Jo Baer

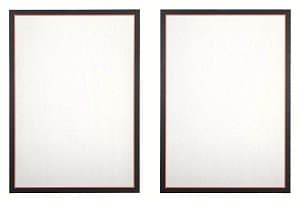

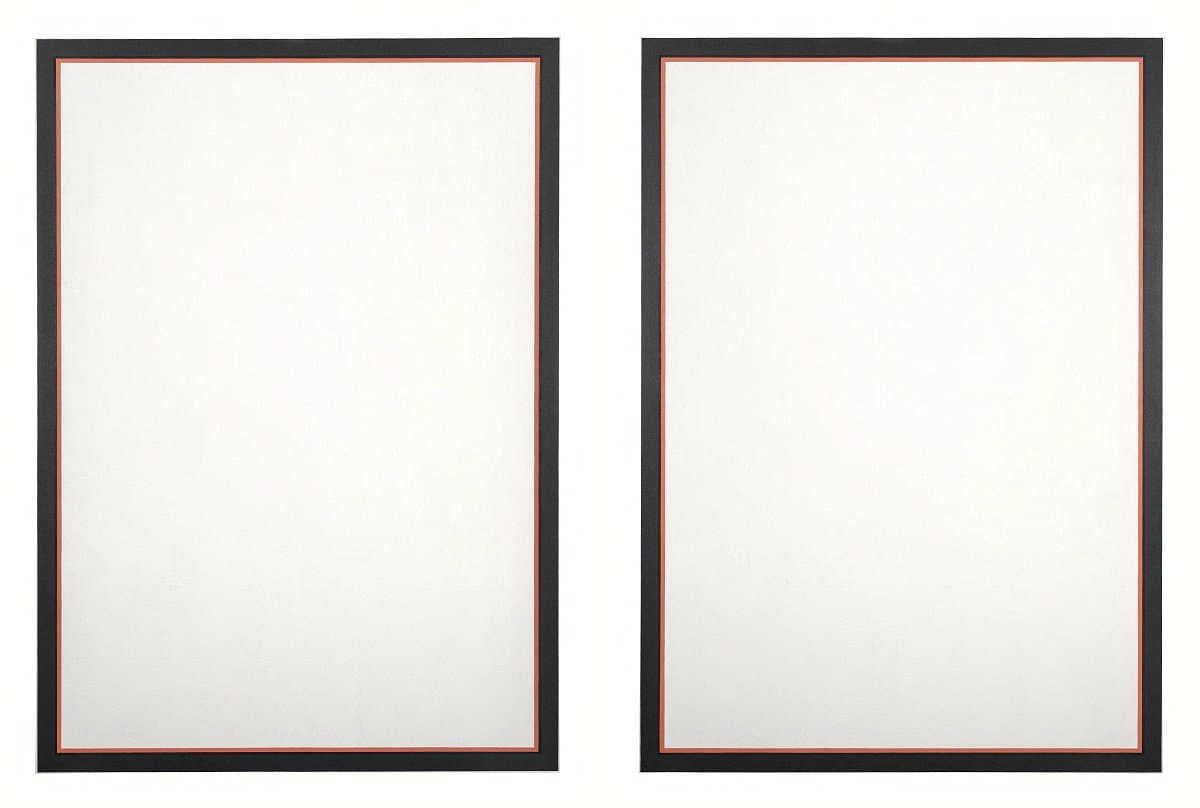

Learn moreUntitled (vertical flanking diptych - red) 1966-74

Purchased 1973

More detail | PermalinkJo Baer studied biology and art at the University of Washington, Seattle, before moving to New York in 1960. There she met Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd, becoming a key participant in Minimalism and developing her signature, reductive and hard-edge style of painting. This work was first exhibited at Documenta IV in Kassel in 1968, as Untitled (diptych) and dated 1967. In 1974, not long after the diptych was acquired by the Gallery, the artist changed the title to Untitled (vertical flanking diptych—red) and the date to 1966–74, thus locating it within a whole series of works.

Baer’s basic format for this series was well established by 1966. Each painting, or panel if the work was composite, was articulated by three colours: usually an expansive white central field, a uniform black band placed at the outer edge of the canvas, with a thin line of colour either running through the black band or striped between the black border and the lighter centre. In 1966 Baer also began to use diptych and triptych groupings, arranging them in various configurations: laid horizontally and ‘stacked’ on the wall one above the other, or hung vertically in a more ‘traditional’ arrangement flanking each other. Years later Baer described her motivation for the works:

When I was working as a minimalist painter in the 60s and 70s I used the diptych form as an iterating device, which is to say that saying something twice or more can reinforce what is meant (or for the viewer, practice makes perfect). Chasing ‘essences’, I became interested in the differences between the singular, the doubled and the many, whereupon I came to realize that single paintings objectified the unique, doubled identical ones spoke of entity, and three or more under or within one rubric implied sets, series and continuums ad-infinitum. These concepts served me well as simple thumb-rules for much of that body of work.[1]

Serial experimentation within a limited format was a typical strategy of Minimalist painters during the 1960s, and Baer was a vocal advocate of painting’s viability, particularly against the polemical criticism levelled at the medium by Judd and Robert Morris. In 1967 Morris argued that painting had become ‘antique’ as a result of its inherent and ‘inescapable illusionism’ and the divisiveness of the experience it elicited in the viewer.[2] Baer responded to this criticism both publicly and privately. In a letter published in Artforum, she asserted the primacy of painting as a radical art form, arguing that its qualities of ‘objectness’ could be as non-referential and specific on a flat plane as ‘objects’ made in three dimensions.[3]

Likewise, in private correspondence with Morris, Baer made a general claim that encapsulates her importance as both an artist and theorist of Minimalism, and resonates specifically in her Untitled (vertical flanking diptych—red):

A painting is an object which has an emphatic frontal surface. On such a surface, I paint a black band which does not recede, a colour band which does not obtrude, a white square or rectangle which does not move back or forth, to or fro, or up or down … Every part is painted and contiguous to its neighbour: no part is above or below any other part. There is no hierarchy. There is no ambiguity. There is no illusion. There is no space or interval (time). Some ‘antique’.[4]

Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond[5]

[1] Jo Baer, ‘The Diptych’, in Jo Baer: Paintings 1960–1998, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1999, p 26.

[2] Robert Morris, ‘Notes on sculpture, Part 3: Notes and nonsequitors’, Artforum, vol 5, no 10, June 1967, p 25.

[3] Jo Baer in, ‘Letters’, Artforum, vol 6, no 1, September 1967, pp 5–6.

[4] Baer, in correspondence with Morris, 29 July 1967, reprinted in ‘Annotated biography’, in Jo Baer: Paintings 1960–1998, p 40.

[5] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American paintings and sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 378–9, by Steven Tonkin.