|

|

|

||||

|

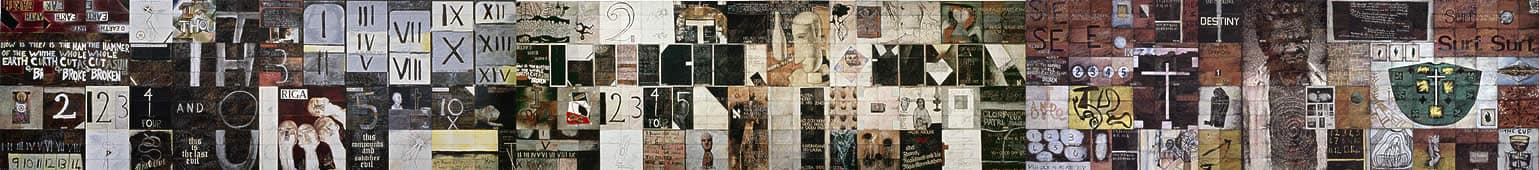

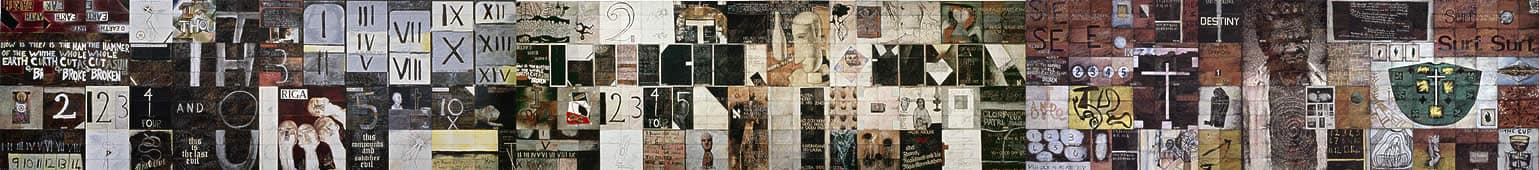

Tilling history This paper was presented at a forum to coincide with the exhibition Imants Tillers: land beyond goodbye at Sherman Galleries, Sydney, 29 October 2005. I speak off the record, outside the protocols and legitimising prose of our history books and those who seek to regulate the conduct of speech and reflection. This is not my native land but one of adoption from an early age. And while for many this matters little, for me this demand for adaptation has borne down strongly on my experience. As a child, we crisscrossed the country in my father’s car, and as I gazed from the back window, hearing my father speak of delicate lilac and yellow flowers blooming in the dry heat along the way, I would dream of the mist descending down the valley, yearn for the cool crisp air, and see before me the turbulent swelling waters of the sea. Perhaps, it was simply being jammed together with my two sisters in the back seat that provoked me to imagine myself elsewhere. Later too, as a young man, I travelled to different points within Australia and overland to the Centre and the Nullarbor Plain to find neither a sense of understanding nor a belonging or longing to return. When I did return to Australia, some eighteen months ago, I went to Canberra in the region nearby Imants and his family. Years had passed yet, still if not worse, it was difficult to adapt and learn to live in the landscape that surrounded me, for even while there was a sense of familiarity there remained within me a sense of perpetual estrangement. On occasion I visited the Tillers’ home, rushing headlong across the desolate suburbs of Canberra North, the barren sweep of Lake George, the grassy plains of Monaro and rolling hills of Cooma. But not once did I slow down, not once did I stop, to look. I endure the land, the land endures me. This is not either the landscape of Imants’ familial unconscious, a Riga whose skyline is defined by the steeples of its churches seen from across the riverbanks, a Latvia of small pockets of villages with smoke burning in cold winters, of long narrow roads cutting through the groves of trees and on, running down to meet the gentle waves lapping the shoreline of the Baltic Sea. There is a country where the harshness of wintry landscape is softened by the velvety layers of snow and silvery brown of the birch trees gleaming under the northern light. Travelling across this land, we are all guided by words composed of names of famous men from other places – a different lilt and intonation to the names of Phillip, Macquarie, McArthur, Jackson, Hume – men who had travelled far and stamped their enduring legacy, lest they be forgotten, in this distant land. Words and images that bespoke of a faraway England, another time and paintings made of a country that Different from any other landscape, Australia unfolds as vast stretches of dry land, a desolate beauty, the beauty of desolation. An unremitting outback, offering no remorse for the stranger who strays under its harsh midday sun. We learn to live here. Nothing to be seen so they said, a nullarbor the colonial boys had called it, a place where the immense canopy of the sky looms over the land. To look long enough is to experience a loss of control. We are no longer at the center, nor seems it sufficient to cast a surveyor’s eye that sweeps back and forth across the land, measuring the space guided by the horizon line. Rather, we are faced with the experience of the land tilting up into Perhaps the paintings of Imants have taught me otherwise, to see again. As Jennifer has recently said of his work, Imants’ paintings are not about depiction. They do not depict the landscape so much as speak to the landscape. This is not a landscape constructed out of minute observation, nor framed through an immersive experience of belonging to the land. Tillers’ response to the land is, at once, both more and less than visual. In this regard it responds to what William Kentridge observes in his essay ‘“Felix in exile.” Geography of memory’ (1994). He writes of the correspondence between a ‘terrain’s hiding of its own history’ and painting’s obliviousness ‘to its position in history’. In the paintings of Imants we are drawn into this landscape through a system of panels and fragments, an interplay of names and voices, a vertical layering of images. An unspoken history then except for the words of places, words for which the tongue has had to relearn its paces, turning and twisting in the mouth, words then spoken without knowledge of their meaning, the necessity and mantra of repetition. These are words written over and again as if, by virtue of their repetition, meaning will appear. Words floating, hovering above the scrubbiness of a ground, the scrub – as it is so fondly defined – that reminds me of the windowpanes of an airplane that has flown across the dry ground of the interior – a ground that veils evidence of another world, a kind of natural camouflage against the intensity of the gaze, images and words suppressed, unreadable, that can never be understood, fully grasped in their meaning or significance of their presence. Just there, lying in the ground, belonging to the ground. Does this place here, now, mark the beginning of what is in fact an ending, an ending within which there is nothing to be done except by virtue. Virtue of the fact that death prevails in the absence of nourishment as we build our gardens and walls around us, a laying down of foundations, sheltering us from the land, a procedure of domestication. Or will we be forever condemned to dwell outside the mansion of our dreams, the stranger, the ventriloquist, the object of translation fearful that, in the end, the incommensurate – the scrubby incoherence of the ground – and words that, haiku-like, tumble down before us, will leave us in a condition of unwilling suspension, hovering above the ground, reciting words in thin air, averting eyes to the fearful clarity of what it is before us, of where we stand, or a future in which we are destined to become ‘I am “I” who is becoming “I” who is not I’ (Haniya Yutaka). Images marking a space where there is no horizon, no horizon line, but simply, ever so simply, the dry infinite space that recedes towards an unknown, indeterminate sphere we name infinity. There is a blossoming. We till the soil, digging and raking the earth this way and that, seeking to unfold, fold and unfold again ‘the year in its successive states – blossoming, producing bearing, destroying’ (as Imants cites Philipp Otto Runge). We till until the harvest appears. The frailty of the blossoming tree stands brightly in the early morning light and again softly as the sun dips beyond the horizon line: a certain flow and ebb like the words we speak and are spoken. We till and till again in the desire to belong, we till as we would in speaking with another, of images and words, of surfaces, of the body as belonging to the earth and of the earth the body, as of women in certain lands of Africa who, on entering the vow of marriage with a man from another region, eat the earth in order to initiate the act of belonging. Here then the blossoming of intent, of an austere wish. We till because if we were to do otherwise, the melancholy that belongs to the frailty of our lives would return, not just the haunting of spirits in the air that mingle and mesh while, nonetheless, guiding over the course of our lives, but a trans-generational haunting, a legacy which is ours, that bespeaks of a terrible history of usurpation. To till is to nourish the successive stages that will allow the cycle of replenishment and renewal, of successive days bringing into light the eventual turning, like the sap that runs freely from the bark to be cut and transformed into the book of the Indigenous people. An act of repetition, of tilling, no longer the inconsolable desire that swells deeply within the folds of longing but of belonging to another, an other, no longer a derangement but an arrangement of sorts – ‘a throw of the dice that will never abolish chance’, yes, but ‘evidence too of a totality however meagre’, ‘I cannot breathe/do not leave me/Europe. Endless’ (Tillers, Blossoming 6 2005). Where, there, here before us, image embedded, to be lived with, words inscribed to be remembered and spoken: a double haunting. In the beginning that was itself an ending, Charles Merewether |

| NGA Home | Introduction | Themes | Search | Essays | Learning | Visiting | Previous |