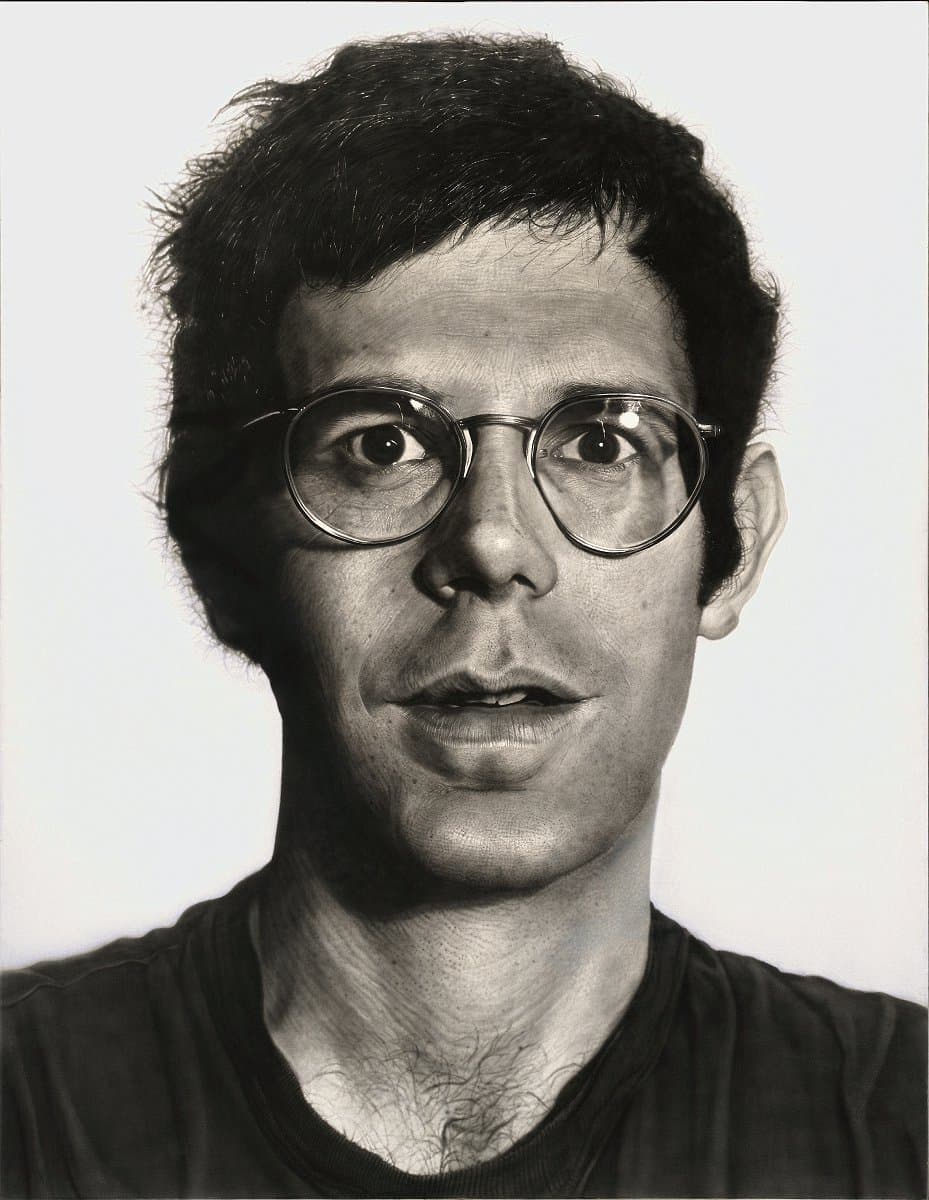

Chuck Close

Learn moreBob 1970

© Chuck Close Purchased 1975

More detail | PermalinkChuck Close’s approach to the human face has radically changed the definition of portraiture. In his early paintings he methodically and carefully reconfigured the face in a process of formal analysis, resulting in startling and detailed images. Bob 1970 is one of a series of eight large black-and-white portraits painted between November 1967 and April 1970. Bob immediately preceded Keith 1970, the last of the black-and-white series, after which Close began to use colour in his paintings.[1] Like all the black-and-white heads, Bob is painted from gridded photographs onto a heavily gessoed ground, using black paint applied with an airbrush to build up the dark tones and minimalise expressive gesture. White paint is used occasionally for the highlights, though more often the black pigment is scraped back using a razorblade or an electric eraser.

The subject is one of Close’s friends, Robert Israel, a New York based opera designer, who later recalled that although he wanted to be invited to pose, he didn’t feel it was appropriate to ask:

Chuck’s decision of who he would paint had to do not only with whether you were a friend, but with the topology of your face. And I didn’t really think it was my business to ask him if I could pose. But eventually he did ask me and Joe Zucker to pose and I recall that it was on Memorial Day that Joe and I went to a photographic studio where Chuck set up a box camera and took our pictures.[2]

Close’s sitters are frequently posed with a neutral expression. Some of his portraits can be likened to oversized passport photos, though the large scale of the paintings balances the impersonal effect and forces us to consider the individuality of the sitter. The artist does not attempt to capture his personal relationship with the subject. During the painting of Bob Close remembers this incident:

I had taken a break and was walking back into the studio. Looking at the painting, I realised that a highlight in one of the eyes was too bright. And I said, ‘Damn it, now I'm going to have to take his glasses off’. But when I realised what I had said, I pivoted on my heel and walked out leaving the lights on, the compressor on and the airbrushes full of paint. When you start believing in your own illusion, you’re in serious trouble.[3]

At much the same time he was working on the painting Bob, Close made a film portrait of Israel, Slow pan/Bob 1970 (16mm, black and white, 10 minutes), in which the slowly-moving camera minutely scrutinised areas of the sitter’s face. He used the photograph for the painting Bob again in 1973, when he made a series of four pencil and ink drawings.[4] The artist counted on photography to provide visual data that eliminated the distortion of direct vision. He used consistent photographic parameters, controlling the depth and focus of each exposure. However, this did not place him directly within the scope of Photorealism, which incorporates a concern with the vernacular iconography of mid-century America.[5] Close complicates and analyses the relationship between photography and painting. In his quest for pictorial exactitude he goes so far as to erase his hand from his art, thus removing the author from the picture.

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[6]

[1] Close began Bob in the last months of 1969 and finished it at the beginning of 1970; see William Dyckes, ‘The photo as subject: The paintings and drawings of Chuck Close’, Arts Magazine, vol 48, no 5, February 1974, p 31. Keith 1970, Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri.

[2] Lisa Lyons and Martin Friedman, Close portraits, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 1980, p 65.

[3] As above.

[4] Bob no.I/54 1973; Bob no.II/616 1973; Bob no.III/2464 1973; Bob no.IV/9856 1973, collection Mr and Mrs Paul Gotskind, Chicago.

[5] Robert Storr, ‘Chuck Close: Angles of refraction’, Chuck Close, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1998, p 40.

[6] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures in the Australian National Gallery 1870–1970, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, p 410, by Madeleine McClelland.