Keith Sonnier

Learn moreUntitled 1969

© Keith Sonnier. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1976

More detail | PermalinkKeith Sonnier trained as a painter but subsequently created three-dimensional works using materials such as latex, plastic, wire mesh, glass and fabric. Rather than using traditional fine art media he experimented with materials created for industrial and commercial purposes, and in 1968 he found a medium that allowed him to draw with light: neon tubes. The use of light itself to create art became popular in the 1960s and was, in many ways, a natural choice for an artist who as a child was transfixed by lit billboards looming through the Louisiana fog and settled in New York, the light-saturated city that ‘never sleeps’.[1]

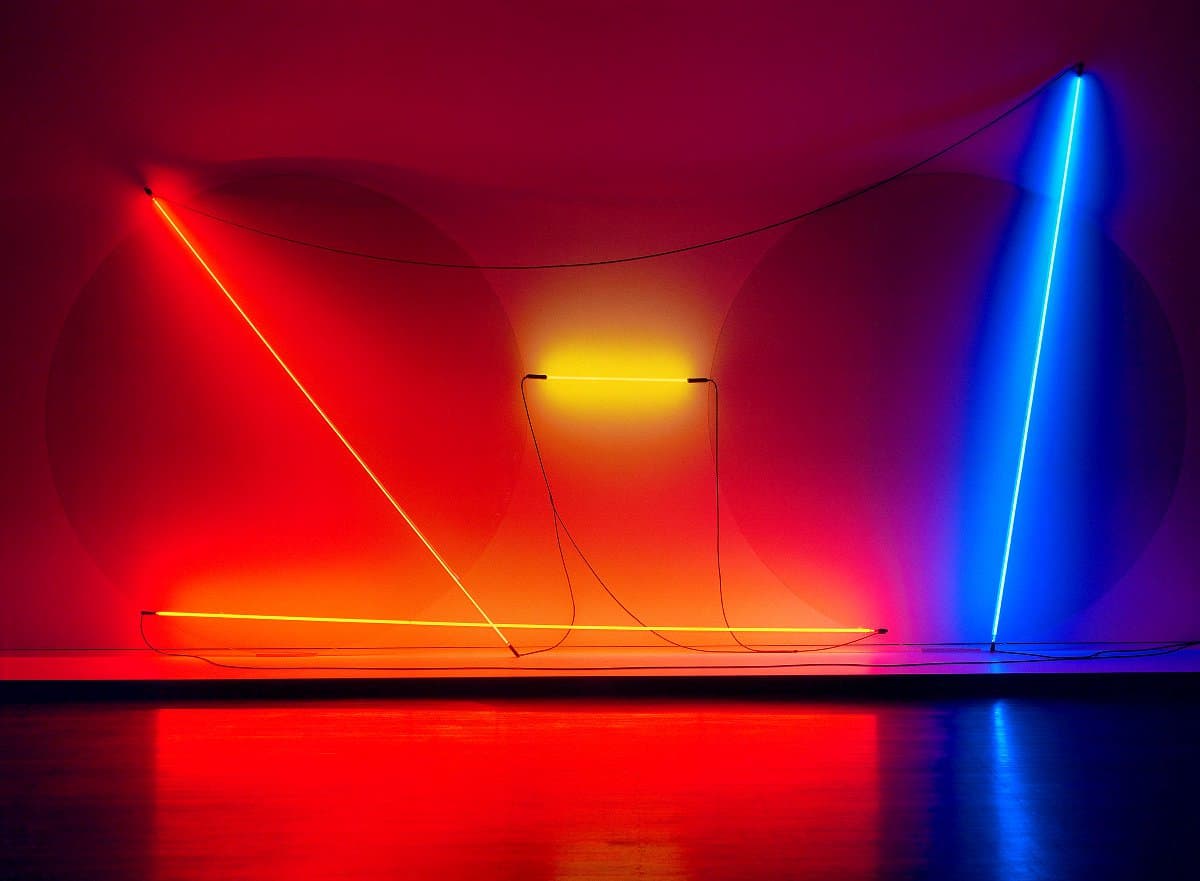

Untitled 1969 consists of two upright, but rakishly tilted, and two roughly horizontal neon lights. These are arranged over, under and between two large, round sheets of glass that lean against the wall. The elements are unified by a loose web of black electrical cord that draws the composition together. Unlike his contemporaries, Sonnier ‘draws’ with light. He uses a commercially-oriented technology to create surprisingly organic compositions; not formally arranging fluorescent tubes like Dan Flavin, nor creating apparently hard forms out of light as James Turrell was at the time, nor writing with it like Bruce Nauman, although some of Sonnier’s works do have a calligraphic flavour.

There are two layers to the sculpture: the hard forms of the glass sheets, lights and cords; and the aura of coloured light that emanates from and reflects off it. A viewer can see where the work starts, but its edges are blurred, contained only by physical barriers such as walls, or a more powerful source of light. This has the effect of recruiting viewers themselves, who are drawn into the work, bathed in its light and reflected in the glass sheets.

Untitled is an early work from Sonnier’s Ba-O-Ba Series of works made from neon tubes and sheets of glass. Beginning as props for video works, the Ba-O-Bas have been revisited by the artist for decades, including Ba-O-Ba Berlin 2002 and Ba-O-Ba Lever House 2009 in New York, both of which use neon lights and existing glass architecture to create immersive experiences. In 1998 Sonnier described how when he started working on the series he had recently been to Haiti, and was fascinated to find that the Creole language of the Haitians was very similar to the Louisiana Creole with which he had grown up: BA-O-BA ‘is a corruption of a Haitian term … basically about moonlight on the skin. It’s a very romantic, erotic sort of thing’.[2]

Such a sensual and evocative term seems at odds with Sonnier’s abstraction, as well as his medium; light has a purity about it and its use seems an extension of the impetus that drove artists like Mark Rothko to explore the use of colour and the reactions of the senses, without conceptual guidance from representational forms or suggestive titles. Poetic allusions notwithstanding, in the end the viewer is left to bathe in the moonlight alone, and to draw his or her own conclusions.

Bronwyn Campbell

[1] Calvin Harlan, ‘Keith Sonnier: an interview’, Parachute, March 1977, p 28; Keith Sonnier, Richard Shiff, Pace Gallery and PaceWildenstein, Keith Sonnier: Elysian plain + early works, Pace Gallery, New York, 2014, pp 12–13; and http://www.hallartfoundation.org/exhibition/keith-sonnier/information, accessed 9 March 2018.

[2] Linda Yablonsky and Robert T Buck, Keith Sonnier: Sculpture 1966–1998, Marlborough, New York, 1999, p 47.