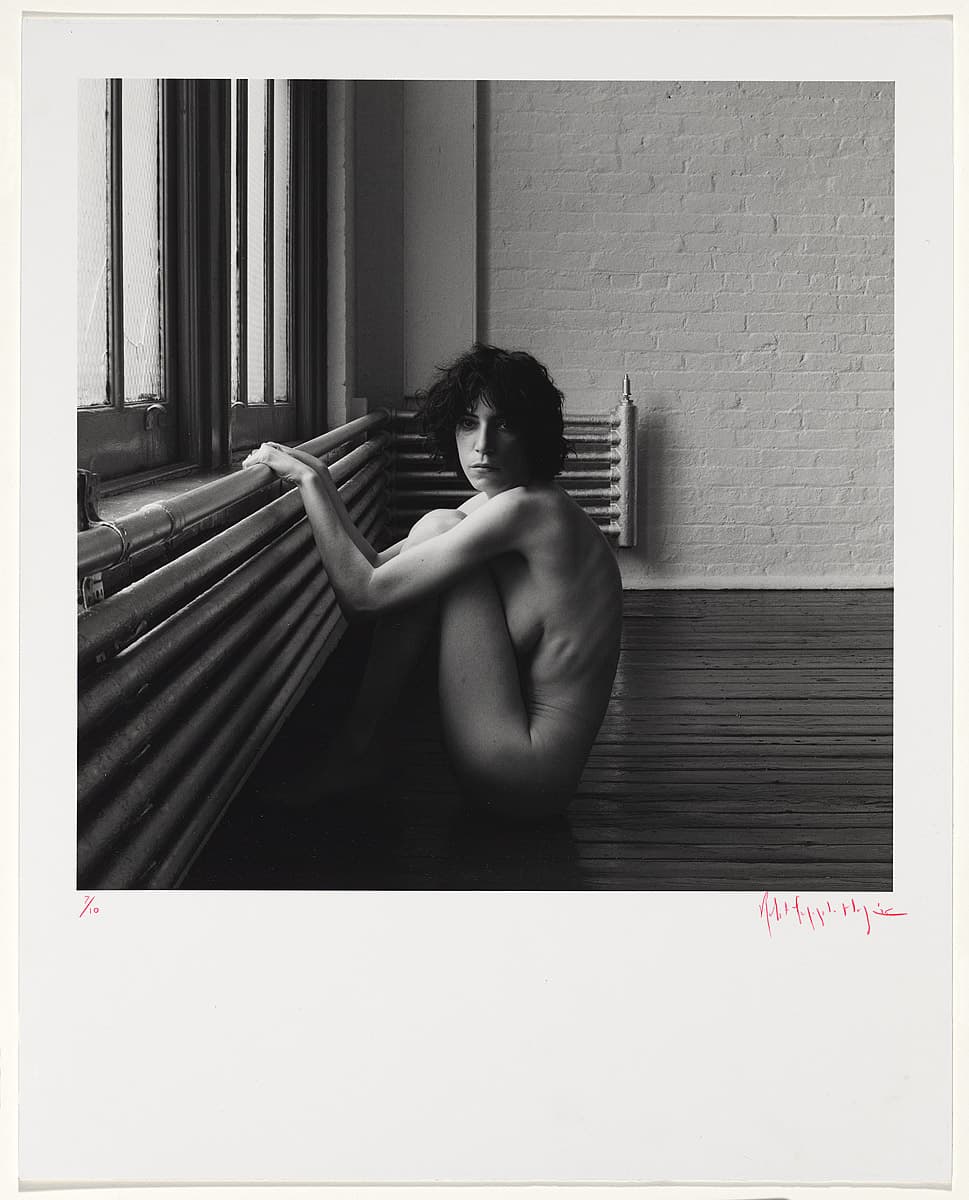

Robert Mapplethorpe

Learn morePatti Smith 1976

© Robert Mapplethorpe Estate Purchased 1980

More detail | PermalinkDuring the late 1960s, Robert Mapplethorpe made jewellery as well as boxed assemblages and collages that often featured found images, usually pornographic or religious. Around 1971, he started using his own photographs, taken with a Polaroid camera. While he never intended to become a photographer, the medium’s relative immediacy and expediency suited his disposition.[i] His first solo exhibition at New York’s prestigious Light Gallery featured Polaroids of flowers, portraits and erotic scenes. From the start, Mapplethorpe worked across a range of subjects: flower, penis and portrait were considered by him to be, formally at least, ‘the same’, with the same photographic temperament.[ii]

Mapplethorpe’s most significant work was made during the 1970s and early 80s, and his photographs engaged a very singular, direct mode with little in the way of secondary or extraneous information. The frontalism, integral to his style, brought together the flatness of his assemblages and Christian icons and the approach of American documentary photography, notably that of Walker Evans. The significance of this work, however, arises not so much from its formalism or classicism, but from the sense of intimacy that is folded into each picture. Mapplethorpe spoke about the photographic moment for him being imbued with the characteristics of a fleeting, intimate encounter, even if before or after the event there was no emotional connection: ‘I think you have to love when you are taking pictures,’ he said.[iii]

Shaune Lakin

[i] Robert Mapplethorpe, interview with Janet Kardon, in Janet Kardon (ed), Robert Mapplethorpe: The perfect moment, Institute of Contemporary Art University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1988, p 23.

[ii] As above, p 25.

[iii] As above, p 26.