Clyfford Still

Learn more1952-no.2 1952

© The Clyfford Still Estate Purchased 1978

More detail | PermalinkClyfford Still’s association with Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, and other prominent artists he met after moving to New York in 1945, led him to become known as an Abstract Expressionist or ‘action painter’, categories of which Still disapproved. More than other members of the New York School, Still attempted to purge his work of literary allusions and overt graphic symbols, preferring to stress the elements of painting—colour, shape, size—and their formal relationships as his subject matter. He frequently denied any connection between the craggy forms in his paintings and the rugged western landscapes of his childhood: ‘I only paint myself, not nature.’[1] Stripped of conventional associations, he hoped the elements in his paintings could be as pure and abstract as musical notes, and indeed he compared his paintings to orchestral compositions.[2]

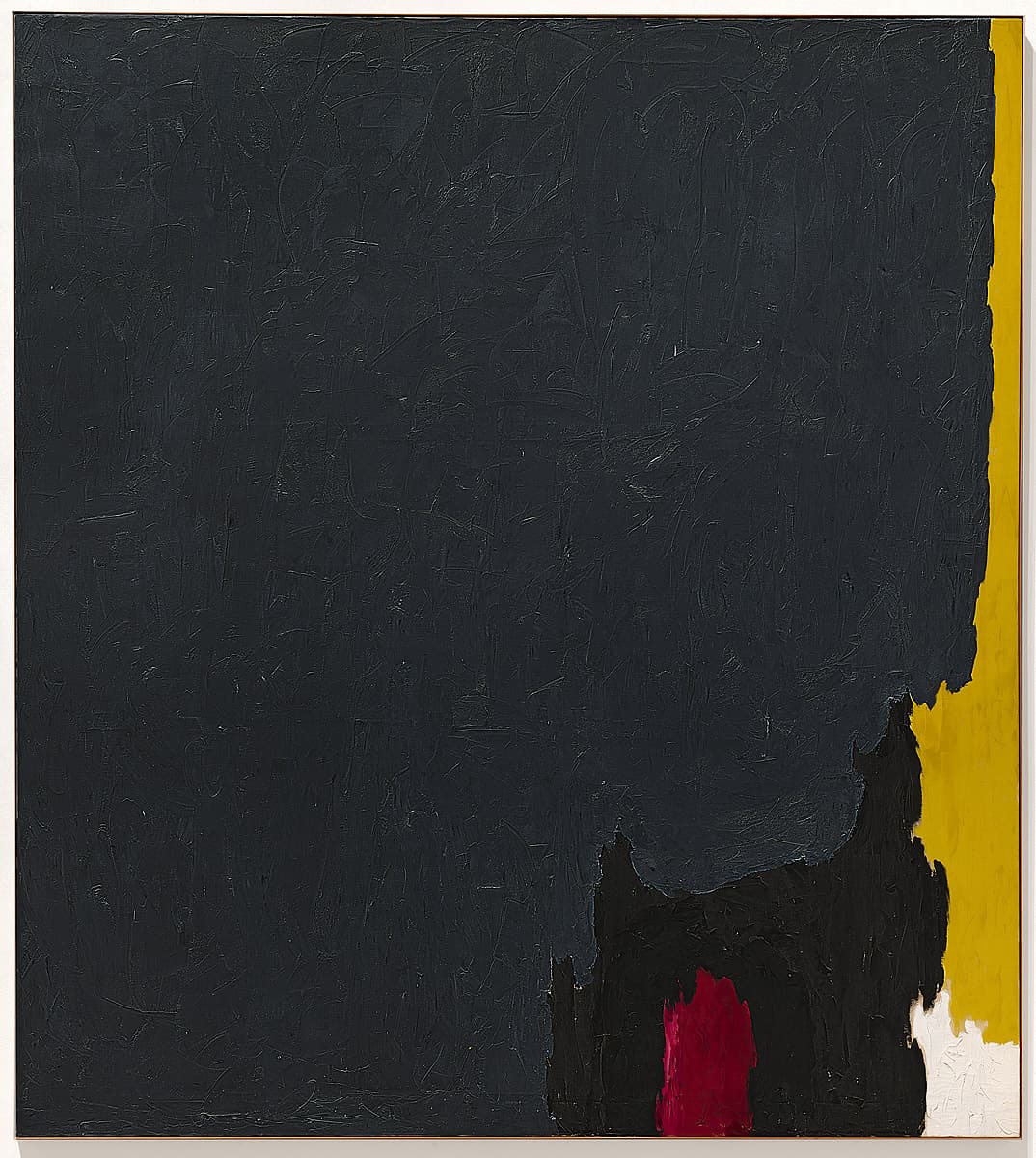

Still’s bold creation of overlapping irregular fields of colour asserts paint to be the hero of this work. Most of the canvas is covered with a dense, thickly textured veil of steel grey impasto. A leading edge of bright chrome, yellow and white allows the viewer to perceive a way out of the domineering extent of subdued grey. Another note of contrast is provided by inchoate blotches of black and red.

Despite the artist’s denial of any subject or possible narrative, he portrays a grey curtain that descends on and over the contrasting hues, seeming poised to obscure them. Still’s painting, while minimising three-dimensional and pictorial space, is deeply contemplative, sombre and introspective.

The painting was known variously over the years as Gray picture or Gray painting, however even such a mildly descriptive title would not have suited Still’s austere sensibility. ‘My paintings,’ he wrote, ‘have no titles because I do not wish them to be considered illustrations or pictorial puzzles. If made properly visible they speak for themselves.’[3] Patricia Still, the artist’s widow, has confirmed through her husband’s records that the work is correctly titled 1952–no.2 and was painted in 1952.[4] The painting is further identified by the photographic number PH–773, and is the second version of a work painted in New York in 1951. The first painting, PH–1071, which forms part of the artist's estate, was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 1979.[5] Still often made his own near-replicas of works he regarded as important, before letting them onto the art market, as he distrusted dealers, critics and museums. He wrote in 1972:

Making additional versions is an act I consider necessary when I believe the importance of the idea or breakthrough merits survival on more than one stretch of canvas, especially when it is entrusted to the precarious world of exhibitions or collecting. Although the few replicas I make are usually close to or extensions of the original, each has its special and particular life and is not intended to be just a copy.[6]

Christine Dixon[7]

[1] ‘The fact that I grew up on the prairies has nothing to do with my paintings, what people think they find in them. I paint only myself, not nature,’ from Benjamin Townsend, ‘An interview with Clyfford Still’, in Gallery Notes, Albright-Knox Gallery, vol 24, no 2, Summer 1961, pp 10–16.

[2] Maurice Tuchman, New York School: The first generation, New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, Connecticut, 1965, p 148.

[3] Clyfford Still, quoted from a letter written to the Tate Gallery in 1972, in Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s collection of modern art other than works by British artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke Bernet, London, 1981, p 710.

[4] Mrs Clyfford Still, correspondence with the Australian National Gallery, 11 August 1983.

[5] John P O’Neill (ed), Clyfford Still, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1979, cat 20, p 88.

[6] Letter, 20 July 1972, to Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, quoted in Neal Benezra, ‘Clyfford Still’s Replicas’, in James T Demetrion, Clyfford Still: Paintings 1944–1960, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, New Haven and London, 2001, pp 88–9, 98, n 12.

[7] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 265–7.