Philip Guston

Learn moreBad habits 1970

Purchased 1980

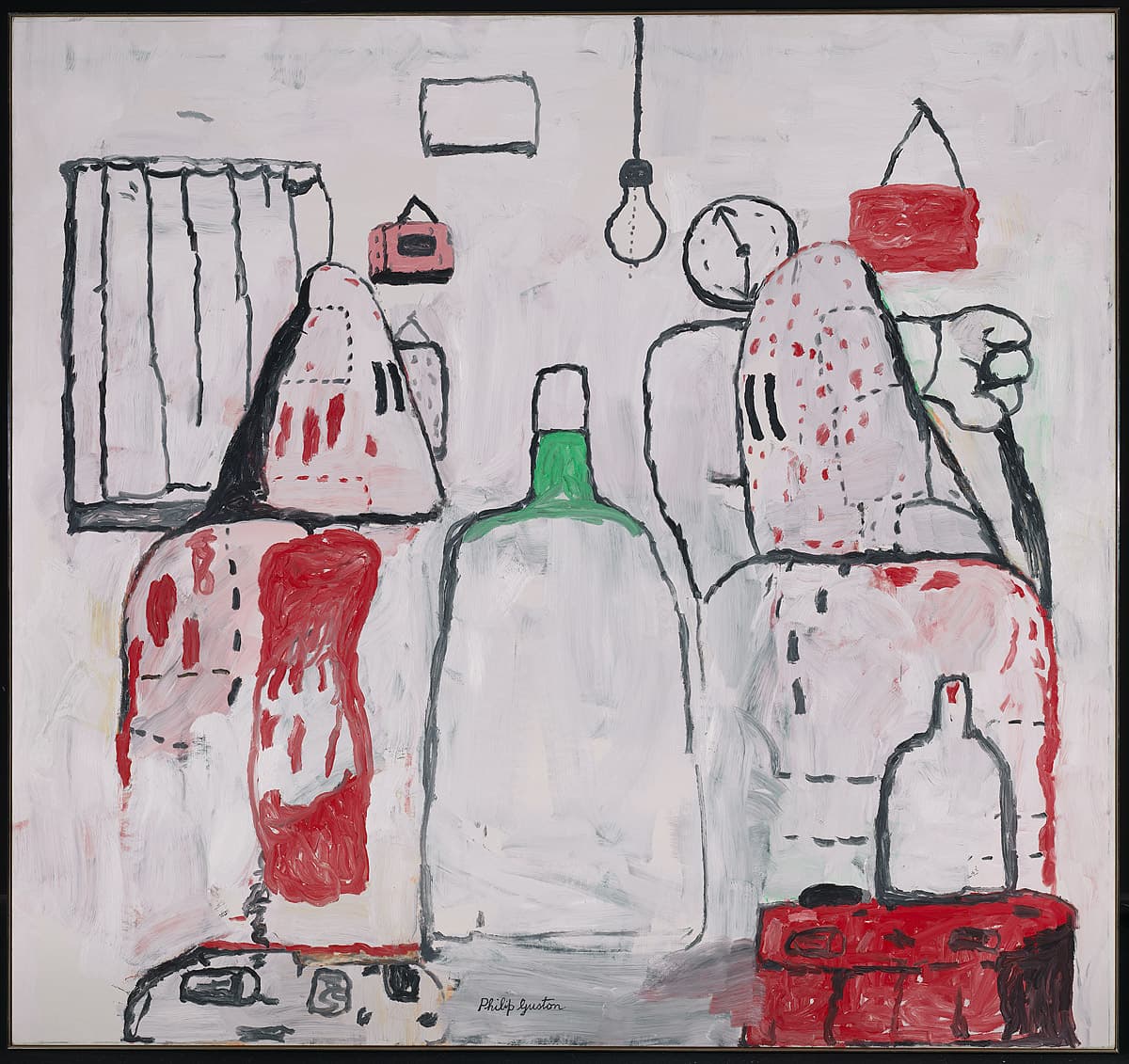

More detail | PermalinkBad habits 1970 was included in the first exhibition of Phillip Guston’s late figurative paintings held at the Marlborough Gallery, New York, in October 1970. After the delicate, painterly abstractions that had characterised his art since the early 1950s and made him one of the leading figures of Abstract Expressionism, the raw figurative paintings of the Marlborough exhibition came as a shock, not altogether welcomed by art critics. As Guston later reflected on the reception to the show, ‘It was as though I had left the Church’, and ‘I was excommunicated for a while’.[i]

In retrospect, the affinities between the late figurative paintings and his previous work are as apparent as their novelty; the inflected, creamy paint surface of his abstract paintings remains undiminished and his images re-invoke themes from his figurative paintings of the 1930s and 40s. The hooded figures that appear in the drawing City 1969 and Bad habits recall his early 1930s paintings of the Ku Klux Klan, as does the image of flagellation in the latter.[ii] Guston spoke of the relationship between his recent and earlier work in a way that illuminates Bad habits and City, describing how his involvement in radical politics, as a youth, informed his work:

In 1967–68 I became very disturbed by the [Vietnam] war and the demonstrations. They became my subject matter and I was flooded by a memory. When I was about 17 or 18, I had done a whole series of paintings about the Ku Klux Klan, which was very powerful in Los Angeles at that time … In the new series of ‘hoods’ my attempt was really not to illustrate, to do pictures of the KKK, as I had done earlier. The idea of evil fascinated me, and rather like Isaac Babel who had joined the Cossacks, lived with them and written stories about them, I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil? To plan and plot. Then I started conceiving an imaginary city being overtaken by the Klan. I was like a movie director. I couldn’t wait, I had hundreds of pictures in mind and when I left the studio I would make notes to myself, memos, ‘Put them all around the table, eating, drinking beer’. Ideas and feelings kept coming so fast; I couldn't stop, I was sitting on the crest of a wave.[iii]

Commenting on his return to figurative painting, Guston explained that after his show at the Jewish Museum in 1966, which included paintings such as Prospects 1964, he knew that wanted to deal with ‘concrete objects’. As he further explained, the visible world is ‘abstract and mysterious enough [and] I don’t think one needs to depart from it in order to make art’.[iv] Although initially disparaged by critics, Guston’s late works can be seen as a precursor to the revival of expressive figurative painting in the 1980s and are now often considered his most significant contribution to twentieth-century American art. The hooded characters gradually dispersed, replaced by, as Dore Ashton observed, a disembodied ‘naked eye’, which, along with images of a hand holding a cigarette or paintbrush, are the clearest statements of the artist’s ‘self’.[v]

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[vi]

[i] Philip Guston, quoted from a lecture at the University of Minnesota, March 1978, in ‘Philip Guston Talking’, Renée McKee (ed), Philip Guston: the late works, International Cultural Corporation of Australia, Sydney, 1984, p 56.

[ii] A whip can be seen in Guston’s first painting of the Ku Klux Klan, Conspirators c#1930 (whereabouts unknown). Flagellation was also the subject of Guston’s favourite work of art, Piero della Francesca’s The Flagellation of Christ c#1455–65, Ducal Palace, Urbino.

[iii] Philip Guston, in a lecture at the University of Minnesota, March 1978; quoted in McKee, p 55.

[iv] Philip Guston, quoted in McKee, pp 54–5.

[v] Dore Ashton, Yes, but … a critical study of Philip Guston, The Viking Press, New York, 1976, p 173.

[vi] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992 by Steven Tonkin.