Dan Flavin

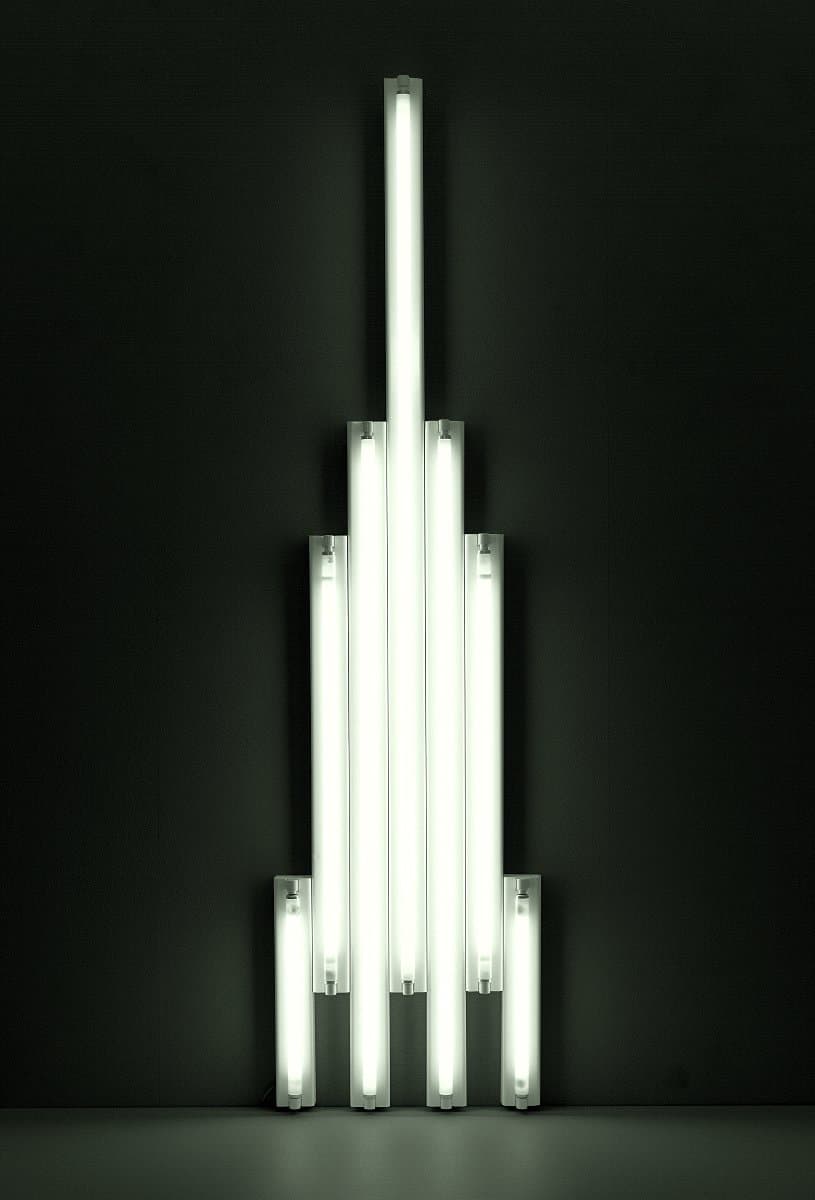

Learn moremonument to V. Tatlin 1966-69

© Dan Flavin. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1978

More detail | PermalinkDan Flavin first began using electric lights in his work in 1961, and by 1963 was making works using fluorescent light exclusively. His monument to V. Tatlin 1966–69 is one of a series of sculptures using standard‑length fluorescent tubes. There are 39 variations within the series, each in an edition of five; all use varying standard-sized white fluorescent light tubes set adjacent to each other, arranged in different configurations, most often vertically, as well as horizontally and diagonally.[1] The series memorialises artist and revolutionary Vladimir Tatlin, ‘who dreamed of art as science [and] stands, a vibrantly aspiring order, in lieu of his last glider which never left the ground’.[2] Flavin admired Tatlin as an ‘unassuming, artist-engineer’ who desired the unity of art and technology, away from the confines of art institutions that separate art from ‘daily concerns’.[3] The American artist’s interest was prompted by a book on Russian avant-garde art by the dancer and art historian Camilla Gray Prokofiev.[4]

The use of the term ‘monument’ in the title―which alludes to Tatlin’s most ambitious, though never realised, architectural project, Monument to the Third International 1921―is intended as ironic; the fragile fluorescent tubes present an antithesis to the solidity and perceived permanence of bronze or stone traditionally used in monumental sculpture. To emphasise this point Flavin insisted that ‘monument’ use lowercase letters. His ‘monument’ is, moreover, human in scale and domestic in references. As Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe points out, fluorescent tubes are constructed to architectural conventions which are, in turn, derived from the height of an average person.[5] Flavin’s use of this form of light, once familiar and mass-produced but now increasingly rare, is an instance of obsolete technology. Fluorescent light―produced by an electrical charge through the gas and mercury contained within the tube, and its fluorescence on the phosphor-coating on the inner surface of the glass―and the tubes are short-lived. Flavin enjoyed the humour of making temporary monuments: as he commented, these monuments only ‘survive as long as the light system is useful [approximately] 2,100 hours’.[6]

From four ‘feet’ monument to V. Tatlin thrusts upward, like a rocket or an elegant Art Deco skyscraper highlighted against the sky. When considered in sequence, the configuration of tubes in some monuments suggests an element of flight, almost as if the form might start on its vertical trajectory. Others in the group collapse on the floor, attach themselves to edges of walls or cluster in corners. Monument 1 for V. Tatlin 1964 and monument 7 for V. Tatlin 1964–65 were the first to be fabricated; others were assembled as the opportunity to exhibit presented.[7] The dating of each work refers to both the original conception in diagrammatic form and subsequent material realisation. Hence, in the case of monument to V. Tatlin 1966–69, a sketch of 1966 marks the basis for this configuration, which was fabricated in 1969. Flavin produced at least 20 sketches for the monument to V. Tatlin series between 1964 and 1970, although he claimed never to have counted the designs, and continued to produce variants until 1990.[8] The monuments to V. Tatlin remain some of his best-known works.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[9]

[1] Dia Art Foundation, New York, holds the complete [22 of the] set of monuments: see https://www.diaart.org/collection/collection/keyword/flavin%20monument%20for%20tatlin/page/2#flavin-dan-monument-for-v-tatlin-1966-1980-013, accessed 22 February 2018. Other examples include: monument 1 for V. Tatlin 1964, Museum of Modern Art, New York; monument to V. Tatlin 1966, Philadelphia Museum of Art; and monument for V. Tatlin 1969, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

[2] Dan Flavin, ‘The artists say’, Art Voices, vol 4, Summer 1965, p 72.

[3] Letter from Dan Flavin to Ronald Alley, dated 12 April 1972, quoted in The Tate Gallery’s collection of modern art other than works by British artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke Bernet, London, 1981, p 219.

[4] Camilla Gray, The great experiment: Russian art 1863–1922, Thames & Hudson, London, 1962. rf also letter, 12 April 1972: mention of Gray?

[5] Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe, ‘Space and speed in Flavin, Minimalism, Pop art and Mondrian’, in Jeffrey S Weiss and Briony Fer (eds), Dan Flavin: New light, Yale University Press, New Haven and National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2006, pp 82–107, at p 99.

[6] Quoted in Michael Govan, ‘Irony and light’, in Dan Flavin: A retrospective, Dia Art Foundation, New York, National Gallery of Art, Washington, and Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007, pp 19–108, at p 45.

[7] monument 7 for V. Tatlin 1964–65 was shown at the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute of Contemporary Art in May 1965.

[8] As Flavin explained, ‘I've never counted the designs. Perhaps, I will not draw more ... I believe that there is one diagram for 1965, one for 1966, none in 1967 and so forth. The last, at present, is of 1970.’ Quoted at tate.org, accessed 22 February 2018.

[9] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures in the Australian National Gallery 1870–1970, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 358–60, by Steven Tonkin and Lucina Ward.