Neo-Dada, Pop & Multiples

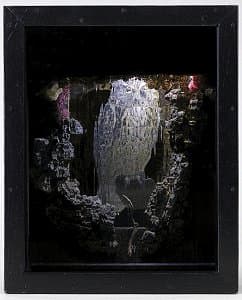

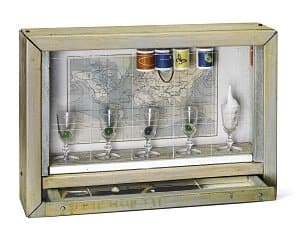

- Joseph Cornell

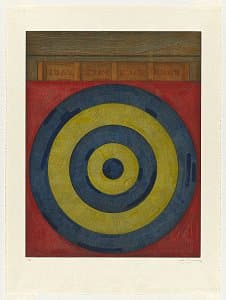

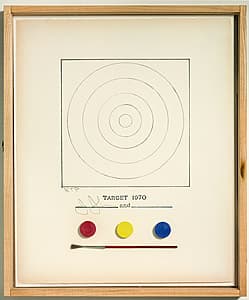

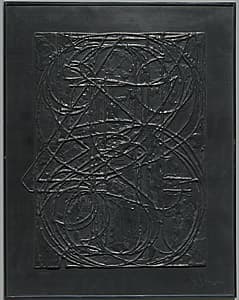

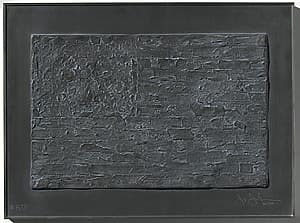

- Jasper Johns

- Edward Kienholz

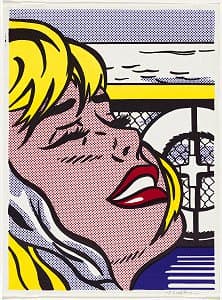

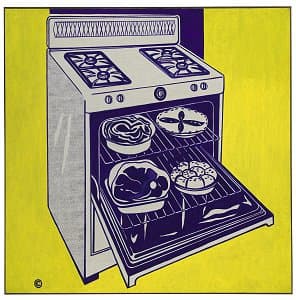

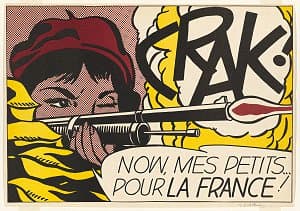

- Roy Lichtenstein

- Man Ray

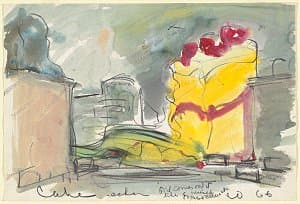

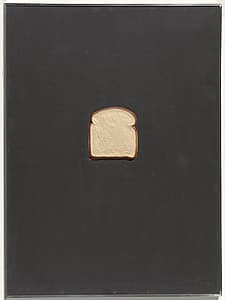

- Claes Oldenburg

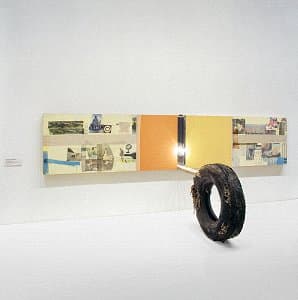

- Robert Rauschenberg

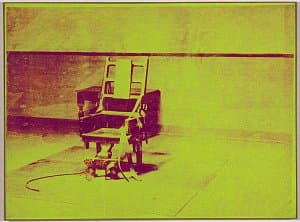

- Andy Warhol

Pop art is based on consumerist imagery and mass culture, rejecting distinctions between good and bad taste. The English critic Lawrence Alloway is credited with coining the term, which came into common usage in discussions by the Independent Group at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London in the 1950s. In 1957 artist Richard Hamilton defined Pop as ‘Popular (designed for a mass audience); Transient (short term solution); Expendable (easily forgotten); Low Cost; Mass Produced; Young (aimed at Youth); Witty; Sexy; Gimmicky; Glamorous; and Big Business’.[3] Pop was figurative and hard-edged, often using photographic techniques. At first exponents of Pop art were called Neo-Dada, because their use of commonplace objects and subjects suggested an affinity with Marcel Duchamp’s readymades.

By the early 1960s archetypal images shaped by American vernacular and contemporary mass culture were impossible to ignore. As well as creating works that reflect the prosperity of the postwar period, consumerism, technological prowess, commercialisation, conformism and the mass media, Pop artists hinted at less-celebrated aspects of American society―civil unrest, urban poverty and cold war tensions.

Pop art and the idea of the multiple, a three-dimensional object issued in an edition, coalesced to produce a natural embodiment of this art form. The idea of the multiple is predicated on the democratic ideal of making avant-garde art available to the widest possible audience, undermining the rarefied nature of the unique and ‘original’ work of art.

[3] Richard Hamilton, letter to Peter and Alison Smith of 16 January 1957, Collected words 1953–1982, Thames and Hudson, London, 1982, quoted in Steven Henry Madoff, Pop Art: A critical history, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1997, pp 5–6.