Conceptual

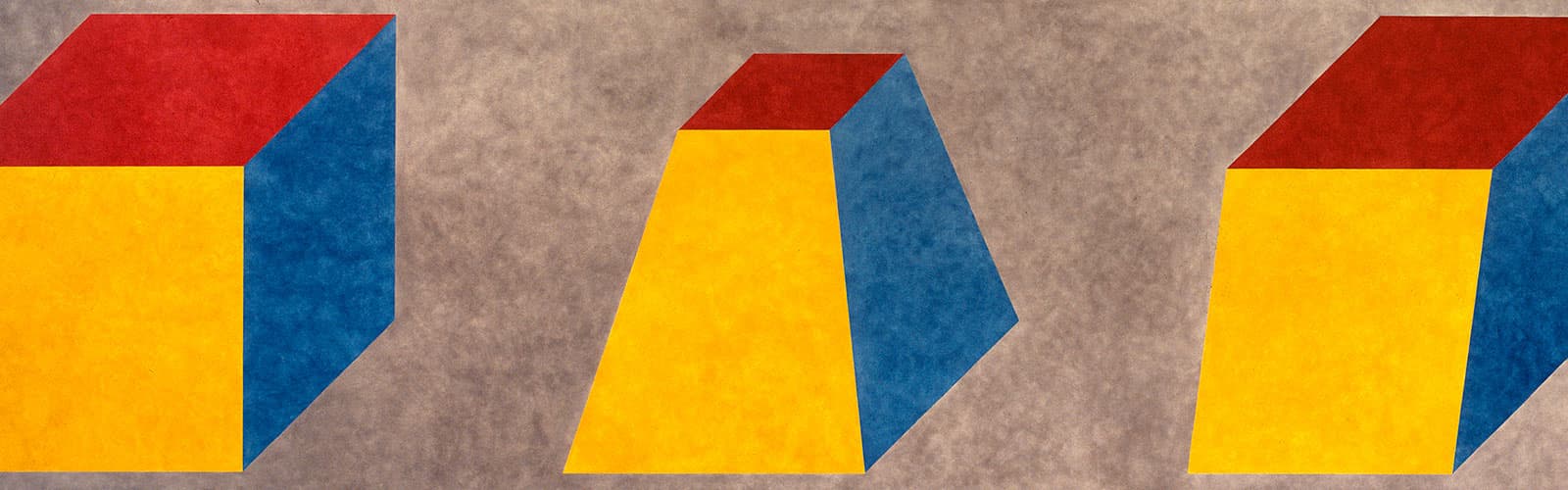

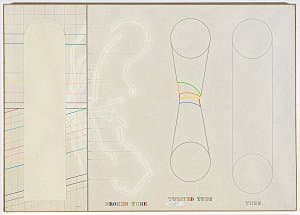

- Arakawa

- John Baldessari

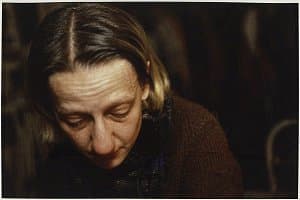

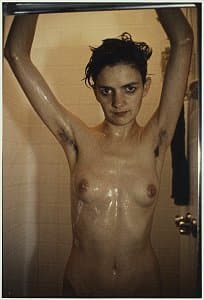

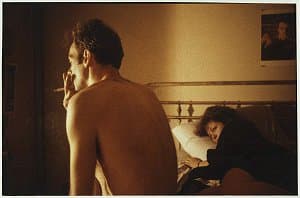

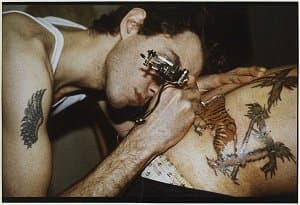

- Nan Goldin

- Joseph Kosuth

- Sol Lewitt

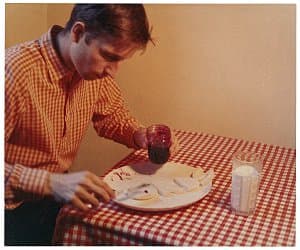

- Bruce Nauman

- Yoko Ono

- Joel Shapiro

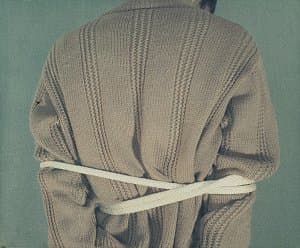

- Cindy Sherman

- Robert Wilson

Conceptual art has its origins in 1913 with Marcel Duchamp’s readymades. Rather than practising traditional disciplines such as painting and sculpture, a question is posed: what is art? The proposed answer of Dada artists in the First World War, and Conceptual artists from the 1960s onwards, is that art is anything made, or chosen, or even named, by an artist. The artist conceives a concept, an idea which predominates and is valued above aesthetic properties.

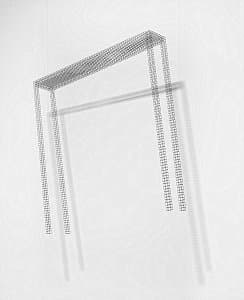

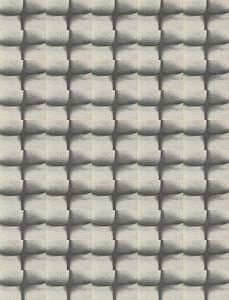

Neutral and cool in its presentation, the new movement appeared bland and unemotional. Some Conceptual artists added text to conventional media, or used text alone. Other works, particularly those using neon, employed stronger colours, but most Conceptual art made in the 1960s and early 1970s used black and white or drab shades of beige and grey. At its worst Conceptual art was arid and incomprehensible, at its best it was challenging, even liberating.

Conceptual artists took a highly critical approach to the art market and its mechanisms under Western capitalism, especially the gallery-dealer and auction house system of sales, as well as complicit collector-investors and art museums. The logical consequence was, therefore, to make unsaleable art, realised temporarily, or publicly and not-for-sale, or in multiple copies. Printing was the cheapest and most accessible, hence democratic, means of disseminating ideas, followed by photography. Print publishers also editioned small, inexpensive multiple sculptures, and the category of the artist’s book was invented. Documenting the process of Conceptual art in the making also allowed for sales of photographs, postcards and other records to make a living for the artist, apparently uncontaminated by the art market.