|

|

|

||||

|

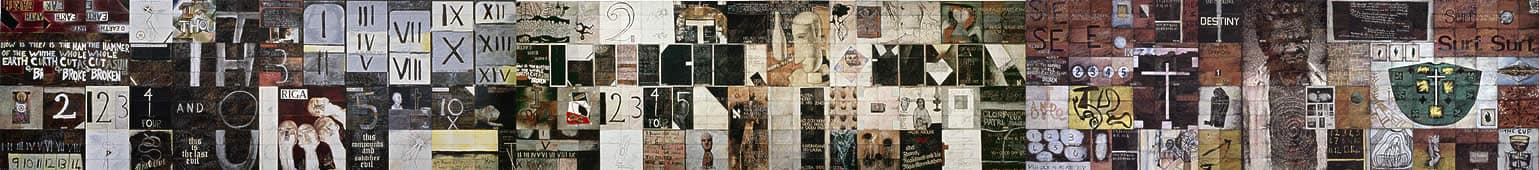

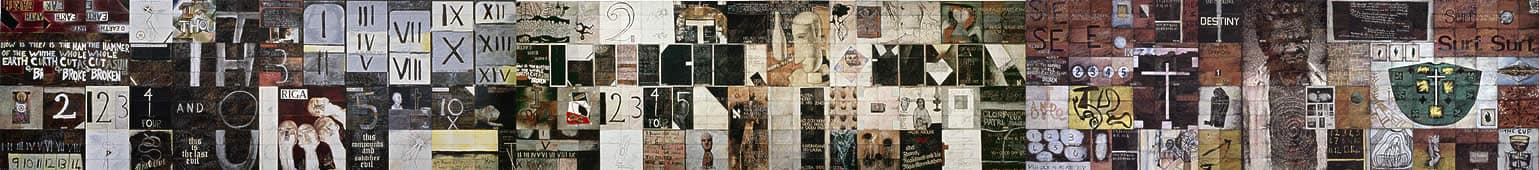

Biographical notes In the twenty-year period covered by this exhibition, Imants Tillers has lived and/or worked in three distinctly different studios: a home studio located on the foreshores of Little Sirius Cove in Sydney’s Mosman; a top-floor warehouse in inner-city Chippendale; and the current studio – located in the family home, Blairgowrie – situated 400 kilometres south of Sydney on the outskirts of Cooma, in the foothills of the Snowy Mountains. While the shifting conditions and dramatic developments of the local and global art scenes have had a direct and well-documented impact on Tillers’ art practice, the physical constraints of each studio – and the aspects of ordinary, everyday existence specific to each – have also played their part in contributing to the unique processes that form his distinctive style. Little Sirius Cove 1981–88 Tillers at the entrance to the exhibition Imants Tillers: paintings for Venice at the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 1986 By 1984 Tillers was well established in an airy, four-roomed flat in Little Sirius Cove in Sydney. In the ensuing period, he not only consolidated his variations on the One Painting series1 , but also commenced his first tentative experiments with painting on canvasboard that soon precipitated the outpouring of images that later became the Book of Power – now numbering nearly 80 000 panels. This momentous breakthrough resulted in a major reorientation in his work. It is important to convey the excitement of the moment, as well as the quantum leap in Tillers’ practice, as the all-encompassing canvasboard system took shape. It was here that most of the iconic works of the 1980s were produced – works thatwere instrumental in establishing Tillers’ reputation and international profile long before their significance was fully recognised in Australia. Our rented flat had a veranda facing east across Sirius Cove to Curlew Camp, home to the Antipodean Bohemians. Throughout the 1890s Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts and others had lived there in tents, painting plein-air scenes of the surrounding Sydney Harbour foreshores. Streeton and Roberts painted on drapers’ boards – thin, wooden panels with bevelled edges. Their reasons for using these were similar to Tillers’: they were both portable and economical. Day and night, summer and winter, we virtually lived on the Mosman veranda and our daily lives were saturated with this view. It was not, however, until after we had left Sirius Cove in 1988 that Tillers painted View 1989, his own version of Roberts’ painting The camp, Sirius Cove 1899, superimposed with numerals from Colin McCahon’s Numbers 1966. The spare bedroom of our flat, measuring only 3.5 x 5.0 metres, served as Tillers’ studio. With his work desk positioned in the bay window, crammed between filing cabinets, shelves and overflowing boxes stacked with art materials, Tillers looked onto a steep flight of stone steps that were carved into the moist sandstone cliff. Over sixty steps led up to the street at the top of the hill and provided our only access. Thus it was the sheer practicality, versatility and portability of the canvasboard that lent itself to exploitation at a time when Tillers was becoming increasingly disenchanted with working on the large-scale canvases of the One painting series. The very first canvasboard works were simply hundreds of pencil and charcoal drawings on individual 25 x 38 centimetre modules. The first forty-nine of these were then experimentally arranged in a grid to form the rudimentary Suppressed imagery I in November 1981. In stamping the numbers 1 to 49 on the front of each of the canvasboards Tillers was initiating the process that continues today, whereby each canvasboard and the paintings they form becomes part of a larger, ever-expanding whole, moving (in his own words) relentlessly ‘towards infinity – an impossible goal’.2 These experiments with pencil and charcoal on canvasboard continued throughout 1982, alongside the many variations and ‘ventilations’ of the series.It was not until September, however, that the first major composite canvasboard works with a single image emerged, with The field 1982 and Island of the dead 1982 both rendered in charcoal on 100 canvasboards. Tillers exhibited Island of the dead and one of the first painted images, White Aborigines I 1983, at Matt’s Gallery in London for his first international solo show. In an extraordinary demonstration of the international possibilities of the canvasboard, he dispatched the entire exhibition by ordinary airmail, packed in two small cardboard boxes. Tillers on the veranda at Sirius Cove, 1987 The canvasboards were soon established as a highly efficient means of producing paintings on a monumental scale within a cramped studio space, and the process of assembling and de-assembling, stacking and unstacking, installing and de-installing became integral to the development of the canvasboard system. The images in the paintings were generated by Tillers’ ongoing quasi-scientific research utilising the art books and journals in his rapidly expanding library. In the early 1980s the flow of opportunities to exhibit internationally increased. By the time John Kaldor approached Tillers for inclusion in his major assault on the New York art scene, An Australian accent: three artists – Mike Parr, Imants Tillers and Ken Unsworth to be held at PS1, New York, in April 1984, Tillers had already represented Australia at the XIII São Paulo Bienal (with George Baldessin), had shown in Eureka! Artists from Australia in London, and had been Australia’s inaugural representative (with John Nixon) at Documenta 7 in Kassel, Germany. While the exhibitions in London had drawn critical acclaim, it was the experience at Documenta 7 that had the most profound effect on Tillers. Given only one month to select and prepare his exhibit for this prestigious international survey of advanced contemporary art, Tillers nominated a new variation of an existing work: Two paintings, hidden from view 1982. Tillers’ involvement in Documenta 7 highlighted for him the marginality of Australian art within the international scene. He resolved to take on the challenge of addressing the so-called provincialism problem3 , and within the next two to three years had conceived and produced a totally new body of work that would launch him successfully onto the international scene. Locally, there was increasing visibility and a deepening appreciation of his work. It was at about this time that Tillers began to write extensively and published three key articles in Art & Text: ‘Locality fails’ 1982, ‘Fear of texture’ 1983 and ‘In perpetual mourning’ 1984. These writings formed the intellectual basis for his new trajectory and were ‘defining moments in Australian post-modernism’, still widely discussed and much quoted in art-historical discourse today.4 A flurry of intense activity throughout 1983 and early 1984 also produced a dozen monumental finger paintings on canvasboard for inclusion in An Australian accent. These new paintings were exhibited with an additional six or eight paintings installed as stacks. In a lengthy analysis of the exhibition, published in the New Criterion, Eric Gibson was particularly taken with these stacks, describing them as a ‘truly original idea’ relating to the work of Jasper Johns and Marcel Duchamp.5 On his increasingly frequent trips to Europe and America, Tillers had developed a keen awareness of trends and developments in the international avant-garde, which he followed assiduously in art journals. He was particularly attracted to the expressionist movement sweeping the art world at the time – notably the new Italians, the so-called trans avant-garde, and the German neo-expressionists. The expressionist thread in his own work had an obvious resonance with this new painting movement, and he could not have anticipated that An Australian accent would be selected to be presented with Expressions: new art from Germany at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC, as a double bill featuring extreme new work by Germany’s foremost neo-expressionist painters. Returning from New York and Washington, An Australian accent began an Australian tour. In October 1984 Tillers showed with his new dealer, Bess Cutler Gallery, in New York. This was a watershed exhibition, being Tillers’ first commercial solo show in New York and only his second solo show outside Australia. It received surprising attention, with reviews in the New York Times, Artforum, Art News and Art in America, and had been timed to coincide with the second major museum show of Australian art in New York: Australian visions, at the Guggenheim. In his review of the latter exhibition for Art News, Ken Sofer wrote:

Isidore in Tillers’ studio at Sirius Cove, 1986 Perhaps the most interesting painter in town recently was Imants Tillers … These paintings are seething stews of borrowed images, putting Tillers in the company of such diverse contemporary practitioners as Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Thomas Lawson, Mike Bidlo and Sherrie Levine … But these paintings are, in fact, provocative and vigorous statements of great wit.6 However, leading critic Donald Kuspit, writing in Art and America, was so scathing that Bess wrote to Tillers, saying ‘he attacks so strongly that you should be flattered’. Within the same month Rapture 1983 was shown with Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Richard Artschwager and others in a group show called Synthetic art at Harm Bouckaert Gallery in New York. Rapture was described in the catalogue as ‘maybe the most radical piece in the show for its quotation (Borofsky) is so recent’. In June 1985 – soon after the birth of our first daughter, Isidore – Tillers learnt that he had been selected to represent Australia at the 42nd Venice Biennale the following year. It was the first time a single artist had been chosen to do so. In November that year Tillers’ second solo show at Bess Cutler opened. It was anticipated with great curiosity and generated a good deal of interest. Tillers’ strategy of speaking directly to his New York audience from the Antipodes with borrowed images they’d recognise was surprisingly successful. New York Times critic John Russell wrote: ‘Well-remembered from his appearance in last year’s Australian show at PS1 Imants Tillers is still dismantling the acknowledged masters of twentieth-century art and putting them together in ways that are partly admiring and partly ironical.’7 The nine shots 1985 was the centrepiece of the show, the first of several major but controversial paintings utilising German neo-expressionist artist Georg Baselitz’s Ein Neue Typ figures together with Aboriginal central desert dot paintings. In this case, fragments from a Michael Jagamara Nelson painting were interwoven with the Baselitz figure. Amongst the artists who streamed through the exhibition were Jiri Georg Dokoupil, Julian Schnabel, Philip Taaffe, Mike Bidlo, Sherrie Levine, Arakawa and Madeleine Gins – all no doubt curious to see how Tillers had reworked his borrowings from their works. The remainder of 1985 and the first few months of 1986 were largely spent painting new work for Venice. Mount Analogue, Heart of the wood and I am the door were all completed in 1985, and Psychic (for Yves Klein), The Kondratiev wave and The hyperborean and the speluncar followed soon after in 1986. At that time Australia had no national pavilion in the Giardini, so the Australian exhibit was installed in the Corderie of the Arsenale. Despite this less-than-perfect setting, Tillers’ work was noticed and reviewed, which led to expressions of interest from several major commercial European galleries. Susan Wyss, based in Zurich, invited him to show the next year. The most remarkable response was written by Michael Newman in British Artscribe, who singled out Tillers as one of the five highlights of the Biennale, praising his work along with that of Daniel Buren, Sigmar Polke (who won the Golden Lion award that year), Frank Auerbach and Christian Boltanski. He described Tillers as giving appropriation ‘an interesting twist both technically and semantically … the semantic twist is that Tillers represents appropriation as the second-handedness of provincial culture’.8 The paintings for Venice toured several Australian venues, receiving enormous coverage in local newspapers – most positive, some positively glowing and one very negative one, in the Melbourne Age, criticising Tillers’ application of paint. With the intensification of interest in Tillers’ practice both locally and abroad, and the escalating commitments this generated, it became clear that he needed assistance. I elected to sell my business and commenced work at home at the start of 1987.We then began looking for a larger, more suitable studio for us to share with Alec Tzannes and Wendy Lewin, who were also in the process of relocating their architectural practice. Later in 1987 we purchased a three-storey warehouse in Myrtle Street, Chippendale. In addition to his exhibition commitments, Tillers was heavily involved in the first of several collaborations with Tzannes. His artwork for the interior of the dome of the new Federation Pavilion was fabricated in vitreous enamel on canvasboard-sized steel panels. Tillers travelled to New York for his third solo show at Bess Cutler, to Zurich for his first solo show with Galerie Susan Wyss and to London to finalise a list of works for the major ten-year survey that Iwona Blazwick, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), was planning for 1988. The Bess Cutler show was again well received and much reviewed in the art press. In Portland, Oregon, Reed College mounted a solo survey of current work, titled Imants Tillers: Australian appropriations. Of the many significant group exhibitions in 1987, two were particularly noteworthy: Howard Fox’s landmark survey Avant-garde in the eighties, at the Los Angeles County Museum, and Sandy Nairne’s State of the art: ideas and images in the 1980s, at the ICA in London (accompanied by a book and television documentary). Fox’s exhibition later registered in Artforum’s ‘40th anniversary issue: the 1980s’, which gave a comprehensive listing of the most significant international shows of that decade. Tillers had exhibited in four of these. By the end of 1987 Tillers had not only outgrown the constraints of the small home studio but we as a family had also outgrown the four-roomed flat. We moved nearby to a converted Victorian duplex. A remarkable transformation had taken place during our time at this picturesque spot – from a perceived position of disadvantage as an Australian artist always on the margins of the global art world, Tillers had become one of ‘Australia’s most internationally successful contemporary artists’.9 Myrtle Street, Chippendale 1988–96 Imants and I moved into the new studio in Myrtle Street in mid 1988. The windows running the length of the building faced north, with views over the treetops of the park to the city skyline, and to the west there were glimpses of the Gothic towers of the University of Sydney. The constant play of light on the internal walls from reflections of the mirrored city skyscrapers was later captured in Telepathic music 1994. Initially Tillers continued to work in exactly the same manner as he had at Sirius Cove, utilising the same desk, the same chair and the same canvasboard module. The attractions of the canvasboard system prevailed despite a vast increase in his workspace – or perhaps because of it. The generous floor space, measuring 10 x 25 metres, meant that he could be working on several pieces at any one time and experimenting with even larger formats and new materials. Consequently, oilstick was used extensively, with large paintings laid out on the floor to dry. For the first time, the walls were long enough to accommodate several major works for simultaneous display. Productivity increased exponentially.

Isidore in her Latvian national costume, 1993 With the architectural offices downstairs we had ready access to a sophisticated photocopying machine. This opened up fresh possibilities for Tillers, enabling the reproduction of texts, and later images, from his own paintings for use as templates for subsequent works. By transferring text onto canvasboard with photocopied, handmade templates, then using a scalpel to carve around the letters or images, Tillers was able to superimpose many layers of paint, text and image to create the intricate interlaces and surface complexities of what was to become his idiosyncratic painting style. While Isidore was at preschool in the mornings during 1988 and 1989, Imants and I would work together in the studio. In the afternoons she would join us, playing with her Lego, painting and drawing, and practising shaping her letters and numerals. She also took to drawing freehand grids, mimicking the processes she saw her father employing. Inherited absolute 1992 incorporates some of her drawings into a layer that floats alongside a borrowed Giorgio de Chirico family scene. Our years at Myrtle Street were marked by significant upheaval and reorientation, determined largely by two major global events: the Wall Street crash and the collapse of the Soviet Union. In 1987 when the American stock market crashed, the repercussions sent the art world into recession and all but wiped out the Euro–American art market. Galerie Susan Wyss folded in 1989 and Bess Cutler closed in 1991, soon after Tillers’ fourth solo show with her, leaving him without representation in Europe or America. Meanwhile, in Sydney, Yuill/Crowley was experiencing severe financial difficulties. The disintegration of the Soviet Union held personal significance for Tillers as a child of Latvian émigrés. Emboldened by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, two million Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians staged the Baltic Way, a peaceful demonstration for independence by joining hands to form a continuous human chain across the three Baltic States. Then, in September 1991 – the week that our second daughter, Saskia, was born – Latvia boldly declared independence from the Soviet Union. After fifty-one years of forced incorporation into the USSR, Latvia was a free country for the first time in Tillers’ lifetime.10 Like the previous year, 1988 was very busy. The high point was undoubtedly the ten-year survey at the ICA: Imants Tillers: works 1978–1988. It was not only the first substantial attempt to present Tillers’ work in depth but one of the first major shows of any living Australian artist to be held at a significant international institution. The exhibition catalogue carried a text by Michael Newman and was the first deeply informed, analytical discussion of Tillers’ artistic output. The exhibition and its British tour provided unprecedented exposure for Tillers’ work, yet passed virtually unnoticed in Australia. The long-term repercussions were significant, with Tillers’ inclusion in Phaidon’s ubiquitous publication The 20th century art book, documenting ‘the most innovative contemporary artists from Monet and Picasso to the present’, and in The Oxford history of western art.11 In the latter, the entry on Australian art singles out Tillers as having found an escape from the ‘1970s crisis in painting … through his challenging and ironic post-modernism’.12 In the same year, the first of three avant-garde readymade portraits by Tillers was hung in the popular, but essentially conservative, Archibald Prize. Portrait of Paul Cox 1988 was one of a series of radical Superscan-generated paintings executed in collaboration with Marianne Baillieu. The striking resemblance to Paul Cox was entirely coincidental, having been recognised only after completion of the work. Other notable group exhibitions in Australia that Tillers participated in that year were the major bicentennial survey Creating Australia: 200 years of art 1788–1988and the Australian Biennale; internationally, his paintings toured Japan in Edge to edge: Australian contemporary art to Japan. He was also included in several American exhibitions, including Redux: Michael Bidlo, Sherrie Levine, Doug Huebler, Philip Taaffe, Richard Pettibone, Imants Tillers in Los Angeles. Another major survey in a public gallery was held in 1989: Imants Tillers: 19301 or as of October at the National Art Gallery, Wellington. The New Zealanders were very receptive to the work and Peter McLeavey Gallery took on representation of Tillers’ work. Solo shows that year, in New York and Sydney, were held at Bess Cutler and Yuill/Crowley, with most of the work based on images by Colin McCahon. The latter prompted a scathing response from Christopher Allen in the Sydney Morning Herald, who remarked that ‘these appropriation games have become simply boring’.13 However, Allen must have revised his opinion some time later before writing his book Art in Australia: from colonisation to postmodernism, where he covers Tillers’ approach in depth, citing him as ‘the most important and representative of postmodern artists in Australia.’14 Tillers’ portrait My wife as an apparition 1989 was selected for the Archibald in December that year and was unexpectedly a major contender for the prize.15 Edmund Capon commented that ‘if there was any controversy to be had, it would be in the trustees picking an avant-garde work by painter Imants Tillers’.16 In his review, John McDonald claimed that ‘Tillers has superimposed his wife’s features on a rather feeble drawing room painting of a lady in full Victorian regalia then blown up the image to wall sized proportions.’17 Tillers responded: ‘I have not added my wife’s features – they were already present in Isobel Tweddle’s original Portrait of Miss Ivy Ball in fancy dress. This uncanny resemblance was pointed out to me in 1972 by Julie Ewington. Using Marcel Duchamp’s principle of readymades, I have waited 17 years for the right moment in which to inscribe this image as a readymade.’18 Four of the five solo shows in 1990 were held in commercial galleries. The bridge of reversible destiny in Sydney was by far the most significant, consisting of a massive, stacked installation of as many past and present canvasboard paintings as Tillers could muster. With pieces also included in an astounding nineteen group shows that year, Tillers’ work was exhibited in such diverse locations as San Francisco, London, Brisbane, Nouméa, Montpellier, Adelaide, Jakarta, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Melbourne, Osaka, Sydney, Riga and Canberra. Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga, 1993 Wystan Curnow later noted that there was a shift in Tillers’ studio practice at this time19 , referring to the ‘action paintings’ Tillers had begun to produce. Attracted by the paradox of duplicating the chance configurations of drips and splatters of paint in Jackson Pollock’s late Black enamel paintings, Tillers deliberately chose a method that would exaggerate the differences between the originals and his own versions of them. He meticulously transferred Pollock’s abstract, gestural marks onto his masked painted panels using carbon paper and then painstakingly cut around each drip with a scalpel. This was the beginning of a process that has since developed into an integral part of his practice, utilising the scalpel, rather than the paintbrush, as a primary tool. Counter to the self-styled ‘anarchic eclecticism’ of his previous work, Tillers focused obstinately on Pollock for the next few years, obsessively reproducing about twenty of the American artist’s works. In fact, two of the three solo shows in 1991 exhibited these paintings exclusively. Group shows that year again numbered more than ten and Tillers entered the Archibald Prize for the third and last time in 1991, with another coincidental portrait: Necessary protection 1990. This portrait was of Murray Bail, a frequent studio visitor who had inadvertently photographed himself reflected in the glass of a framed work on paper by Colin McCahon. Tillers discovered this readymade portrait when Bail sent him the snapshot.20 Towards the end of the year Tillers travelled via Paris and the Cologne Art Fair to the newly independent Latvia. During a chance rendezvous in Paris with French critic Pierre Restany, he was encouraged to satisfy his curiosity about his parents’ homeland and urged to exhibit there, accepting the longstanding invitation to mount an exhibition at the Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga, in 1993. Tillers was approached later that year by Curnow, who wished to make him the subject of a comprehensive monograph. Curnow commenced extensive research on the first in-depth study of Tillers’ art practice and five years later, in 1997, Imants Tillers and the ‘Book of Power’ was published. Academic Graham Coulter-Smith also began ten years of intense research for his PhD, culminating in a second monograph The postmodern art of Imants Tillers: appropriation ‘en abyme’ 1971–2001.21 The most significant event in 1993 was unquestionably the realisation of the exhibition in Riga, with the new work Diaspora addressing themes of identity and displacement, representing a major turning point in Tillers’ art practice. Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Leon Paroissien, and Chief Curator Bernice Murphy made their resources available and co-published the small catalogue with Tillers. Built in 1905 and untouched during the decades of Soviet rule, the Latvian National Museum was obviously seriously under-resourced. On our arrival we were directed to the single crate containing the entire exhibition – 288 canvasboards that made up the Diaspora painting. The family installed the whole exhibition unaided. Isidore, aged seven, alternately assisted us with the Velcro dots and entertaining her baby sister, Saskia. Nevertheless, the work was received with great enthusiasm and interest when the exhibition opened, gaining extensive coverage on national television and radio, and in the press. We then spent a couple of weeks touring Latvia to visit Imants’ mother’s surviving childhood friends and relatives. Many had endured incredible hardship and deprivation under the Russians, including deportation to Siberia for perceived crimes against the State. The extraordinarily picturesque countryside had remained virtually unchanged in fifty years, unmarked by progress.While there we explored the possibility of reclaiming confiscated family properties and perhaps establishing a studio in Riga but Imants was struck by the recognition that he didn’t belong there – he was not Latvian at all. In fact, he was Australian.

Saskia, Imants, Isidore and Jennifer at Mosman, just before moving to Cooma, 1996 After three months in Europe Tillers had a solo show at Peter McLeavey’s gallery in Wellington and soon after was astounded to discover that he had been awarded the Grand Prize of ten million yen at the second Osaka Painting Triennale in Japan, with his expansive Pollock-based painting A portrait and a dream 1991. The family travelled to Osaka for the opening formalities and award presentation, and then on to Kyoto, where we were struck by the exquisite beauty of the local Zen temple precincts and formal raked gardens in their full autumnal glory. Many group shows in 1993 included Tillers’ works, the most significant being Identities: art from Australia at the Taiwan Museum of Art in Taipei, and 1994 was dominated by more than a dozen local and international group exhibitions. Director of the Pori Art Museum in Finland, Marketta Seppälä, was keen to collaborate on an expanded version of the Riga exhibition revolving around Diaspora. Preparation for Diaspora in context: connections in a fragmented world commenced, as did work on the two monographic studies of Tillers’ work involving intensive consultation with both authors. In Sydney Tillers held his inaugural solo show with his new dealer, Sherman Galleries in Paddington. Having completed Izkliede1994, the sequel to Diaspora 1992, Tillers began work on Paradiso, which he completed late in the year, forming what he then termed the Diaspora trilogy. He began a parallel series of smaller, though still substantial, 120-panel works addressing the same themes and following the same format. In late 1994 Tillers travelled to Washington, DC, to install Izkliedein curator Julia Robinson’s Antipodean currents at the Kennedy Centre. The following year the family travelled to New York for the second American venue, the Guggenheim Museum in New York. We then flew directly over the North Pole to Finland for the installation of Diaspora in context at the Pori Art Museum. Seppälä had drawn together as many of the original sources in Tillers’ Diaspora as possible – including several major McCahons, a Georg Baselitz and a Nicholas Roerich. John McDonald, who travelled to Finland to see the exhibition, reviewed the show in depth, concluding that ‘with the theme of exile and displacement … [Tillers] has touched on one of the leitmotifs of the twentieth century … through the most coolly postmodern of means, Tillers is moving towards an aesthetic of redemption’.22 The exhibition was later shown at the MCA in Sydney and toured New Zealand. By the mid 1990s the euphoria and optimism of the 1980s had begun to wear off as the repercussions of the stock market crash were still being felt. Despite Tillers’ incredible productivity and international profile throughout this period of recession, the reduced visibility resulting from the closure or demise of so many of his local and international dealers found us in a precarious situation, burdened with unexpectedly high overheads and declining sales. Interest in Tillers’ work within Australia shifted as curators and critics began to focus on post-colonialism. When at the start of 1996 we were unexpectedly offered a property in the country, we surprised ourselves and everyone we knew by accepting. Cooma presented a welcome escape. A year of anticipation followed, dominated by the mammoth task of reorganising our lives for the move. It was also a year of relentless international travel for Tillers, as exhibition commitments didn’t abate. It was in Amsterdam that he became acquainted with the work of Philipp Otto Runge, in an exhibition pairing him with Caspar David Friedrich. Runge’s cherubim found their way into Tillers’ work later that year and have been a dominant and enduring source ever since. He travelled to New Zealand for the final installation of Diaspora in context and at the same time held a solo show in Auckland. In June he travelled again to Amsterdam, this time for the installation of Diaspora in an international group exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum. The world over/under Capricorn was shown simultaneously in Wellington and Amsterdam. Back in Australia Tillers painted the fourth work in the Diaspora series, Farewell to reason 1996, for inclusion in an exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, also featuring Rosalie Gascoigne and Rover Thomas. In September Tillers travelled to Seoul for the third Asian venue of System’s end: contemporary art in Australia. Late in 1996 Tillers was informed that he had been awarded the Bronze Prize in the Osaka Triennale. He travelled to Japan to collect the prize and took the opportunity to visit Arakawa and Madeleine Gins’ Site of reversible destiny at Gifu, returning just two weeks before we left Sydney for Cooma on 20 December. He noted that we were moving towards our own site of reversible destiny and referred to Blairgowrie as his new ‘twelve-acre studio’. Blairgowrie 1996 – the present Tillers and Saskia in his studio at Myrtle Street, Chippendale, 1996 The move to Cooma had come completely out of the blue! It was an unpremeditated, intuitive and irrational response to a letter that arrived in the mail unannounced and uninvited, asking if we were interested in purchasing the property Blairgowrie. In a moment of surprising synchronicity the letter had come to us at precisely the point in time – perhaps the only time – when we happened to be receptive to the idea of moving away from Sydney. The family’s response was an immediate ‘Why not?’ and Tillers rationalised the move by declaring that the ‘radically new setting’ would enable him to begin a new series of works expressing an engagement with locality, with landscape. As Howard Morphy has observed: Art gives meaning to place and takes meaning from place … The Monaro has, through art, become part of [Tillers’] life, and through his art the Monaro has become connected to the world outside in a particular way.23 On arrival we were surprised to discover a hitherto unknown connection with the Monaro – my paternal great-great-grandfather Farquhar Mackenzie had settled there in February 1837, some 160 years earlier.24 Built in the 1880s, Blairgowrie was a charming, yet dilapidated weatherboard farmhouse set within established European gardens containing a scatter of original outbuildings, and surrounded by twelve acres of bushland. The house itself was built for Ann Litchfield, eldest daughter of grazier James Litchfield, when she married Arthur Balmain. The property backs onto Ngarigo Lambie Gorge, the spectacular but little-known natural feature that has recently been nominated as a place of Aboriginal significance. Totally overgrown and forlorn, the terraced gardens, gravelled circular drive and ancient established trees of the property exuded a profound tranquillity and powerful spirit of place. Restoration presented an enormous challenge, yet Blairgowrie also offered autonomy, freedom from the distractions and obligations of the art world, and the possibility of creating a family home after the constraints of fifteen years of shared accommodation and workplace partnerships. Besides, Tillers was immediately excited by the opportunity to exchange Sydney’s subtropical climate for the distinct four seasons of an inland mountain climate with similarities to that of his parents’ homeland: the birch forests and pines, the winter snows, the wild mushrooms in the autumn. As Tillers wrote some years later: ‘Here in the garden at “Blairgowrie”, nature speaks in the Latvian vernacular of my childhood’.25 Within a week of arriving at Blairgowrie, Tillers had rejected his original idea of using the huge shed on the property, built in the early 1900s, as a studio. He instead installed himself in the largest room of the house where, nine years later, he continues to work productively. Once again, he placed the same work desk and chair in the large, north-facing window, looking directly into the garden; French doors on the south side open to a stonewalled courtyard and the old orchard beyond, and the installation of bookshelves soon provided a home for Tillers’ most essential resource: his library. With a floor area of almost fifty square metres and ceilings high enough to accommodate the modest fifty-four-panel canvasboard paintings that have become the preferred format, this light-filled garden room fulfills its purpose more than adequately. Working in a space such as this has influenced Tillers’ practice in very particular ways and has led to subtle refinements in technique. As the bedrooms open off the studio, he has been restricted to fast-drying acrylic paint that allows for the stacking of work in progress at the end of each day. In turn, his family life has sometimes intruded into the Book of Power. For example, recent works have incorporated computer-generated characters discovered by Saskia whilst sharing the studio to complete her homework. This set of symbols appears frequently in the Nature speaks, Blossoming and Outback series. Isidore’s studies have also found their way into the work, as in the image of Templar Knights wearing Ned Kelly helmets in Blossoming 3 2004, sourced from research for her cultural history essay on chivalry.26

The attractor 2001 sculptural installation, steel and stone components Olympic Park, Homebush Bay, Sydney

Since settling at Blairgowrie Tillers has continued to exhibit extensively, with solo and group exhibitions held throughout Australia and abroad. His work has been seen in such places as the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, Finland, Spain, Mexico, China, Japan and Southeast Asia. However, the difficulties of reconnecting with Sydney presented a new obstacle for Tillers. Being a non-driver he was faced with long hours in transit, as the region is poorly served by public transport. A positive outcome of this time lost from his studio practice was the evolution of his travel journal, with its notes and observations, into something productive – Daily Research. This diary of visual and textual occurrences, ideas and inspiration for new works, and gleanings from his current reading matter has been conducted relentlessly since September 1998 and is an undirected, non-goal-oriented process. It now numbers over two thousand pages and has come to replace his sketches and studies for new works. In 1997 Philipp Otto Runge’s cherubim heralded a new direction in the Enigma of arrival series, which culminated in the fifth Diaspora-scaled work, Monaro 1998. In 1998 Tillers began recording the local geographical place names, which later found their way into paintings such as the Nature speaks series. Late that year the family travelled to Mexico City, where Tillers was the sole representative for Oceania in a large exhibition titled Five continents and a city. He showed The bridge of reversible destiny, sending the entire contents of the studio for the installation of a fourth version of this constantly evolving work. The largest and most comprehensive survey of Tillers’ work to date was mounted in 1999 in Monterrey, Mexico, and was curated by Charles Merewether for the Museum of Contemporary Art (MARCO): Towards infinity: works by Imants Tillers. The exhibition displayed thirty-five major works and covered twenty-five years of his artistic career. After settling on the Monaro and having become familiar with this particular inland landscape, Tillers became receptive to further exploration of the great Australian interior. In 2000 he traversed Australia, from the southeastern corner to the northwestern tip, in a light plane and later visited Uluru for the first time. He also travelled to Singapore for the group exhibition The rose crossing; his painting Rosa mutabilis 1998 was inexplicably lost at the conclusion of the tour. In December that year Tillers was honoured to be appointed a trustee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, commencing his first three-year term in 2001. He was a Visiting Fellow at the Southampton Institute in the United Kingdom that year, where he met artist Maurice Owen, commissioning editor for Graham Coulter-Smith’s book. Much of the year was spent overseeing the fabrication of Tillers’ two major sculpture commissions with Alec Tzannes, for the Olympic Park at Homebush Bay in Sydney: The attractor, a twenty-five-metre high steel ladder, and Eight women. During this period Tillers began a series of collaborations with Michael Jagamara Nelson through Michael Eather’s Campfire Group; the works were later exhibited at the Fire-Works Gallery in Brisbane. At this time Empathy, the show Tillers had co-curated with Marketta Seppälä, opened in the newly expanded museum in Pori. The exhibition showcased works by New York based, Latvian-born artist Vija Celmins and seminal conceptualist Robert Barry, along with works by British artist Susan Hiller, Australian James Darling and New Zealander Shane Cotton, among others. In October Tillers was awarded the Silver Prize at the Osaka Triennale, thus completing a winning trifecta – he had now received gold, silver and bronze. In 2002 Australia was the focus country at ARCO, the international art fair held annually in Madrid. Tillers showed Caja negra 2001, depicting a burnt and blackened Kosciuszko landscape, an eerie premonition of the catastrophic bushfires that were to devastate Thredbo and vast tracts of the Kosciuszko National Park and suburbs of Canberra. While the painting was on display in Madrid, we were preparing to evacuate as the bushfires threatened Cooma. Curator Charles Merewether installing Spirit of place at Monterrey, 1999 In 2002 Tillers travelled to Germany for his inclusion in Kunst nach Kunst [Art after art], held at the Neues Museum Weserburg in Bremen. This landmark show, which focused on appropriation, included works by Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, Carl Andre, Art & Language, Robert Rauschenberg and Sigmar Polke. Tillers’ floor-piece, Carl Andre in Delft 1987, was displayed together with the Polke it had referenced and the Andre that Polke had satirised. In 2003 Mexico, etcetera (the sixth of the Diaspora-scale works, originally painted for inclusion in Empathy) was exhibited with Izkliede at the First Beijing International Art Biennale – Mexico, etcetera won the inaugural Prize for Excellence. As the drought set in at the start of 2003, and the impact of the bushfires of the previous year was felt, Cooma–Monaro was declared a natural disaster area. The bush began to wither and die, and Blairgowrie was ravaged by desperate wildlife driven from the bush into the garden. By 2004, however, the garden was beginning to show signs of recovery. Tillers’ new series of paintings, Blossoming, drew on the garden directly for inspiration and followed the Outback series of 2003. The local volunteer-run Raglan Gallery held a very successful fundraising exhibition of Tillers’ work, Local knowledge, in support of the initiative to establish a Cooma–Monaro regional gallery. His solo show at Sherman Galleries in October 2005 presented the Blossoming and Outbackseries, reflecting the unresolved tension Tillers continues to feel between the European and the Australian. The seventh monumental Diaspora-sized painting, Terra incognita, was completed mid year for Imants Tillers: one world many visions and its sequel, Terra negata (the eighth in the sequence), was completed at the end of November for inclusion in the fifteenth Biennale of Sydney, Zones of contact, in 2006. In the same year Tillers was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of New South Wales, in recognition of ‘his long and distinguished contribution to the field of the arts’. Living on the Monaro has given Tillers the authentic connection with the Australian landscape that he has long sought. Writing almost a decade after moving from Sydney, he observed: ‘issues of locality and identity have been uppermost in my mind and have made their presence felt in my recent work, not just as literal representations of landscape, of the grass, hills, sky, clouds or rocks around me, but as “evocations”, through text and other layered visual elements’.27 Jennifer Slatyer 1 The One Painting series is based on a misregistered postcard of the Basilica of St Francis of Assisi. For full documentation of this series see One painting, cleaving, exhibition catalogue, Wollongong: Wollongong City Gallery, 1990. |

| NGA Home | Introduction | Themes | Search | Essays | Learning | Visiting | Previous |