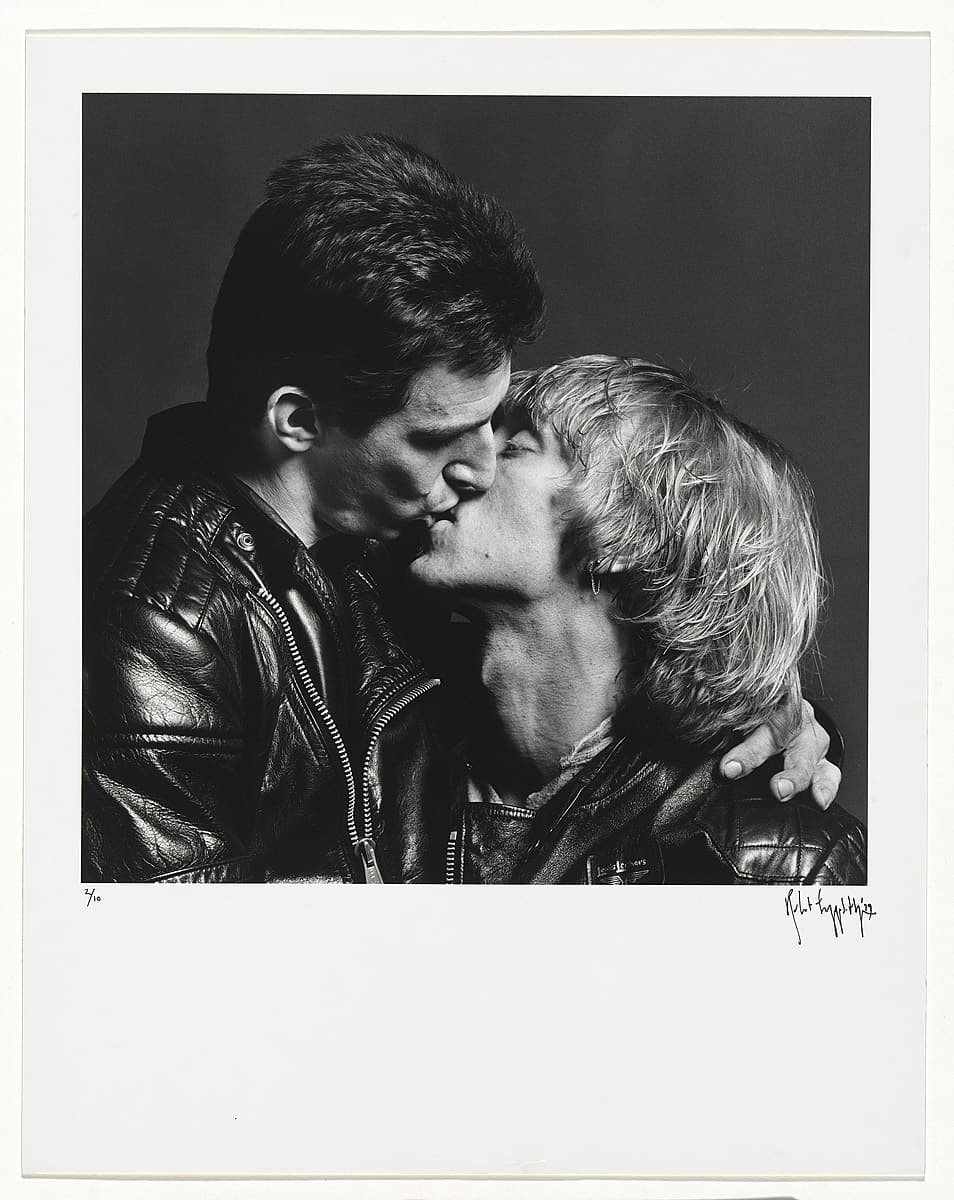

Robert Mapplethorpe

Learn moreLarry and Bobby, NYC 1979

© Robert Mapplethorpe Estate Purchased 1980

More detail | PermalinkDuring the late 1960s, Robert Mapplethorpe made jewellery as well as boxed assemblages and collages that often featured found images, usually pornographic or religious. Around 1971, he started using his own photographs, taken with a Polaroid camera. While he never intended to become a photographer, the medium’s relative immediacy and expediency suited his disposition.[1] His first solo exhibition at New York’s prestigious Light Gallery featured Polaroids of flowers, portraits and erotic scenes. From the start, Mapplethorpe worked across a range of subjects: flower, penis and portrait were considered by him to be, formally at least, ‘the same’, with the same photographic temperament.[2]

Mapplethorpe’s most significant work was made during the 1970s and early 80s, and his photographs engaged a very singular, direct mode with little in the way of secondary or extraneous information. The frontalism, integral to his style, brought together the flatness of his assemblages and Christian icons and the approach of American documentary photography, notably that of Walker Evans. The significance of this work, however, arises not so much from its formalism or classicism, but from the sense of intimacy that is folded into each picture. Mapplethorpe spoke about the photographic moment for him being imbued with the characteristics of a fleeting, intimate encounter, even if before or after the event there was no emotional connection: ‘I think you have to love when you are taking pictures,’ he said.[3]

Larry and Bobby, NYC 1979 is one of many powerful, intimate images of gay lovers embracing, kissing or engaged in sex acts. Although his work was published in gay magazines,[4] from the early 1970s Mapplethorpe generally intended his images for a wide audience, to circulate as ‘contemporary art’.[5] Their importance emerges from their frankness and their representation of gay identity, one that neither relied on nor parodied conventional male/female relations. Their power rests in the apparent trust—and love—that permeates the relationship of photographer, subject and photographic form.[6]

Mapplethorpe’s pictures of intimacy and desire from the 1970s and early 80s serve an important social historical function in the history of gay male sexuality and the way it was represented, recording a relatively short-lived moment of sexual freedom for gay men, one that by the early 1980s was being subject to increased control and regulation following the first reports of men with AIDS.

Shaune Lakin

[1] Robert Mapplethorpe, interview with Janet Kardon, in Janet Kardon (ed), Robert Mapplethorpe: The perfect moment, Institute of Contemporary Art University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1988, p 23.

[2] As above, p 25.

[3] As above, p 26.

[4] Robert Mapplethorpe, cover, Drummer: American review of gay popular culture 24, September 1978.

[5] See Richard Meyer, ‘Imagining sadomasochism: Robert Mapplethorpe and the masquerade of photography’, Qui Parle, 4.1, Fall 1990, esp p 64. For a sense of Mapplethorpe’s performative relationship to ‘wider audiences’, see Dominick Dunne’s terribly homophobic account of the photographer’s final days, ‘Robert Mapplethorpe’s proud finale’, Vanity Fair, February 1989, pp 124–33, 183–7. The gay photographer and contemporary of Mapplethorpe, Hal Fischer—probably anonymously quoted in Dunne’s essay—was highly critical of Mapplethorpe’s ‘commercialism’, and the way he packaged gay male sexuality for the consumption of people ‘on the Upper East Side … [who thought] that they were being really daring’; see his interview with Julia Bryan-Wilson, ‘Gay semiotics revisited’, Aperture 218, Spring 2015, p 39.

[6] ‘It was all about trust’, Mapplethorpe said of sadomasochistic relationships, in a phrase which no doubt speaks of his own relationship to his subjects; quoted in Dunne, p 186.