Audrey Flack

Learn moreJolie madame [Pretty woman] 1973

© Audrey Flack Purchased 1978

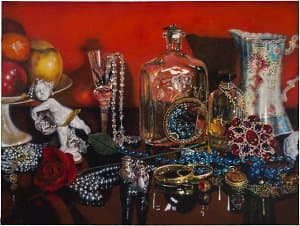

More detail | PermalinkAudrey Flack sets up the still lifes for her paintings in much the same way as a Dutch seventeenth-century painter, carefully arranging and balancing the objects until she achieves a rigorous unity of composition. Using complex and highly-controlled lighting she takes as many as 150 photographs before selecting those suitable to create a painting. As soon as the still life arrangement is suitably documented, the artist dismantles it, a process ensuring that the images, rather than the objects themselves, form the basis of her paintings. The selected photograph is projected onto the canvas, thus achieving the correct scale and eliminating the need for preliminary drawing or sketches leading up to the finished work. Flack then uses an air brush to work over the image with films of colour.

Jolie madame 1973 presents the world as seen through the camera lens. The slight blurring of some objects refers directly to the painting’s origins in a blown-up photograph. Flack acknowledged her modus operandi as early as 1964 and, although many other Photorealists apply similar aids, her admission of working directly from slides and colour prints revived controversies about the role of secondary source material. In the early 1970s she drew on photographs from her own family album and then magazine photographs of public figures. Later, in series such as Gray border 1974–75 and Vanitas 1976–77, Flack manipulated stereotypes of art and femininity.[1] Although identified as a Photorealist, the artist associates the movement with cool, tough, masculine symbols and positions herself as separate to it. Indeed, Flack rejects the ‘male approach to painting’, preferring instead to concentrate on images that represent an intimate, often female view of the world. She admits a personal involvement with her paintings and the objects portrayed within.

Jolie madame is one of the first paintings in which Flack examined the ‘time-binding potential’ of objects and elaborated the formal possibilities of still life on a monumental scale.[2] This large, baroque painting assaults the senses with its lush, opulent surface and warm, sensuous tones, the halos of glazed-on colour. The lack of hierarchy in the objects portrayed, the shallow depth of field and elements such as the use of highlights across the painting, including the jewellery in the foreground that seemingly merges with its reflections, combine to give the work an abstract quality, despite its pictorial subject matter. Jolie madame may be easily ‘read’—as with the label on the perfume bottle that gives the work its title—but is not readily scrutinised. Flack had created all-over compositions from multiple objects in 1972–73—including close-ups of sundaes, cakes and tarts—before reverting to complex still lifes.[3] By placing a profusion of her own objects in an intimate setting, and by declaring her involvement with them, Flack creates in Jolie madame an exuberant and entirely joyous affirmation of her own personal, and female, existence.

Lucina Ward[4]

[1] See, for example, Katherine Hauser, ‘Audrey Flack’s still lifes: Between femininity and feminism’, Woman's Art Journal, vol 22 no 2, Autumn 2001/Winter 2002, pp 26–30, at http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358899, accessed 11 April 2018.

[2] Lawrence Alloway, ‘Introduction’, in Audrey Flack on painting, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1981, pp 26–7.

[3] In subject matter, scale and composition, Jolie madame is related to? works such as Chanel 1974 (collection Mrs Morton G Neumann, Chicago) and Grey border series such as Buddha 1975 (Saint Louis Art Museum) and Leonardo’s lady 1975 (Museum of Modern Art, New York).

[4] See also Kay Vernon, ‘Audrey Flack’, Genesis of a Gallery part 2: A touring exhibition from the collection of the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1978, p 79.