Philip Guston

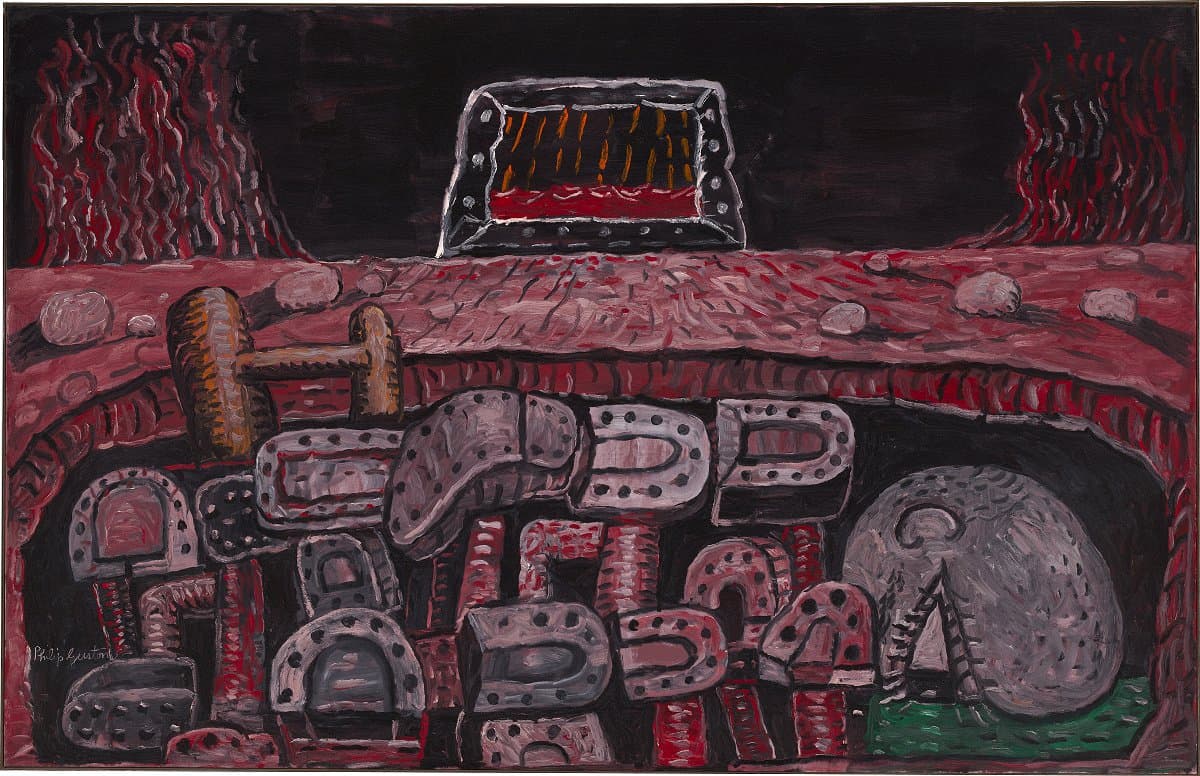

Learn morePit 1976

Purchased 1980

More detail | PermalinkCommenting on his return to figurative painting, Guston explained that after his show at the Jewish Museum in 1966, which included paintings such as Prospects 1964, he knew that wanted to deal with ‘concrete objects’. As he further explained, the visible world is ‘abstract and mysterious enough [and] I don’t think one needs to depart from it in order to make art’.[i] Although initially disparaged by critics, Guston’s late works can be seen as a precursor to the revival of expressive figurative painting in the 1980s and are now often considered his most significant contribution to twentieth-century American art. The hooded characters gradually dispersed, replaced by, as Dore Ashton observed, a disembodied ‘naked eye’, which, along with images of a hand holding a cigarette or paintbrush, are the clearest statements of the artist’s ‘self’.[ii]

Pit 1976 features this ‘naked eye’ and is one of Guston’s most powerful paintings from the mid 1970s. The work negotiates dualities through a complex layering of images and metaphors, implying that for any artist, his or her dedication to art is analogous to that of a religious belief. In Pit, the viewer’s eye is drawn toward a painting within the painting in the upper centre of the work, depicting orange rain and red water, from which a ‘light’ is emitted that parts the elemental sea of flames. In the gaping abyss below the barren surface, Guston’s ‘naked eye’ is drawn down with the tangled web of dismembered legs, which acts as a powerful metaphor for society.

The painting draws together parallel concerns of his late work, exposing his private world, a solitary existence in his studio at Woodstock, New York, to the wider social and political events impacting upon America through the 1960s and 70s. As Guston conceded:

So when the 1960s came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything―and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue … I thought there must be some way I could do something about it.[iii]

A later drawing, Key 1980, made in the months before his death from a heart attack, captures some of this sentiment: the painter works on a canvas with his back turned on a scene of jumbled, degraded humanity. Key employs similar iconography to Pit and other works of this period, in the hellish piles of rubbish and disembodied limbs, and shares an ambiguity that defies attempts to pin down a clear interpretation of the composition.

Both Pit and Key seem to reject many of the tenets underpinning Guston’s Abstract Expressionist work of the 1950s as well as the rhetoric surrounding Modernism. By acknowledging that the artist is tied to, and therefore must engage with, the wider community, Guston vindicates the radical shift of his work and the incisive social commentary that surfaces in his late figurative paintings.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[iv]

[i] Philip Guston, quoted in McKee, pp 54–5.

[ii] Dore Ashton, Yes, but … a critical study of Philip Guston, The Viking Press, New York, 1976, p 173.

[iii] Philip Guston, quoted in Jerry Talmer, ‘”Creation” is for beauty parlors’, New York Post, 9 April 1977, reproduced in Robert Storr, Philip Guston, Abbeville Press, New York, 1986, p 53.

[iv] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992 by Steven Tonkin.