 1997–98 In von Guérard’s [work] the chaos of the rocks, with ice and snow-covered slopes and peaks, and dark shadowy chasms reaching far down below the piled up columns of nature’s masonry, are produced with wonderful effect. This picture alone is a complete rebuttal of the theory, if such a theory is now held by anyone, that Australian scenery possesses no elements of the sublime. Review in The Ballarat Miner, 186320 A painting pre-empting Tillers’ large body of work that became known as his Nature speaks series is The view from K 1997–98. It both pointed the way forward and echoed the past in its recollection of his earlier painting Mount Analogue 1985 (p. 28). Since the early 1970s Tillers and Jennifer Slatyer had gone on periodic camping trips and walks in the Snowy Mountains; three decades later, with two daughters in tow, the snow country near Cooma was an attraction of living in the area. Adding to the surprising interconnections between Cooma and Mexico City, Tillers discovered a further correspondence in relation to Eugene von Guérard’s painting that had inspired Mount Analogue. As he wrote: ‘It is a little known fact that von Guérard’s Mount Kosciusko 1863 had gone to a private collection in Mexico of Senõr Alfonso Ortega Urgaoe, until Daniel Thomas discovered it there in 1973 and brought it back to Australia.’21 Compared with Tillers’ Mount Analogue the later work, The view from K, is less literal in its details of specific features and more an abstracted evocation of the cold, atmospherics of mountains densely covered in snow. In this instance he was inspired by the spareness of a lithograph of von Guérard’s work North-east view from the northern top of Mount Kosciusko 1863.22 In The view from K Tillers recalls colonial endeavour, recording the names of those who went on the expedition of 1862: von Guérard, von Neumayer, Weston and Twynam, and the dog, Hector. Floating in space are names of particular sites: Jagungal and Watson’s Crags. Another text reference is Lawrence Weiner’s work ‘Stones’ that conveys the sculptural properties of words and their poetic associations. Weiner sometimes placed ‘sculpted words’ in the landscape, setting them apart from the many competing signs in urban contexts. As he said: It makes it harder to place a work in an urban environment that uses language, the same as it’s harder to be a street busker in an urban environment. If you come across someone playing a flute in the middle of the field you are more impressed and immediately get into it.23 In contrast to Mount Analogue, where the textured surface was built up using oilstick, here the paint is applied more thinly and delicately, layer upon layer. The additional element of text is carved with a scalpel into masking tape that itself acts as a way

Nature speaks 1998–2006 The poet has no direct relation to, and still less ownership of, the poem. He cannot lay claim to what he has written. And what he has written remains anonymous, even under his name. From the late 1990s through to 2006 Tillers has been working on his Nature speaks series. Drawing upon a recurring poetic analogy of symbolist poets and artists, the title suggests that nature has its own voice or language. Rather than imposing The Nature speaks series comprises over 100 sixteen-panel works. It is like a microcosm of the canvasboard system or, as Graham Coulter-Smith has suggested, like a system within a system, akin to Russian dolls that fit one into the other.26 Within this subset of the larger pattern there are multiple variations, as well as certain constants. As Tillers noted: At first glance the series appears to proceed like an algorithm because of the repetition of certain elements within each work – like the word ‘horizon’; the Mallarméan mantra ‘A throw of the dice will never abolish chance’; the Tau cross of Colin McCahon’s ‘load-bearing structures’; and the ubiquitous cherubim of Philipp Otto Runge from his unfinished Gesamtkunstwerk ‘The Times of Day’.27

In the series a sense of locality is at times suggested by the web and scatter of text references and place names. In reciprocal patterns or constellations of ideas and images the series evokes the open landscape, fine mists floating high in snowy mountains, the parched cracked earth of the outback moving from afar into the viewer’s consciousness. The series moves from expanse into the realm of the intimate garden, where a transplanted European lily blooms outside the studio window, evoking Philipp Otto Runge. A feeling for nature is there in the luminosity of the work: in warm tonalities of summer and cool hues of wintry days, in the afterglow from intangible rays of the sun, transmuted to the sensuality of paint applied layer upon layer to the canvasboards on the studio table. In Nature speaks we feel the space of the landscape. This awareness of space affects our sense of time. It impacts upon the length of time it takes to travel from place to place; it slows us down and makes more space for reflection. In the series Tillers responds to nature from diverse perspectives. Reflecting on connections with landscape, he could not overlook the power of much contemporary Aboriginal art. While Nature speaks VI 1999 recalls paintings by Emily Kam Ngwarrey, works such as Nature speaks: AD 2002 were the result of collaborations with Michael Jagamara Nelson (discussed in the following chapter). In these works space is seen from above. In contrast to repeated references to the horizon, the alternative inscription appears in a number of works: ‘There is no horizon’. In Nature speaks (Kosciuszko) 1999 and Nature speaks: D Tillers includes a figure which closely resembles Caspar David Friedrich’s The wanderer above the mists c. 1817–19. Light transforms the figure into a ghostly silhouette but he is separate from the natural world that is the source of awe. Comparing Friedrich with Runge, art historian William Vaughan noted that Runge’s most effective picture is ‘an extract from his cosmology’, whereas Friedrich’s pictures are single moments. Vaughan wrote: ‘Friedrich painted precisely the paradox Runge wished to resolve: man’s yearning for the infinite and his perpetual separation from it.’29 If Tillers allows the cool, romantic light to envelop the dreamlike atmosphere of Nature speaks (Koskiuszko), Nature speaks: D is more complex in its layering. Across one layer he transcribed and transformed a diagrammatic, abstract painting by the Art & Language Group, titled Index: incident in a museum (Madison Avenue) XIV 1986. The amplified dot-screen goes back a long way in Tillers’ work to paintings like The hyperborean and the speluncar 1986 (p. 24), where the idea of the dots in printed reproductions suggests different ways of seeing and thinking about art. In Naturespeaks: D it also evokes constellations piercing the night sky. In many works in the Nature speaks series place names and phrases are inscribed into the works, both as a tangible way of locating place and as poetic evocations. At times they appear almost like haiku poems, as in Nature speaks (Kosciuszko): Mount Kosciuszko/Blue Lake Creek/Guthega Pondage/Island Bend/Lake Jindabyne/Dalgety/and so forth/ The Taking another trajectory in the glowing Nature speaks:AT 2002, we travel from Bunyan to Polo Flat, and on to Cooma, Four Mile, Coolringdon and the Arable Road, through to The ‘Jenny’ Brothers, Cooroo, Kybeyan and on to Myalla, Nimmitabel and Gaerloch. These are all places around Tillers’ current home – the signposts of different cultures. With the additional inscription of ‘out)back’ in this work we are reminded of a journey that he made into the interior of Australia in 2000, also recalled in Nature speaks: BK 2004. In April of that year Tillers and fellow artist Graham Fransella were invited by Melbourne art consultant Vic Stafford to travel by light aircraft through the centre of Australia. The itinerary was inscribed in one of the works: Cooma, Mildura, Broken Hill, Coober Pedy, William Creek, Lake Eyre, Alice Springs, Falls Creek, Bungle Bungles, Kununarra, Faraway Bay. It may seem ironic for a postmodernist artist who had questioned the relevance of locality in the 1980s to embark on this epic journey and to spend his fiftieth birthday at Uluru, yet the experience was an enlivening one for him, coming at a time when his deepening feeling for place was resonating in his art. As he wrote, ‘it was an exhilarating and panoramic experience that changed my perception of our vast and beautiful continent’.30 He elaborated on these ideas in an interview with Ashley Crawford: I’d kind of avoided [visiting the centre] because I thought it would be such a touristic experience. But then, it’s amazing. It’s a truly stunning, amazing place. I suppose I’ve fought against the landscape tradition … but I think it’s something you can’t ignore and I don’t want to ignore it now.31

While connecting with a landscape tradition, Tillers was also informed by conceptual ideas, such as those of Ian Burn in the layering of language in his Value added landscapes series.32 While the subject of his art changed, his approach to painting was much the same. As Crawford remarked, Tillers had not lost his tight, graphic sensibility or his penchant for quoting other artists: ‘one canvas is a homage to Rosalie Gascoigne. But, rather than being cool exercises, the paintings glow with an almost romantic response to the landscape.’33 In some Nature speaks paintings disconnected letters float like musical notes across the veils of colour. In Nature speaks (millennium) 1999 they suggest sounds like ‘woodwind’ moving over the intricate layering of elements, including the torso of the Max Ernst figure that would recur in Landing sites: A, B, C 2000, surfacing here like a dream shadow across a landscape of mind. In Nature speaks: BV 2004 Tillers transcribed text discovered by his daughter Saskia on the computer she uses in a corner of the studio. As she noted: I stumbled on them … it is purely an accident that these letters and symbols appeared. What happens is that if the computer can’t read a particular file, it will come up in this strange code … When I first saw it I showed it to my dad and he found it amazing and asked me to print it out for him. And the next thing I saw it was in one of his paintings!34 In the broad spectrum of the Nature speaks series repeated elements such as the T shape, the Runge cherubim and the word ‘horizon’ provide a rhythmic interplay across the whole. Another repeated code in this system is the word ‘entry’, with the letters that form part of the title, such as AU, floating in the space. These were gleaned from a small, personal telephone directory in which the alphabet ran along a shape that looked like a horizon line, recalling earlier references sourced from daily life. Throughout the series the mantra from Mallarmé ‘A throw of the dice will never abolish chance’, inscribed in blue around the edges, is a continual reminder of the importance of chance correspondences that run like a thread through all of the works. Having reached his goal of creating 100 Nature speaks paintings Tillers kept going. In the three most recent works he emphasises the idea of continuity in his art and the passage of time in general, with words from WG Sebald: ‘for years now’. This also corresponds with his interest in cyclical patterns in Runge’s nature-based art and innovative thinking. As a homage to this artist and a reminder of his own intimate ‘conversations’ with nature from his studio in Cooma, Nature speaks: F 2005 comprises glowing panels incorporating the traces of angelic heads with flowing inflections, a solitary iris from Runge and the words ‘that soil of irises (Blairgowrie)’. The series concludes – for the time being, at least – with Nature speaks: G 2006, a work that feels as subtle as a whisper, a space for quiet reflection in which the horizon line has disappeared entirely. Blossoming 6 2005 The seasons rush through my mind in their four incarnations – flowering, procreating, bearing, dying – so that my desire for this eternal miracle is continually sparked. Philipp Otto Runge35 Towards the end of 2005 Tillers had completed two bodies of work that overlapped with the Nature speaks series: the Outback series started in June 2003 and the Blossoming series begun in February 2004. In the catalogue for his exhibition of these works, Land beyond goodbye at Sherman Galleries in 2005, Tillers noted the inspiration of Philipp Otto Runge in the Blossoming works, which described a particularly European ‘rhythm of four seasons’ in contrast with the experience of many in urban and rural Australia. It was, however, a rhythm Tillers experienced at Blairgowrie where the climatic conditions allowed for the planting of European gardens. As he wrote: [The] early European settlers to Australia, alienated from the strange landscape they found themselves in, imported their beloved plants (and animals) and created familiar gardens for themselves. The place I live and work at Blairgowrie in Cooma is just such a European sanctuary (dating from the nineteenth century) in the midst of the dry, austere and treeless landscape of the Southern Tablelands – the Monaro – and the works in the Blossoming series take as their point of departure aspects of this experience. It could be the flowering of Jacobean lilies … the grove of birches in autumn, the mist rising in the morning, a crystalline frost or the stunning transformation of a snowfall that suggests, for me, a real or imagined connection with northern Europe.36

Tillers noted a sense of connection with his own artistic lineage or genealogy that extended across time, ‘from the great European Romantic artists such as Runge and Caspar David Friedrich through expressionism and surrealism to the contemporary masters I admire and seek to emulate such as Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz’.37 This lineage also connected with aspects of his familial past. While the exhibition was still on, Tillers found some pages from his Daily Research journal relating to a visit he had made to Bremen, Germany, in 2002. He travelled there for a group show, Kunst nach Kunst [Art after art], that included his work. The visit also provided him with the occasion for personal reflection: Bremen was the departure point for my parents – the first stage of their ‘trip of a lifetime’ to Australia, after years in D.P. [displaced persons] camps in Germany immediately after the war. On my own trip to Bremen I was still trying to come to terms with the death of my father in December 2001, who incidentally was named Imants Tillers. When the obituary appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald many people thought that I had died. (Perhaps part of me did!)38 Spring in the garden at Cooma in 2005 was extraordinary. After the prolonged drought a bout of rain resulted in a profusion of growth and the fruit trees were brimming with blossoms. In contrast, the trees in Tillers’ works Blossoming 5 and Blossoming 6, both painted in 2005, are bare of blossoms. Their forms were based on Egon Schiele’s Autumn tree in turbulent air (also known as Winter tree) 1912. In his own way Schiele, like Runge, saw parallels between nature and human experience, and his trees – with their strong, linear emphasis and pared back, fractured branches or limbs – suggest a physical and psychic dimension. In Tillers’ Blossoming 6 such correspondences are heightened in the emission of fine, reddish lines, reminiscent of a heart that keeps the body alive. While the broader lettering recalls his admiration for Rosalie Gascoigne, smaller words, delicately inscribed like the softest utterance over the surface, reflect a state of anxiety: ‘I need to find breath … I cannot breathe’. These inscriptions are among the most directly personal references in Tillers’ art. Drawn from conversations with his mother, who was suffering from clinical depression at the time, they echo wider concerns of loss and displacement that run through his own art. Yet, if there is a sense of being in perpetual mourning – the title of an essay he wrote in the Venice Biennale catalogue in 198639 – there is also the perpetual hope of regeneration. In this regard Blossoming 6, shown in the last room of Tillers’ exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, resonates with Runge’s poetic words: Artistically speaking, the last [image] should always be that of spring, that time of blossoming born of previous devastation that itself gives birth to the future.40 By late 2005 Tillers’ mother was out of hospital and on the road to recovery. Around this time he also expressed a partial reconciliation of his own sense of a ‘split personality’, between his Australian self and his inherited Latvian self, through living in Cooma with its change of seasons and proximity to nature. As he said, ‘The method of appropriation or quotation has persisted but the difference since being here is that I am somehow anchored by a specific location … Whereas in Sydney I was kind of disconnected, a feeling of locality is very particular here and I think that has supplied a missing element in a way.’41 This does not imply a neat resolution but recognition that it is possible to live and work with ambiguities and contradictions. In a sense this has always been part of the work, although in recent times the articulation of this idea, along with his feeling for the natural world, has given him a greater inner acceptance and freedom. Although Tillers is not religious in a conventional sense, his attraction to Runge’s angels and the inscriptions of repeated words – such as ‘prayed for’, ‘empathy’ and ‘surrender’ – are part of a growing dimension in his art to find symbols of healing and protection. This relates to aspects of his personal life, in the wake of his father’s passing and his mother’s ill health, to the interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures, and to a world that appears so often in crisis. Another aspect of Tillers’ work that has evolved in the present is his interest in an ecological framework. While the recent work has come to connect more closely with the environment, ideas around ecology informed debates in the 1970s about the mutability of art, which led to the inception of the canvasboard system as an interconnected whole of multiple parts continually open to regeneration, recycling and reinvention. A holistic vision corresponds with Tillers’ continuing interest in physics and a metaphysical dimension. As one of his favourite authors, Fritjof Capra, writes: Deep ecology is rooted in the perception of reality that goes beyond the scientific framework to an intuitive awareness of the oneness of all life, the interdependence of its multiple manifestations and its cycles of change and transformation. When the concept of the human spirit is understood in this sense, its mode of consciousness in which the individual feels connected to the cosmos as a whole, it becomes clear that ecological awareness is truly spiritual.42 Epilogue: Telepathic music 1994and Art is an action 2006 Not long after moving to Cooma, Tillers and Jennifer Slatyer were at a country auction. Tillers recalls that he saw a very large nineteenth-century Bible and opened it to a page that included the following text: ‘Lest for want of tillers the land be turned into a wilderness’ (Genesis 47:19). Needless to say, they had to bid for it and this extraordinary book has a special place in the library. The idea of such serendipitous coincidences and the continuity of memory inform the interwoven aspects of Tillers’ art. Like the dismantled stacks clustered in the artist’s studio, themselves containers of memory, his work goes beyond a straightforward, linear trajectory. Instead, it moves back and forth in time. Like Stéphane Mallarmé’s Le livre it can be read from different starting points and in the re-reading new possibilities can emerge. At times the reworking of an idea can be invoked by an image that appears out of the blue. This was the case for Tillers in 1994 when he was researching an essay, ‘Was it Fluxus speaking?’, for a catalogue on performance art in Australia.43 It occurred when he came across a reproduction of a work by Fluxus artist Robert Filliou: Telepathic music no. 5 1978, an installation of thirty-three music stands that strongly reminded him of his own work Conversations with the bride 1975 (p. 6), which included similar stands. This serendipity prompted a new work. As Tillers noted, ‘Since I could not believe that Filliou could have known my work or been influenced by it, I decided to work on a new piece … using ready-made music stands which could perhaps interrogate this uncanny correspondence, this acausal connection between us’.44 Initially he struggled to find a set of images to place on the stands, which he moved around the studio in different configurations. The solution appeared in an unexpected way. As he explains: For on one morning, at about 9.30 am on the 12th September 1994, the wall adjacent to where the music stands had been left the night before was unexpectedly illuminated with ciphers of light, hieroglyphs, or musical notation – indeed the traces of telepathic music. A decade later, music of the auditory kind plays an important part in the life of Tillers and his family. His older daughter, Isidore, plays viola and is studying at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music; his younger daughter, Saskia, is a budding cellist. Slatyer fosters their musical talents and every week conducts the local music group that Saskia performs in. Isidore also continues her involvement in performances for the Latvian Society in Sydney that she attended on Saturdays when she was growing up. Apart from live music that filters through the house at Blairgowrie, Tillers often listens to recorded music while he works in the studio. In the making of his art, which has always been predominantly studio based, he continues to work on small panels at his desk and on the floor. Completed multi-panelled paintings are installed on the wall although large works, like his major painting Terra incognita 2005, can only be seen in sections in the studio. A performative dimension of the work has been integral to Tillers’ practice since the 1970s. It informs a basis for the canvasboard system beyond easel painting, which is akin to a continually forming and re-forming series of actions. In the early 1990s Tillers undertook a group of black-and-white canvasboard paintings, recalling the abstract-expressionist actions of Jackson Pollock, who also painted looking down at the work laid on the ground. In time a number of these works have returned from exhibitions and remained stacked in Tillers’ studio. In recent times they have been revitalised in the installation Art is an action 2006, which shows them as a number of separate stacks, one for each painting. There is a delicious irony – befitting even Tillers’ early mentor Marcel Duchamp – in this re-reading of the past from the present, turning the idea of self-expression, through the art of another, into self-contained memories in stacks. In Tillers’ exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia in 2006 this work is both a reminder of the artist’s distinctive working methods and of the interplay of absence and presence, disappearance and appearance in the work. The stacks are also a counterpoint to the large scale of some of his most accomplished paintings. The metamorphosis of works from stacks to gallery walls are in turn manifestations of the artist’s self-revelation, filtered through multiple visions, displacements and transformations that become part of the one world of his endlessly intriguing canvasboard system. Seen collectively, Tillers’ art is a revelation of an intense passion for making, and a seemingly boundless curiosity and spirit of inquiry. There is also a sense of an inner search in response to the complexities and mysteries of life that echoes the words of eleventh-century Persian physician and philosopher Avicenna that Tillers noted in his Daily Research journal: How I wish I could know who I am, What it is in the world that I seek.46 Deborah Hart 1 Imants Tillers, ‘When locality prevails’, Heat, no. 8, new series, 2004, p. 114. |

| NGA Home | Introduction | Themes | Search | Essays | Learning | Visiting | Previous |