Figuration: Photorealism and Funk

- John Ahearn

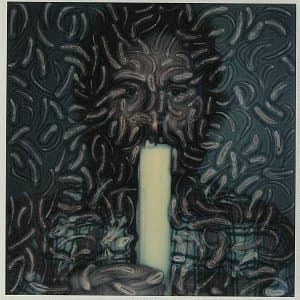

- Robert Arneson

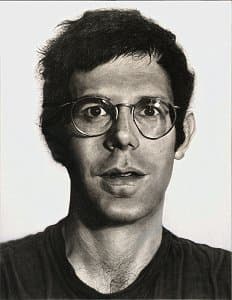

- Chuck Close

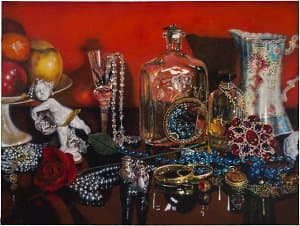

- Audrey Flack

- Franz Gertsch

- David Gilhooly

- Marilyn Levine

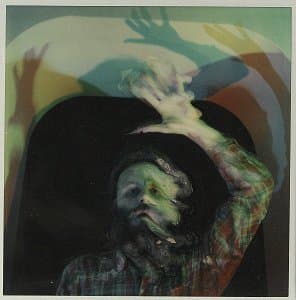

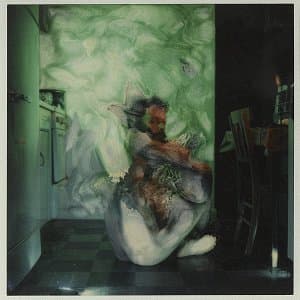

- Lucas Samaras

A return to figurative art in the late 1960s and early 1970s is often characterised as a reaction against abstract art, particularly Abstract Expressionism, Conceptual art and Minimalism. While some artists revived naturalist figuration, often imbued with the illusion of objectivity, others used photographic images in their strategy. Photorealism—also known as Super- or Hyper-realism—exhibits a photographic precision in painting or mimics actual objects. On the other hand, art that is ‘Funky’—the word was originally used in the sense of ‘smelly’—celebrates the deliberately distasteful. Funk art or Sick art are sometimes used synonymously, with Edward Kienholz held up as the Funk artist par excellence. Funk works often imply, overtly or otherwise, a criticism of concrete reality and the urban, Western world, presenting fantasy or highly coloured satire.

These new forms of Realism emerged in the 1960s out of Pop, and some of their premises are interchangeable. They are dependent on and, to an extent, develop out of photography as an art form, but take the idea of the camera’s immediacy, veracity and objectivity to its logical extreme: a lens provides a pseudo-scientific masking for the artist’s individuality. The painstaking technique of Photorealism has a long line of historical predecessors, from the verism of Dutch painting of the seventeenth century to nineteenth-century academic painting and Surrealism. Unlike earlier Realists for whom subject was paramount, for Photorealists the act of looking is of primary importance. They make themselves into visual machines, disguising their creative contribution.