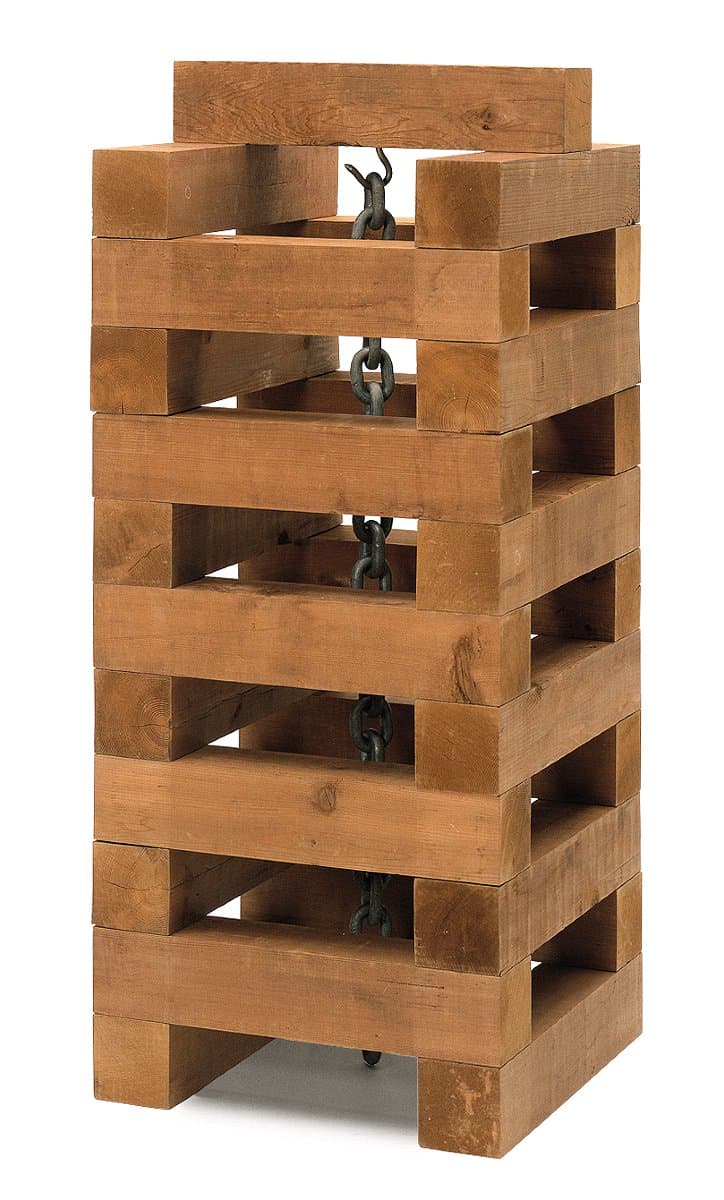

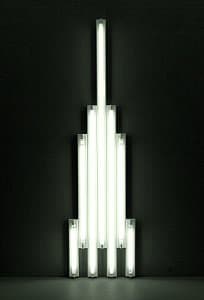

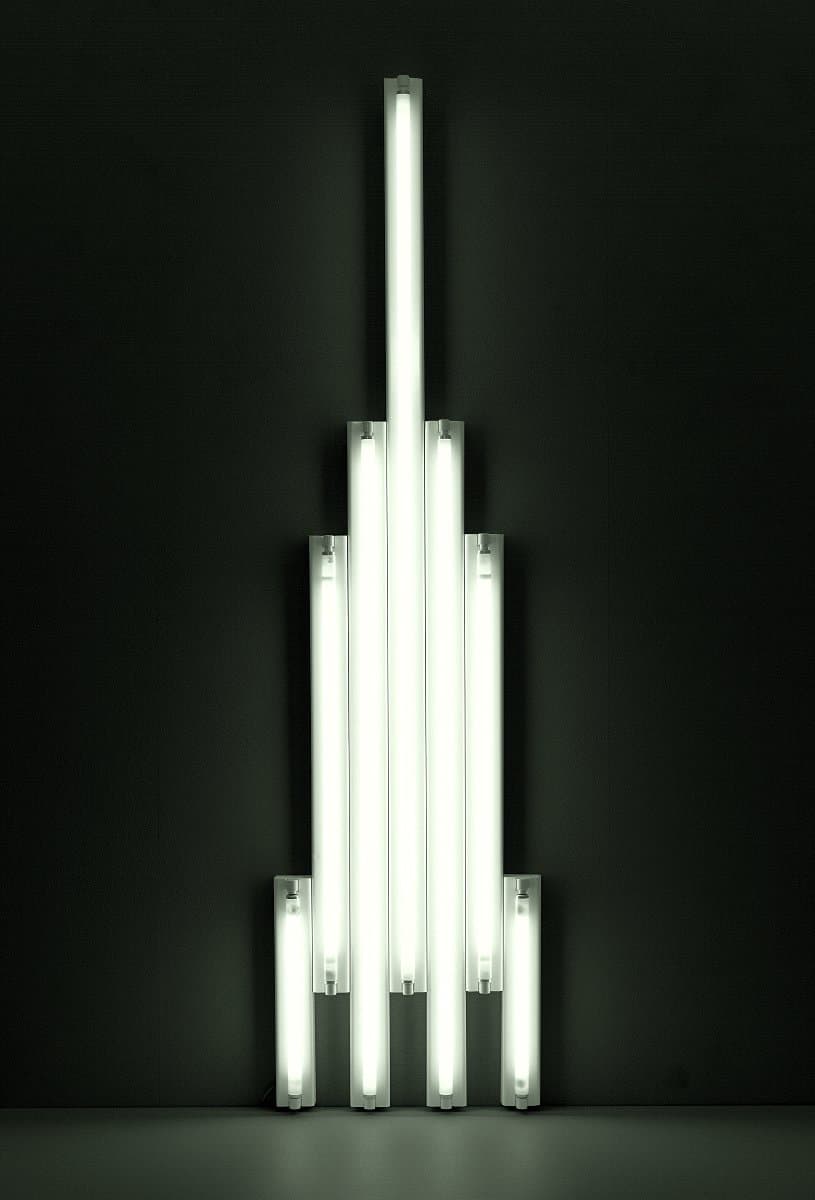

Barnett Newman

Learn moreBroken obelisk 1963/67 / 2005

© 2018 The Barnett Newman Foundation, New York/ARS, New York/Copyright Agency The Barnett Newman Foundation

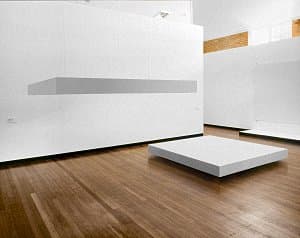

More detail | PermalinkBarnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk 1963/67 is powerfully symbolic and acutely political. The monumental sculpture combines the qualities of ancient forms with the geometry of modern architecture and materials. The genesis of the work is traceable through, and runs parallel to, Newman’s painting practice; it is, moreover, closely entwined with his small but impressive sculptural output. The artist’s first three-dimensional work, Here I 1950, forecasts the emphatic vertically of his forms while his final sculptures, Zim Zum I and Zim Zum II 1969, suggest mystic, all-enveloping spaces that expand beyond human scale towards the architectural.[1] Although Newman himself differentiated between the ‘planar’ and ‘volumetric’ problems of his work, he wanted both his paintings and sculpture to ‘give the onlooker a sense of place, a sense of being there’.[2]

Here I—comprising two slender wooden uprights, set into a mounded square base crate, covered with plaster—was shown at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, in 1951.[3] In 1962, after several hiatuses he returned to Here I, casting two bronze versions and making adaptions to the base. Ideas for his next sculptures developed quickly. For Here II 1965, made in weathering steel, three uprights of equal height, one thick and two thin, are set on truncated pyramids grouped on a base. Here III 1965–66, combining stainless and weathering steel, likewise suggests a logical progression, as if Newman decided to isolate and enlarge the central section of the preceding work.[4] Because the bases are elevated slightly, Here II and Here III both seem to hover. The emphasis on the relationship between upright form and its base is an idea that finds full articulation in Broken Obelisk, as Armin Zweite astutely observed: ‘An inverted obelisk, its shaft broken, is mounted on a pyramid in such a way that their tips touch and slightly penetrate each other—an upward-moving force meets a downward-sweeping movement, or, to put it another way, a vertical load is supported by an opposing thrust.’[5]

Broken Obelisk seems to have been influenced by several practical concerns. Initially, as Newman’s sketches show, the pyramid was flatter and more squat and the obelisk much thinner, so it appeared more precariously balanced. To develop its dimensions while retaining the teasing connection between the massive forms, he relied on Lippincott, a Connecticut fabricator specialising in working with artists to build large-scale sculpture. The monumentally of the final sculpture is, of course, key, and engineering drawings demonstrate how the pyramid became taller and the relationship between the obelisk and pyramid more elegant, with the two elements meeting in diagonal cross formation serving to highlight the upper broken end of the obelisk. A full-scale model, produced to test the spatial effects, confirmed the final configuration, and a second Broken Obelisk was fabricated. The works were installed in front of the Seagram Building in New York and adjacent to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington in October 1966. Broken Obelisk also developed a memorial quality as demonstrated by the third exemplar installed within the reflecting pool near the Rothko chapel for the Menil Collection in Houston and dedicated to the memory of Martin Luther King. As Newman commented, writing in the year of King’s death, ‘I hope I have transformed its tragic content into a glimpse of the sublime’.[6]

Lucina Ward

[1] Here I (Menil Collection, Houston), Zim Zum I (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) and Zim Zum II (Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf).

[2] Newman, as he stated in a 1966 interview with Washington Post critic Andrew Hudson, considered the elements of his practice quite separately: ‘I do not consider my sculpture to be a three-dimensional equivalent of my paintings. I think the problems are altogether different. Painting is a planar art. Sculpture involves for me the problem of volume. But I hope that both the sculpture and the painting give the onlooker a sense of place, a sense of being there’. Barnett Newman, Barnett Newman: Selected writings and interviews, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1992, p 273.

[3] The shaped and amorphous plaster surface of Here I, the edges of the upright elements in particular, prompted parallels between the sculpture and Newman’s painted ‘zips’.

[4] Both Here II 1965 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa and Davros Collection, Switzerland) and Here III 1965–66 (Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel and Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas) were produced with the Treitel-Gratz, a foundry on Long Island.

[5] Armin Zweite, Barnett Newman: Paintings, sculptures, works on paper, Hatje Cantz Publishers, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1999, p 269.

[6] Quoted in Harold Rosenberg, Barnett Newman, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1978, p 77.

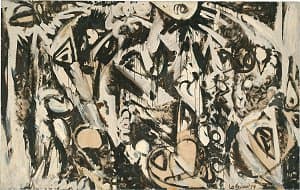

Jackson Pollock

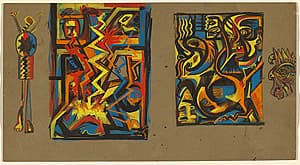

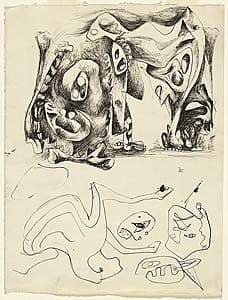

Learn moreUntitled c. 1933-39

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1986

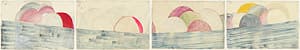

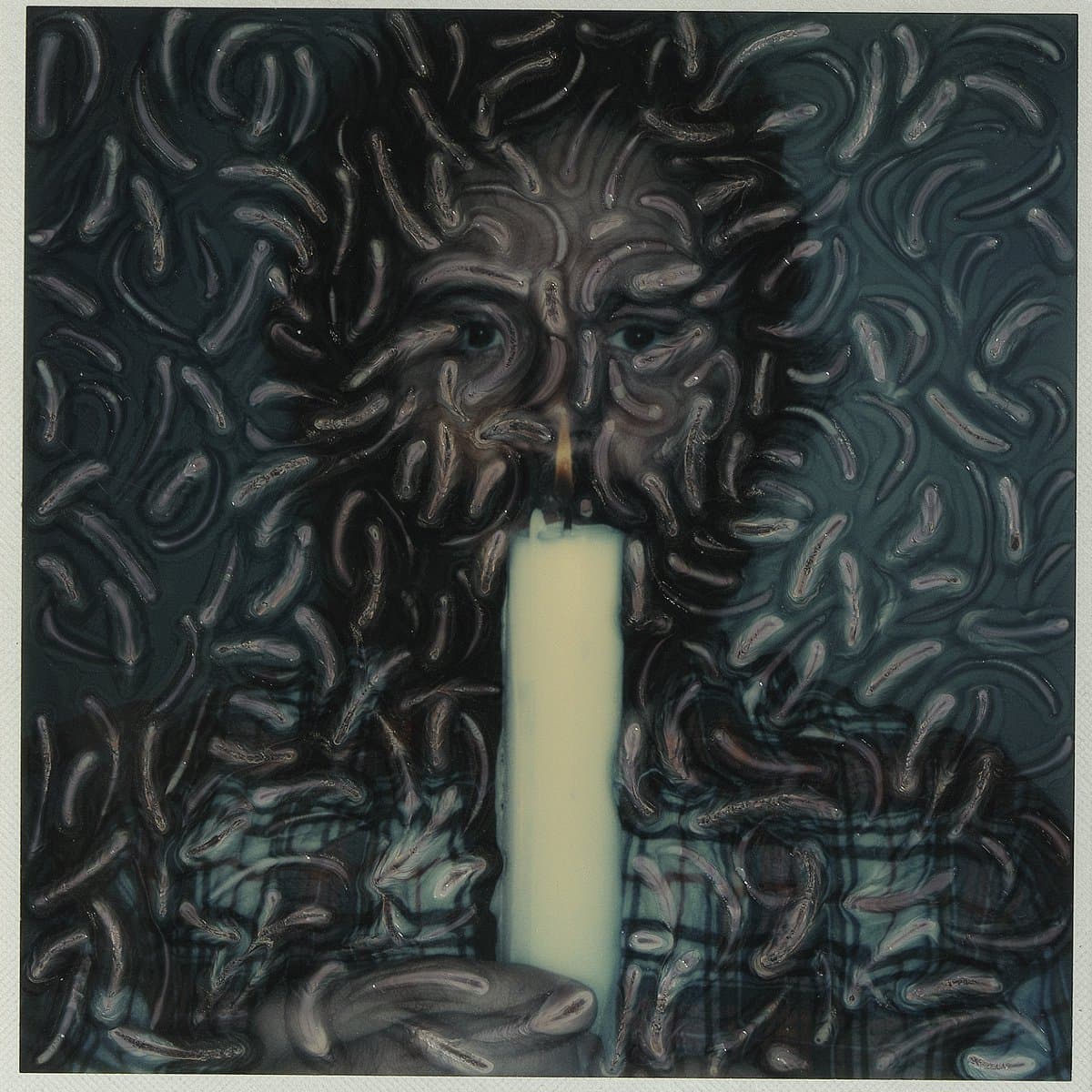

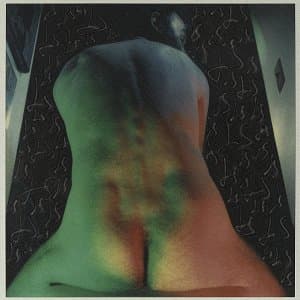

More detail | PermalinkJackson Pollock was a patient of the Jungian psychologist Joseph Henderson: a treatment that coincided with the artist’s growing interest in Surrealism, and a concurrence of events that resulted in a creative outpouring. Between 1938 and 1943, Pollock produced numerous pictographic drawings based on striking symbolic motifs, including a cache of 83 drawings provided to Henderson as material for analytical aids.

Works in the collection show a close association with such ‘psychoanalytic drawings’, both in style and subject matter. Untitled c#1933–39 is a dynamic composition depicted through a faceted, vertebral form. An amalgamated figure displays both horse- and bird-like features; a conjoining of two animals or an animal-human entity that occurs frequently in Pollock’s drawings of this period. In Jungian iconography, animals such as snakes, mandalas and shadows are symbolic referents for life forces such as birth, death, power and failure.

Jaklyn Babington

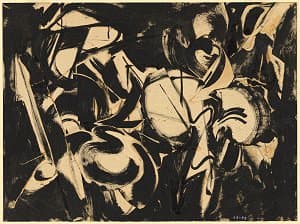

Jackson Pollock

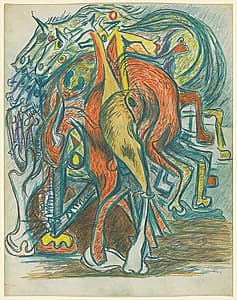

Learn moreUntitled c.1938-41

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1986

More detail | PermalinkJackson Pollock was a patient of the Jungian psychologist Joseph Henderson: a treatment that coincided with the artist’s growing interest in Surrealism, and a concurrence of events that resulted in a creative outpouring. Between 1938 and 1943, Pollock produced numerous pictographic drawings based on striking symbolic motifs, including a cache of 83 drawings provided to Henderson as material for analytical aids.

Jaklyn Babington

Jackson Pollock

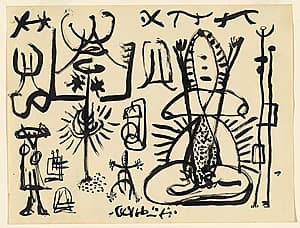

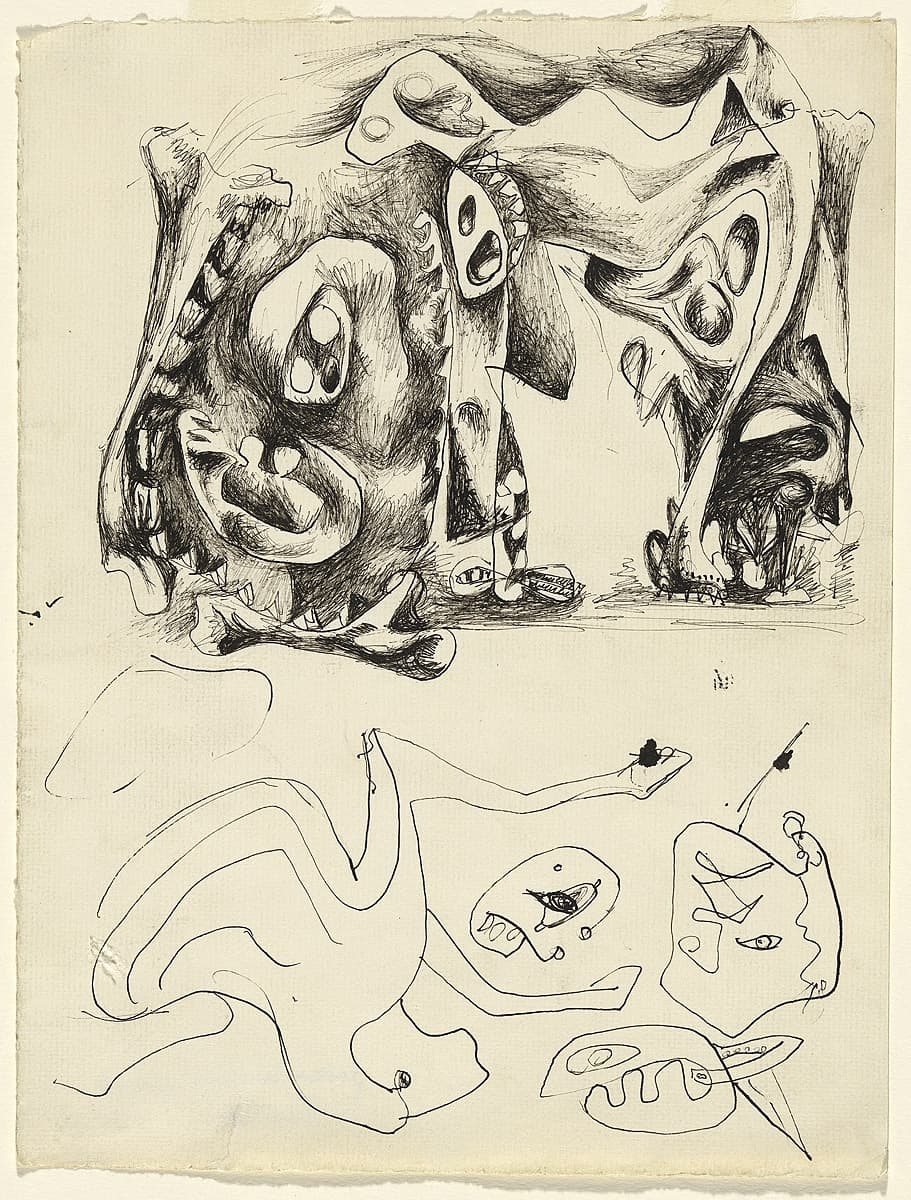

Learn moreUntitled c.1939-42

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1986

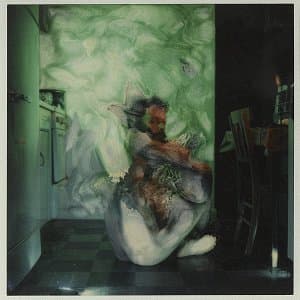

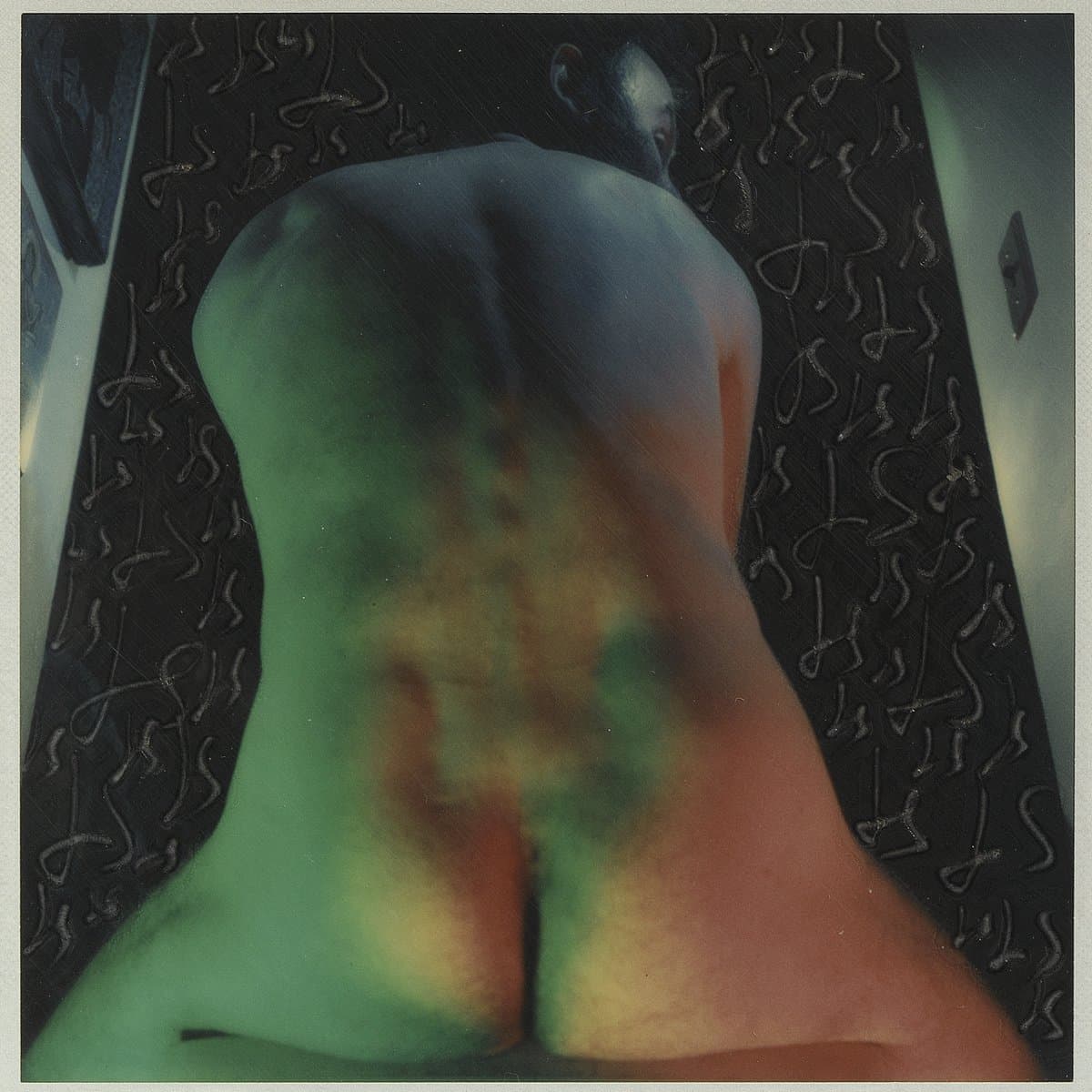

More detail | PermalinkJackson Pollock was a patient of the Jungian psychologist Joseph Henderson: a treatment that coincided with the artist’s growing interest in Surrealism, and a concurrence of events that resulted in a creative outpouring. Between 1938 and 1943, Pollock produced numerous pictographic drawings based on striking symbolic motifs, including a cache of 83 drawings provided to Henderson as material for analytical aids.

Works in the collection show a close association with such ‘psychoanalytic drawings’, both in style and subject matter. In Untitled c#1939–42 the viewer is presented with the rump of a horse, shown in multiple views over several moments in time. The face of a bull appears at the lower left, looking directly at the viewer with a single yellow eye. Its enormous mass appears conjoined with the horse into a condensed, almost vortex-like accumulation of small, short pencil strokes. In the lower left corner, the horse figure dissipates into an array of empty eye sockets and skulls, finally coming to rest on the ground as a single white bone. This drawing, in particular, seems to evoke a life-and-death cycle, something that Pollock often symbolically explored in both his paintings and his drawings.

Jaklyn Babington

Jackson Pollock

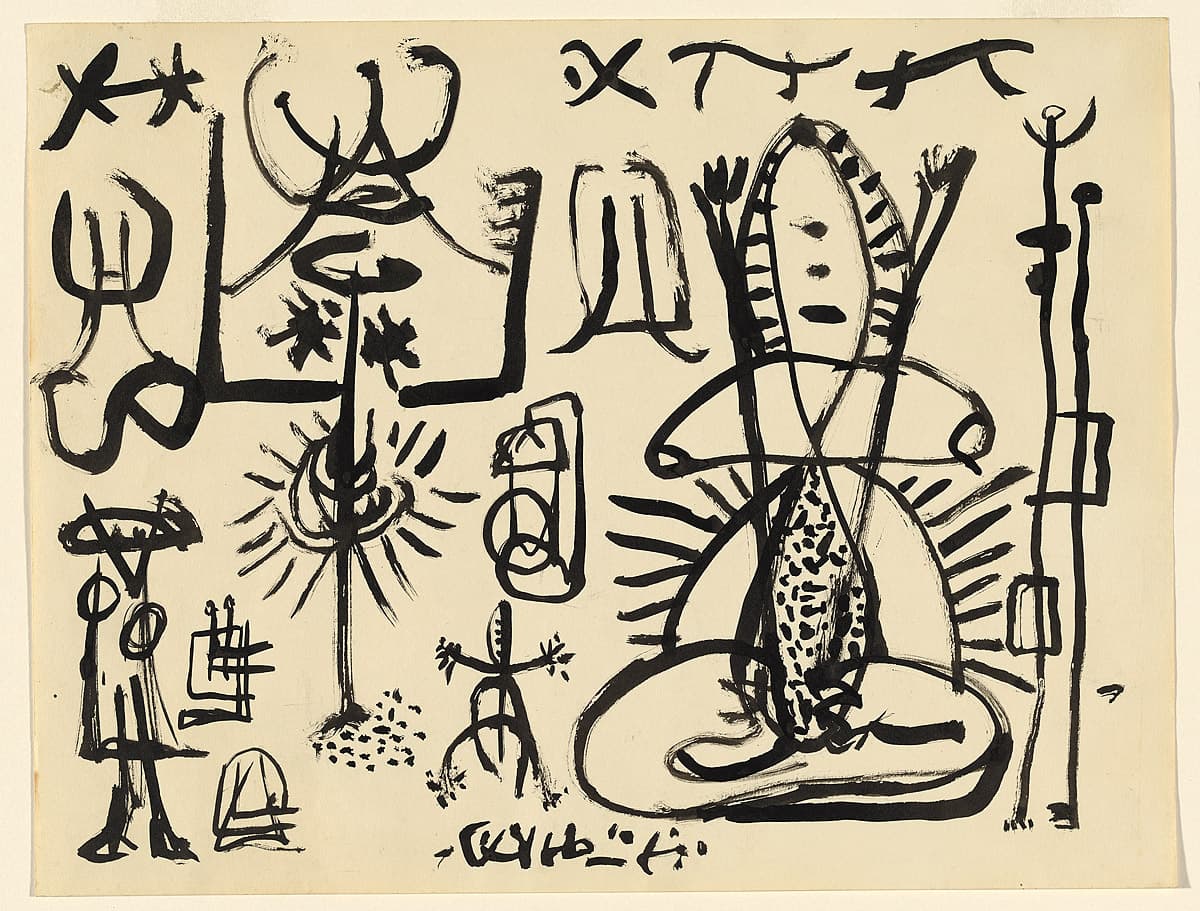

Learn moreUntitled 1939-42

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1986

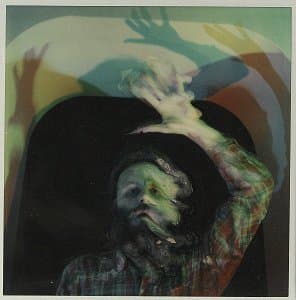

More detail | PermalinkJackson Pollock was a patient of the Jungian psychologist Joseph Henderson: a treatment that coincided with the artist’s growing interest in Surrealism, and a concurrence of events that resulted in a creative outpouring. Between 1938 and 1943, Pollock produced numerous pictographic drawings based on striking symbolic motifs, including a cache of 83 drawings provided to Henderson as material for analytical aids.

Jaklyn Babington

Jackson Pollock

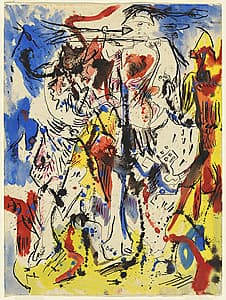

Learn moreUntitled c.1943

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1986

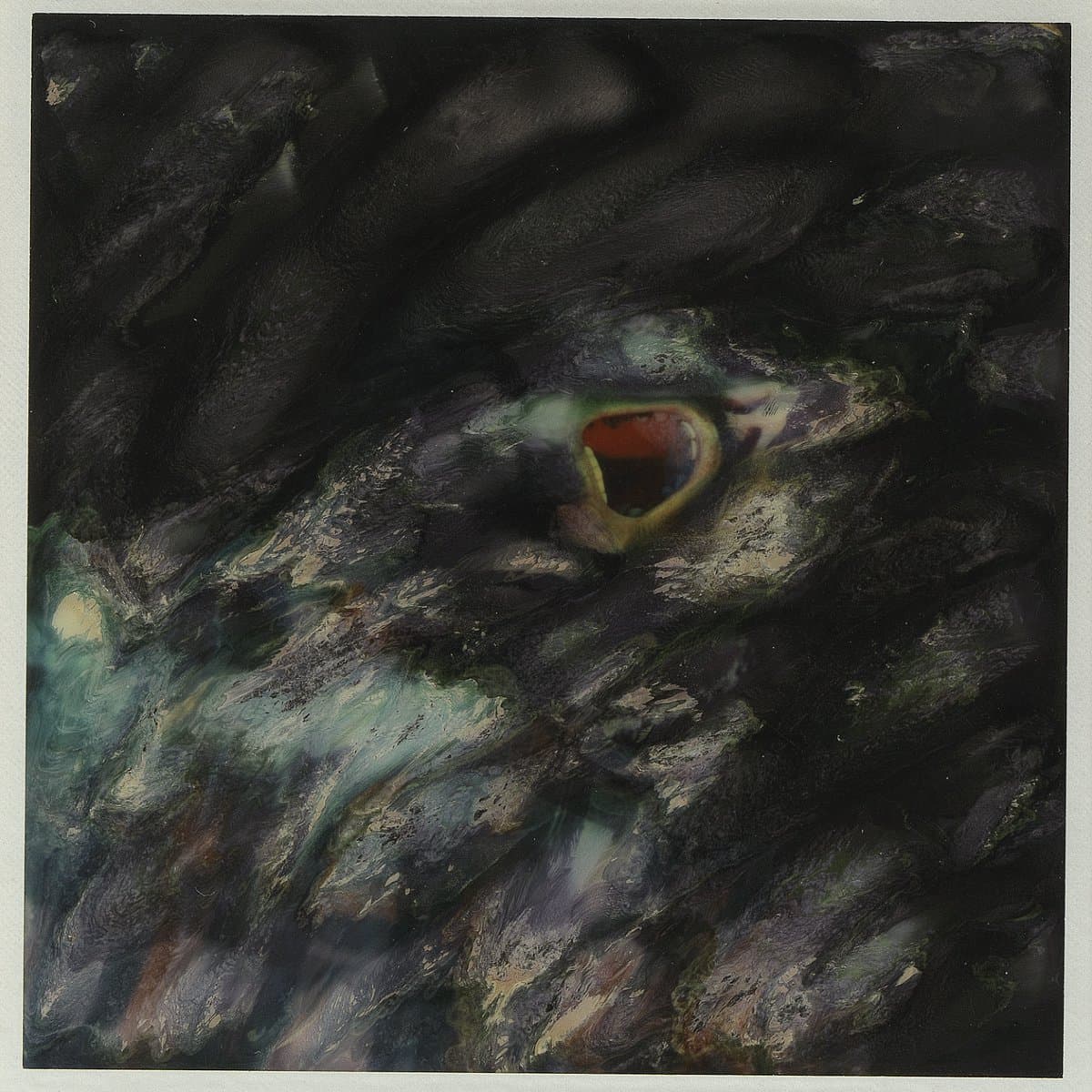

More detail | PermalinkJackson Pollock was a patient of the Jungian psychologist Joseph Henderson: a treatment that coincided with the artist’s growing interest in Surrealism, and a concurrence of events that resulted in a creative outpouring. Between 1938 and 1943, Pollock produced numerous pictographic drawings based on striking symbolic motifs, including a cache of 83 drawings provided to Henderson as material for analytical aids.

The artist’s striking division of the composition Untitled c#1943 into two distinct levels can be interpreted along Jungian lines. The top section—rendered in carefully shaded detail—may represent the ‘personal unconscious’, while the lower section—a loosely formed composition of lines and biomorphic shapes—may be seen to represent the deeper level of Jungian unconscious, the ‘collective unconscious’. It was this deeper level of the psyche from which Pollock and many of the Surrealists wished to draw their expressive imagery. As a collection of lightly executed curvilinear lines and separated organic shapes, the lower half of this work appears to have been created using an automatist technique.

Jaklyn Babington

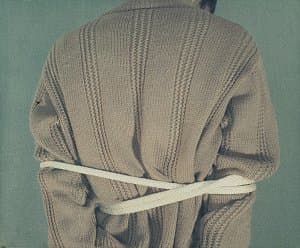

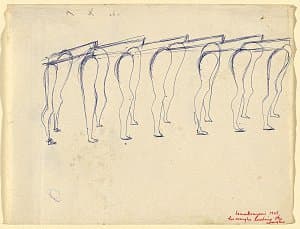

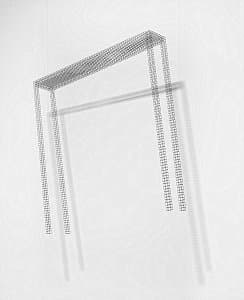

Louise Bourgeois

Learn moreC.O.Y.O.T.E. 1941-48

© The Easton Foundation. VAGA/Copyright Agency Purchased 1981

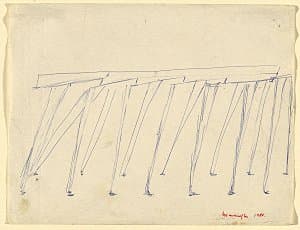

More detail | PermalinkOne of Louise Bourgeois’ earliest major sculptures, C.O.Y.O.T.E. 1941–48, and two related pieces, both titled The blind leading the blind,[i] were begun in 1941 when increased studio space gave her the opportunity to work on a large scale for the first time. This was a turning point in her career, the artist reflected in 1979, ‘because we moved to the so‑called Stuyvesant Folly, which had an immense roof where nobody ever went and I spent my time there. It was very large and I could leave my pieces without being bothered. At this point the size and number of pieces changed.’[ii] Lucy Lippard has pointed out that the combination of human and architectural elements in these sculptures—legs and lintel—can be found in Bourgeois’ earlier works: drawings, paintings and small carved and painted wooden sculptures in which tall, narrow buildings sprout stilts or legs.[iii] When she first arrived in New York from Paris in 1938, Bourgeois recalled being ‘struck by the brownstones, which were a form of habitat I had never seen, and since they were very large and very high and very narrow they reminded me of the human body’.[iv]

Bourgeois herself traced the genesis of C.O.Y.O.T.E. and The blind leading the blind to childhood memories, when she and her brother crouched beneath the kitchen table watching the legs of their parents move back and forth as they prepared a meal.[v] Referring specifically to this work, she said:

It represents an army of legs, two by two, that holds together. Eight pairs of legs. The reason this blind army of legs does not fall, even though the legs are always afraid of falling, since they come to a point, is that they hold on to each other. This is exactly what I felt when I was a child, when I was hiding under the table. My brother was following me like a shadow; I was blind with fear and so was he … [and I concluded that my parents] were not friendly. I decided that the outside was not friendly. And I was afraid, simply afraid. I couldn’t understand their purpose, which was to prepare lunch. I didn’t understand why they were walking around the table. Why would one pair of legs interfere with the other visually, physically? There were their legs and the table’s legs. It really just made me wonder where I fitted in.[vi]

If the form of these sculptures owed something to childhood memories, their title The blind leading the blind—a title that was also originally applied to C.O.Y.O.T.E.—had a very contemporary relevance for Bourgeois. Taken from the New Testament (Matthew 15:14: ‘if the blind lead the blind, both shall fall into the ditch’), the title was chosen for works in which the artist saw ‘catastrophe’, ‘a chain of pain’, ‘people fated to be destroyed together’.[vii] The sculptures were made at the height of the Cold War, at a time when her friends, the artists Marcel Duchamp, Amédée Ozenfant and André Lhote, were under investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee, suspected of being Communists.

In 1979, in preparation for her exhibition at the Xavier Fourcade Gallery in September, Bourgeois gave a new title to one of The blind leading the blind sculptures, and repainted it, covering the original black and red colour scheme with flesh‑pink paint. The new title, C.O.Y.O.T.E., stands for ‘Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics’ and was taken from a tract written by Bourgeois’ friend Margot Saint James, in which she argued the right of prostitutes to a reasonable workers’ organisation, that is, the right to belong to a union. Bourgeois explained:

The blind leading the blind is a piece that brings me to the feminist cause. Another, which is very close, is C.O.YO.T.E., which was the name of the prostitutes’ group. All they can do is hold on to each other. Individually they couldn’t even stand on their feet, but holding on to each other, they make it. It’s also a comment on failures, on shortcomings, on being disabled. They huddle together, and through their positive attitude toward each other they summon the energy necessary to stand against the world. They conquer fear enough to finally express themselves and be what they are.[viii]

C.O.YO.T.E., in declaring Bourgeois’ allegiance to the collective, suggests both the right to self-determination and a rallying cry for the oppressed everywhere.

Christine Dixon[ix]

[i] The blind leading the blind 1949, Detroit Institute of Arts, at https://www.dia.org/art/collection/object/blind-leading-blind-35229, accessed 16 February 2018, and The blind leading the blind 1941–48, collection of the artist, New York.

[ii] Bourgeois, quoted in Marsha Pels, ‘Louise Bourgeois: A Search for Gravity’, Art International, vol 23, no 7, October 1979, p 51.

[iii] Lucy R Lippard, ‘The blind leading the blind’, Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, vol 59, no 1, Spring 1981, p 27.

[iv] Corinne Robins, ‘Louise Bourgeois: Primordial Environments’, Arts Magazine, vol 50, no 10, June 1976, pp 81–3.

[v] Kay Larson, ‘Louise Bourgeois: Body language spoken here’, Village Voice, 24–30 September 1980, p 83.

[vi] Donald Kuspit, Bourgeois: an interview with Louise Bourgeois, Vintage Books, New York, 1988, pp 26–7.

[vii] Lippard, p 27.

[viii] Kuspit, pp 70–2.

[ix] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 209–11.

Jackson Pollock

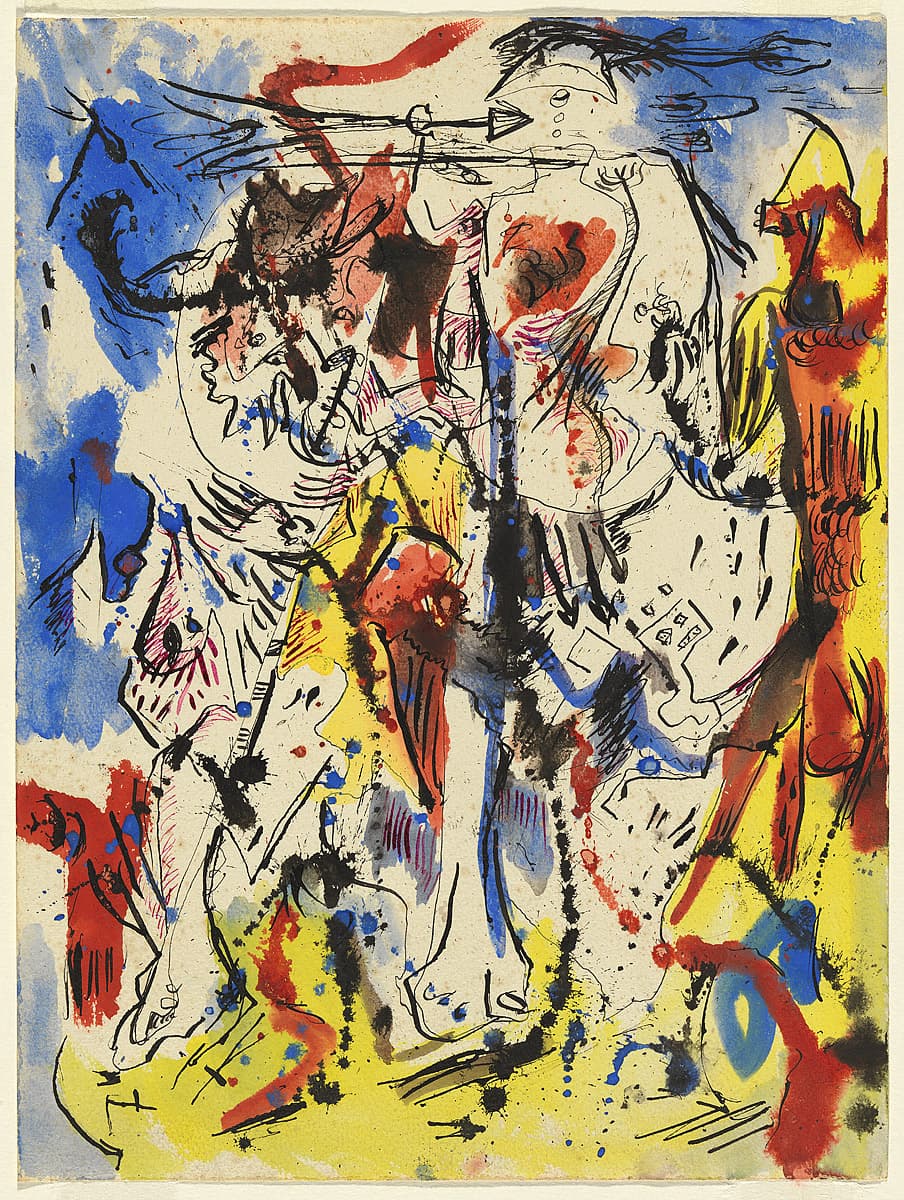

Learn moreUntitled c.1944

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1985

More detail | PermalinkJackson Pollock was a patient of the Jungian psychologist Joseph Henderson: a treatment that coincided with the artist’s growing interest in Surrealism, and a concurrence of events that resulted in a creative outpouring. Between 1938 and 1943, Pollock produced numerous pictographic drawings based on striking symbolic motifs, including a cache of 83 drawings provided to Henderson as material for analytical aids.

Rendered in a restless, black ink line, a horse and its rider emerges as the central image of the drawing Untitled c#1944. The rider wears a helmet adorned with feathers, or perhaps tassels, while the horse strides from right to left across the picture plane, with stark white forelegs and solid hoofs. The abstract background is a tangle of undefined areas of blue and yellow applied in loosely brushed formations, spiky black ink splashes and erratic red highlights. It is difficult to distinguish the horse and its rider from its heavily worked backdrop—the figurative subject matter is almost completely absorbed by the energetic activity of the background.

From a retrospective viewpoint, we can read Pollock’s use of spatter and drip-like application of ink as an allusion to what was to come in his future work. In this way, Untitled c#1944 displays Pollock’s transition toward a mature style, a style that was to be celebrated for its ‘over-all’ compositional structure and for the triumph of the abstract over the figurative.

Jaklyn Babington

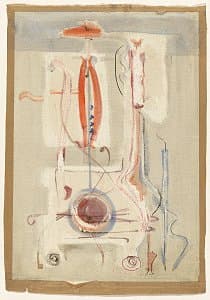

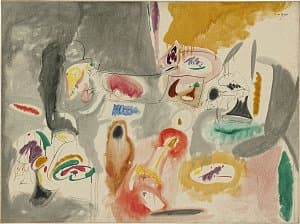

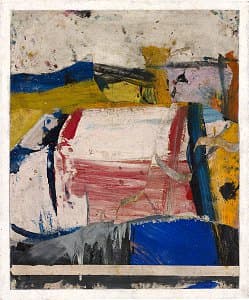

Hans Hofmann

Learn moreUntitled 1943

© Renate, Hans & Maria Hofmann Trust. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1980

More detail | PermalinkThe brilliant colouring and freely expressive forms of Untitled 1943 disguise the sophistication and development of Hans Hofmann’s style after moving to the United States in 1932. Even more than other emigrés, Hofmann brought with him a vast knowledge of avant-garde styles and practices, evident in his history and friendships in Germany and France in the first decades of the twentieth century. Hofmann studied art in Munich and Paris, where he was acquainted with artists such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Hofmann left Paris just before the outbreak of war in 1914, and stayed in Munich for the duration. There he was a friend of Wassily Kandinsky’s partner Gabriele Münter. After Kandinsky was expelled as an enemy alien and returned to Moscow, Münter asked Hofmann to look after his paintings until they could be retrieved after the war.

Such exposure to the most important abstract artist of the time, especially his lyrical Compositions and Improvisations, has a legacy in Hofmann’s work that can be seen in Untitled. Sheer energy is released by a large field of yellow watercolour overlaid by dynamic lines of brush and ink. Curved yellow and green shapes swoop from the upper right, and break into an opposing broken path that reaches down into the lower right. The intensity of colour is partially offset by the semi-transparent medium of watercolour, and Hofmann’s artful placement of almost pure blocks of paint side-by-side. Rectangles of orange and red are counterpointed by violet and blue triangles and circles, becoming a whole that forms a powerful, joyously agitated landscape.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[i]

[i] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures in the Australian National Gallery 1870–1970, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 306–7, by Christine Dixon.

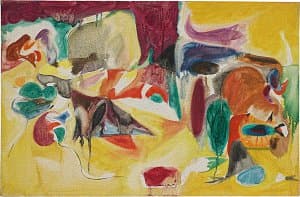

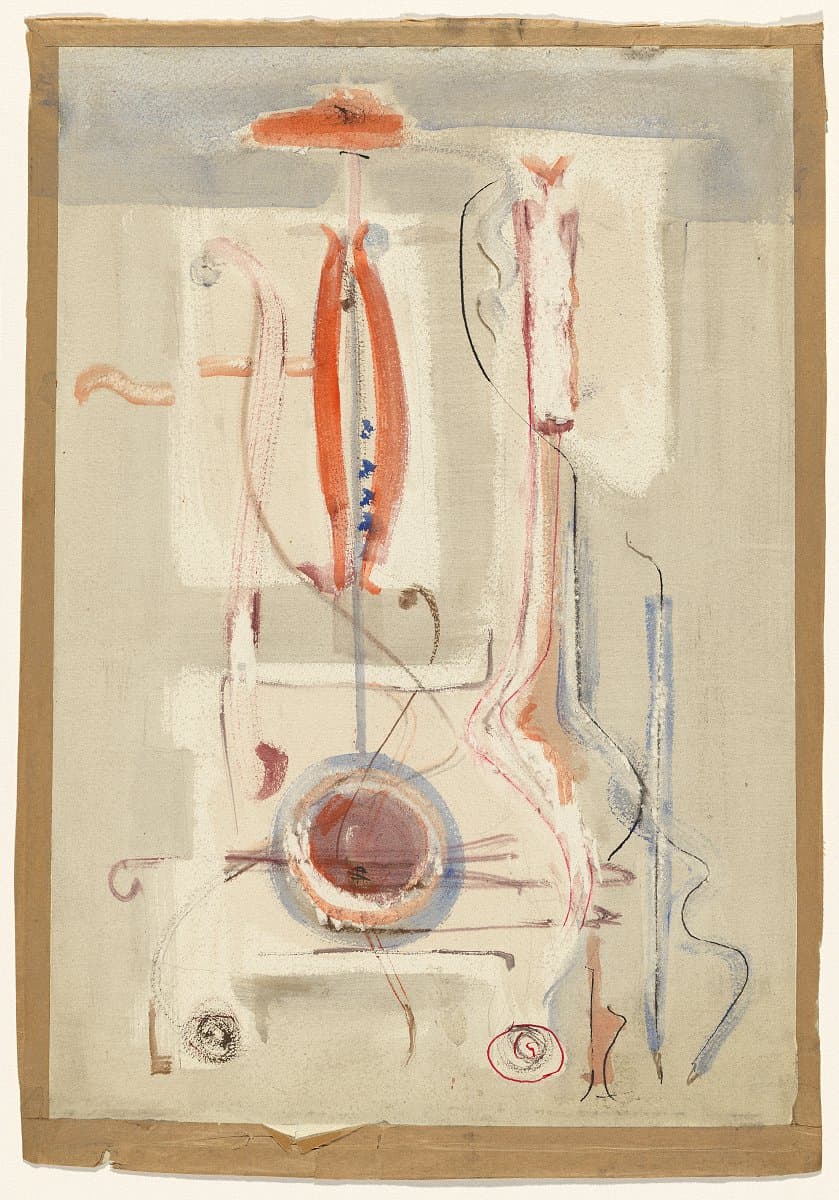

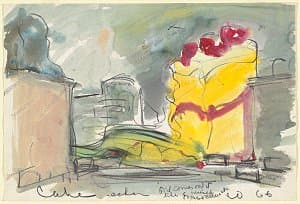

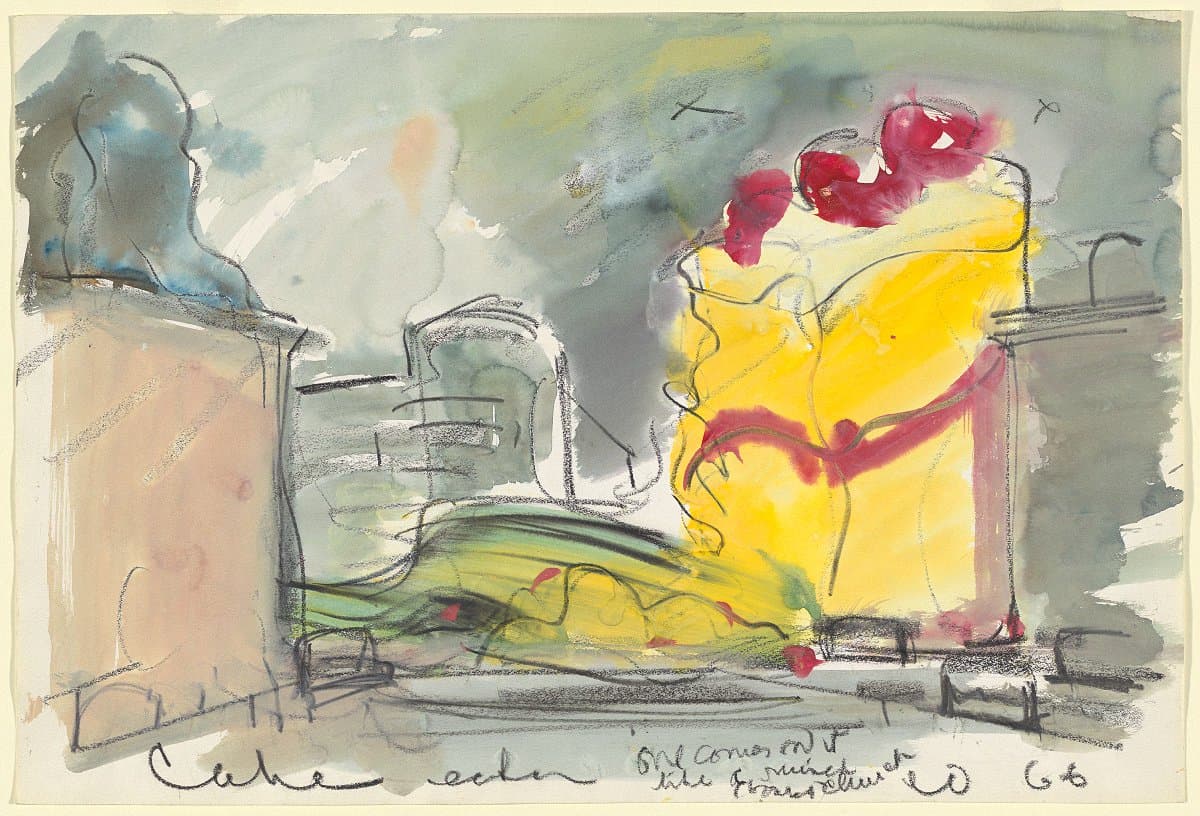

Arshile Gorky

Learn moreUntitled 1944

© Arshile Gorky. ADAGP/Copyright Agency Purchased 1972

More detail | PermalinkUnder the threat of persecution, Arshile Gorky fled Turkish Armenia with other members of his family and arrived in the United States in 1920. After studying at the New School of Design in Boston, he moved to New York and later met John Graham, David Burliuk, Willem de Kooning and Stuart Davis. In 1930 he participated in a group exhibition of young artists at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Gorky moved with his wife and children to the home of his parents-in-law at Crooked Run Farm in Hamilton, Virginia in the spring of 1944, where he worked for nine months, producing a large body of drawings that inspired the paintings he made later, in the winter. It is likely that Untitled was painted in November or December of that year, and was based on one of these drawings.

As can also be traced in Mark Rothko’s Untitled watercolour of 1944–46 (see p xx), the influence of European Surrealist painters was being naturalised by the painters of the New York School, including Gorky. Especially influential were paintings by Joan Miró and the Surrealist compositions of Picasso. Gorky’s Untitled owes much to his admiration for Miró, whose works were known in New York from the inaugural exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1931.

Although he employed similarly biomorphic forms, Gorky’s technique is more textural than Miró’s, and much denser in its composition. Untitled, like many of Gorky’s so-called abstract works, remains firmly based on landscape elements—the hills, rocks and trees that make up his observed world—carefully abstracted into their final form. Strong and vigorously worked elements unite with swathes of luminous transparent colour in an interplay of light and dark, warm and cool, and sharp and rounded forms. Despite recurring ambiguities about what are figures and what is ground, the painting strongly hints at a landscape of organic objects in three-dimensional space.

Untitled shows traces of a pencil grid, which indicates that the composition was directly transferred from a drawing. This process was common for Gorky, although it contradicts much of the rhetoric surrounding Surrealism’s automatism. The artist carefully worked out his compositions in advance through drawings, and reused them with different colour schemes and textures; it is clear that the spontaneous influence of the subconscious mind had a limited role in Gorky’s work.

Much knowledge of his technique disappeared after a disastrous fire in 1946 destroyed his studio, thousands of drawings and most of his paintings. Untitled survived because Gorky had already given the painting to André Breton, the spokesman for the Surrealist movement who fled to New York after the Nazi invasion of France. Gorky first met Breton in the winter of 1944, at much the same time that he was working on Untitled. The painting was probably given on the occasion of Gorky’s first exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery, New York, in March 1945, to which Breton had contributed the catalogue introduction, which was also used as a concluding chapter in the second edition of his book Surrealism and painting.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[1]

[1] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 214–16, by Christine Dixon.

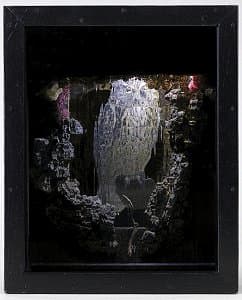

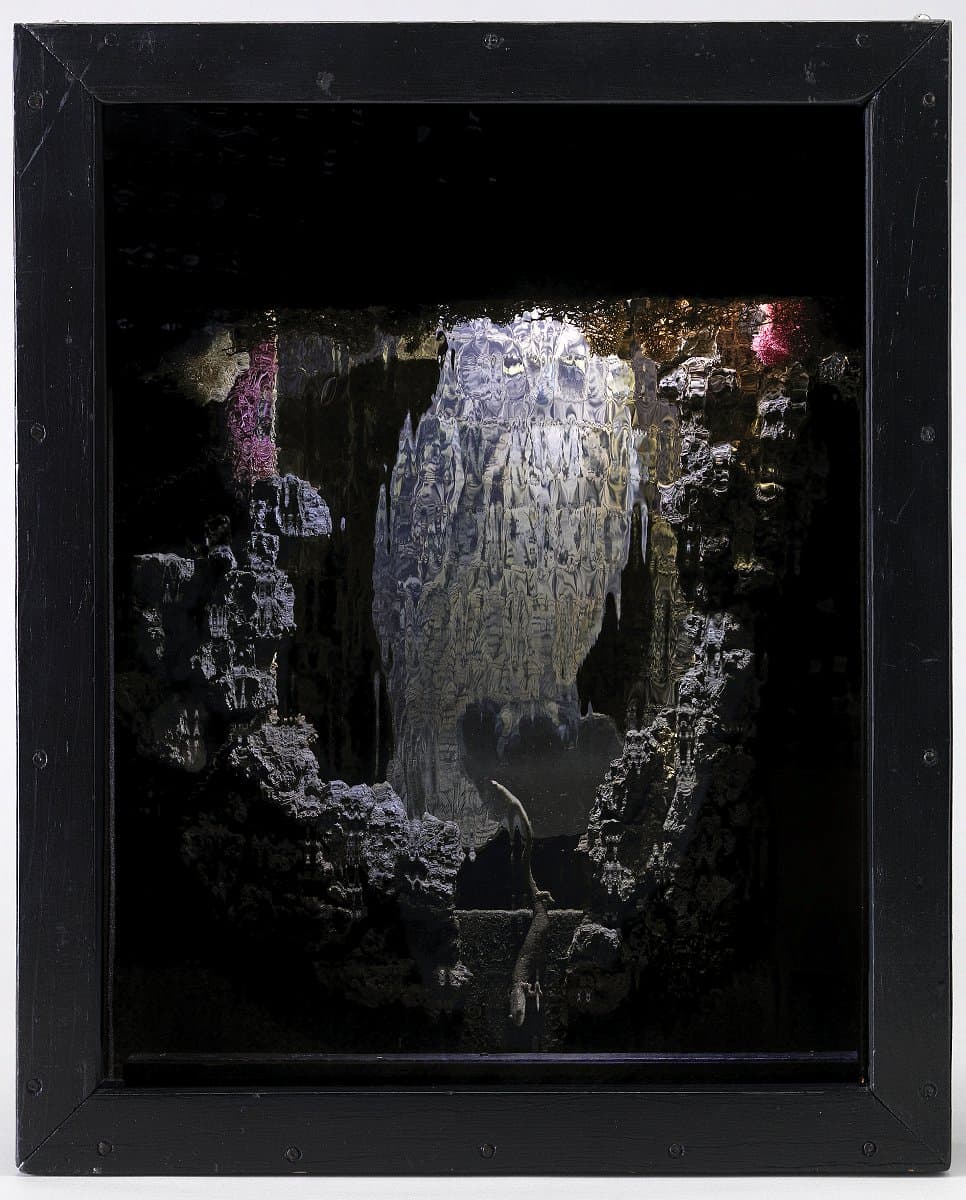

Joseph Cornell

Learn moreUntitled (Owl box) c.1946-48

© Joseph Cornell. VAGA/Copyright Agency Purchased 1980

More detail | PermalinkJoseph Cornell was acquainted with many émigré European artists, including a number of Surrealists who settled in or moved through New York. Their ideas inflect his work and his creations were, in turn, influential in introducing these ideas further afield. An avid collector, Cornell scoured Manhattan’s antique bookshops and second-hand stores for paper ephemera and small objects to make his signature glass-fronted boxes. His first box was shown in the Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1936. From his knowledge of European culture, art and literature the reclusive artist, who never travelled beyond New York, created his own microcosms, self-contained worlds in which to explore life hermetically.

Cornell worked on owl boxes from the early 1940s to the mid 50s, keeping track of them in his diaries.[i] While birds were a common feature of his boxes, his owl constructions, such as Untitled (Owl box) c#1946–48, have a particular character, placed in diorama-type settings that he referred to as ‘woodland habitats’ or ‘deep forest interiors’. In this box, a secret world of undergrowth constructed from pieces of dry wood and lichen surrounds the owl—an illustration glued to a plywood backing. Wood dust adhered with glue covers exposed areas of the inner plywood frame, while several streaks of gold paint are dripped onto the bark and the back wall. At the top of the box is a lamp fitting hidden by the frame. The habitat becomes visible only when this lamp is switched on, taking on a soft blue tint from the rippled blue glass pane, against which the eyes of the owl are yellow and bright. The owl appears as if seated in its bower in shimmering distant moonlight.

Lucina Ward[ii]

[i] Several entries record Cornell’s processes; the entry for 15 April 1946, for example, reads: ‘discovery for the owl box in progress a particularly fine example of rotted tree from which a piece of bark and clinging trailing shrubbery branches had fallen. Took off by the handful the wood from outer part of trunk which was in a powder state-lined box that evening …’ Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Joseph Cornell Papers, diaries, undated and 1930–72 (reel 1059, frame 365). Other owl boxes include Untitled (Owl box) 1945–46, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris and Untitled (Owl) c#1948–50, Joseph Cornell Collection, Chicago.

[ii] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American paintings and sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 224–5.

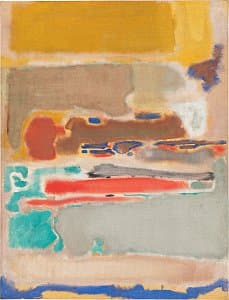

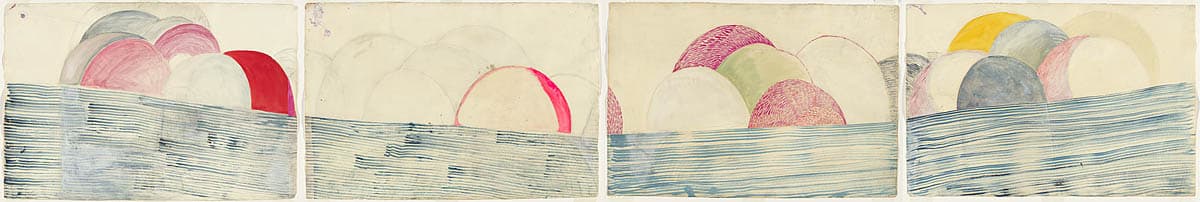

Mark Rothko

Learn moreUntitled 1944-46

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko. ARS/Copyright Agency Gift of American Friends of the National Gallery of Australia, Inc., New York, NY, USA, made possible with the generous support of Mark Rothko Foundation, 1986

More detail | PermalinkUntitled c#1944–46 is a delicate watercolour, pen, ink and pencil drawing that predates Mark Rothko’s paintings in the NGA collection and is dramatically different in style. Like many Abstract Expressionist painters in New York at the time, Rothko developed an interest in Surrealism, mythology and spiritual symbols before which his early style of broadly-painted realism gave way. This drawing displays a thin, sinuous line that curves from the upper left down to the lower right and another that is centred and vertical. Both scroll-like marks cross a section of repeated horizontal lines in the lower half of the drawing. This arrangement can be recognised as musical notation—the symbols of a staff and clef. Furthermore, the large circular shape in the lower quadrant of the drawing appears as the sound hole in the base of a musical instrument, perhaps a mandolin, with its thin neck standing straight and embellished with strings, blue machine heads and an orange wooden scroll.

As a young man, Rothko had taught himself to play both the mandolin and the piano; throughout his career as a painter, music was a constant source of inspiration and connection to the spiritual. Even the manner in which Rothko titled his paintings, by number or colour, had a distinct relation to musical composition. Although the overall style of the drawing is representational, Rothko has taken special care in his selection of colour, contrasting the orange and blue of his forms against lightly washed, abstract fields that serve as a backdrop. The ghostly shadow along the upper section of the composition is a curious element; this geometric form hints at the rectangular slabs Rothko later established as his signature style.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[i]

[i] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery Canberra, 1992, pp 248–9, by Steven Tonkin and Jaklyn Babington.

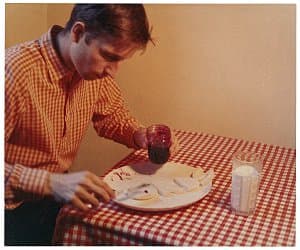

Jackson Pollock

Learn moreTotem lesson 2 1945

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1986

More detail | PermalinkOne of the most influential artists of the Abstract Expressionist movement, Jackson Pollock’s style evolved from his early figurative work of the 1930s to the famous drip paintings of the 1950s. Pollock grew up in the American west and remained deeply interested in the sand painting ceremonies of the Navajo, which is reflected in Totem lesson 2 1945, the second of two paintings with the same title. Totem lesson 1 was completed in October 1944.[1]

The title evokes the contemporary enthusiasm for American Indian art and it has been suggested that the central motif could be a painterly variation of the Sky Father image in a Navajo sand painting illustrated in Indian Art of the United States, the catalogue of an exhibition staged at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1941. Such an image may well have been in the back of Pollock’s mind when he painted Totem lesson 2, however such influences in his work were loose and associational. Pollock said in 1944: ‘Some people find references to American Indian art and calligraphy in parts of my picture. That wasn’t intentional: probably was the result of early memories and enthusiasms.’[2]

Pollock went on to identify his fascination for French art of the twentieth century: ‘I am particularly impressed with their concept of the source of art being the unconscious. This idea interests me more than these specific painters [European émigré artists in America] do, for the two artists I admire most, Picasso and Miró, are still abroad.’[3] Indeed, Totem lesson 2 may register the impact of Surrealism.

In the final analysis, however, such comparisons accentuate the distinctiveness of Pollock’s mode of painting in Totem lesson 2. At first it comprised a large central image painted in oil, occupying most of the picture space. Before the paint was dry Pollock began editing the composition using ordinary grey house paint, paring away the central figure to a hovering spectre surrounded by swirling splinters of the original design. The normal ground‑figure relationship is reversed—the image is literally disclosed in the process of painting. Finally, returning to oil paint, Pollock animated the composition with abstract, expressive notations such as the wriggling yellow line applied directly with the tube in the upper right.

In his review of Pollock’s second solo exhibition at Art of This Century Gallery in 1945—which included both Totem lesson paintings—art critic Clement Greenberg made extraordinary claims for the 32‑year‑old artist:

Jackson Pollock’s second one‑man show at Art of This Century … establishes him, in my opinion, as the strongest painter of his generation and perhaps the greatest one to appear since Miró … Those who find his oils overpowering are advised to approach him through his gouaches, which in trying less to wring every possible ounce of intensity from every square inch of surface achieve greater clarity and are less suffocatingly packed than the oils. Among the latter however, are two—both called Totem lessons—for which I cannot find strong enough words of praise.[4]

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[5]

[1] Francis Valentine O’Connor and Eugene Victor Thaw, Jackson Pollock: A catalogue raisonné of paintings, drawings and other works, 4 vols, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1978, vol 1, p 114, cat 121. Totem lesson 1 is signed and dated lower left, ‘10‑44 Jackson Pollock’; held collection Harry W and Mary Margaret Anderson, Atherton, California.

[2] Arts and Architecture (Los Angeles), February 1944, p 14.

[3] As above.

[4] Clement Greenberg, review, Nation, 7 April 1945, p 39.

[5] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 232–5, 243–4 by Anthony White.

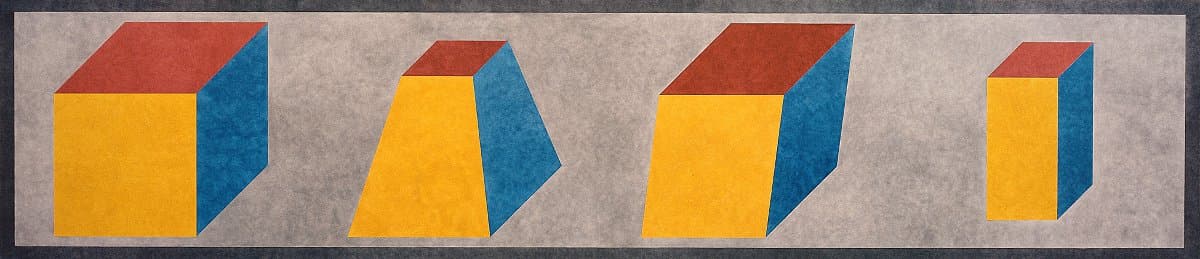

Fritz Glarner

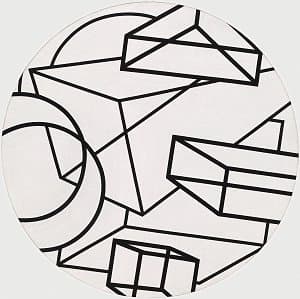

Learn moreRelational painting, tondo no. 4 1946

© 2002 Kunsthaus Zurich. All rights reserved. Purchased 1977

More detail | PermalinkFritz Glarner painted his first tondo in the early 1940s and it became his basic format for over 60 variations painted in the United States. Having studied and worked in both Italy and France, exhibited with the Abstraction-Création group in the 1930s and been influenced by the De Stijl painters and Bauhaus principles, Glarner’s work brings together a range of geometric and spatial principles. His use of the round format for his paintings recalls Renaissance models but here reinvented with an emphatically modern approach. As the artist later explained, the tondo ‘was naturalistic because it could be a sun, a moon, or any symbol because it was concentric and therefore the space around it was undetermined’.[1]

In New York Glarner was closely associated with Piet Mondrian and, while he acknowledged the older artist’s influence, he also made key adjustments. Both artists rely on primary colours but Glarner makes greater use of greys and diagonal forms. As Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond point out, Glarner replaced the ‘balancing of horizontality and verticality achieved in Mondrian’s painting with interlocking rectangles and wedges that expand outwards towards the edges of the canvas’.[2] In Tondo no. 1 and Tondo no. 2 (both 1945) Glarner combines:

abstract realities and the laws of mathematics and geometry within the canvas: the organization of the image, the relationships between the areas, the intensity of the base colours and grey tones are coordinated [to create] a unity that is independent of the world yet internally functional.[3]

In Tondo no. 3 1945 Glarner sought to overcome this figurative ambiguity by dividing the interior of the tondo into a series of angles, successively reiterated towards the edge of the canvas and, by implication, shaping the space beyond the circumference.[4] These ideas were refined in Relational painting, tondo no. 4, painted the following year. While its colours and overall geometry of make it appear flat, the lattice-like sections imply a layering which, again, suggests recession. Moreover, the use of board—instead of the more traditional canvas—gives the work an object-like form.

Towards the end of 1946, the artist settled on the term ‘relational painting’ as an English equivalent for peinture relative, and subsequently applied the term to earlier paintings, as well as his new work. This term suited, as Lloyd and Desmond observe, ‘the kind of abstract painting he pursued, focused on relating geometric shapes and ground through colour, in ways which would make shape and ground alternate to produce what he called “pumping planes”’.[5] ‘In painting’, Glarner said, ‘form has to lose its specific identity and space has to acquire one by determination.’[6]

Lucina Ward

[1] Dore Ashton, ‘Fritz Glarner’, Art International, vol 7, no 1, January 1963, pp 48–55.

[2] Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, p 246.

[3] Tondo no. 1 1945, Kunsthaus, Zurich, at https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/asset/relational-painting-tondo-no-1/CAEKErPhRQvmjQ, accessed 16 February 2018. Tondo no. 2 1945, whereabouts unknown.

[4] Tondo no. 3 1945, Collection Lucie Glarner, Locarno.

[5] Lloyd and Desmond, p 246.

[6] ‘What abstract art means to me’, Glarner’s response to a symposium held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 5 February 1951, reprinted in the Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, vol 18, no 3, Spring 1951, pp 10–11, see also http://www.jstor.org/stable/4058250, accessed 16 February 2018.

Arshile Gorky

Learn morePlumage landscape 1947

© Arshile Gorky. ADAGP/Copyright Agency Purchased 1973

More detail | PermalinkArshille Gorky’s paintings were invariably preceded by a preliminary drawing. He would select from existing drawings, usually done in the warmer months, to use as the basis for a painting or a number of paintings. The drawing, once transferred to the canvas, served as an armature for his colour. This schema would be interpreted freely and could be worked up in a number of versions, each being a variation on a theme. Two other works completed in 1947 share the same underlying drawing as Plumage landscape: Year after year and Theme for Plumage landscape (call for Virginia).[1]

In Plumage landscape, colour is varied around the common linear structure, thereby allowing individual emphasis and interpretation. The oil paint has been thinned to the consistency of watercolour to produce washes of pure and transparent colour, which preserve the firm black lines of the drawing and maximise the soft organic fluidity of each colour accent. Viridian elements scattered across the picture plane unite the composition. The daring use of tertiary and pastel hues—pinks, ochres, greys—allows the viewer to concentrate on form as well as colour, and emphasises the painting’s high tonality.

Gorky’s titles are usually poetic and evocative rather than descriptive. ‘Plumage landscape’ is a typical creation, conflating the iridescence of birds’ feathers with the idea of moving through a landscape. Ethel Schwabacher, a student of Gorky’s in the mid 1940s, referred to the accents of colour as ‘plumes’ when writing about his work in 1951, and William C Seitz, in a publication of 1962, claimed the term was Gorky’s own.[2] If this is the case, then it may offer some insight into the title of the painting as, literally, a landscape made with aureoles of paint.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[3]

[1] Respectively, Ex-collection Mr and Mrs Gifford Phillips, New York; and Private collection.

[2] See Ethel Schwabacher’s introduction to Arshile Gorky memorial exhibition, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1951; William C Seitz first claimed that plumes ‘is what Gorky called them’ in the catalogue Arshile Gorky: Paintings, drawings, studies, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Washington DC, 1962. This claim reappeared in the text that was reprinted for the catalogue for the exhibition at the Tate Gallery, London, Arshile Gorky: Paintings and drawings, Arts Council, London, 1965. Interestingly, in Seitz’s dissertation of 1955, Abstract Expressionist painting in America, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1983, Seitz attributes the term to Schwabacher.

[3] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery Canberra, 1992, p 216, by Christine Dixon.

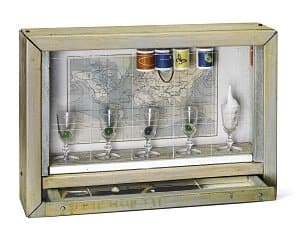

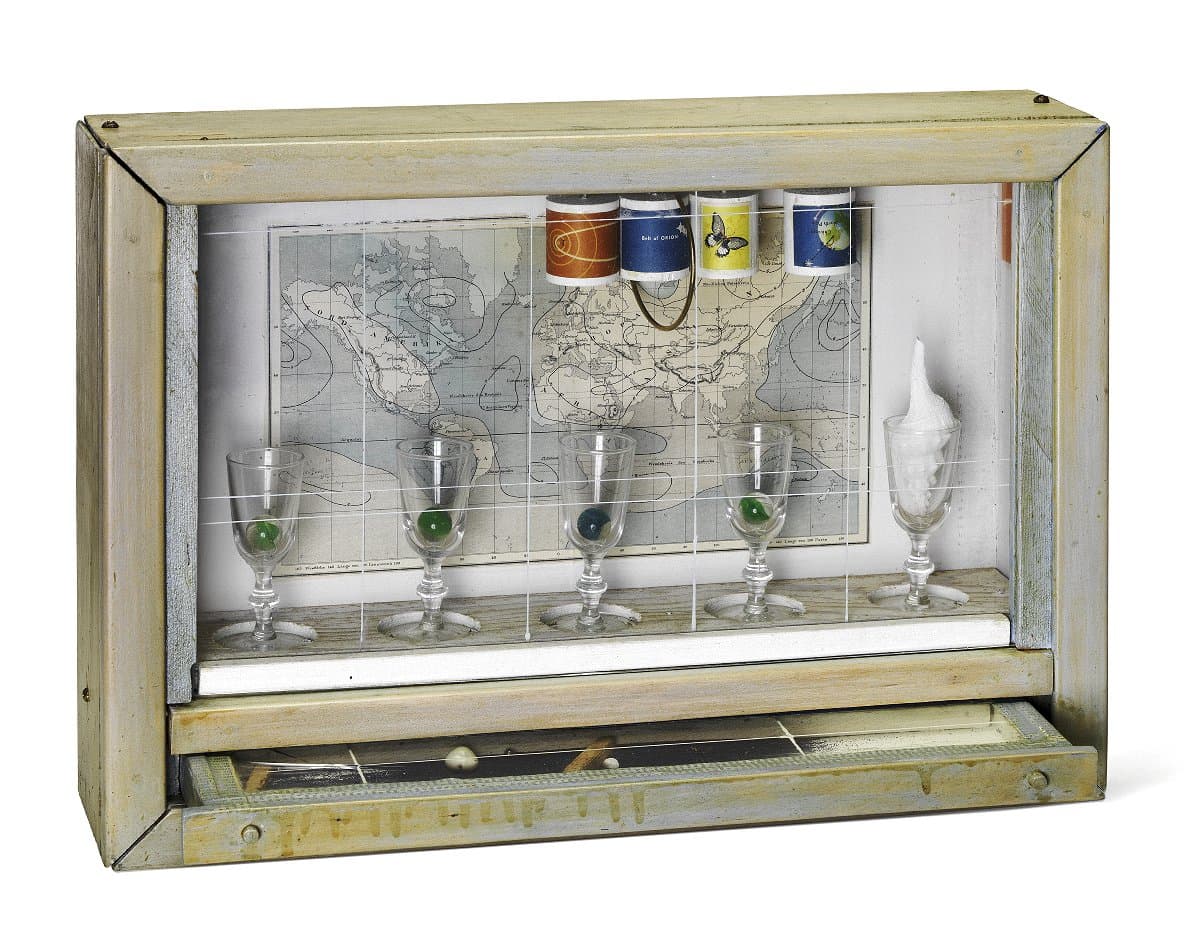

Joseph Cornell

Learn moreUntitled c.1950

© Joseph Cornell. VAGA/Copyright Agency Purchased 1973

More detail | PermalinkJoseph Cornell was acquainted with many émigré European artists, including a number of Surrealists who settled in or moved through New York. Their ideas inflect his work and his creations were, in turn, influential in introducing these ideas further afield. An avid collector, Cornell scoured Manhattan’s antique bookshops and second-hand stores for paper ephemera and small objects to make his signature glass-fronted boxes. His first box was shown in the Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1936. From his knowledge of European culture, art and literature the reclusive artist, who never travelled beyond New York, created his own microcosms, self-contained worlds in which to explore life hermetically.

Cornell admired the detail and finish of seventeenth-century Dutch still-life painting, referring to the genre as ‘ultra-graphic microscopic magic’.[1] The same precision and complexity applies to Untitled c#1950 from the Navigation series. The phrase ‘nostalgia of the sea’ occurs frequently in Cornell’s diaries, and was an emotion he hoped to crystallise in his work.[2] Washed with thin blue paint, as if scoured by seawater, the exterior paintwork of this box has a weathered look. An intriguing map occupies the back of the box, areas of which are washed with a light blue watercolour. On the underside of the box’s roof is a section of a German map showing an expanse of the Atlantic Ocean from the Caribbean to the United Kingdom. Cuttings from a guide to astronomy are attached to four suspended wooden cylindrical blocks. Five liqueur glasses stand in hollows cut into the wood at the bottom of the box—four contain a marble, the fifth holds a white spiral shell. The shallow white drawer is covered with a glass pane and contains a sprinkled mass of dark blue powder, metal ball-bearings, shells and strips of cork. Cornell has drawn a thin grid of white paint on the glass covering the drawer, inspired perhaps by the lines of latitude and longitude on the maps.

Lucina Ward[3]

[1] Undated diary entry, Joseph Cornell Papers (reel 1062, frame 878).

[2] See, for example: ‘nostalgia of the sea / we pick up a piece of wood on the seashore / there is infinite legend & romance about flotsam and jetsam—equivalent in mounting to retain this quality / immaculate aspect of something surviving a hundred years’. Joseph Cornell Papers, source material files I (reel 1067, frame 427).

[3] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American paintings and sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 224–5.

Mark Rothko

Learn moreMultiform 1948

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1981

More detail | PermalinkBy 1947 Rothko’s paintings had become completely abstract, his compositions made up of irregular areas of colour. Untitled (Multiform) 1948 is one of a small group of untitled works, collectively known as Multiforms,[i] painted immediately preceding the mature works for which Rothko is best known. In these transitional paintings Rothko abandoned the surrealist-inspired personal myths and classical themes evident in works such as Untitled c#1944–46, moving towards a fully abstract vocabulary. Writing in 1947, he described his paintings as ‘dramas’, but added that the use by postwar artists of figurative subject matter to convey emotions and experiences was no longer practicable: ‘with us the disguise must be complete. The familiar identity of things has to be pulverised in order to destroy the finite associations with which our society increasingly enshrouds every aspect of our environment.’[ii] In Untitled (Multiform) irregular areas of colour contract and expand, project and retract, as the eye roves over the surface; the changes in tone between darker and lighter areas are so gradual that depth within the painting remains indeterminate. The three large rectangular blocks of colour are precursors—from 1949 the artist made these the subject of all subsequent paintings.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[iii]

[i] The title Multiform does not seem to have been used before Rothko’s death. It appears for the first time in the catalogue for the Rothko exhibition at the 1970 Venice Biennale. It is thought by the staff of the Marlborough Gallery, who prepared this catalogue, that Rothko used the term Multiform generically when referring to his transitional paintings of 1948–49; Bonnie Clearwater, correspondence with the Australian National Gallery, 12 July 1984.

[ii] Mark Rothko, ‘The Romantics were prompted’, Possibilities, no 1, Winter 1947–48, p 84.

[iii] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery Canberra, 1992, pp 248–9, by Steven Tonkin and Jaklyn Babington.

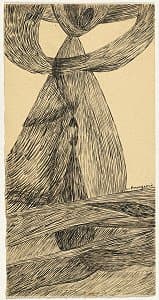

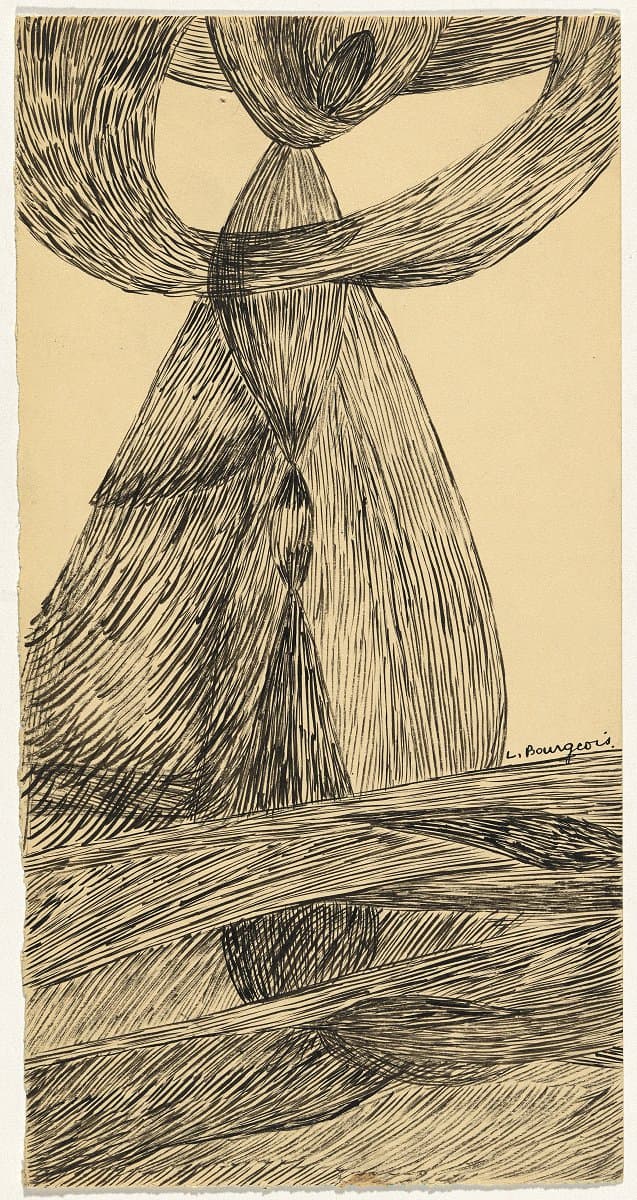

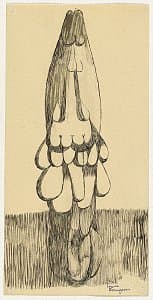

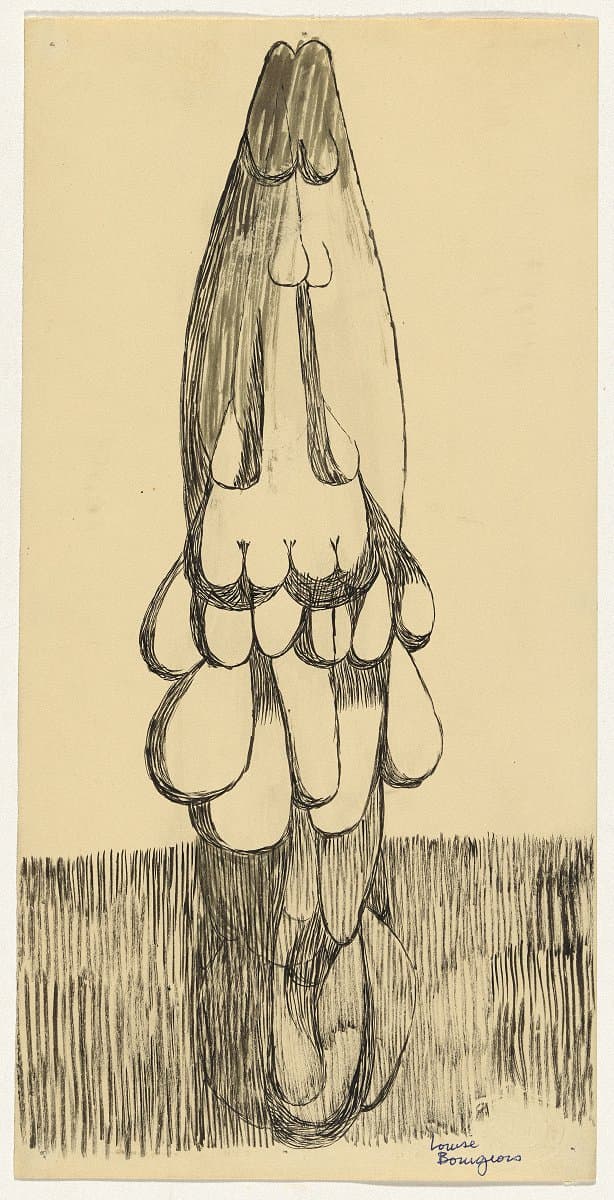

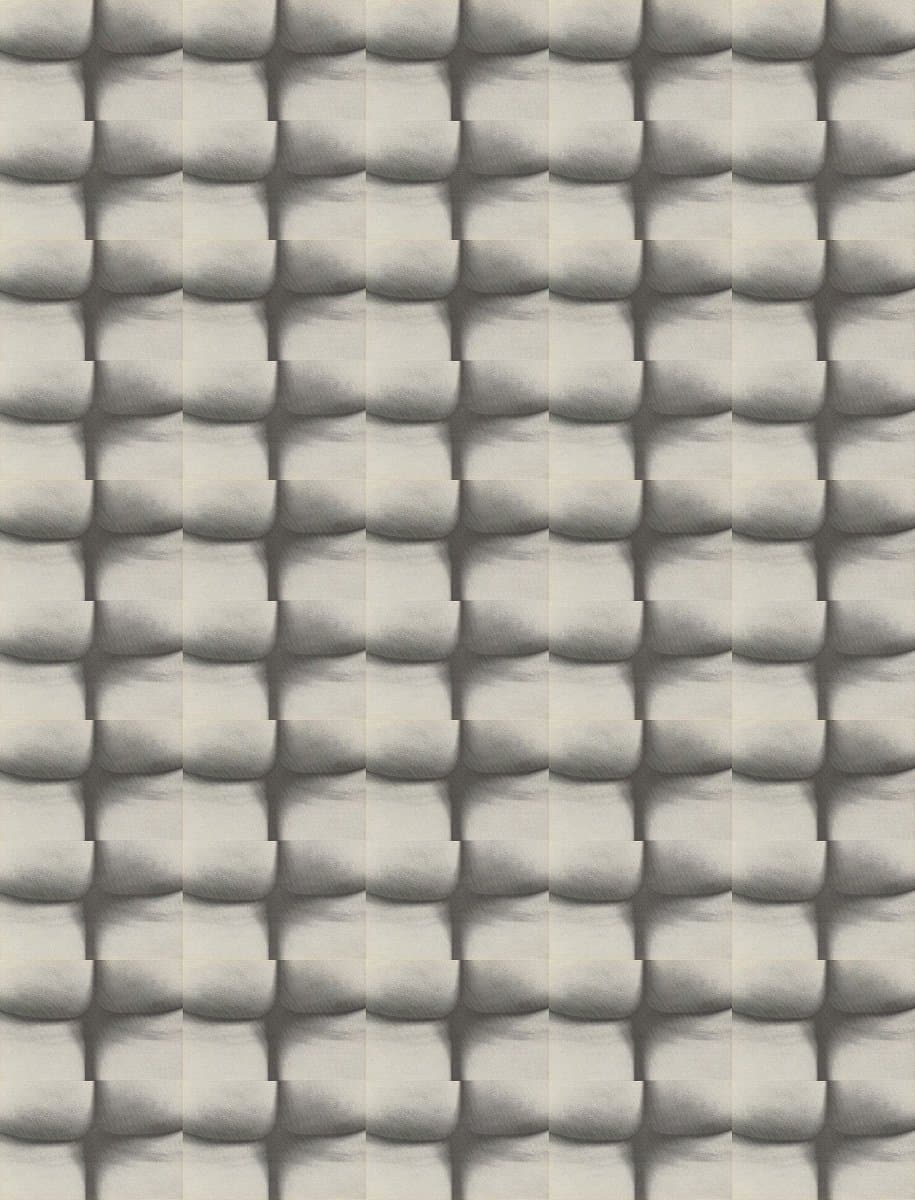

Louise Bourgeois

Learn moreNo title c.1951

© The Easton Foundation. VAGA/Copyright Agency Gift of Linda Quinell 1983

More detail | PermalinkSmall pen and ink drawings dating from the mid 1940s to the early 50s are among the Louise Bourgeois’ most characteristic and important group of works. Depicting fine line drawings widely interpreted as representing strands of long hair or skeins of tapestry yarn—strung loose, knotted and hanging—they are both abstract and autobiographic in nature (Bourgeois wore her hair very long for most of her life). In an exhaustive analysis of the artist’s work, historian Robert Storr suggests that it is with the advent of these drawings that Bourgeois took on her most unique and, arguably, important artistic trait. While always highly articulate in describing her own motivations for making works, these drawings represent the moment when Bourgeois’ art could never again be conclusively interpreted by others as ‘representing any one thing, or class of things’.[i]

Sally Foster

[i] Robert Storr, Intimate geometries: the art and life of Louise Bourgeois, Thames & Hudson, London, 2016, p 112.

Louise Bourgeois

Learn moreNo title c.1951

© The Easton Foundation. VAGA/Copyright Agency Purchased 1983

More detail | PermalinkSmall pen and ink drawings dating from the mid 1940s to the early 50s are among the Louise Bourgeois’ most characteristic and important group of works. Depicting fine line drawings widely interpreted as representing strands of long hair or skeins of tapestry yarn—strung loose, knotted and hanging—they are both abstract and autobiographic in nature (Bourgeois wore her hair very long for most of her life). In an exhaustive analysis of the artist’s work, historian Robert Storr suggests that it is with the advent of these drawings that Bourgeois took on her most unique and, arguably, important artistic trait. While always highly articulate in describing her own motivations for making works, these drawings represent the moment when Bourgeois’ art could never again be conclusively interpreted by others as ‘representing any one thing, or class of things’.[i]

Sally Foster

[i] Robert Storr, Intimate geometries: the art and life of Louise Bourgeois, Thames & Hudson, London, 2016, p 112.

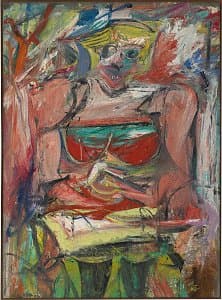

Willem de Kooning

Learn moreWoman V 1952-53

© The Willem de Kooning Foundation, New York. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1974

More detail | PermalinkWillem de Kooning’s first paintings of female figures were made in 1940, some of them inspired by Elaine Fried, who he would later marry.[1] These early works show the contorted poses, folded limbs, clasped hands and, occasionally, exaggerated eyes, mouths and breasts later adopted for his extended series, but are generally more serene, both in paint-handling and in overall mood. Woman V, produced a decade later, personifies the artist’s energy, enthusiasm and, at times, fury for his subject: it seems to encapsulate his comment that flesh is the reason oil paint was invented.[2]

Woman V is the fifth in a series of six paintings depicting three-quarter‑length female figures, either seated or standing, made between 1950 and 1953. The first, Woman I, was begun in June 1950, and repeatedly changed and overpainted by de Kooning, until he abandoned the work in January or February 1952.[3] When art historian Meyer Schapiro saw the painting in the studio, and encouraged the artist to persist, de Kooning’s response was to begin three others: Woman II, Woman III and Woman IV.[4] By the end of June 1952, or perhaps as late as November, with four canvases near completion, de Kooning began Woman V and Woman VI in the autumn and winter of 1952, respectively.[5] The group of six works, exhibited at the Sidney Janis Gallery in March 1953, caused consternation among many artists and critics who felt that de Kooning had betrayed the ideals of abstraction.

Woman V, as John Elderfield observes, takes further the use of bright colour of the earlier works and the dense concentration of paint into rectangular form: it is as if the painting advances and realises the ambitions of the previous women.[6] Because de Kooning anchors the figure to the bottom edge of his composition, all but filling the canvas, the painting’s energy seems compressed. The figure’s square shoulders, her breasts enclosed by her arms, tiny dress and stockinged legs, as well as the agitation of her surroundings, encourage the eye to move around the composition, ‘picking up marginal incident along the way—bodily curves that bend to and from the edges of the canvas; the short, exposed parts of the legs, and the blurry head; and indications of landscape around these features at top and at bottom’.[7]

Various influences for this series have been suggested, both by the artist and several critics, from the Mesopotamian figurines on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, to the grinning mouths of ‘pin-up’ girls, images of which de Kooning often cut from magazines and attached to his work.[8] Because Woman V, like the figures of Woman IV and Woman VI, appears to be standing in water Thomas B Hess has proposed a further influence: Rembrandt’s A woman bathing in a stream 1654.[9] Indeed, while working on the Woman series de Kooning commented that the paintings ‘reminded me very much of my childhood being in Holland, near all that water’.[10] Although the hands of Woman V are now clasped together at the waist, they were once arranged at each side in a gesture resembling that of Rembrandt’s painting, where the wading figure holds up her skirt to clear the water.

Lucina Ward

[1] See, for example, Seated woman c#1940, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and later works such as Queen of hearts 1943–46, Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC.

[2] Marcia Brennan, Modernism’s masculine subjects: Matisse, the New York School, and Post-Painterly Abstraction, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2004, p 72.

[3] The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Rudolph Burckhardt’s and Walter Auerbach’s photographs of Woman I in progress are often reproduced; see, for example, Paul Cummings, Jörn Merkert and Claire Stoullig, Willem de Kooning: Drawings, paintings, sculpture, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 1983, p 176 and John Elderfield et al, De Kooning: A retrospective, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2011, p 248.

[4] Woman II 1952 is also at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Woman III 1952–53, now owned by David Geffen, Los Angeles, was previously part of the collection at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art; Woman IV is at the Nelson Gallery–Atkins Museum, Kansas City. De Kooning further explored the theme in an extensive series of drawings and pastels during the summer of 1952.

[5] Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. For more detail, see also Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 258–9.

[6] Elderfield et al, p 274.

[7] As above.

[8] Sally Yard, ‘Willem de Kooning’s Women’, in Arts Magazine, vol 53, no 3, November 1978, pp 96–101.

[9] National Gallery, London; although de Kooning had not seen Rembrandt’s painting in the flesh, it was widely reproduced, including in an Artnews article in February 1952 about the cleaning of Old Master paintings. Thomas B Hess, ‘Four pictures by de Kooning at Canberra’, Art and Australia, vol 14, nos 3 & 4, January–April 1977, pp 289–96.

[10] Harold Rosenberg, ‘Interview with Willem de Kooning’, Artnews, vol 71, no 5, September 1972, p 57.

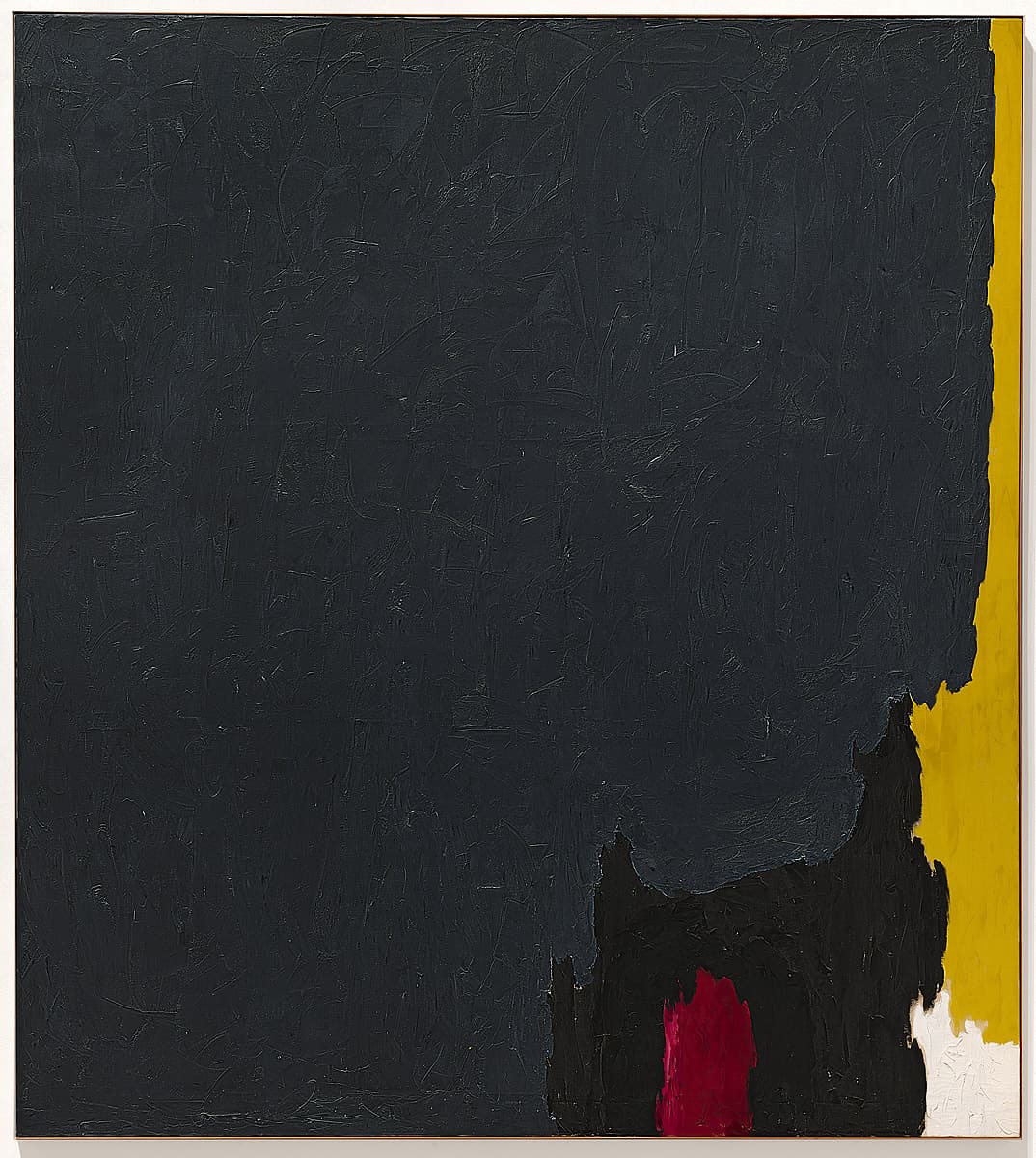

Clyfford Still

Learn more1952-no.2 1952

© The Clyfford Still Estate Purchased 1978

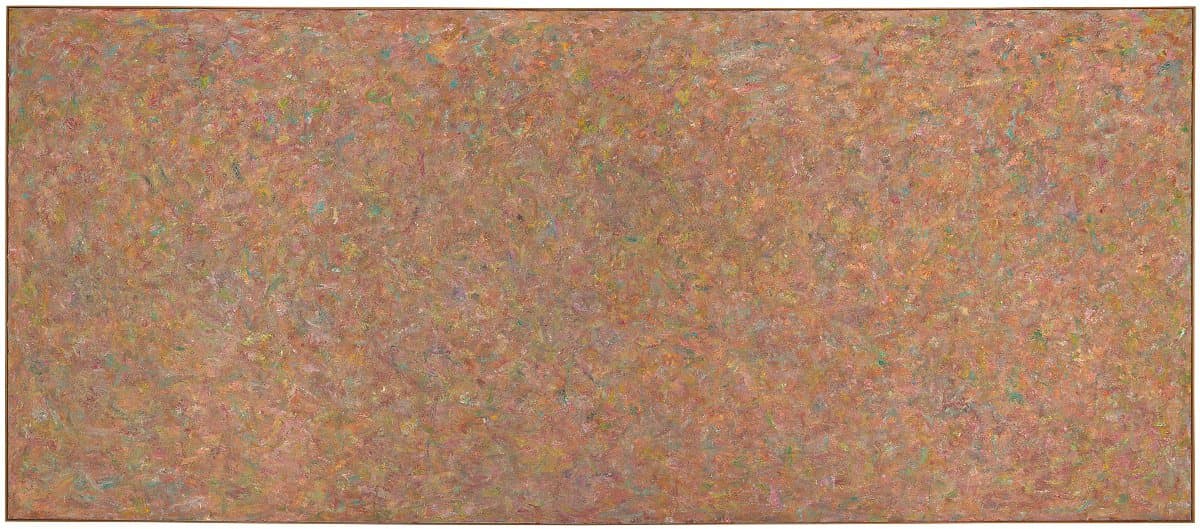

More detail | PermalinkClyfford Still’s association with Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, and other prominent artists he met after moving to New York in 1945, led him to become known as an Abstract Expressionist or ‘action painter’, categories of which Still disapproved. More than other members of the New York School, Still attempted to purge his work of literary allusions and overt graphic symbols, preferring to stress the elements of painting—colour, shape, size—and their formal relationships as his subject matter. He frequently denied any connection between the craggy forms in his paintings and the rugged western landscapes of his childhood: ‘I only paint myself, not nature.’[1] Stripped of conventional associations, he hoped the elements in his paintings could be as pure and abstract as musical notes, and indeed he compared his paintings to orchestral compositions.[2]

Still’s bold creation of overlapping irregular fields of colour asserts paint to be the hero of this work. Most of the canvas is covered with a dense, thickly textured veil of steel grey impasto. A leading edge of bright chrome, yellow and white allows the viewer to perceive a way out of the domineering extent of subdued grey. Another note of contrast is provided by inchoate blotches of black and red.

Despite the artist’s denial of any subject or possible narrative, he portrays a grey curtain that descends on and over the contrasting hues, seeming poised to obscure them. Still’s painting, while minimising three-dimensional and pictorial space, is deeply contemplative, sombre and introspective.

The painting was known variously over the years as Gray picture or Gray painting, however even such a mildly descriptive title would not have suited Still’s austere sensibility. ‘My paintings,’ he wrote, ‘have no titles because I do not wish them to be considered illustrations or pictorial puzzles. If made properly visible they speak for themselves.’[3] Patricia Still, the artist’s widow, has confirmed through her husband’s records that the work is correctly titled 1952–no.2 and was painted in 1952.[4] The painting is further identified by the photographic number PH–773, and is the second version of a work painted in New York in 1951. The first painting, PH–1071, which forms part of the artist's estate, was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 1979.[5] Still often made his own near-replicas of works he regarded as important, before letting them onto the art market, as he distrusted dealers, critics and museums. He wrote in 1972:

Making additional versions is an act I consider necessary when I believe the importance of the idea or breakthrough merits survival on more than one stretch of canvas, especially when it is entrusted to the precarious world of exhibitions or collecting. Although the few replicas I make are usually close to or extensions of the original, each has its special and particular life and is not intended to be just a copy.[6]

Christine Dixon[7]

[1] ‘The fact that I grew up on the prairies has nothing to do with my paintings, what people think they find in them. I paint only myself, not nature,’ from Benjamin Townsend, ‘An interview with Clyfford Still’, in Gallery Notes, Albright-Knox Gallery, vol 24, no 2, Summer 1961, pp 10–16.

[2] Maurice Tuchman, New York School: The first generation, New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, Connecticut, 1965, p 148.

[3] Clyfford Still, quoted from a letter written to the Tate Gallery in 1972, in Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s collection of modern art other than works by British artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke Bernet, London, 1981, p 710.

[4] Mrs Clyfford Still, correspondence with the Australian National Gallery, 11 August 1983.

[5] John P O’Neill (ed), Clyfford Still, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1979, cat 20, p 88.

[6] Letter, 20 July 1972, to Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, quoted in Neal Benezra, ‘Clyfford Still’s Replicas’, in James T Demetrion, Clyfford Still: Paintings 1944–1960, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, New Haven and London, 2001, pp 88–9, 98, n 12.

[7] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 265–7.

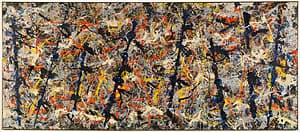

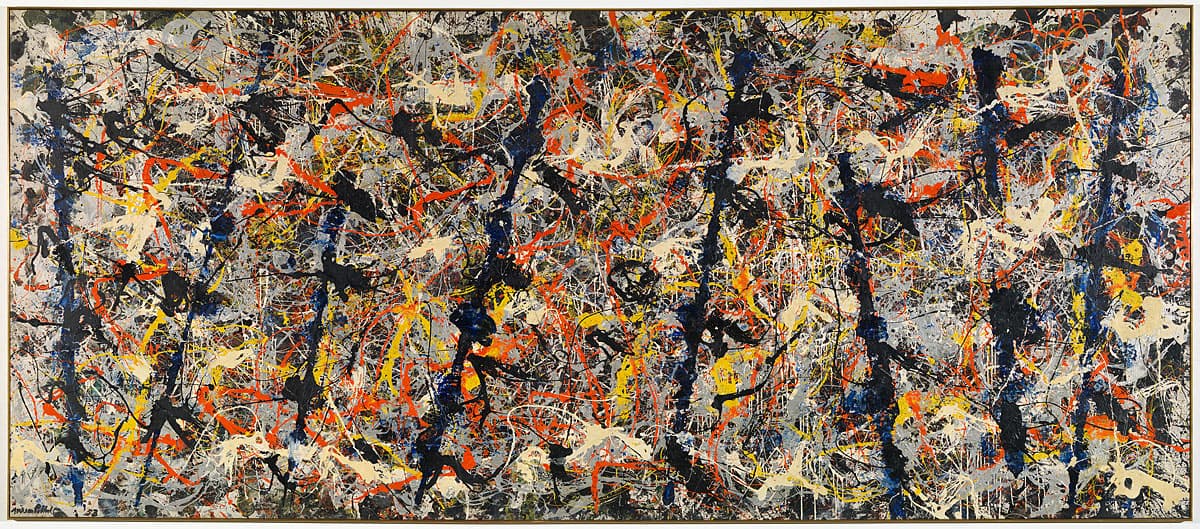

Jackson Pollock

Learn moreBlue poles 1952

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1973

More detail | PermalinkBlue poles 1952 is one of the most famous paintings in the Gallery’s collection. First exhibited at Jackson Pollock’s solo show at Sidney Janis Gallery in 1952, where it was listed as Number 11, 1952,[1] it was later titled by the artist Blue poles.[2]

In 1973 Stanley P Friedman wrote an article in the New York Magazine in which he reported being told by Tony Smith that he and Barnett Newman had painted on the canvas that subsequently became Blue poles.[3] No-one who Friedman interviewed for his article refuted the possibility that Smith or Newman contributed to the early stages of the work. What they all denied emphatically is that these initial exercises contributed in any way to the work that Pollock then built up on the canvas to become Blue poles—any trace of earlier involvement by Smith or Newman was covered over by the painting that Pollock subsequently made on the canvas.

The first layer of paint was applied, as had been customary practice for Pollock since 1947, while the canvas was stretched out on the floor.[4] The earliest visible layer of paint is black, thinning at the edges to a green, which appears to have been formed by the mixing of yellow and black, embedded with fragments of the glass basting tubes that were used to apply the first layers of paint to the canvas. Subsequently the unstretched canvas was tacked to a beam that ran along the wall of the studio; liquid white paint was then applied and allowed to run down.

For Pollock’s next campaign the canvas was returned to the floor. Using his characteristic method of pouring fluid paint in a continuous stream onto the canvas from above, employing sticks, dried brushes and syringes, Pollock built up a web of rhythmic linear accents using yellow, orange and aluminium paints. He then left the canvas to dry. When he next worked on the painting he added in the blue poles, apparently using a ‘2 x 4’ length of timber as a straight edge,[5] creating unusually definite forms in the ‘all‑over’ configuration of the work. Various figurative connotations have been attributed to them—from totems to the swaying masts of tall ships.[6]

Pollock integrated the poles by lacing them into the composition with fine dripped skeins of white, black and blue paint. In this final operation the artist used brushes and rags as well as poured paint. Careful adjustments were made, such as fastidiously painting over a thin white dripped line at the left edge of the canvas in black. In many respects, the approach in Blue poles is similar to Pollock’s earlier works; the painting is built up with successive layers of dripped and poured paint evenly dispersed across the canvas. However, it also differs in a number of important ways, not least of which are the strong vertical elements of the ‘poles’. This departure was both a reprise of a recurrent motif in Pollock’s work and a self-conscious re-evaluation of the painting technique for which he was famous.

Anthony White[7]

[1] Although the date of the painting is definitely 1952, Pollock appears to have mistakenly dated it ‘53’, then painted over the ‘3’ to a ‘2’.

[2] Sidney Janis, correspondence with the National Gallery, 17 January 1986. Pollock himself referred to the painting as Blue poles in a conversation with BH Friedman in 1955, see BH Friedman, Jackson Pollock: Energy made visible, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1972, p xvii.

[3] Stanley P Friedman, ‘Loopholes in “Blue Poles”’, New York Magazine, 29 October 1973, pp 48–51.

[4] The canvas is high‑quality Belgian linen with a commercially oil‑primed ground.

[5] Lee Krasner Pollock recalled seeing this piece of wood near the painting covered with wet blue paint, see Francis Valentine O’Connor and Eugene Victor Thaw, Jackson Pollock: A catalogue raisonné of paintings, drawings and other works, 4 vols, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1978, vol 2, p 193.

[6] In his biography of Pollock, Bryan Robertson attributes both connotations to the poles, and also suggests a cruciform and an anchor; see Bryan Robertson, Jackson Pollock, Thames & Hudson, London, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1960, pp 23–4.

[7] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 240–5.

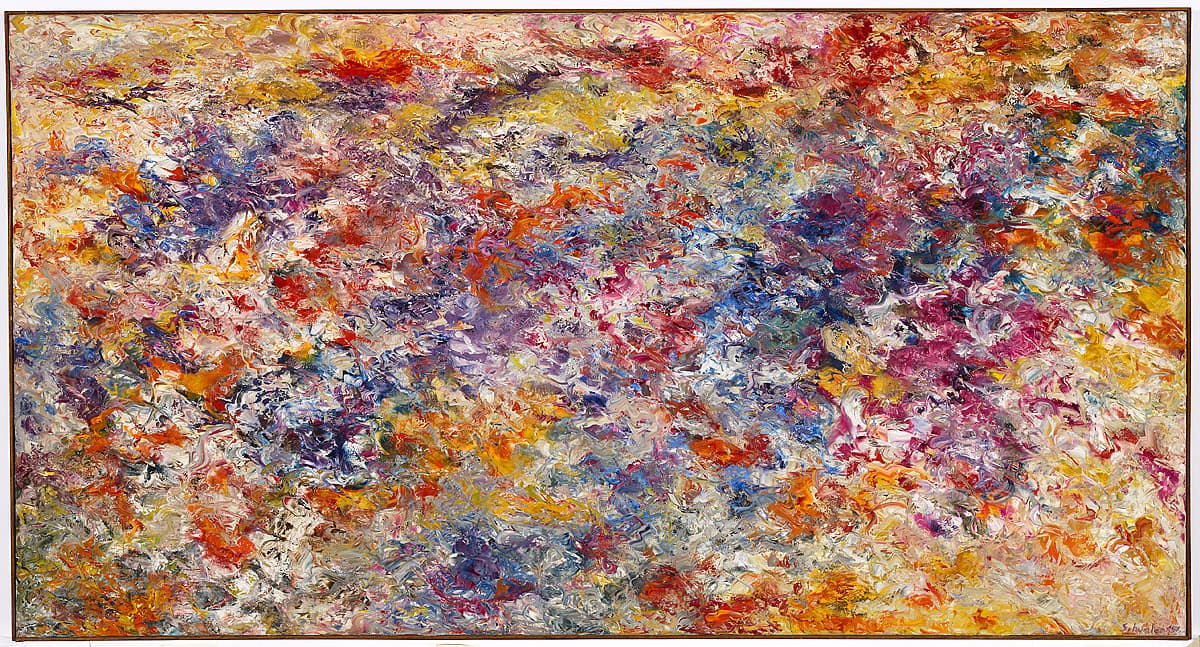

Lee Krasner

Learn moreUntitled 1953

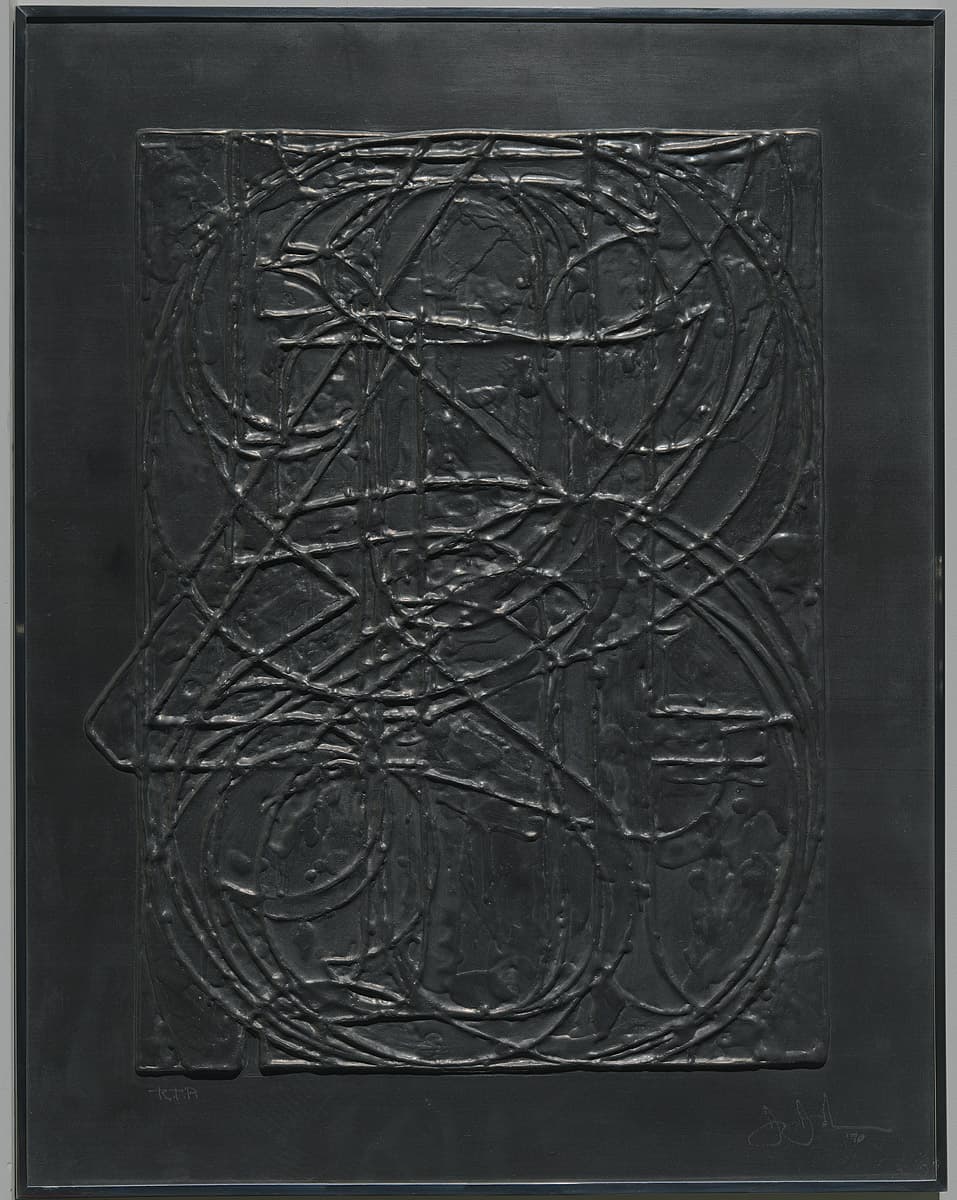

© Lee Krasner. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1983

More detail | PermalinkFrom 1937 until 1940 Lee Krasner attended classes at the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts, New York. She joined the American Abstract Artists group in 1940 and exhibited for the first time in their fourth annual exhibition in New York that year. Between the late 1940s and the mid 50s, Krasner’s work went through several experimental and transitional phases. In her painted canvases of the late 1940s, known as the ‘Little pictures’, her surfaces were comprised of small, geometric and hieroglyphic elements applied in thick multicoloured paint. By 1950 Krasner had returned to a semi-figurative mode—a brief yet incongruous manoeuvre that resulted in an unsuccessful exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951.

Harnessing this disappointment as impetus for change, Krasner turned to collage and, in stark contrast to her coloured canvases, produced a series of black-and-white works composed of segments of cut paper pasted on top of pre-existing drawings. The artist remembered: ‘In 1953, I started tearing up drawings, which led to collaging, and then I went into some of these canvases that had been sitting there a long time and nothing happening with them and I collaged some of these as well.’[1]

Untitled 1953 reveals a dramatically stripped-back palette and a sophisticated loosening of form. Krasner has allowed space and air to settle within the compositional activity, perhaps as a metaphorical exhale from the intensity of the works of the previous decade. The surface of Untitled is a complex combination of a base drawing executed in black oil paint applied directly onto the paper, over which several recycled pieces have been adhered. The composite surface that results is a tangle of solid black and dry scraped brushstrokes of frenetic drags, pulls and abrupt arcs, periodically sliced into sections by the sharp edges of cut paper.

The collage works of 1953 preceded a sustained period of work in this medium and numerous examples were exhibited, to critical admiration, in 1955 at the Stable Gallery, New York. Looking back on Krasner’s collage work, art critic Clement Greenberg commented that, in employing this technique, Krasner had made a major contribution to the progression of Abstract Expressionism at the time.[2] Collage became a particularly dynamic medium for the artist and she would often return to it in order to reinvigorate her processes after periods of creative pause. Through the destruction and ‘cannibalisation’ of her earlier works, Krasner was not only symbolically breaking with the past, but abruptly forcing herself to take a new direction. Indicative of a successful stylistic modification, the collage works from this period can be seen to inform the canvases that Krasner was to produce over the next few years.

Jaklyn Babington

[1] Letter from the artist, NGA file 78:0059, f 127.

[2] Ellen G Landau, Lee Krasner: A catalogue raisonné, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1995, p 146.

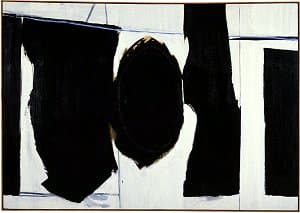

Ad Reinhardt

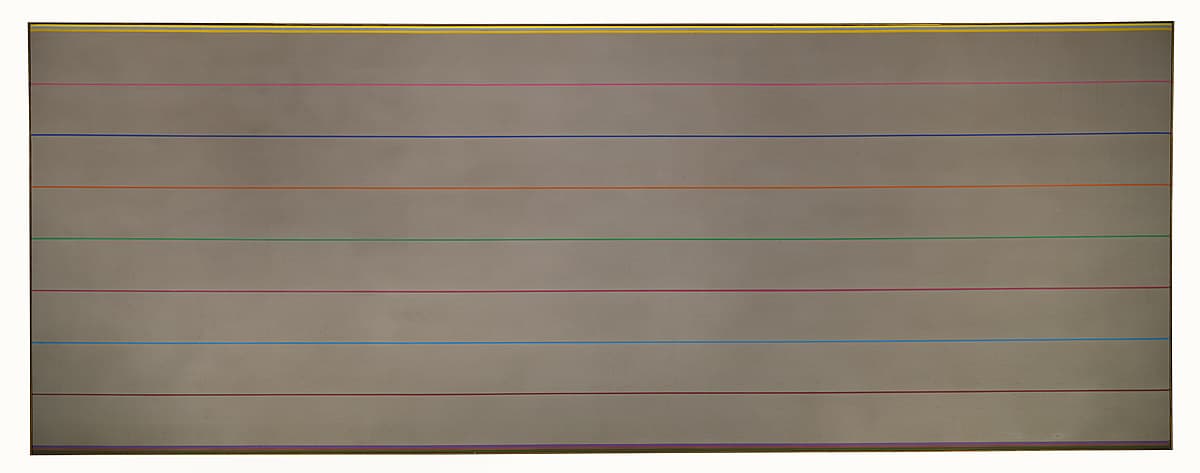

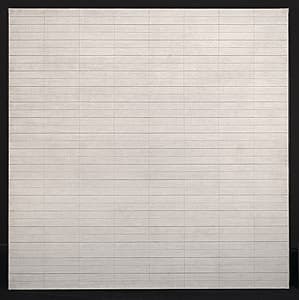

Learn morePainting 1954-1958 1954-58

© Ad Reinhardt. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1973

More detail | PermalinkThe development of Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings began in 1948 when he abandoned cursive mark-making for a geometric style. His work became increasingly formalised over the next few years, evolving into rigidly vertical and horizontal shapes in red, blue or green paintings. The trisected composition―which divided the square canvas into nine equal squares―first appeared in 1952. By 1953 Reinhardt's work was predominantly monochromatic and increasingly monotonal and, from 1955, almost exclusively black. The black paintings assumed various shapes, usually tall and narrow, but including square paintings of various sizes such as Painting 1954–58. In 1960 Reinhardt further restricted the format of his work to five-foot square (152.6 x 152.6 cm), maintaining these dimensions for the rest of his life. The severity of the artist’s paintings seems to run parallel to his uncompromising critiques of modern art, published regularly in major art journals at this time. Reinhardt described his black works as the ‘ultimate’ or the ‘last paintings’ possible, and his uncompromising approach was highly influential, especially for Minimalism and conceptual art.[1]

Painting is larger than the size Reinhardt eventually decided was ideal, but the work anticipates the final configuration, a formula the artist described as:

A square ‘neutral, shapeless’ canvas, five feet wide, five feet high, as high as a man, as wide as a man’s outstretched arms ‘not large, not small, sizeless’, trisected ‘no composition’, one horizontal form negating one vertical form 'formless, no top, no bottom, directionless’, three ‘more or less’ dark ‘lightless’ no-contrasting ‘colorless’ colors, brushwork brushed out to remove brushwork, a matte, flat, free-hand painted surface ‘glossless, textureless, non-linear, no hard edge, no soft edge’ which does not reflect its surroundings—a pure, abstract, non-objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting—an object that is self-conscious ‘no unconsciousness’ ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art ‘absolutely no anti-art’.[2]

The inscription in Reinhardt’s hand on the backing-board of the painting—‘ReinHardt 1954–1958’—is not necessarily a reliable guide to its dating. It was usual for Reinhardt to date his canvases as they left his studio for exhibition, according them the year they were first exhibited rather than the time he actually painted them. Months, even years, might elapse between the completion of a painting and its exhibition. The span dates inscribed by the artist may broadly refer to the completion of the work in that period or to continued work on the painting over that period. However, the extreme sensitivity of the surface of the black paintings (a single fingerprint can mar the entire painting) meant that Reinhardt frequently restored his works after exhibiting them. In repainting the surface he often changed the work and it has been suggested that the span dates indicate ‘that they were executed in two campaigns’.[3] The exhibition history and a second work, the only known painting with dimensions similar to those of Painting, would seem to confirm this dating.[4]

Michael Desmond and Michael Lloyd[5]

[1] Barbara Rose (ed), Art as art: The selected writings of Ad Reinhardt, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1991, p 13.

[2] ‘Autocritique de Reinhardt’, Iris Time, 10 June 1963, Newsletter of Galerie Iris Clert, Paris; reprinted in Rose, pp 82–3.

[3] Yve-Alain Bois, Ad Reinhardt, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1991, np.

[4] To date there is no firm evidence to confirm an earlier exhibition than the showing at Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles, in 1963; moreover, the catalogue checklist for an exhibition at the Jewish Museum, New York, in the winter of 1966–67, prepared with the assistance of the artist, reiterates the 1954–58 date. The other work is Abstract painting, black 1954–56, private collection, Switzerland; see Bois, np.

[5] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 274–6.

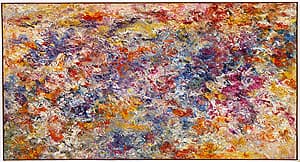

Jon Schueler

Learn moreThe first day 1956

© Jon Schueler Estate Gift of Andrew Salvesen 2010

More detail | PermalinkJon Schueler was a highly accomplished painter, although not as well-known as many other Abstract Expressionist artists. After a period in the Air Force, Schueler started painting, studying formally at the California School of Fine Arts under Clyfford Still and Richard Diebenkorn. There he also encountered Ad Reinhardt and Mark Rothko as visiting teachers. Moving to New York in 1951, Schueler met many prominent artists of the New York School, including Franz Kline, Joan Mitchell and Philip Guston.

Schueler was the first artist to have a solo show at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1957, the year it opened: The first day 1956 was included in this exhibition. Possibly the most ambitious subject ever attempted, the title refers to the creation of the Earth as narrated in the opening verses of the Bible (Genesis 1: 1–5):

1: In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth ... 4: And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. 5: And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.

Conventional Romantic depictions of the subject, such as that of nineteenth-century British painter John Martin, use deep black and blazing white to show the division of light from darkness. In contrast, Schueler renders the dazzling beauty of light as it is divided into colour. Theories about perception, the chemistry of paint and the meaning of colour become important in his realisation of such a difficult subject.

The immaterial becomes material. Blues and yellows are contrasted with hues of orange, red and purple, all made with myriad small strokes from a palette knife. The technique imbues the paint with a rhythmic, nervous quality so that the colours flicker before our eyes. The first day has rich impasto and the large canvas imparts a joyous effect, which changes according to the distance between the painting and the viewer.

Schueler’s exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery appeared to announce a new star in the firmament of the New York School. But, perhaps due to the maturing of the second generation of Abstract Expressionists—Helen Frankenthaler, Barnett Newman, Morris Louis—or the complications of his turbulent private life, Schueler’s increasingly individual trajectory of sky subjects and Turneresque Romanticism placed him outside the circle. The first day anticipates the artist’s development into a modern landscape painter of transcendent scenes.

Christine Dixon

Mark Rothko

Learn more1957 # 20 1957

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1981

More detail | Permalink1957 # 20 1957 is a canvas characteristic of Mark Rothko’s mature style, composed of soft‑edged blocks of colour that float above each other. Throughout the early 1950s he employed bright colours—reds, yellow, oranges and blues—in harmonious combinations. But in 1957, the year this work was painted, a perceptible shift occurred in Rothko's paintings. Fewer and darker colours were used, giving a sombre expression to his work. Rothko was still painting ‘dramas’, a term he had used to describe the subject of his paintings of the 1940s, using colour as the ‘instrument’. ‘I exclude no emotion from being actual and therefore pertinent,’ he said in 1957. ‘I take the liberty to play on any string of my existence. I might as an artist, be lyrical, grim, maudlin, humorous, tragic.’[1]

At that time, however, Rothko’s paintings reflected a more limited range of mood: among the ‘ingredients’ of his art listed in a lecture he delivered at the Pratt Institute in 1958, was ‘a clear preoccupation with death. All art deals with intimations of mortality’.[2] To Dore Ashton, a regular visitor to his studio at this time, Rothko claimed that ‘he was creating the most violent painting in America’.[3] Ashton interpreted this as referring to the conflict inherent in the association of colours that Rothko conceived of as the symbolic equivalents of emotions. As Rothko believed, ‘a painting is not a picture of an experience; it is an experience’.[4]

As a result, paintings such as 1957 # 20 defy interpretation, and offer instead a completely subjective experience; they elicit an emotional response from the viewer without prescribing what that response should be. The dark, hovering forms on the red background of 1957 # 20 do, however, resonate with restrained violence and menace. The ‘dark’ emotions that permeate 1957 # 20 and other paintings of 1957 were, with certain exceptions, the basis for all the works Rothko painted until he committed suicide little over a decade later.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[5]

[1] Elaine de Kooning, ‘Kline and Rothko: Two Americans in Action’, Artnews Annual, XXVII, 1958, p 177.

[2] Taken from notes made at a lecture by Rothko at the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, in 1958, and published by Dore Ashton in The New York Times, 31 October 1958, reprinted in The New York School: The first generation: Paintings of the 1940s and 1950s, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, 1965, p 142.

[3] Dore Ashton, About Rothko, Oxford University Press, New York, 1983, p 138.

[4] Rothko, quoted in Anna C Chave, Mark Rothko: Subjects in Abstraction, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1989, p 172.

[5] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery Canberra, 1992, p 250, by Steven Tonkin.

Willem de Kooning

Learn moreJuly 4th 1957

© The Willem de Kooning Foundation, New York. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1972

More detail | PermalinkThe image of woman that had been the primary subject of Willem de Kooning’s paintings from 1950 gradually began to dissolve into the landscape. By 1955, the women had virtually disappeared, subsumed and replaced by gestural abstractions inspired by the forms of the urban landscape. These paintings, typically made with small, tightly-knitted shapes in strong primary colours, teem with horizontal and vertical marks. Those that follow show the shift of interest from city to countryside that climaxed in de Kooning’s decision to move to Springs, East Hampton, in 1961. While still living in New York, de Kooning had taken to painting occasionally in the country, often staying at the home of his brother-in-law, a house that de Kooning eventually purchased himself.[1]

De Kooning’s paintings of 1957, such as July 4th, mark a change from the preceding landscapes in the use of wider brushstrokes and enlarged, clarified areas that convey a sense of open spaces. The notion of rural landscape is suggested by the strong white horizontal band at the bottom of the painting, formed by the removal of tape protecting the white paper support. A number of paintings at this time were named after roadways, and Thomas B Hess has drawn attention to the way this ribbon of white suggests highway, bridge or horizon line.[2] Certainly this parallel may have amused the artist, for he rarely allowed so strong a feature to remain unaltered in his work. No doubt this is also because de Kooning used small paintings on paper as a test bed for new ideas and accidental effects that could be incorporated into larger works. July 4th itself is built from pre-existing work; a single sheet of paper painted in oil paint is overlaid with torn pieces from another crustily painted sheet, then trimmed back to the sheet size.

De Kooning had perfected this collage approach over the previous decade. Often he would overlay sections of his paintings with drawings, incorporating them into the work, or trace areas of a work to use at a later stage. Collage allowed him to test a variety of solutions to painterly problems, each alternative on paper provoking new effects or inspiring further possibilities. De Kooning fully capitalised on the breaks in continuity of the painted surface generated by the addition or subsequent removal of collaged elements. The white strip produced by the removal of masking tape at the bottom of July 4th is a crude but startling example of this. Adding elements of an existing painting on paper on the upper half of the work produces dramatic elisions that break up the image to create new structures. Photographs of the artist in 1959 show similar painted fragments tacked together in a happy arrangement on the studio wall. July 4th initially had the sculptural facility of this loose construction, but was flattened and glued down by Elaine de Kooning to facilitate mounting and framing.[3] Like other paintings titled with calendar references made during the 1950s, the title refers to the date of completion.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[4]

[1] De Kooning‘s brother-in-law, Peter Fried, had moved to Springs in 1955.

[2] Thomas B Hess, ‘Four pictures by de Kooning at Canberra’, Art and Australia, vol 14, nos 3/4, January–April 1977, pp 289–96.

[3] As above, p 295.

[4] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 260–2.

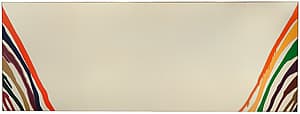

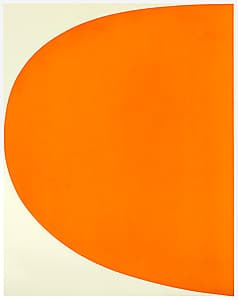

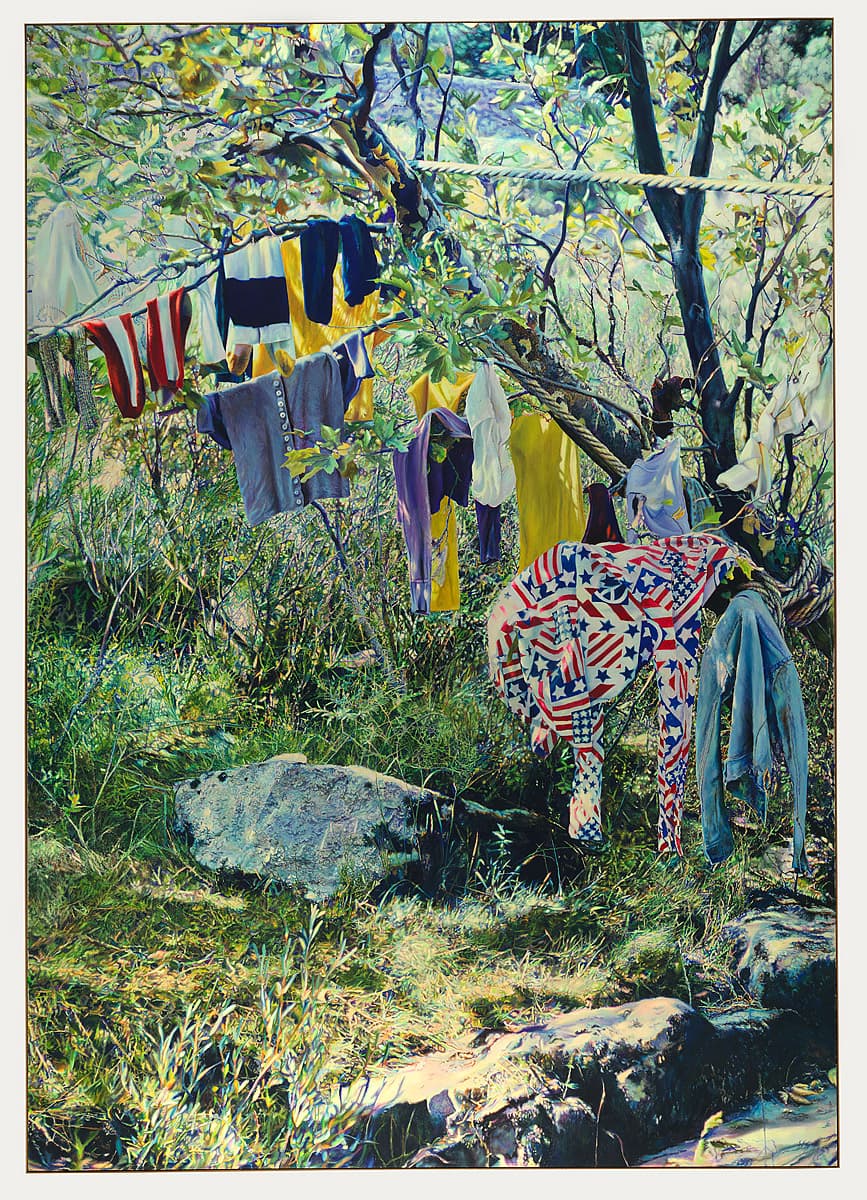

Helen Frankenthaler

Learn moreOther generations 1957

© Helen Frankenthaler Purchased 1973

More detail | PermalinkBorn in New York City, Helen Frankenthaler studied briefly with Mexican muralist Rufino Tamayo before enrolling at Bennington College, Vermont, in 1946. In 1950 she met critic Clement Greenberg who introduced her to many artists of the New York School, including Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Following a trip to Nova Scotia in Canada in 1952, during which she made many watercolour sketches, Frankenthaler began to apply diluted oil paint directly onto unprimed canvas, exploiting colour in open, lyrical compositions. This ‘staining’ technique is seen in Other generations, painted in 1957. In a statement the same year, Frankenthaler described her approach:

I often start a canvas on the floor (stretched or unstretched) then work on it on the wall ... I use sized and primed canvas or unsized cotton duck. My medium is a combination of turpentine, tube paint and enamel. I use brushes or a palette knife but I often shake or toss the paint off the brush—rather than apply it—or use my shoe or hand, controlling and changing the accidental with specific ideas.[1]

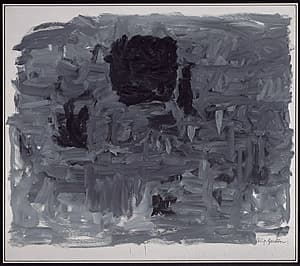

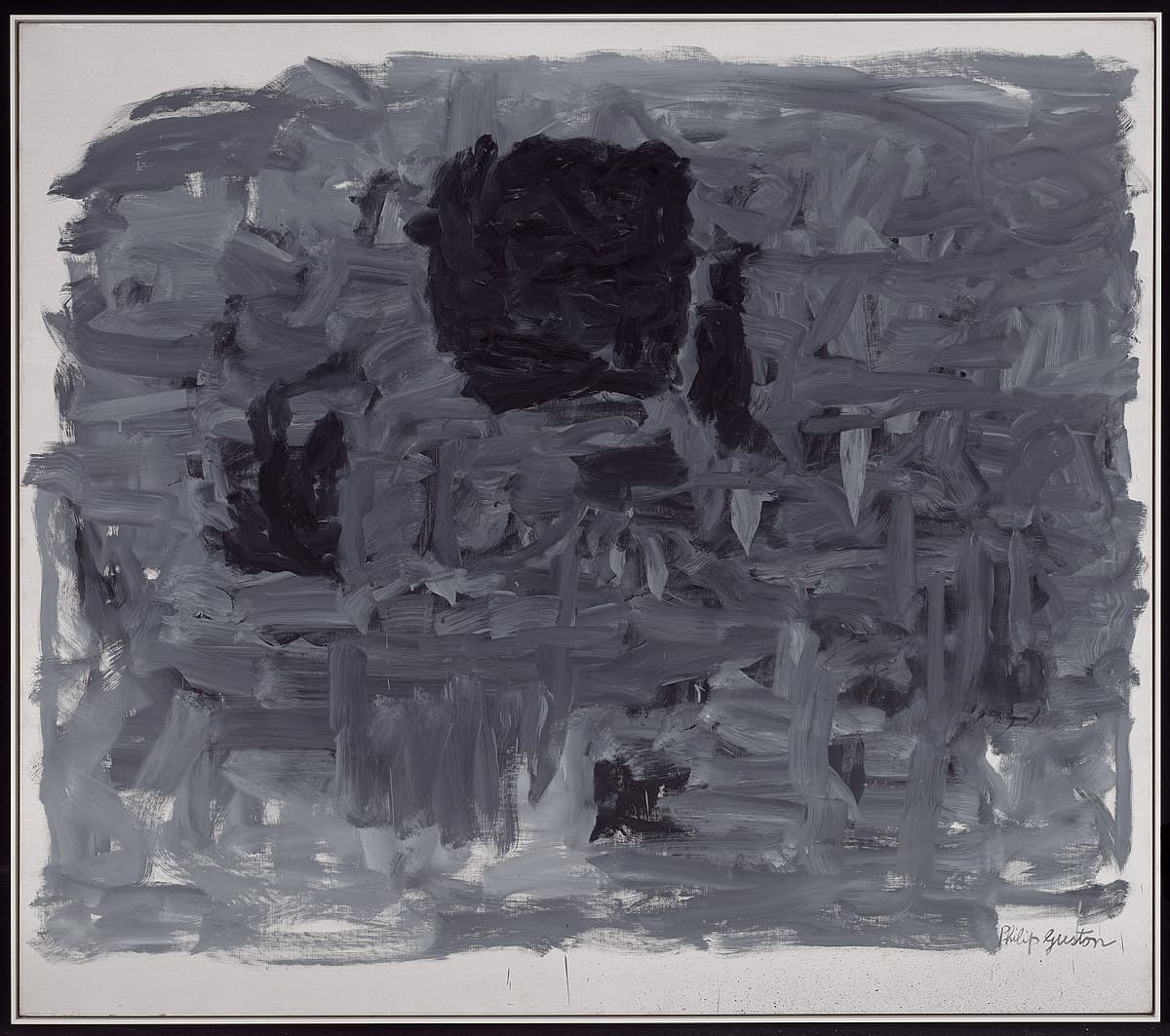

Other generations is one of a series of paintings from the autumn of 1957 that can be distinguished from Frankenthaler’s dense expressionist landscapes of 1955 and 1956 by their larger scale, open composition and gestural freedom. Vestigial images seem to surface in a number of these later paintings, for example, Jacob’s ladder 1957 and Nude 1958.[2] In this work a female torso appears to materialise in the upper centre of the painting. To a suggestion that this image may have prompted the title Other generations, the artist replied: