Sol Lewitt

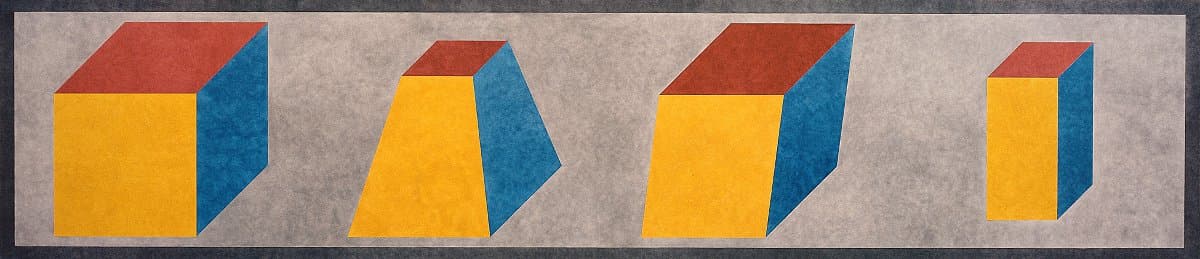

Learn moreWall drawing no.380 a-d 1982

© Sol Lewitt Purchased 1987

More detail | PermalinkA major exponent of Conceptual art, Sol LeWitt helped define the movement with his now seminal ‘sentences’ and ‘paragraphs’ published in the late 1960s.[1] His prolific output over four decades includes three-dimensional ‘structures’, drawings, prints, photographs and artist’s books, as well as nearly 1000 wall drawings. LeWitt is credited with reintroducing the wall drawing to contemporary art, a form that he described, rather frivolously, as having its origins with ‘the cave men’.[2] In wanting to make a work of art that was as ‘two-dimensional as possible’, he said it seemed ‘more natural’ to work directly on the wall than to make a construction on which to work and then put it the wall.[3]

LeWitt’s first wall drawing, an excerpt from his Drawing series II 1968, was exhibited in a group show at the Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, in October 1968. By the 1970s the artist had refined his method for realising the drawings, methods to which he adhered in the ensuing decades while exploring various kinds of lines, geometric and isometric figures, stars and continuous forms, as well as other motifs. Wall drawing no. 380 a–d 1982 consists of four isometric figures derived from a cube—the cube, a truncated pyramid (or trapezoid), a parallelepiped and a rectangle.[4] It is one of a number of wall drawings that marked a distinct shift in LeWitt’s practice, in which he drew explicit attention to the tradition of Western art since the Renaissance and to the inherent contradiction in representing three-dimensional ‘objects’ on a flat surface.

In Wall drawing no. 380 a–d the isometric figures are first drawn in pencil, over which India ink and colour ink washes are applied to define the ‘surfaces’ of the figures against a light grey background. The work is unusual in that the isometric figures are ‘framed’ by a six-inch dark grey border. In 1982, at the time of its first installation at the John Weber Gallery, New York, LeWitt responded to a question about the borders by explaining that he used darker grey to isolate the drawing from its location.[5] The ‘frame’ encourages the viewer to look into the wall drawing, accentuating the illusion of solidity of the isometric figures, yet highlighting the incongruity of the viewer’s perception, the visual deception and the flatness of the wall.

In his early writings LeWitt outlined his approach to making Conceptual art. ‘The idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work … all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand … the idea becomes a machine that makes the art.’[6] In a role analogous to an architect, LeWitt separates the conception of his wall drawings from their execution. While financial necessity meant that he, with the assistance of friends and fellow artists, undertook the installation of his early wall drawings, it was never a prerequisite.[7] Each wall drawing can be realised at different times and in different locations, then ‘de-installed’ by simply repainting the wall on which it has been drawn. As LeWitt wryly observed, ‘The wall drawing is a permanent installation, until destroyed’.[8] Or, more accurately in this case, remains an idea until installed again.

Steven Tonkin

[1] See Sol LeWitt, ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’, Artforum, vol 5, no 10, Summer 1967, pp 79–84 and Sol LeWitt, ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’, 0 to 9, no. 5, January 1969, pp 3–5.

[2] LeWitt, quoted in Andrea Miller-Keller and Sol LeWitt, ‘Excerpts from a correspondence, 1981–1983’, in Susanna Singer (ed), Sol LeWitt Wall Drawings 1968–1984, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1984, p 21.

[3] LeWitt, quoted in Lawrence Weiner, Daniel Buren, Sol LeWitt and Mel Bochner, ‘Documentation in Conceptual Art’, Arts Magazine, vol 44, no 6, April 1970, p 43.

[4] The certificate of authenticity for Wall drawing no. 380 1982 lists the figures as a cube, rectangular prism, trapezoid and parallelogram.

[5] LeWitt went on to explain: ‘It wasn’t absolutely necessary, but some inner urge (esthetic frivolity I suppose) caused me to use it.’ Quoted in Singer, p 23.

[6] LeWitt, ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’, p 80.

[7] As he explains, the artist ‘conceives and plans’ the drawing and it is realised by draftsmen: the artist can act as his own draftsman or the plan (written, spoken or a drawing) can be interpreted by the draftsman; thus ‘the artist and the draftsman become collaborators in making the art’. Sol LeWitt, ‘Doing wall drawings’, Art Now: New York, no 2, June 1971, np.

[8] LeWitt, quoted in ‘Documentation in Conceptual Art’, p 43.