Lee Krasner

Learn moreCool white 1959

© Lee Krasner. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1978

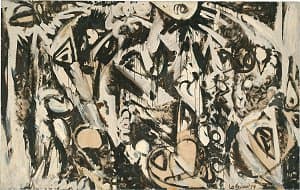

More detail | PermalinkLee Krasner’s reputation as a colourist was established early in her career. Cool white 1959, by contrast, has a sombre palette restricted to umber and white. It was painted during a difficult time for the artist, who was still coping with her grief over the 1956 death of her husband Jackson Pollock, and having difficulties with the Pollock Estate. In addition, her mother died in 1959 and an exhibition scheduled by Clement Greenberg for French and Company was cancelled.[1] Of her 1959 paintings, Krasner recalled:

I painted a great many of them because I couldn’t sleep nights. I got tired of fighting insomnia and tried to paint instead. And I realized that if I was going to work at night I would have to knock out color altogether, because I couldn’t deal with color except in daylight.[2]

Krasner began Cool white, and others from the Umber and white series, in East Hampton in 1959 and continued the series until 1962.[3] The development of The gate 1959, one of the first paintings, is recorded in photographs by Halley Erskine that show how the artist began with a biomorphic sketch, and document her progression on the work until she decided its final form.[4] The extreme monochrome palette of The gate and its explosive brushwork project a rawness and intensity which, as Ellen Laudau points out, was unprecedented in her oeuvre to date.[5] When Cool white and The gate, along with others from the series, were shown at the Howard Wise Gallery, New York, in 1960 and 1962, the energy and sheer physicality of the works was much remarked. Commentators then, as now, also noted the close connections—in size, gesture and composition—to Pollock’s work, and the ways in which Krasner seemingly took it upon herself to ‘continue’ his achievements.[6]

Cool white is dotted with staring eyes, an image that is consistent within her whole body of work.[7] Although previously suspicious of Jungian ideas of self-knowledge, Krasner allowed herself, in the process of making these works, to delve further into her identity. As she later told Cindy Nemser, ‘My painting is so biographical, if anyone can take the trouble to read it.’[8] Laudau summarised the impact of Cool white and other works from the series:

By using these pictures as vehicles to express the ongoing, and to all appearances death-defying, continuity of her tempestuous relationship with Pollock, Krasner exposed in a particularly poignant way the deeply personal roots of her artistic impulse. In the process, she produced a dramatic set of canvases whose mythic, explosive quality vividly projects her turmoil and inner rage.[9]

If the colour of these paintings was sombre, their execution was anything but subdued. As Barbara Rose observes:

No grid of compartments confines the raging energies that animate the brush loaded with thick paint, now slapped or dragged across the canvas, leaving a trail of flaring drips and sputtering comet‑like flashes of paint. The all-over images and glazed transparencies of these works suggest wind‑whipped storms or glacial events.[10]

Towards the end of the series, Krasner began to introduce a small amount of reddish-maroon and, when she started to work again in natural light, her boisterous re-adoption of colour signalled new beginnings and new concerns.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[11]

[1] Cindy Nemser, ‘A conversation with Lee Krasner’, Arts Magazine, vol 47, no 6, April 1973, pp 43–8.

[2] Richard Howard, ‘A conversation with Lee Krasner’, Lee Krasner Paintings 1959–1962, Pace Gallery, New York, 1979, p [3].

[3] The series was also called ‘Ahab-coloured’ after Krasner and Pollock’s brown poodle, who was Krasner’s constant companion at the time; Richard Howard, Krasner’s dealer, and his friend Sanford Friedman assisted the artist in choosing many of the titles of the paintings.

[4] Private collection; for one of Erskine’s photographs, dated to July–August 1959, see Ellen G Landau, Lee Krasner: A catalogue raisonné, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1995, fig 29, p 314.

[5] As above, p 181.

[6] As above, p 182.

[7] Most dramatically in Night watch 1960, private collection, where ‘the eyes’ are scattered across the entire canvas.

[8] Cindy Nemser, ‘The indomitable Lee Krasner’, Feminist Art Journal, Vol 4, no 1, Spring 1975, p 5.

[9] Laudau, p 182.

[10] Barbara Rose, Lee Krasner: A retrospective, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1983, p 122.

[11] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American paintings and sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 298–9, by Lucina Ward.