Arakawa

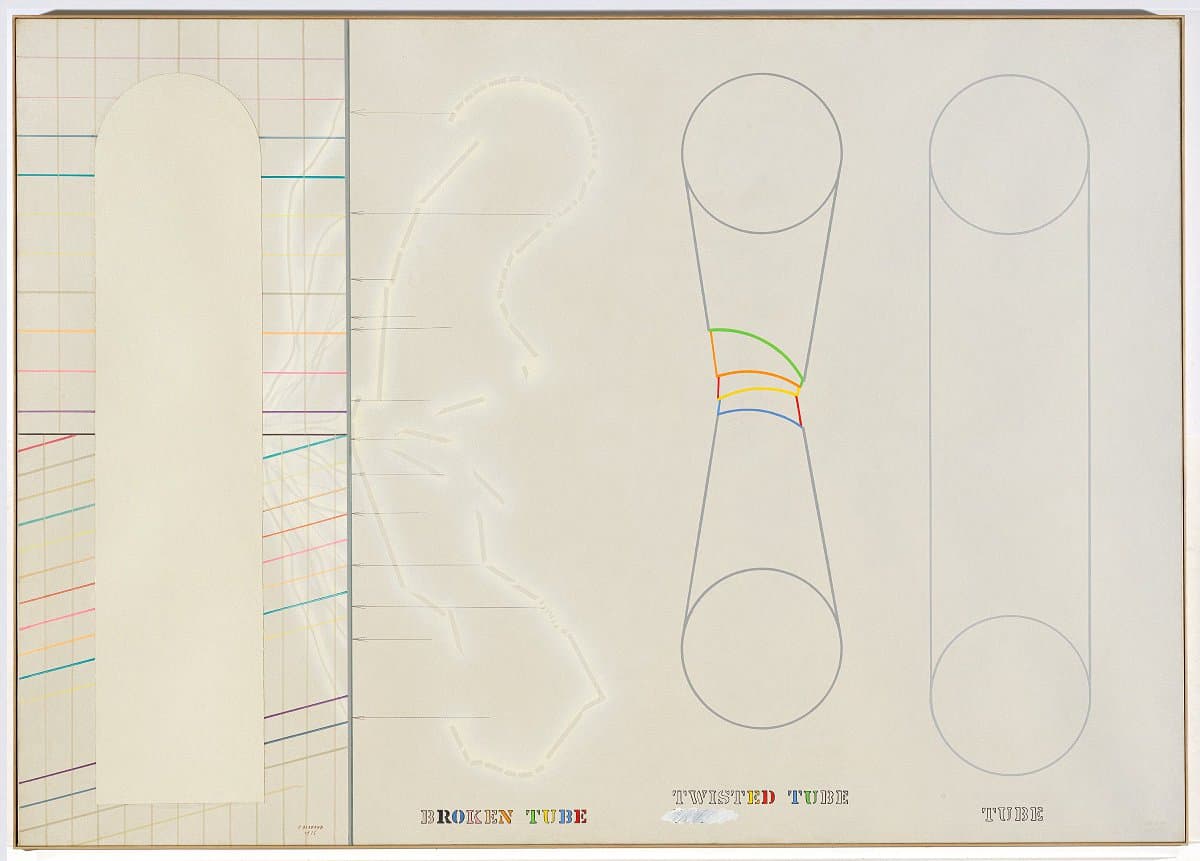

Learn moreTubes 1965

© Estate of Madeline Gins Purchased 1978

More detail | PermalinkArakawa’s early flirtations with angura, or ‘underground’, activities and performances in Tokyo established the foundation for the paintings he made after moving to New York in 1961. His anti-art and antisocial gestures mark a symbolic severance with traditional forms of art and an affirmation of the new. Arakawa’s work incorporates words and schematic images, playing off the ambiguities between verbal and visual languages. His pioneering investigation of language anticipated many of the concerns of Conceptual art in the late 1960s.

Before Arakawa left Japan he completed two diagram‑like works that announced the direction his art was to take in the United States. Describing their origins, he said: ‘Personal things were distressing me. With the diagrams I wanted to map my mental state.’[1] Over the course of the decade this mapping progressed, his work taking on the appearance of visual representations of scientific inquiries, with graphs, charts and diagrams documenting all manner of observation and movement, even including a blueprint for the interaction of ingredients in sweet and sour pork in the print Recipe (Taste it) 1968.[2] The cool and analytical appearance characteristic of Arakawa’s mature work is not surprising given that he studied medicine and mathematics at Tokyo University before making art.

Arakawa continued to identify pictorial equivalents for an idea or ‘mental state’ in the first pieces he made in New York, especially the Bottomless series, begun in 1963. These works typically depicted a square form diminishing in perspective, much like a funnel with an interior mapped by endlessly subdividing grids. According to Madeline Gins, an American poet and Arakawa’s wife, these images represent ‘the thinking field ... which as far as we know ... is itself bottomless ... through which a volume of thought may pass’.[3] The metaphor was extended and refined with the images of diagrammatic tubes that also began to appear in 1963. Tubes 1965 is one of the earlier paintings featuring the motif, which appears in a number of his works of the mid 1960s and again in the 1970s, when it developed further, radiating lines out across the picture plane from a central axis.[4] Broken, twisted or intact, these open‑ended structures were intended ‘as visualisations of thought passages, and as such representations of some behaviour or aspect of the thinking field’.[5]

Tubes was begun in New York in 1964 and completed in 1965. The painting is, however, signed and dated twice—in the lower right as 1965 and as 1975 in the lower left: ‘I was anticipating and incorporating the “Thickness” of a decade,’ explained the artist.[6] In 1978 the painting was damaged in transit, torn in the middle of the blank test‑tube shape on the left. Tubes was returned to Arakawa in New York where he repaired it by collaging onto the damaged area a new piece of canvas in the same test‑tube shape but slightly larger than the original. Arakawa saw this as restoration rather than as a reworking of the painting.

Michael Desmond[7]

[1] Paul Gardner, ‘Arakawa: I am looking for a new definition of perfection’, Artnews, vol 79, no 5, May 1980, pp 60–5.

[2] Silkscreen edition of 60, including one held in the collection of the Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis.

[3] Madeline H Gins, ‘Arakawa’s intention (to point, to pinpoint, to model)’, in Arakawa, Städtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf, 1977, p 14.

[4] Koji Takahashi, ‘Introduction: Forming space’,, in Constructing the perceiver, Arakawa: Experimental works, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 1991, p 306.

[5] Gins, p 14.

[6] Shusaku Arakawa, correspondence of 18 May 1982 with the National Gallery of Australia, NGA file 81/0138.

[7] Adapted and updated from Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond, European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870–1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp 350–2 and Michael Desmond, ‘Arakawa Shusaku’, in Michael Brand (ed), Traditions of Asian Art: traced through the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1995, pp 88, 95, by Bronwyn Campbell.