|

|

|

||||

|

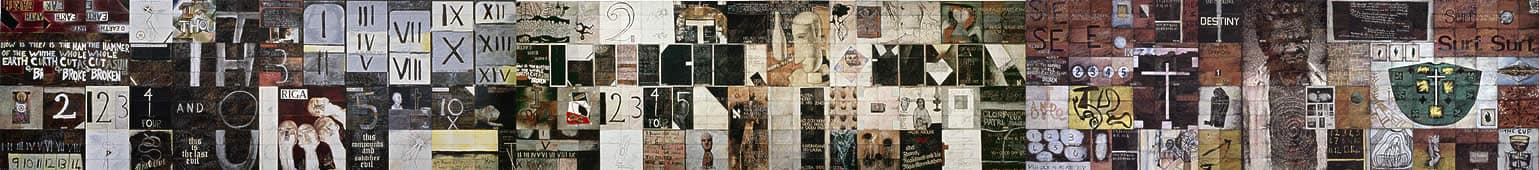

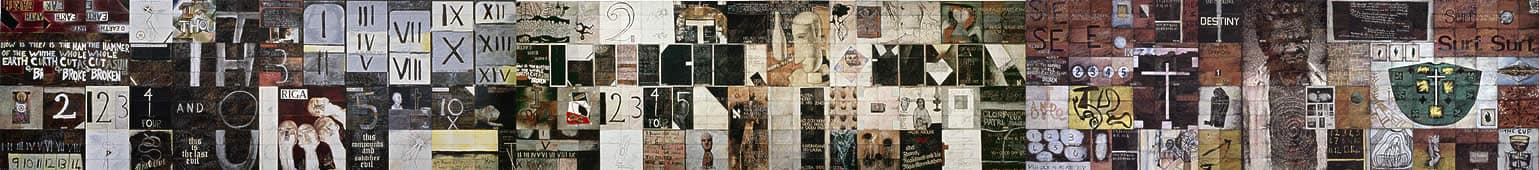

Impossible to ignore: Imants Tillers’ response to Aboriginal art It is possible to write a history of Imants Tillers’ engagement with Aboriginal art that sees it in progressive terms, reflecting at the same time a more general movement in Australia towards reconciliation and mutual understanding. In the beginning Tillers, without intending to, found himself at the heart of a controversy over the difference that was and still is located in some forms of Aboriginal art. Over time he developed a collaborative relationship with Aboriginal artists and at the same time Aboriginal art became incorporated more fully into Australian art discourse. In Tillers’ own terms, Australian art had moved from a pre-Aboriginal art phase to a post-Aboriginal one. It is worthwhile developing this argument before challenging some of the grounds on which it is based. In incorporating Michael Jagamara Nelson’s Five dreamings 1982 as one of the main images within his The nine shots 1985, Tillers opened himself up to accusations of appropriating Aboriginal imagery without permission and impinging on the moral rights of the artist. The offence was compounded by the very ‘placedness’ of Aboriginal art, its apparent inseparability from locality. Aboriginal art was in place and Tillers’ art apparently challenged identities based on locality, removed images from their cultural contexts, and juxtaposed them with images from other places and times. After all, the very title – ‘Locality fails’ – of his reflexive critique of contemporary art, almost his manifesto, written in 1982 can be taken as a challenge to Aboriginal art or at least to some people’s hope for Aboriginal art: ‘The widespread though largely unstated hope (or even belief) in an “indigenous” Australian art ignores’, the logic of the postmodern world.1 The nine shots eventually brought about Gordon Bennett’s powerful riposte The nine ricochets 1990, which in turn borrowed images from Tillers. Much has been written about the apparent dialogue between the two works, often directed to explaining why they are different ethically and art historically.2 However, I believe that the fundamental significance of Bennett’s work must be understood in its own terms – in the multiple references it makes and interpretative possibilities it opens up – of which the dialogue with Tillers is only a small though important part. If there is a simple message it is that all that has happened in the recent history of Australia has been made possible by the colonisation and often the deaths of Aboriginal Australians; a message that in the 1980s and 1990s did appear to be getting across to large sectors of Australian society – the idea that there was a wrong that needed to be acknowledged and addressed. It was a message about appropriation, pain and alienation. It made the point, to paraphrase George Orwell, that the human condition is the same for all but more the same for some than for others. Over the next decade Tillers’ engagement with Aboriginal art continued to develop but it did so in an environment in which artists came into dialogue with one another across the racial divide. Tillers developed a personal relationship with Michael Jagamara Nelson, whose work he had originally incorporated into his own without permission. Working together in Brisbane as part of the Campfire Group, they produced collaborative works such as Nature speaks: Y (possum dreaming) 2001, based on iconic motifs from the Walbiri inventory of graphic signs. Two of these signs – for lightning and for possum – were subsequently included as recurrent elements in Tillers’ Nature speaks series.3 Permission was granted and collaboration acknowledged. Tillers’ inclusion of Aboriginal elements in his work seems to have become more explicitly a celebration of their aesthetic power. Aboriginal art had become something that was impossible to ignore in Australian art. We can even see Tillers’ art become increasingly based in locality as he comes to be at home in the Monaro – a conclusion Tillers teasingly draws us towards in titling an article on his recent work ‘When locality prevails’.4 If Tillers’ art has become post-Aboriginal, in the sense of referencing a component of Australian art that is no longer possible to ignore, does this mean almost by definition that it has become more Aboriginal?5 However, it remains an open question as to whether Aboriginal art is treated differently from non-Aboriginal art in his work. In general there has been no change in his practice of using images by other artists as components of his own work, but it could be concluded that the moral issues of treating Aboriginal artworks in the same way has become more cloudy, perhaps less vital. This progressivist view has its problems, even if at times Tillers nods in its direction. While there has been some progress – Aboriginal art has gained greater recognition over the duration of these developments in his art, and permission is often sought from Aboriginal artists before their work is used – the analysis I have presented both contradicts the spirit of Tillers’ art and could give the impression that the various issues have been resolved. Acceptance of such an analysis could indeed result in a taming of Aboriginal art, a forgetting of its impact by gently incorporating it within the mainstream, by making it part of the repetitive mantra that has been the avant-garde. It could be part of a process of recreating such a mainstream, which of course in many ways is what Tillers’ art has succeeded in overturning.6 The success of Aboriginal art almost offended many non-Indigenous artists. Its success as contemporary art was a shock because it apparently broke all of the rules. It came from outside the academy, from people who were outside contemporary art discourse, who did not play to the rules of the game and indeed did not know that there were any rules. The danger is that the progressivist history normalises Aboriginal art and makes it part of the discourse of contemporary Australian art without changing. It concludes that once we start talking to one another and become part of the same market, we become part of a global ecumene. Tiller’s conception of postmodernity had as a central theme the breaking up of and breaking out of rigid categories rather than the creation of a hybrid global avant-garde. It disrupted the temporal sequencing of art as much as it challenged locality. Indeed, it had been the linking of the spatial and temporal in an artificial and limiting evolutionary sequence that had become so deadening, culminating in the increasingly narrow yet ever changing contemporary avant-garde. Tillers recognised the diversity of world art practice and the fact that in many cases the contemporary avant-garde had been anticipated, both in the forms and in the kinds of practices that came under the rubric of art making. For example, it could be reasonably argued that the artists of Central Australia who incorporated sand sculptures within their ceremonies were substantively as much performance artists or installation artists as European artists who intervened in analogous ways.7 They were not the same as the performance artists of the contemporary west – context makes a difference to meaning, culture and history affect experience, and the intentions may be very different – but as expressive forms and as modes of action these art practices had much more in common than had previously been allowed. The categories of the modernist-oriented Eurocentric art world failed to allow for the appreciation and creation of meaningful dialogues with artists of other places and times, because they positioned them out of the present. The makers of sand sculptures were ritual experts, the designs they produced were sacred emblems, the hollow log coffins were functional objects – if a category had to be found for them they could be placed in the generic categories of craft and of ‘primitive’ art. They were not contemporary fine art. The categories that created limits on what the contemporary western artist could produce also limited the ways in which other arts could be viewed. In essence, this categorisation failed to recognise art making as a form of action that enhanced the agency of human beings, enabling them to do things that they could not do by other means. In contrast, the perspective that Tillers adopts enables Indigenous art to be part of a global history of art making that is not easily bounded in space and time, and is certainly not neatly divided into small, self-contained, easily grasped units of limited duration. And yet because art making has always been connected to contexts and purposes, the particular works do have their differences and are not all the same kinds of things, even though they have much in common. Art can be made as a religious icon, to embellish a building, as a regal tribute, as a political intervention, as a challenge to authority. When placed in another context – taken out of a cathedral and placed in an art gallery, taken from the dining table and placed in a display case, taken from a political protest and placed in a private collection – its original significance may be diminished or even contradicted. It simply is not the case that every contradiction can be resolved or that every difference is of equivalent value. The excitement and controversies generated by and over Aboriginal art as it entered Australian art discourse in the 1970s and 1980s concerned issues of real difference. It involved people taking bold and dangerous steps, often without knowing the ultimate consequences or the trajectories that the art – While ‘borrowing from’, ‘being influenced by’, ‘finding inspiration in’, ‘learning from’, and ‘building upon’ other people’s artworks is always going to be an integral part of art practice, it is never going to be without its dangers since art is not limited to particular kinds of objects. It is the case that some Aboriginal art produced for sale is sacred art; it is the case that under Aboriginal law the rights to produce those works might be limited to a small group of individuals; it is the case that the rights in such works might be vested in a group; it is the case that the breach of rights in and the unauthorised use of such artworks can be seen as a form of sacrilege that affects the fabric of the artist’s society. This does not mean that the works concerned are not artworks. It means, as has been the case throughout human history, that a work of art can be other things besides itself – in the case of some Aboriginal art it is a mark of identity, a title deed to land, a sign or instance of ancestral presence.8 However, it is important not to essentialise Aboriginal art, since at every place where it is produced it has its differences. The boundaries between different categories of object are often blurred and it is not always going to be clear what kind of work something is, or even how many different things it is. Aboriginal art is part of a dialogue with other Australian art; it is dynamic, changing, and responsive to different concerns, audiences and markets. As Aboriginal art becomes more visible and more integral to Australian art, an awareness of the subtle boundaries not to cross becomes more apparent, but the process of the inclusion of Aboriginal art in world art is always going to be complex, abounding in what may be irresolvable contradictions. Given the nature of Tillers’ work, the exclusion of Aboriginal motifs would have been as remarkable as any inclusion and just as subject to controversy. Tillers’ canvasboard system – the thousands of boards that he sees as a knowledge archive – is in many respects analogous to an artist’s notebook and the invisibility of Aboriginal art in that notebook would have made a statement. Indeed, Tillers is quite explicit in his inclusion of Aboriginal art in positive terms, acknowledging its importance and its significant intervention in the history of Australian art, which ironically allows Australian art to refocus on landscape and the history of place. Tillers has seldom been explicit about his reasons for selecting particular images for inclusion in his work; his use of the word knowledge is an interesting choice. But it seems that both qualities of form and significances of content are factors at play in his choices. Emily Kam Ngwarray’s Big yam dreaming 1995 is a case in point. Tillers writes ‘While Ngwarray’s majestic painting relates to the lifecycle of the yam my interest in it apart from its stunning beauty was that her image with its network of tangled lines and worldly unpredictable trajectories seemed like an analogue for the complex networked connections within my canvasboard system.’9 There is a view that in Tillers’ work, particularly early on, the meaning of the borrowed work has played a lesser role in its selection than formal attributes. Even if this were once true, it has increasingly been less so.10 Certainly context is part of meaning and Tillers’ whole approach involves recontextualising, but not in a way that denies the significance the images have in other contexts. His work is not concerned with the historic specificity of the motifs used, but content is a strong motive for their selection. No one can look at works or series of works with titles such as Diaspora 1992, Nature speaks: BC 2003, Outback: E2004, Local knowledge 2005 or Terra incognita 2005, without forming an impression that they may refer to or even cohere around important personal, historical or cultural themes. And yet at the same time the work is constructed to challenge contained meanings. The canvasboard system as a whole comprises the thousands of individual boards that are an archive of creativity, that have the potential to be reorganised into different sets. The sequences of boards and the panelled sets that are made from them present an emergent ordering. Parts of the sets are relatively more fixed than others, but the viewer is always conscious that the potential for reordering and reinterpretation was there from the beginning. As Tillers himself writes: ‘While the existing body of work (which is also a body of knowledge) determines to some degree what comes next, there is always within this system openness to chance, to serendipity, to coincidence and the possibility of new directions and unexpected interventions.’11 For Tillers art is both ‘a solitary journey of introspection’ and ‘above all, “a way of knowing”’.12 The works that are produced provide the opportunity for others to enter into the artist’s world, and to engage and respond to it, inevitably influenced by the artist’s own structuring of the information, but empowered to chart their own pathways and to form their own mental sets. Taking Tillers’ lead in responding to his inclusion of Aboriginal motifs in his recent work, my intellectual response to Terra incognita 2005 begins with an awareness of a series of disjunctions. Terra incognita follows on from the series of works that relocate Tillers’ painting in the Australian landscape, coinciding with his family’s move to Cooma in 1998. In many of these works, such as Mexico, etcetera 2001, place names appear or emerge – at times they seem to be floating beneath the surface of the painting, and at others they seem almost stamped onto it. The works pick up on the power of place names and their capacity to evoke memories and make connections. The names are chosen for that same combination of form and content that images are selected: the ‘readymade’ poetry of Coober Pedy, Kunanurra, Broken Hill and Faraway Bay; the salience of names in the Snowy Mountains to Australian history, his wife and her family; and many other, often serendipitous, connections. Many of the names already contained the transformed poetry of Indigenous Australia; they are names that existed for generations before the coming of Europeans, words from peoples whose lands, languages and lives were taken from them. In the midst of his ‘unfinished journey’ Tillers encountered David Horton’s map of Aboriginal tribal or language group names and began to include them in works such as Outback: A 2005. The names themselves provide a challenge to the idea of Australia as terra nullius and terra incognita, signifying the underlying presence of Indigenous Australians in the landscape. Matters of scale and of divisibility and indivisibility lie at the heart of the canvasboard system. Tillers’ compositions can range from isolated bits of partly recorded information piled up in stacks, to windows that provide views of a world outside, to towering walls that dominate the viewer – as in the case of Izkliede 1994 – or great vistas of unfolding landscape. Terra incognita is one such landscape, encompassing Australia as a whole. It represents a great scroll that unfurls Tillers’ iconography across Australia and imprints a particular image of history that simultaneously masks and reveals the diversity that lies beneath the surface. The painting is structured around a central motif of waves – waves that seem to be urged forward by the powerful image of the Grim Reaper, arriving in skeletal form on horseback from the top left-hand corner (geographically the north-west).13 The Aboriginal place names are distributed across the surface, roughly corresponding to their actual geographical location within the continent. Ngwarray’s Big yam dreaming forms the ground of the painting – it is represented strongly in its own right in one segment, and is barely visible in other sections. The modulated, ochre colour scheme of the panels, channelled with white and with occasional strong, black, burnt lines, evokes the desert landscape but also makes the whole strongly reminiscent of works by Rosalie Gascoigne. There are many tempting and competing readings of the painting – the waves of Aboriginal people arriving, or the waves of European invasion or, much more prosaically, a dry sunburnt continent surrounded by oceans. Ngwarray’spainting represents the generations of Aboriginal presence across Australia, it becomes part of the waves of history that wash the shores and extend into the desert lands of the Centre – a presence that shines brightly and fades as generations replace one another. An immense tragedy lies at the heart: the Grim Reaper that affects us all, the European colonist who brought death to the Aboriginal inhabitants and ultimately death to himself. Yet in the southeast corner of the continent, we read the slogan ‘we have decided not to die’. The tragedy is there but also the great beauty reflected in the colours, in the intricate entanglements of the yam roots. Perhaps it is the dry, dusty, burnt country of the Centre that is pushing out rather than the waves of the coastal waters that are pushing in. There is both dislocation and relocation in Ngwarray’sswirling design as it weaves its way across Australia. From one perspective this is can be seen as a reflection, indeed an exemplification of the European imaginary – Australia as the sunburnt country, Aboriginal people being the same everywhere. On the other hand, the encompassing nature of Ngwarray’sdesign possibly reflects the unity of Aboriginal Australia. The replication of her designs across Australia ironically raises precisely that problem of similarity and difference, ‘the same but different’, that characterises much discourse about Aboriginal art and Indigenous identity. Tillers de-regionalises Indigenous art in a way that runs counter to the way Aboriginal art is generally exhibited and written about.14 Wherever one looks at geographically emplaced names from Horton’s map – Tiwi, Gagudju, Yolngu, Yidin, Warlpiri, Kamilaroi15 – underlying it is a design by Ngwarray, an Alyawarre woman. No Pukumani poles, no x-ray kangaroos, no geometric clan designs, no bicornual baskets, no circle–line designs, no incised shields. The nature of Tillers’ art – its open-ended sequences and beginnings without ends – almost licenses one’s imagination to think about how it could have been different, what choices have been made, what ideas rejected. It is possible to imagine a very different way of mapping art onto place, in a painting broken into regional segments that together form a palimpsest of diversity. And if one goes back to Tillers’ earlier work, to the great wall of Izkliede and other works in the Diaspora series that are almost violently broken into segments, creating regions within the paintings, it is easy to see how Tillers might have constructed a landscape that was less unified and much more profligate in its borrowings. Tillers’ work has opened up in his mind, and potentially in the mind of the viewer, relationships across Australian art that have the effect of eliding categorical differences and emphasising synergies. In the case of Ngwarray he notes formal similarities with abstract expressionism, he is aware of the work’s relationship to landscape and he acknowledges it as a contemporary artwork. He does so without placing the image in a closed, interpretative box. He sees his work as part of a continuing trajectory of landscape painting – a tradition that has been extended and transformed by the intervention of Aboriginal art. The looseness of the categories created by Tillers’ oeuvre – their provisional nature, the fact that they continually reflect back and that they acknowledge repetition – opens up quite different ways of looking at the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal art as forms of artistic practice. They encourage us to look for synergies rather than forcing them into the same stylistic boxes – synergies at the level of artistic practice. If we acknowledge that Aboriginal art produced in remote Australia today is contemporary Australian art, then we must be open to finding similarities between the artists who produce it and artists working in other traditions that demand different distinctions and methodologies. We must avoid drawing simple stylistic analogies that force Aboriginal art into pigeonholes derived from western art history – expressionist, minimalist and so – or gleefully finding in Aboriginal art attributes that we associate with the avant-garde: Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri paints with acrylics and John Mawurndjul is an individual who breaks with tradition. It is those time-based, culture-bound criteria that have pigeonholed Aboriginal art as ‘other’ and failed to recognise its own genius and dynamic, but which at a more general level have also failed to recognise what Indigenous artists have in common with non-Indigenous artists. Over recent years I have on many occasions been forced to reflect on the relationship between the two artists whose works I have recently looked at more than any others: Imants Tillers and Narritjin Maymuru, the Yolngu artist who died in 1982. I am always struck by the similarities between their corpuses as much as by the differences. Certainly at one level the differences are profound. Narritjin saw his art as an ancestral inheritance, rights in certain design forms were restricted, he downplayed his own creativity and at times talked as if each painting he produced was a replica of previous members of a set. Yet that impression was often the product of the kind of questions he was asked and the way his answers were interpreted, and did not reflect what he was communicating through his art. Yolngu, strikingly like Tillers, see art as a form of knowledge. Within the constraints of clan and moiety Narritjin’s corpus is characterised by its diversity.16 The meaning of his art is centrally conveyed through the connections between elements, and connections outside the paintings to the world in which he lived. His paintings were divided into series associated with place, elements were repeated over time but usually with variations and differences of scale – as Tillers writes of his own work: ‘the series appears to proceed like an algorithm’.17 Although he guided interpretations in certain directions meaning was never exhausted, the series of paintings was never finished and meaning was ultimately open-ended. There are considerable synergies between Narritjin’s art practice and that of Tillers. The important way forward in deepening understanding of the diversity of world art is to break out of culture-bound categories and look at the relationships between artists’ work in terms of their practice and intentionality, not privileging the intention to produce something categorised as a work of art but viewing art more broadly as a means of acting in the world. The nature of Tillers’ art practice is such that it is always looking in two directions: externally to the world of images – to the body of knowledge contained within it – and internally as an expression of his own reflective journey. The canvasboard system represents a continuing dialogue between these levels of reality in a process that engages with the work of other artists in different places and times, yet makes them part of a contemporary dialogue. The works encourage the viewer to reflect on differences and similarities, to engage in the conversation by adding their knowledge and experience, even to challenge some of the inclusions and juxtapositions – and in doing so to enter into the world of affecting images that Tillers’ art creates. Howard Morphy 1 Imants Tillers, ‘Locality fails’, Art & Text, no. 6, 1982, p. 54. This point is made by Ian McLean in the introduction to his forthcoming book How the Aborigines stole the idea of contemporary art, and I employ his phraseology. |

| NGA Home | Introduction | Themes | Search | Essays | Learning | Visiting | Previous |