Jackson Pollock

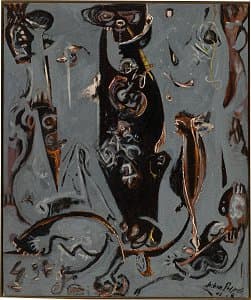

Learn moreTotem lesson 2 1945

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency Purchased 1986

More detail | PermalinkOne of the most influential artists of the Abstract Expressionist movement, Jackson Pollock’s style evolved from his early figurative work of the 1930s to the famous drip paintings of the 1950s. Pollock grew up in the American west and remained deeply interested in the sand painting ceremonies of the Navajo, which is reflected in Totem lesson 2 1945, the second of two paintings with the same title. Totem lesson 1 was completed in October 1944.[1]

The title evokes the contemporary enthusiasm for American Indian art and it has been suggested that the central motif could be a painterly variation of the Sky Father image in a Navajo sand painting illustrated in Indian Art of the United States, the catalogue of an exhibition staged at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1941. Such an image may well have been in the back of Pollock’s mind when he painted Totem lesson 2, however such influences in his work were loose and associational. Pollock said in 1944: ‘Some people find references to American Indian art and calligraphy in parts of my picture. That wasn’t intentional: probably was the result of early memories and enthusiasms.’[2]

Pollock went on to identify his fascination for French art of the twentieth century: ‘I am particularly impressed with their concept of the source of art being the unconscious. This idea interests me more than these specific painters [European émigré artists in America] do, for the two artists I admire most, Picasso and Miró, are still abroad.’[3] Indeed, Totem lesson 2 may register the impact of Surrealism.

In the final analysis, however, such comparisons accentuate the distinctiveness of Pollock’s mode of painting in Totem lesson 2. At first it comprised a large central image painted in oil, occupying most of the picture space. Before the paint was dry Pollock began editing the composition using ordinary grey house paint, paring away the central figure to a hovering spectre surrounded by swirling splinters of the original design. The normal ground‑figure relationship is reversed—the image is literally disclosed in the process of painting. Finally, returning to oil paint, Pollock animated the composition with abstract, expressive notations such as the wriggling yellow line applied directly with the tube in the upper right.

In his review of Pollock’s second solo exhibition at Art of This Century Gallery in 1945—which included both Totem lesson paintings—art critic Clement Greenberg made extraordinary claims for the 32‑year‑old artist:

Jackson Pollock’s second one‑man show at Art of This Century … establishes him, in my opinion, as the strongest painter of his generation and perhaps the greatest one to appear since Miró … Those who find his oils overpowering are advised to approach him through his gouaches, which in trying less to wring every possible ounce of intensity from every square inch of surface achieve greater clarity and are less suffocatingly packed than the oils. Among the latter however, are two—both called Totem lessons—for which I cannot find strong enough words of praise.[4]

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[5]

[1] Francis Valentine O’Connor and Eugene Victor Thaw, Jackson Pollock: A catalogue raisonné of paintings, drawings and other works, 4 vols, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1978, vol 1, p 114, cat 121. Totem lesson 1 is signed and dated lower left, ‘10‑44 Jackson Pollock’; held collection Harry W and Mary Margaret Anderson, Atherton, California.

[2] Arts and Architecture (Los Angeles), February 1944, p 14.

[3] As above.

[4] Clement Greenberg, review, Nation, 7 April 1945, p 39.

[5] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 232–5, 243–4 by Anthony White.