AES+F

Inverso mundus 2015

Courtesy the artists, MAMM, Anna Schwartz Gallery and Triumph Gallery

Stepping inside the mesmerising 360-degree visual arena that is the seven-channel presentation of AES+F’s Inverso mundus is akin to entering a neo-Baroque fantasy, a colour-saturated construction of contemporary life as medieval carnival. By employing the aesthetic of excess—in the visuals, the sound and vast scale of the work—Inverso mundus stands as a quintessential manifestation of hyperrealism in digital form.

On a forty-minute loop, we witness a parade of perfectly sculpted physiques wearing meticulously selected costumes and performing choreographed sequences individually, in pairs, and in groups. Every projected body, facial expression and physical action is presented in captivating slow motion, imbuing even the most banal gesture with a seemingly monumental meaning. In this way, AES+F’s slick hybrid of composite photography, video and digital technologies presents us with a new type of technical vision, enhanced beyond real life. This is a hypnotic hyperreal vision.

AES+F’s excessive scrutiny of the human form is inspired by classical sculpture. Move beyond the beautifully constructed surface, however, and there lies a darker truth: ‘We feel that contemporary visual culture is very similar to that of the Baroque: everything is extremely expressive, figurative and very visual and founded on images and at the same time very decadent. We try to make it seductive but when you make it too beautiful it begins to be ugly so we are also trying to establish the border between ugliness and beauty’.1

The grand narrative here is forthright: Inverso mundus is the world turned upside-down. Taking inspiration from a sixteenth-century European engraving tradition, AES+F re-present the world as a high-definition blend of reality and artifice, one in which women dominate men, the poor overthrow the rich, children wrest authority from their elders and hybridised animals embark strategically to usurp their human masters.

Jaklyn Babington

1 AES+F, ‘Russian collective AES+F talks to the Art Newspaper about their meteoric success over the last year’, interview by The Art Newspaper, Art Radar, 1 August 2008, artradarjournal.com/2008/08/01/russian-collective-aesf-talk-to-the-art-newspaper-about-their-meteoric-success-over-the-last-year.

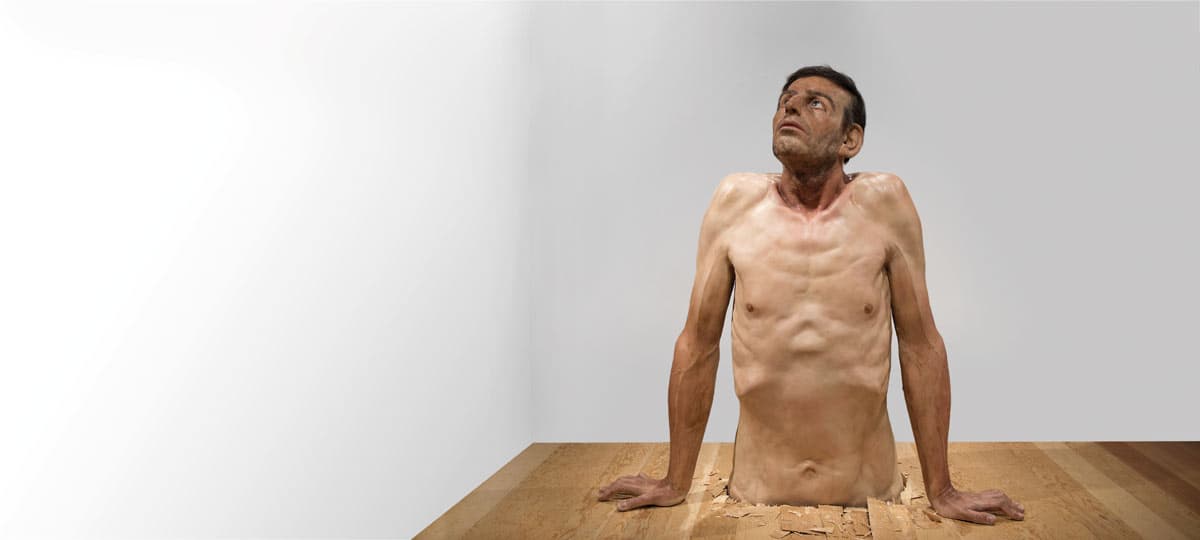

Zharko BASHESKI

Ordinary man 2009-10

Collection of the artist

Zharko Basheski is a Macedonian sculptor who has exhibited in solo and group shows since 1984. Ordinary man was shown along with two other works, each depicting the same ‘ordinary’ man, as part of the project Leap in the Macedonian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2011. The works portray our potential to go beyond ourselves, our limitations and our reality. ‘Sculptures of men as the highest expression of the power of a civilization have always represented gods and heroes,’ writes Emil Aleksiev, ‘but Basheski’s sculptures portray a common everyday man who takes the role of [Friedrich Nietzsche’s] superhuman in his efforts to surpass himself’.1

Cast in fibreglass and containing silicone, pigment, resin and hair, this monumental sculpture dominates space yet spares no detail. The muscles straining throughout the body, veins bulging in the arms and creases of skin all combine to give this work an overwhelming sense of the burden of human endeavour. The pressure on the hands pushing off the floor is clear, fingers are flexed, palms flat and wrists bearing the weight of the effort of pulling oneself out of the ground. The arms are nearly at full extension, with elbows slightly bent, hands turned out and shoulders tensed. From behind, we can see the back muscles ripple and tendons strain due to the effort placed on the body. Through these details, Basheski has represented the strength of will required to rise above ourselves and our circumstances. Yet the figure’s face remains almost serene, with a gaze reaching higher still.

Rebecca Scott

1 Emil Aleksiev, ‘Leap’, trans N Papazovska-Levkova, in Basheski, exhibition book, Bunsen Goetz Galerie, Nurnberg, 2013, p 16, viewed 5 April 2017, bunsengoetz.de/sites/default/files/files/

Baseski_Katalog_2.pdf.

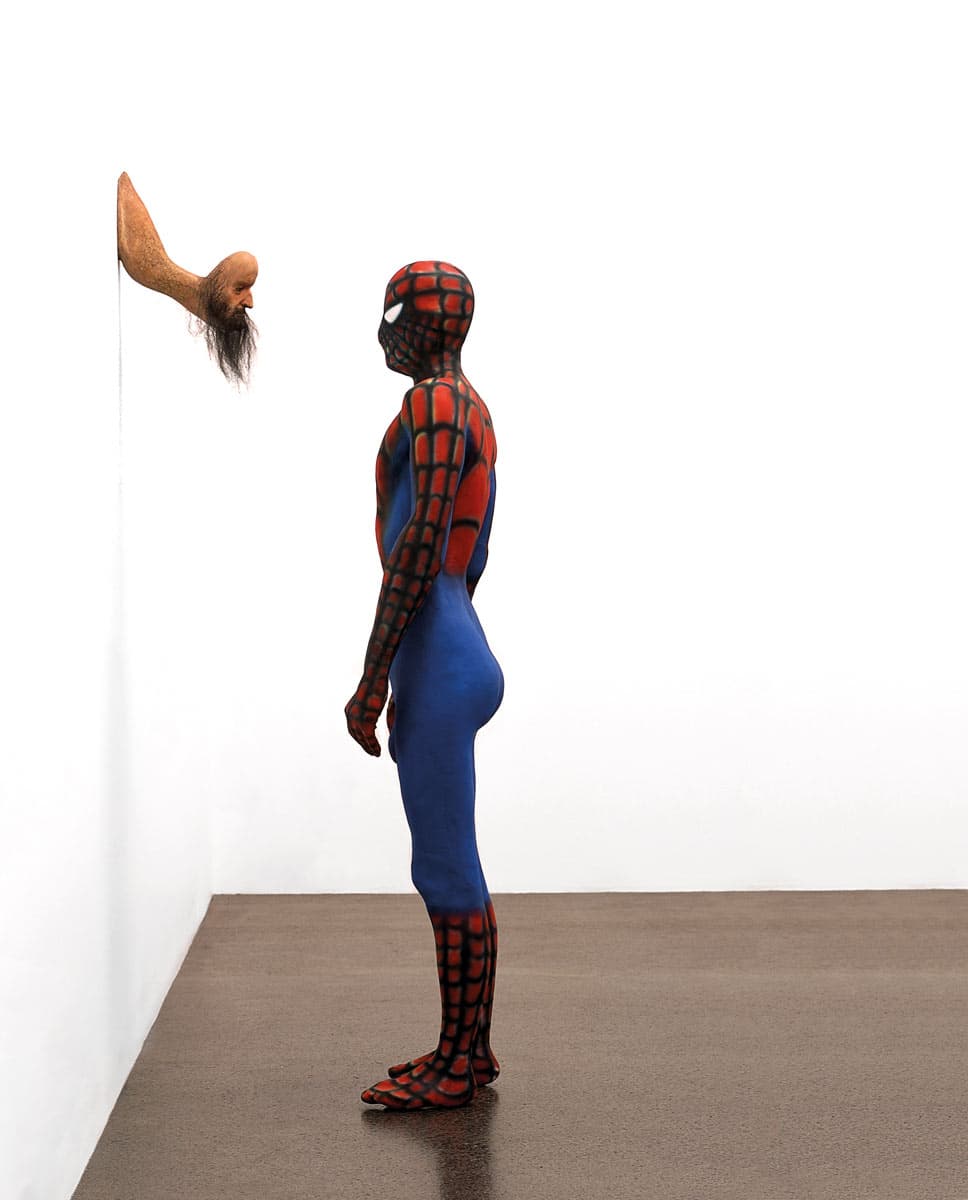

Stephen BIRCH

Untitled 2005

Museum of Contemporary Art, gift of the Estate of Stephen Birch, 2008

Marvel’s Spider-Man is instantly recognisable in Stephen Birch’s uncanny Untitled. But instead of fighting crime, he stands transfixed by a disturbingly malformed, grossly misshapen miniaturised head of a bald, bearded man craning out from the wall on a strangely elongated neck. Staring directly at each other, at eye level, there is an immediate and pervading sense of tension, which seems to dissipate the longer we observe the pair.

Spider-Man initially conjures ideas of power, strength, action, youth, goodness, vitality and, most of all, responsibility. With humour, satire and intelligence, Birch shows a stilted version of our friendly neighbourhood hero, highlighting less of the ‘amazing’ (aside, perhaps, from his impossible bulging crotch) and more of the ordinary, particularly in the figure’s softer and fuller saggy bum. We could be this more humanised hero—the average person dressed up.

Equipped with our knowledge of comic-book heroes, we immediately assume that the figure emerging from the wall is the bad guy, as deformity is so often characteristic of the villain. But, with the emerging figure yet to reveal itself, our unusual hero shows wisdom in his restraint, his impassive stance showing no sign of his famed spider sense. He makes no pre-emptive strike. After all, with great power comes great responsibility.

Instead, an unspoken conversation seems to be occurring, frozen between words. The masked, unreadable expressionless face of Spider-Man potentially reflects the questioning direct gaze of the other being. In an alluring 'Spidey-tingling' way, it makes us slightly uncomfortable, as we perhaps question our own initial reactions to the two protagonists of this hyperreal tableau.

Tina Baum

Maurizio CATTELAN

Ave Maria 2007

Private collection

Maurizio Cattelan often uses humour to examine power relations. His interest in power lies in its ambiguity: in the uncertainty of its points of origin, in the fragile nature of the iconography that serves it and in the ways that it flips between visibility and invisibility. His examination of the iconography of power has often involved the construction of wax effigies, the most notorious of which are La Nono ora 1999, where Pope John Paul II is brought down by a meteorite, and Him 2001, in which a diminutive, supplicant Adolf Hitler prays to God. In both cases, power is undermined by allusions to the fragility and vulnerability of those that possess it.

In Ave Maria, three well-clothed wax-figure arms run along the wall, adopting a pose with a particularly vexed set of associations in the modern history of power. The gesture’s most explicitly contentious connection is with the ‘Roman salute’, a pose commonly (although probably mistakenly) associated with classical Roman soldiers. Of more direct significance to Cattelan’s work, the gesture was adopted by Italian fascists during the 1920s and by the Nazi Party in Germany, usually accompanied with the greeting ‘Heil’. The title of the work, however, invokes the most familiar of Catholic prayers, the Ave Maria (Hail Mary), semantically flipping the experience of the work between an expectation of piety and reverence and the realisation of violence and evil.

Like Him, Ave Maria probes the analogies that run between fascism and Catholicism as sources of repression and sites of power. But Ave Maria invokes a third site of authority and power, the art museum, from whose clean white walls the arms stretch. Just as in the communal experience of a church or fascist rally, the experience of the museum produces abeyance and spectacle. As Cattelan has said of the gesture, ‘The raised arm … is for me an extraordinary symbol of power, an erection in potential but also the absolute suspension of judgment’.1

Shaune Lakin

1 Maurizio Cattelan, interview by Helena Kontova, ‘Maurizio Cattelan: no cakes for special occasions’, trans C Sharp, Flash Art, vol 40, no 257, 2007, p 76.

Berlinde DE BRUYCKERE

Elie 2009

Fundació Sorigué, Lleida, Spain

Duality is perhaps the only singular, permanent aspect of Berlinde De Bruyckere’s practice. Her disturbing, reconfigured bodies oscillate between multiple concurrent and conflicting states, never fully able to settle and rest. Genderless and faceless, these bodies are at once human and monstrous, detached and intimate, religious and secular, dead and dying. De Bruyckere translates the human figure into a metamorphic, fluid entity, but builds up millimetre-thin layers of coloured wax to mimic layers of ectodermal tissue and illustrate blood vessels, veins and contusions.

Her wax figure Elie is a contorted mass of flesh, an artifice constructed using the language of the body. Several casts of various body parts are conjoined here, though they do not reproduce the expected form. The sculpture writhes and torques, grasping desperately at the dirtied pillow beneath it. Hips and shoulders appear dislocated, as if they are sliding and separating from the sunken torso and recessed sternum. The pallid skin is eerily human yet discoloured by shrouds of blue and purple, having reached the point of livor mortis, when blood begins to pool in the lower extremities of the body after death. The finality of death, however, is contradicted by the pose, which suggests an enduring trauma.

Although less explicitly than many of her other sculptures, De Bruyckere’s Elie is bound by religious connotations, specifically the Christian motif of suffering. But philosophical queries into suffering and eventual transcendence are arguably not the focus of her practice. Her work instead most clearly elucidates the artificiality of the image-making process by constructing monstrous but not inhuman forms through the idiom of hyperrealism, a strategy of representation based on exactitude and authenticity.

Bianca Hill

John DEANDREA

Lisa 2016

John DeAndrea & Lorraine DeAndrea

Lisa is presented to the audience in an ambiguous state of repose. Naked and sprawled upon the ground, her languorous body arches slightly upward with the turn in her hips, her limbs falling haphazardly around her. Devoid of context, we begin to wonder what has happened to her. Is she on the verge of sleep or has she collapsed to the ground after reaching sexual climax? Darker allusions also come to mind. Are we perhaps viewing her as she succumbs to death? These questions are not novel. They have plagued representations of the reclining female nude for centuries.

We do not know Lisa, but we have seen her before. Recall, for instance, the titillating Sleeping Venus 1510 of Renaissance master Giorgione or the voluptuous, lethargic female subjects of French Realist Gustave Courbet. With her alabaster skin, hairless body and averted gaze, Lisa could be easily substituted for any of these predecessors. John DeAndrea diligently observes the formula of the reclining nude and, in keeping particularly with the European tradition of art, avoids presenting his figures with a direct gaze. With closed eyes and turned head, Lisa is rendered a passive object to be gazed upon.

Conforming to another well-established trope, she is also depicted without body hair. Hair has long been associated with sexual passion and its absence has been interpreted as denial of sexual power, positioning the audience as the unrivalled voyeur. More contemporary connotations are also unavoidable, with the hairless genital region becoming the erotic ideal in the twenty-first century. DeAndrea’s aesthetic decisions actively encourage our scopophilic gaze, allowing us to look at Lisa as an erotic object and to derive pleasure from this act.

Bianca Hill

John DEANDREA

Ariel I 2011

John DeAndrea

Nubile, slender and inarguably beautiful women presented in varying states of nakedness are the almost exclusive subject of John DeAndrea, and unashamedly so, as that is what he finds most beautiful. By prefacing an utmost concern for beauty, albeit a very personalised interpretation, DeAndrea has entangled himself in one of the most contested spaces in western art history.

Ariel I is an archetype in his oeuvre. She stands absentmindedly, arms raised and hands behind her head as she caresses her long brown hair. Her body language is relaxed and conforms to the concept of contrapposto, a pose originating from classical Greek sculpture where the body’s weight is shifted mostly onto one foot, twisting the shoulders and arms in the opposing direction to the hips and legs. DeAndrea, however, pushes his figure even further by positioning her in the illustrious Praxitelean curve, an exaggeration of contrapposto, which emphasises the sensuous lines of the human form.

A composition of subtle curvatures, Ariel I might be the distant cousin of Praxiteles’s Aphrodite of Cnidus. Although the latter is an aesthetic ideal bereft of human defect and with proportions derived from mathematical ratios, while the former is cast from a live model, with every flaw carefully reproduced in the final painted bronze. DeAndrea’s figure is individualised and imperfect, contrary to the notions of idealism. She is artless, intended instead as a flawless simulacrum of life. Hers is not an artistic beauty but a bodily beauty.

Bianca Hill

Keith EDMIER

Beverly Edmier, 1967 1998

Private collection, the Netherlands

Keith Edmier’s Beverly Edmier, 1967 shows his mother when she was twenty-two years old and pregnant with him. Cast in transparent pink resin, with the foetus visible in utero, the figure is dressed in a facsimile of the pink Chanel suit worn by Jacqueline Kennedy on the day of her husband’s assassination in 1963. This conflation of Edmier’s familial history and the collective cultural memory creates an uncanny effect that is both familiar and grotesque in its distortion of reality.

American popular culture from the 1960s to 1980s, and its real and imagined relationship to the artist, is the pervasive theme that runs through Edmier’s art. Having grown up on the outskirts of Chicago, the shared experience of popular culture by middle-class Americans—who populated new housing developments designed around large, centralised shopping malls with multi-screen cinema complexes, modern churches and new schools—is especially important. The lifestyle of safety and uniformity that the suburbs promoted, however, equally gave rise to a belief that they were unauthentic places of cultural malaise and emptiness.

Hollywood horror and science fiction films, tabloids and newscasts filled with hyperbole all play on our fears. Edmier makes visible this world in which the real and imagined, truth and fiction, become acutely confused, particularly when the influence of time, memory and rumour are introduced: ‘While the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy … concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone … the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) surmised, many years later in 1979, that there may have been a conspiracy’.1

Sally Foster

1 Tom Eccles et al, Keith Edmier 1991–2007, Booth-Clibborn Editions, London, and Centre for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, 2007, p 94.

Cao FEI

Live in RMB City 2009

Courtesy of artist and Vitamin Creative Space M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong, By donation

Cao Fei is a Chinese contemporary artist who has constructed both an avatar, China Tracy, and an extensive work of art, RMB City, using Second Life (SL), an online virtual world developed by the San Francisco-based firm Linden Lab and launched in 2003.

China Tracy appears as a tall, female character with long dark hair—a character physically incongruous to the artist in real life. She wears a silver bodysuit embedded with metallic corsetry, striped leggings and huge silver space boots, a distinctly futuristic fashion aesthetic. In this way, the avatar as a digital self-portrait presents an interesting perspective on self-designed virtual identities. It is fascinating to analyse the way in which residents of SL create their virtual doubles, a construction of identity that goes far beyond the choice of a new name, to the self-styling of a second body and persona. The selection of a new face, hair, clothes, an experimentation with gender, age, nationality and, at extra cost, options to invest in more realistic skin or avatar genitalia (at the ready for any online sexual encounters) all provide the possibility of a complete digital rebirth.

China Tracy exists within the virtual RMB City, a construction of Cao’s fantastic imagining and real-life appropriation: borrowed Chinese motifs and architectural elements include The People’s Palace as the city’s venue for events and celebrations, modelled after the real-world Forbidden City in Beijing, and The People’s Park the equivalent of the Beijing National Stadium (also known as the Bird’s Nest).

As published on the project’s website, ‘RMB City is not a city of magical mirror, it doesn’t restore the full present, nor does it recall our reminiscence of the past. It’s a mirror that partially reflects; we see where we were coming from, discover some of the “connections” that fill the pale zone between the real and the virtual, the clues of which get disturbed, enriched, and polished. New orders are born, so are new, strange wisdom’.

Jaklyn Babington

Cao FEI

RMB City: A Second Life City Planning 2007

M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong, By donation

Cao Fei is a Chinese contemporary artist who has constructed both an avatar, China Tracy, and an extensive work of art, RMB City, using Second Life (SL), an online virtual world developed by the San Francisco-based firm Linden Lab and launched in 2003.

China Tracy appears as a tall, female character with long dark hair—a character physically incongruous to the artist in real life. She wears a silver bodysuit embedded with metallic corsetry, striped leggings and huge silver space boots, a distinctly futuristic fashion aesthetic. In this way, the avatar as a digital self-portrait presents an interesting perspective on self-designed virtual identities. It is fascinating to analyse the way in which residents of SL create their virtual doubles, a construction of identity that goes far beyond the choice of a new name, to the self-styling of a second body and persona. The selection of a new face, hair, clothes, an experimentation with gender, age, nationality and, at extra cost, options to invest in more realistic skin or avatar genitalia (at the ready for any online sexual encounters) all provide the possibility of a complete digital rebirth.

China Tracy exists within the virtual RMB City, a construction of Cao’s fantastic imagining and real-life appropriation: borrowed Chinese motifs and architectural elements include The People’s Palace as the city’s venue for events and celebrations, modelled after the real-world Forbidden City in Beijing, and The People’s Park the equivalent of the Beijing National Stadium (also known as the Bird’s Nest).

As published on the project’s website, ‘RMB City is not a city of magical mirror, it doesn’t restore the full present, nor does it recall our reminiscence of the past. It’s a mirror that partially reflects; we see where we were coming from, discover some of the “connections” that fill the pale zone between the real and the virtual, the clues of which get disturbed, enriched, and polished. New orders are born, so are new, strange wisdom’.

Jaklyn Babington

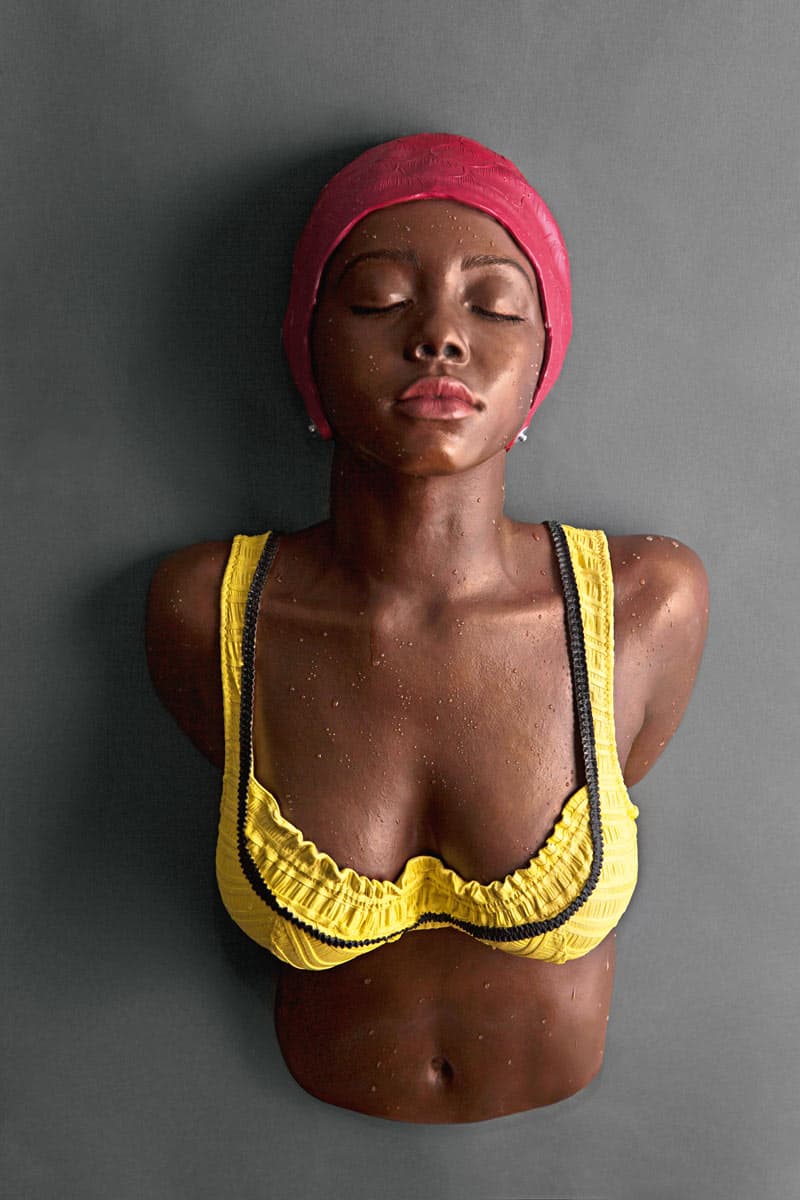

Carole A. FEUERMAN

General's twin 2009-11

Galerie Hübner & Hübner

Carole A Feuerman has worked in the realm of hyperreal sculpture since the 1970s, and with the theme of water since 1958.1 Although her complete oeuvre includes intimate scenes and the occasional man, her main subject has consistently been the female figure, often in the act of bathing or swimming. ‘Swimming and water have fascinated me for as long as I can remember, and as a result, have become the essence of my inspiration for my pieces’, she says.2

General’s twin is one of two nearly identical works. The other is General’s daughter 2011. Both show a young black woman’s torso emerging through a wall, her arms pinned behind her. She is dressed in a playful, frilly bikini with an old-fashioned bathing cap covering her hair. Although the figures are clearly the same woman, there are subtle differences such as the colour of the swimwear and, more importantly, the amount of water on her skin.

Since childhood, Feuerman has been fascinated with the endless patterns that water makes on skin, and this visual idea has progressed into a deeper investigation of its effect on the human psyche. Water, a symbol of life, has a wide range of art historical connotations such as birth, rejuvenation, cleansing and purification. The water beading on Feuerman’s figures imbibes them with both a physical presence and the suggestion of internal happiness. Most of her figures have been conceived with their eyes closed as if in contemplation or reverie. Their graceful upturned faces present proud and confident women who revel in personal triumph and erotic liberation and in the sensual quality of water.

Simeran Maxwell

1 Carole A Feuerman, ‘My subjects are swimmers. My medium is water’, in Swimmers: Carole Feuerman, The Artist Book Foundation, New York, 2014, p 13.

2 Feuerman, p 13.

Daniel FIRMAN

Caroline 2014

Petersen Collection

Caroline is from Daniel Firman’s series Attitude, which began in 2004 and continued until 2016. The original inspiration for the works in the series was the dance technique of contact improvisation in which a dancer defines her relationship to another person or to the space around her based solely on her impulse at the point of contact. Adopting this idea, Firman has created works that seemingly suspend their subjects’ movements at an awkward moment in time, ‘stopped in mid-stream’, as Firman says, ‘trying to lean comfortably against a wall but caught in a position that appears hopeless’.1

Caroline is a resin cast, dressed and accessorised to appear like a woman tangled in her clothes. The sculpture’s unusual situation disrupts the environment and can cause feelings of concern and curiosity. You cannot see her face to read her emotion or gain an understanding of what is happening. Her elbows lean against the wall and her feet are planted solidly on the ground, with one foot turned slightly inward. The view we first see is of a life-size woman with her back toward us, no skin visible, her brown hair shining and her intentions unknown.

Is she taking her jumper off, putting it on or using it to hide her face? These questions and Firman’s ability to suspend movement, time and energy intrigue and engage us instantly in the theatre of human interactions. As part of a twelve-year series, Caroline represents the artist’s intense interest in interrogating not only the body and space but also what unites the two.

Rebecca Scott

1 Daniel Firman, ‘Attitude’, viewed 5 April 2017, danielfirman.com/projects/attitude.

Shaun GLADWELL

Orbital vanitas 2017

Courtesy the artist, Anna Schwartz Gallery and BADFAITH Produced by BADFAITH Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

As part of the Australian artistic collective Bad Faith, Shaun Gladwell is working collaboratively to create virtual-reality works that explore the nexus of art and technologically enhanced human perception. Orbital vanitas is a six-minute muse on humanity’s advancement and an invitation to ponder those bigger questions of life and death.

Putting on a virtual-reality headset and headphones, we are immediately repositioned, transported through our eyes and ears into a hyperreal environment. In the distance, we see an enormous floating human skull approach. It engulfs us, and we move inside its vacant bony chamber, momentarily providing it with the eyes and intellect of a new inhabitant. But this skull is not ours. It is empty and desolate like a barren landscape of cliffs, crevices and caves. ‘Since the beginning of civilization, we have represented the exterior form of our own skulls’, says Gladwell, ‘I wanted to go a step further and enter the interior landscape of the skull. Through virtual reality, the skull transforms into an enormous planet in itself’.1 We exit the skull through the eye socket, and it floats off again, leaving us suspended above the Earth, bodiless, homeless and isolated.

Here, Gladwell makes reference to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, and we can draw parallels with the opening and closing scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s existential 2001: a space odyssey. Orbital vanitas is a reminder of our own flesh-bound mortality, but the virtual-reality experience also prompts a philosophical consideration of contemporary life shaped by recent technological capabilities. It offers us an encounter with the technological sublime.

Jaklyn Babington

1 Shaun Gladwell, ‘Orbital vanitas’, New York Times, 25 January 2017, viewed 7 June 2017, nytimes.com/2017/01/25/opinion/orbital-vanitas.html.

Robert GOBER

Untitled 1992

D.Daskalopoulos Collection

Robert Gober began making strangely realistic wax effigies of men’s legs around 1989. These objects, the first of which was cast from his own leg, reflect the autobiographical nature of much of his work at this time. His mother, a surgical nurse, used to recount to her children one of her first experiences of the operating theatre, which involved having to hold a man’s recently amputated leg.1 The legs thus register a moment of trauma for Gober, referring as they do to an image of his mother that must have been incomprehensible to a young boy.

Gober’s wax legs also embody queer desire, as he has spoken of the erotic appeal of a man’s leg and realised, while making his first leg-effigy, that it was ‘the sight you see if you glance under a stall in a men’s room’.2 In this way, his cast legs refer, in a complex manner, to an unsettling form of realism, one closely, and simultaneously, associated with trauma, phantasy and pleasure.

Fashioned with wax and clothed with a dirty white sock and a well-worn Birkenstock sandal, Untitled also engages with the politics of realism. That is, the realism of the work relates equally to its mimesis—it looks like an actual leg—and to the process of its manual production—in looking at it, we become aware of its intricate and critical handmadeness.

In the 1980s and 1990s, as the logic of late capitalism found its way into the industrial-scale studio practices of many American artists, Gober was still making his work by hand. The work’s handmadeness was intended as a response to the hubris (and masculinity) of industrial-scaled artistic production. There is ‘something inherently suspect in the American imagination if you’re not hiring other people to do the labour for you’, he said at the time, revealing also that the reality-effect of the work, which seems like it should take a long time to produce, is actually ‘a trick. It doesn’t actually take me that long’.3

Shaune Lakin

1 Robert Gober, ‘Success: Robert Gober’, interview with Gary Indiana, Interview, vol 20, no 5, 1990, p 72.

2 Gober, p 72.

3 Robert Gober, ‘Robert Gober: special editions, an interview’, interview by Richard Flood,

The Print Collector’s Newsletter, vol 21, no 1, 1990, p 9.

Duane HANSON

Two workers 1993

© Duane Hanson/VAGA. Licensed by Viscopy, 2017. Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland

Duane Hanson’s work is tinged with feelings of nostalgia and even melancholia. His figures, irrespective of gender or race, appear cut directly from twentieth-century American life. Cast from human models, his sculptures are carefully constructed. Factual accuracy, even banality, is at the heart of his work, centering almost exclusively on lower- and middle-class subjects, ‘… subjects neither picturesque nor grotesque, but uniformly unideal’.1 His figures are never flattered or falsely complimented and are neither cliché nor stereotype. Diner dwellers, suburbanites, blue-collar workers, small-business owners and the like are at the heart of his vision. Two workers epitomises this aesthetic with a pair of construction workers captured mid-job, their tools grasped in their painted bronze fingers.

Hanson deliberately avoids expressive faces and physical interactions between his figures, as he considers these things secondary to the human condition. Instead, his subjects are deeply introspective, absorbed in personal activities and thoughts. This enables the viewer to watch and stare as long as they please, without the feeling of interfering or disturbing the scene. Even in the case of Two workers, the figures appear isolated from one another, wrapped in private contemplation, their eyes downcast and their bearing ever so slightly slumped, as if life has got the better them. They clearly work together, but each is seemingly oblivious of their colleague despite their close proximity.

Simeran Maxwell

1 Kirk Varnedoe, Duane Hanson, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1985, p 11.

Duane HANSON

Woman with a laundry basket 1974

© Duane Hanson/VAGA. Licensed by Viscopy, 2017. South Australian Government Grant 1975 Art Gallery of South Australia

A middle-aged housewife stands absently, a basket of washing propped inelegantly on one hip. Ordinary, inconspicuous, a slice of life of the masses. This was the subjective fodder of Duane Hanson’s work from 1969 onward. Before then, his work addressed harsh and often violent socio-critical themes, his figures abruptly frozen mid-act. When he abandoned this gritty realism to focus on stillness and contemplation, however, his themes also dramatically shifted from politically charged to unremarkable.

A year before he made Woman with a laundry basket 1974, Hanson had moved his family from the heart of the art world in New York to suburbia in Davie, Florida. He said of the decision that New York ‘is more of a synthetic world, this [Davie] is more the real world’.1 It is this realness that he conveys so well in his sculptures and is so perfectly summed up in Woman with a laundry basket. The subjects of his oeuvre present two sides of the same coin, ‘losers in life’ and ‘heroes of the everyday’, and the power of his work comes from the perfect combination of model choice, pose and accessories. In this sculpture, these three factors have been carefully woven together to provoke thoughtful consideration of the mundane and the everyday.

The scene walks a fine line between tragedy and comedy. The woman’s life of drudgery is captured through her haggard appearance. Her blotchy complexion, dimpled knees and ill-chosen attire, however, also combine to create a comical scene, accentuated by the strands of hair escaping from the confines of her rollers and sheer headscarf. The luridly coloured box of Tide laundry powder juxtaposes with her scuffed white clogs, and the hitched-up hem of her ‘flower power’ housedress reveals the red lacy edge of a cheap polyester slip. Even in 1974, her outfit would have appeared past its prime. It is in this meticulously and deliberately chosen ensemble that we find the key to Hanson’s ‘typical American’ creations.

Simeran Maxwell

1 Duane Hanson, quoted in Marco Livingstone, Duane Hanson, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, 1994, p 88.

Sam JINKS

Kneeling woman 2015

Collection of the artist

At first glance, Sam Jinks’s recent work Kneeling woman appears to portray a young woman practising yoga, specifically the child’s pose, or Balasana. Her body faces the floor in a kneeling foetal position, her eyes closed and head balanced above outstretched arms and interlocked hands. Her chest rests on her folded knees and the aura is one of intense, but calm, inward contemplation. Despite its seeming simplicity, Jinks mulled over the composition for years until finally unlocking its purpose after observing a garden orb weaver spider curled up into a protective huddle, its long legs tucked up under its large abdomen.

Kneeling woman is part of a long tradition of realistic sculptural practice in which artists defy the constraints of an inert medium, melding it in ways that breathe life into stasis. Instead of traditional media such as wood, stone or marble, the materials of Jinks’s studio are those of the film-production house where prostheses and bodies are being made. While the Renaissance sculptor represented life convincingly in marble, Jinks’s contemporary silicone bodies trick us into believing they are alive, and not a mere representation. One of the conceits is the rendering of human hair as though it is growing from the head upon which it flows. The kneeling woman has her dark blonde hair casually pulled up in a deconstructed bun, the way young women and teenage girls wear it with studied nonchalance. The errant flyaway strands add to the deception, and the illusion would carry save for the three-quarter scale of the figure. However, this reduction of size and the unheroic aspect of this humble pose take us from gaping at the technical prowess of the sculpture to considering greater themes about intimacy, fragility and the inner life.

Lara Nicholls

Sam JINKS

Woman and child 2010

Collection of the artist

Still and serene, standing like a protectress, an elderly woman holds a naked newborn baby. Draped in a simple floor-length silk nightdress made by the artist’s mother, she nestles the infant into her torso. Her hair is silver-white, creating an impression of a white-on-white composition. She could be the child’s grandmother, or perhaps a symbolic figure sent to watch over this new life.

The baby is entirely naked, too small for his or her skin, which creases beguilingly under the light pressure of the woman’s hands, an action causing the filigree of her veins to slightly bulge. Unlike the woman, the baby’s eyes are alert and open as though he or she is freshly arrived into the world. All the signals and complexity this sculpture holds are rendered in painstaking verisimilitude, as though the translucent skin is real, as though the figure may simply take a step out into the gallery space.

Jinks says of the work, ‘There is something strange with Woman and child because it’s not a common scenario ... It’s so easy to make something that’s recognisable out of that subject, and that’s the knife-edge we all dance on. I almost abandoned that work because of that’.1

Herein lies the paradox of Jinks’s sculptured hyperrealism. The technical virtuosity of the skilful handling of his preferred medium of silicone, delicately tinted, induces the illusion of translucent living flesh. It is a literal sort of medium that tends to bare all, yet Jinks is able to evoke a great sense of ambiguity and mystery. The figures seem like living, breathing human beings from ordinary life, but there is an otherworldliness to them.

Lara Nicholls

1 Sam Jinks, interview with author, 23 June 2017.

Sam JINKS

The deposition 2017

Purchased 2017

The deposition bridges a gap between two important earlier figure groups by Sam Jinks, The pieta 2007 and Woman and child (see page 69). While the arrangement of seated and kneeling familial figures is instantly recognisable throughout the course of art history, this is a modern-day iteration of the biblical story of the Deposition of Christ. Jinks envisaged the composition many years ago and had been wrestling with the narrative intermittently before realising it for this exhibition when commissioned by the National Gallery of Australia. He drew on two key historical sources, the Ancient Roman marble reproduction of Dying Gaul and Raphael’s famous Deposition 1507 and its various preparatory drawings.

While Renaissance depictions often present a dramatic tangle of figures, Jinks has stripped away the interplay and focused on the kernel of the scene: a mother figure comforting a son who is in transition between life, death and the everlasting. The frailty of the male figure and the encroaching age of the elderly mother shroud the scene with a poignant sense of impending grief, as though death has been silenced momentarily before it inevitably intrudes.

The work is highly personal to Jinks, and his own family played a role in the making of it. The hand gesture of the mother figure, as she gently touches the man’s head, holds a great intimacy and is one of the critical elements of the work. He made casts of his grandmother’s hands to capture the maternal intimacy of that gesture. His mother also fastidiously selected the fabric and made the woman’s dress, an integral element of the work.

Jinks captures the quietude and loneliness of dying, evoking a deep sense of intimacy between the two figures. Here an elderly woman comforts a younger man, her son, who has been made frail before his time. While she herself may not be far from death, there is robustness to her nurturing disposition, which questions whether age is the metaphor for death so commonly assumed in popular culture. Despite its everyday quality, The deposition is in essence a romantic work that suggests that the cycles of life have no scripted unfolding and that only love and death endure at the end of all our travails.

Lara Nicholls

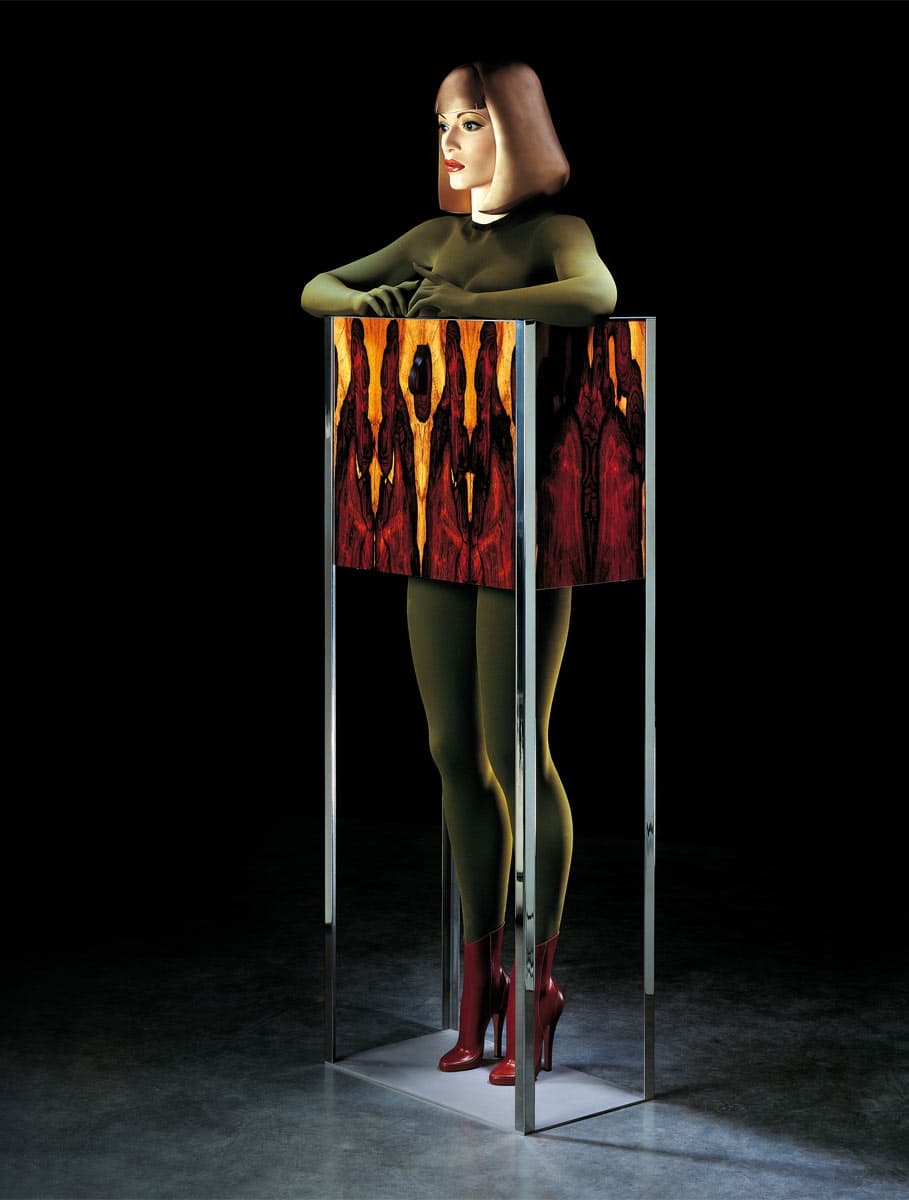

Allen JONES

Refrigerator 2002

Private collection

Allen Jones studied at the Royal College of Arts in London from 1959, when many students were questioning whether compulsory life-classes had become redundant in the era of the newly emerging style of Pop Art. Because Jones refused to take these classes, he was expelled in 1961. He later revisited the controversy with his witty lithographic portfolio Life class 1968. In the manner of a child’s split-page book, it consisted of figure studies, mostly of photographs of a mini-skirted model, with interchangeable upper- and lower-body parts.

Jones continued this imagery of ironic yet dehumanised female figures. His most notable early hyperreal sculptures were in the form of furniture—a chair, table and hatstand—and reminiscent of drawings found in fetish magazines and poster pin-ups, which he collected. The figures were dressed in tight leather costumes manufactured for the artist by the costume designer for the heroine of the 1960s British television series The Avengers. When first exhibited in 1970, these sculptures were considered by feminists to be offensive to women. They were subsequently attacked with stink bombs at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1978, and Chair 1969 was defaced when the group was shown at the Tate in 1986. Jones later noted that they were a commentary and it was unfortunate for him that he had ‘produced the perfect image … to show how women were being objectified’.1

Refrigerator returns to Jones’s idea of fetishistic sculptural furniture. With a helmet of brown hair and an expressionless face, the life-size figure is dressed in a one-piece, figure-hugging costume and stiletto heels worthy of a dominatrix. To emphasise her cold demeanour, and in contrast to her slick appearance, her torso is encased in a beautifully crafted wooden box with a gleaming metal support.

Jane Kinsman

1 Allen Jones, quoted in Martin Gayford, ‘Allen Jones: the day I turned down Stanley Kubrick’, Telegraph, 8 October 2007, viewed 22 March 2017, telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/3668398/Allen-Jones-The-day-I-turned-down-Stanley-Kubrick.html.

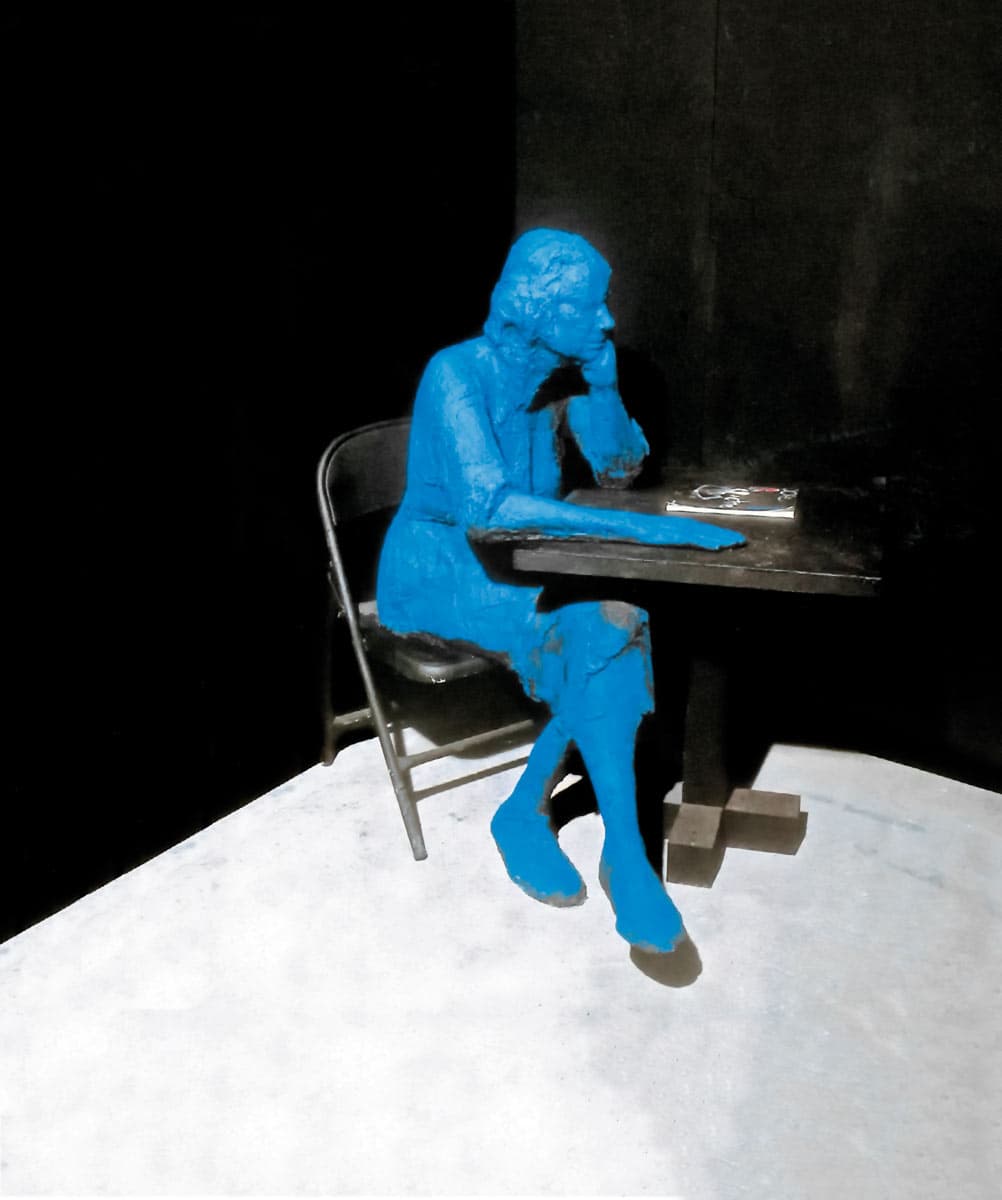

Peter LAND

Back to square one 2015

Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner and Peter Land

A failed attempt. Back to square one. Try again. Repeat.

Endless cycles of falling and failure recur in Peter Land’s work as motifs to explore the difficulties of contemporary existence. Rooted in the deeply personal yet speaking to the universal, his work is driven by an existential line of enquiry: ‘What am I doing here?, Is there a purpose of me being around?, in other words; what’s the value of me as an individual?’1

Back to square one articulates the instability and anxiety that, for Land, are natural by-products of this philosophical interrogation. Greying and dishevelled, a life-size cast of the artist rests in a bed of soiled blankets and cardboard reminiscent of a makeshift homeless shelter, his expression peaceful as he slumbers. Characteristic of his work, the body is elongated, as the head and feet stretch absurdly away from one another, bookending a curving chain of boxes.

While initially conceived in response to the pervasive atmosphere of fear generated by the global financial crisis, Back to square one also gives expression to Land’s personal and artistic misgivings. Homelessness here becomes emblematic of a broader sense of loss, not only physical but also existential, as Land expressed in 1999: ‘My own concern is to try to formulate visually my sensation of not having a stable over-all ideology or religion as the basis of my existence; this feeling of free floating around without the ideological floor, ceiling, or walls to stand on or hold on to’.2

Displayed in an Australian context, this work resonates with current critical issues of homelessness and housing affordability. It serves as a tangible reminder of the precarious reality faced by many and the fallibility of humankind.

Julia Greenstreet

1 Peter Land, ‘A few notes on my work’, in Peter Land, exhibition book, Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit, 2000, p 117.

2 Peter Land, ‘The fall guy’, interview by Michelle Grabner, Cakewalk, no 2, 1999, viewed 24 April 2017, nicolaiwallner.com/texts.php?action=details&id=52.

Tony MATELLI

Josh 2010

Collection of the artist

Tony Matelli’s visually arresting work Josh captures, in freeze frame, the nano-second of a life before it is extinguished. This scene of a shoeless, casually dressed young man suspended just before the point of impact presents a disconcerting yet fragile view of humanity, pushing the limits of our emotions. The anxiety and uncomfortable tension summon unanswerable questions. Did he fall accidentally or was it deliberate? Is he already dead? The suspense of not knowing his predicament is palpable.

That is until we realise, on closer observation, that he is not falling but floating. Perhaps he was never falling, or maybe he was caught by an unseen hand, his trajectory miraculously reversed. Then again, he might be indestructible, frozen in the instant his body lifted once again into the air after impact. Alternatively, he is falling and it is the rest of the world that has been turned on its head. Whatever the case, this uncanny figure defies what we know to be possible. A simple idea made real, Josh transports us to a place where the laws of physics do not apply, radically reorientating our perspective on the world and what we hold to be true and unquestionable.

With this masterfully executed work, Matelli intensifies our sense of horror, sadness, empathy, loss and eventually relief as a means to draw tension into the scene, leaving us, as witnesses, to conjure the circumstances surrounding this single frozen fragment in time and space. There are endless beginnings and endings to this story. But, while not much is given away by the figure, the young man’s seemingly peaceful expression and relaxed body give the impression of someone who has an understanding or acceptance of what is about to transpire.

Tina Baum

Paul MCCARTHY

That Girl (T.G. Awake) 2012-13

D.Daskalopoulos Collection

Paul McCarthy is famed for his disturbing yet unforgettable work. In the 1970s, he donned a woman’s wig and filmed himself cavorting around in a bathtub while eating raw sausage meat until he became violently ill. He then proceeded to slather his genitals in condiments and bathroom products. This form of extreme body art may seem incongruous with That Girl, an installation of three similarly posed life-size nudes of uncanny verisimilitude.

Produced by leading special effects artist Kazuhiro Tsuji and his team, the body casts are of McCarthy’s muse, the actress Elyse Poppers. With slight variations in the placement of limbs and the direction of her gaze, the sculptures’ finely detailed silicone skin reveals Poppers’s every crease, tan line and tiny blemish, yet they also ultimately remain empty. Just like McCarthy’s early video works, That Girl is an exploration of the ‘grotesque body’ as a site of social transgression, a place to question social and cultural standards.

Ideal beauty, according to Johann Joachim Winckelmann, should be devoid of human bodily functions. Orifices, excrescences and bodily fluids should be minimised. The grotesque body contradicts this, exaggerating body parts that either protrude or can be entered. McCarthy constructs his bodies on this premise: ‘I had this thing about exposing the interior of the body, the orifices leading into the body, and what the interior was, and the taboos of the interior’.1

Although Poppers is presented with her legs splayed and her vagina clearly exposed, she is not sexualised or pornographic. Her bodies are opened. While they conform in part to the standards of ideal beauty, they simultaneously transgress its boundaries and interrogate the symbolic significance of the human body today.

Bianca Hill

1 Paul McCarthy, quoted in Jonathan Jones, ‘Paul McCarthy: “I had this thing about exposing the interior of the body”’, The Guardian, 12 November 2011, viewed 16 June 2017, theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/nov/11/paul-mccarthy-artist.

Ron MUECK

Pregnant woman 2002

© Ron Mueck Purchased with the assistance of Tony and Carol Berg 2003

Ron Mueck is at once highly traditional and very contemporary. His methods are those employed throughout history: sketches and maquettes are scaled up with internal armatures to provide support for the final sculpture. His materials, however, are resolutely of the here and now. As Aurélie Verdier points out, Mueck applies his considerable talents and ‘rigorous eye for detail … to engender a personal understanding of the art object’.1

Pregnant woman towers over the viewer. Her firmly planted feet, strong legs, curved spine and large, capable hands held aloft combine to give the overall impression of her body as a load-bearing structure.2 Her mouth is ajar, as if the mere act of breathing is simply too exhausting, and the sheen of perspiration on her forehead attests to her effort. The positioning of her enormous belly at eye-level encourages the viewer’s contemplation. Her closed eyes powerfully convey the inward focus of a mother and intense physicality of pregnancy and of an impending birth.

The inner-life Mueck so convincingly breathes into his sculptures, combined with his extraordinary experiments in scale, ‘promotes an unsettling oscillation between a human subject, a corporeal presence, and a sculptural object’.3 His high-level craftsmanship and attention to universal themes such as birth and death, to portraiture and to examinations of self have brought him worldwide acclaim. He is an artist who effectively captures the effect of time and the signs of wear on the human body. But more than this, his art distils and gives material form to the anxieties of isolation and vulnerabilities that reside deep within us all.

Lucina Ward

1 Aurélie Verdier, ‘Mueck, Ron’, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, viewed 12 April 2017, oxfordartonline.com.

2 Monica Ines Huerta, ‘Encountering mimetic realism: sculptures by Duane Hanson, Robert Gober, and Ron Mueck’, PhD thesis, University of Michigan, 2010, pp 2–3.

3 Justin Paton, ‘Taking the weight’, in David Hurlston (ed), Ron Mueck, exhibition book, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2010, p 55.

Ron MUECK

Old woman in bed 2000-02

Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales - Purchased 2003

Ron Mueck is at once highly traditional and very contemporary. His methods are those employed throughout history: sketches and maquettes are scaled up with internal armatures to provide support for the final sculpture. His materials, however, are resolutely of the here and now. As Aurélie Verdier points out, Mueck applies his considerable talents and ‘rigorous eye for detail … to engender a personal understanding of the art object’.1

The three sculptures in the exhibition demonstrate the range of Mueck’s concerns and his ability to manoeuvre expertly around considerations of size and the complexity of materials. For Old woman in bed, the use of a pedestal (another sculptural tradition) introduces an element of surprise. By encouraging us to approach the work, to peer down at the tiny figure nestled within the fabric, he draws attention to the disjunction of scale between the viewer and subject. Near‑monochrome surrounds, the white linen and ivory blanket all accentuate the pallor of the woman’s skin and her wispy grey hair, lined face and white eyelashes. Here is someone who seems to hover on the brink of life and death. Her diminutive nature emphasises the idea that she is fading from the world. We might almost imagine that we hear the woman’s breath rattling her shrunken frame.

The inner-life Mueck so convincingly breathes into his sculptures, combined with his extraordinary experiments in scale, ‘promotes an unsettling oscillation between a human subject, a corporeal presence, and a sculptural object’.2 His high-level craftsmanship and attention to universal themes such as birth and death, to portraiture and to examinations of self have brought him worldwide acclaim. He is an artist who effectively captures the effect of time and the signs of wear on the human body. But more than this, his art distils and gives material form to the anxieties of isolation and vulnerabilities that reside deep within us all.

Lucina Ward

1 Aurélie Verdier, ‘Mueck, Ron’, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, viewed 12 April 2017, oxfordartonline.com.

2 Justin Paton, ‘Taking the weight’, in David Hurlston (ed), Ron Mueck, exhibition book, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2010, p 55.

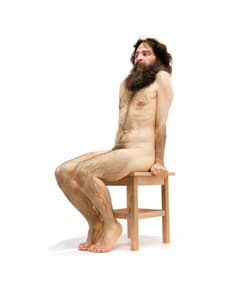

Ron MUECK

Wild man 2005

Photographer: Mark Ashkanasy, © Ron Mueck Collection of McClelland Sculpture Park + Gallery

Ron Mueck is at once highly traditional and very contemporary. His methods are those employed throughout history: sketches and maquettes are scaled up with internal armatures to provide support for the final sculpture. His materials, however, are resolutely of the here and now. As Aurélie Verdier points out, Mueck applies his considerable talents and ‘rigorous eye for detail … to engender a personal understanding of the art object’.1

The gigantic Wild man is animated and firmly rooted to his spot. His back muscles emphasise the torsion of his body as he perches on the edge of the stool, the curve of his thigh muscles highlighted by the geometry of the furniture. The minutiae of the finish are compelling: the strands of dark hair on his shaggy head and his mane-like beard, torso, arms and legs. The ‘wild man’ of the title refers to an individual outside of society, but Mueck’s figure looks more terrified than terrifying. His toes are clenched and white-knuckled, and he leans away as if to avoid our threatening presence.

The inner-life Mueck so convincingly breathes into his sculptures, combined with his extraordinary experiments in scale, ‘promotes an unsettling oscillation between a human subject, a corporeal presence, and a sculptural object’.2 His high-level craftsmanship and attention to universal themes such as birth and death, to portraiture and to examinations of self have brought him worldwide acclaim. He is an artist who effectively captures the effect of time and the signs of wear on the human body. But more than this, his art distils and gives material form to the anxieties of isolation and vulnerabilities that reside deep within us all.

Lucina Ward

1 Aurélie Verdier, ‘Mueck, Ron’, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, viewed 12 April 2017, oxfordartonline.com.

2 Justin Paton, ‘Taking the weight’, in David Hurlston (ed), Ron Mueck, exhibition book, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2010, p 55.

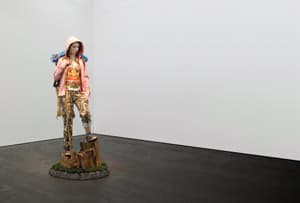

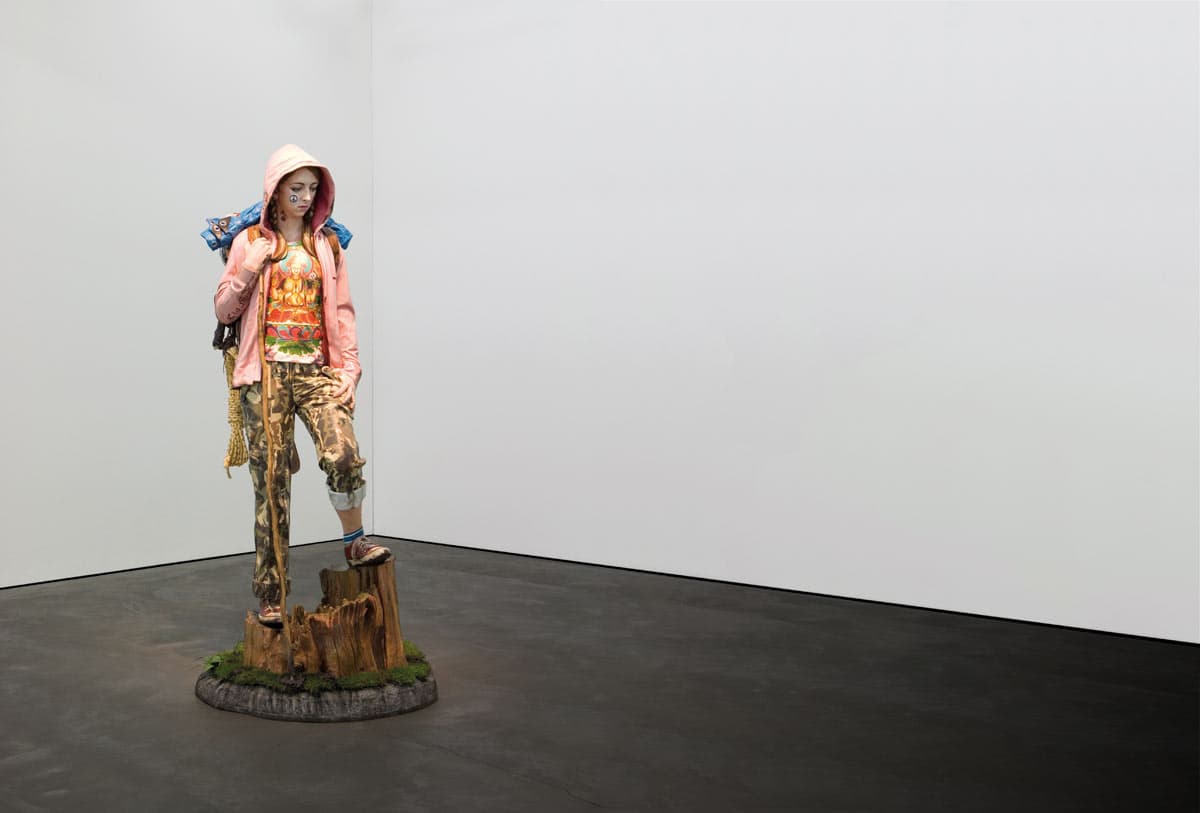

Jan NELSON

Strange days 2013

© Jan Nelson. Licensed by Viscopy Museum of Contemporary Art, donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program by the artist, 2015

From the shadowed folds of her pastel pink hoodie, a young woman avoids our gaze. Balancing in sneakers on an uneven tree stump, she surveys the ground immediately ahead. Thwarted, we rely on forming an impression through body language and clothing. Her piercings and the peace sign drawn on her right cheek suggest an interest in alternative subcultures, while her outfit is an eclectic mix of a new-age printed tee-shirt and camo-patterned trousers.

Her slight frame shoulders a leather backpack with a rolled-up tarp and a dangling hank of climbing rope, while her right hand leans on a thin, whittled walking stick. The girl seems prepared for the journey ahead, yet her apparent age suggests that she is entering into the complicated terrain of adolescence from which she will emerge into the adult world where democratic idealism meets gritty reality.

The title of Jan Nelson’s Strange days references a track by American rock band The Doors, whose darkly jangling poetry provided a soundtrack for the countercultural resistance of the late 1960s and 1970s. The figure is based on a young woman Nelson glimpsed at a political rally organised by the recent Occupy movement protesting against social and economic inequality. This sculpture reflects the artist’s ongoing interest in the shifting relationship between vulnerability and defiance, which she has also explored through hyperreal paintings and photographs of teenagers.

Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax

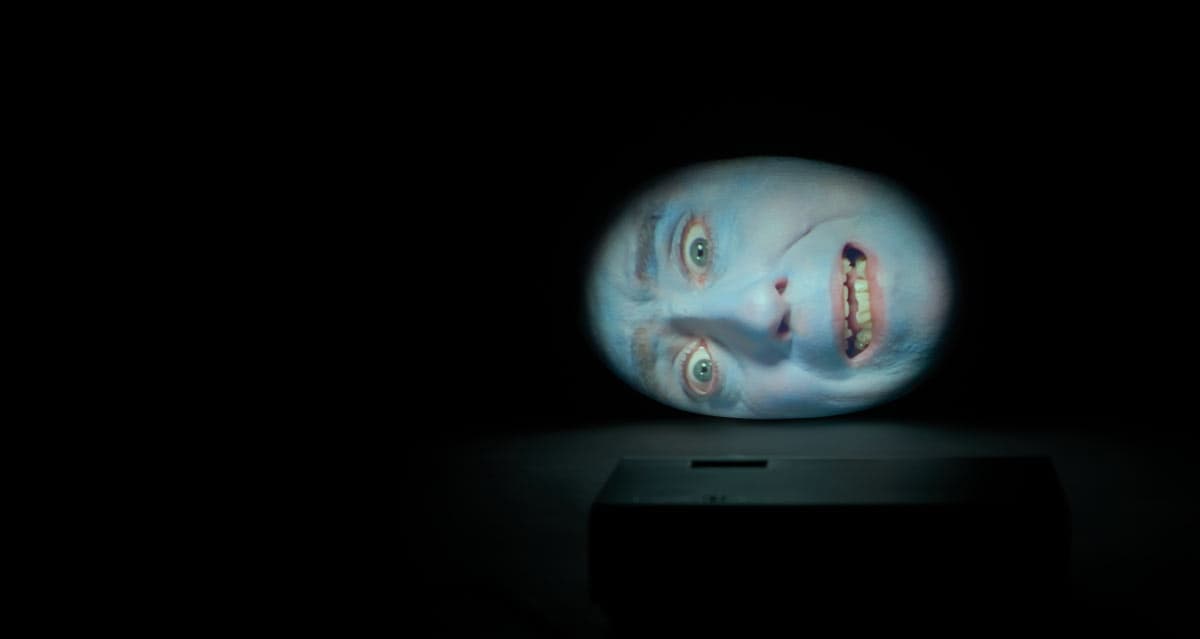

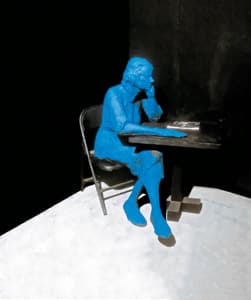

Tony OURSLER

Incubator 2003 2003

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures Gallery Purchased 2003

Disembodied, alone and utterly pathetic, Tony Oursler’s pallid face lies on the floor, projected onto an ovular form cast in fibreglass. ‘I see you, you see me; I see you, you see me’, bleats the artist. ‘I die. Oh I die … keep me alive with your eyes’, he snivels, becoming more anxious and demanding. ‘Ouch! Don’t look away; don’t look away, don’t look away; please look at me. Attention! Attention!’, he pleads pitifully, begging the audience not to abandon him in the darkness.

While this object may assume Oursler’s likeness, it is not a self-portrait. These demands are not his own. They represent the collective voice of our society, consumed by the media and its constitutive gaze. The media’s ability to produce entirely constructed simulacra—copies without any original referent—was central to cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard and his articulation of hyperreality. This capacity has been an enduring anxiety for Oursler. He has said, ‘My main focus is the position of the individual in relation to the mass of information we are fed and the manipulation we undergo by the powers that be …’1

Incubator is a visual and auditory manifestation of the ‘social’ interactions which occur within the digital landscape. Created in 2003, a year prior to the release of the ubiquitous social-media platform Facebook, Oursler prefigures the unsettling way we can become defined by our virtual existence, in which our actuality is just one of innumerable copies, or reductions, of ourselves—a profile picture, a status update, a hashtag.

Bianca Hill

1 Tony Oursler, quoted in Deborah Rothschild, ‘Introjection: in Oursler’s world, no one escapes its unbidden influences’, in Introjection: Tony Oursler, mid-career survey, 1976–1999, Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, 1999, p 12.

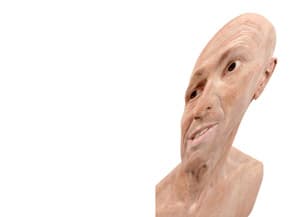

Evan PENNY

Panagiota: conversation #1, variation 2 2008

Courtesy of the artist

‘I never really thought of myself as a realist’ is a surprising statement for Evan Penny to make given that he creates lifelike sculptures, that is, sculptures that inevitably claim to be authentic representations of the world due to the precise exactitude of their surfaces.1 His interest is in the problematics of representation, and his field of enquiry is invariably the area between two-dimensional visual media and three-dimensional sculptural form. How does our sophisticated ability to read each other and ourselves in an image, particularly a photographic image, interact with the way we encounter each other and ourselves in real time and space?

Penny created visual effects in the film industry for thirteen years, placing him ‘inside the machinery of popular culture’.2 As an artist, however, he interrogates the unreliability of the records of our lives upon which we build a picture of our past. Our imaginations, he posits, are informed, and limited, by the particularities of the technology we have available to us. We have become so accustomed to the visual tricks that are employed to manipulate two-dimensional images that we are no longer aware of them. By inverting the process and rendering these images once again three-dimensional, as sculptures, Penny exposes the illusion and the deformity of the human image in the media age.

The source images he used to create his Panagiota works were taken during a conversation with his friend and fellow artist Panagiota Dimos, whose distorted face we see—the distortion produced by spooling film through a camera over a thirty-second period while the aperture remained open. The features are elongated, unreadable, transformed into a flow of colour and line in time and space. An experience Penny then characteristically meticulously sculpts into solid matter.

Anne O’Hehir

1 Evan Penny, ‘Seeing ourselves now’, interview by David Moos, in DJ Schreiber (ed), Evan Penny: Re Figured, exhibition book, Walther König, Cologne, 2011, p 23.

2 Penny, p 23.

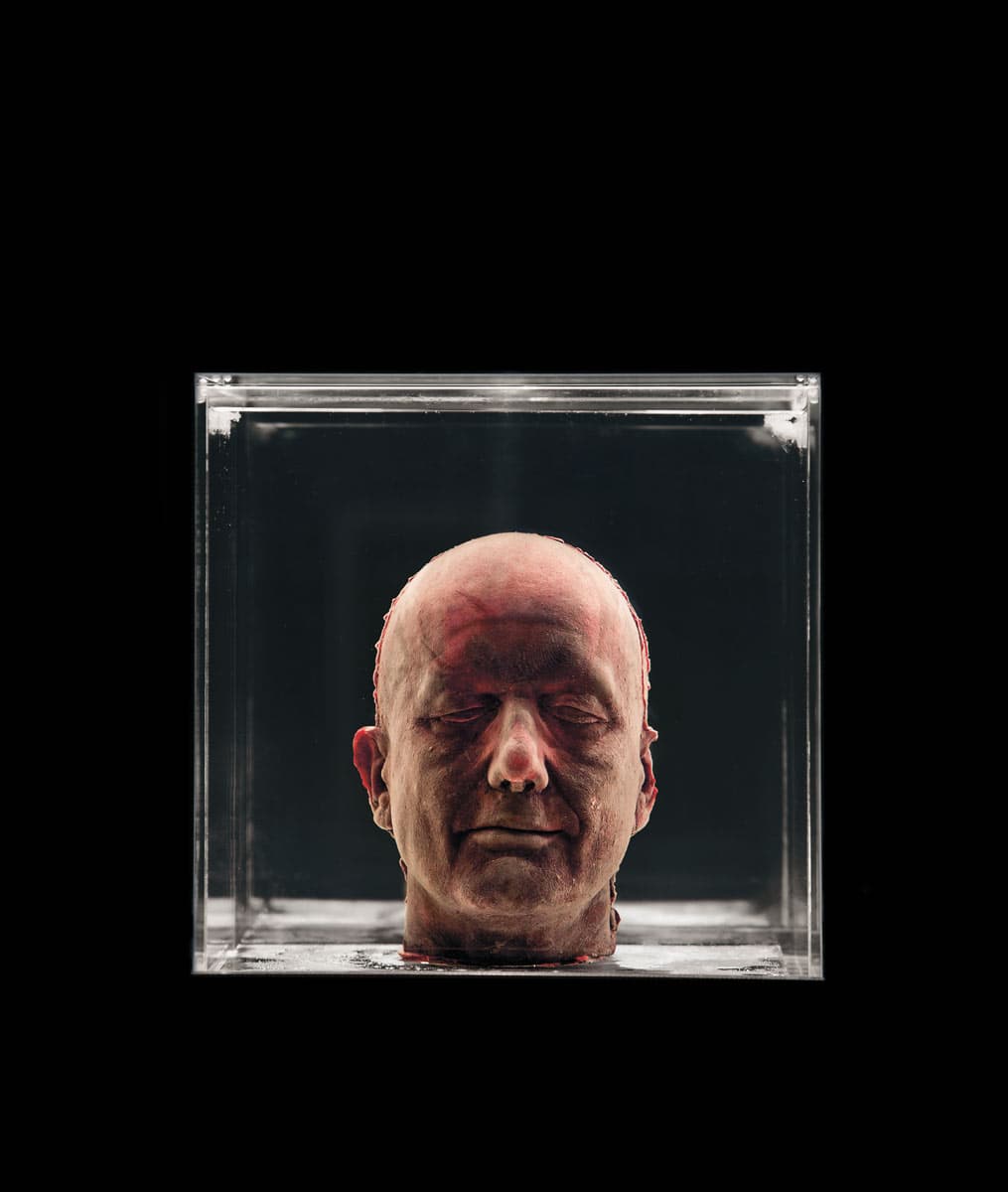

Evan PENNY

Self stretch 2012

Courtesy of the artist

Penny used to work by moulding silicone forms from sculpted clay originals. In recent years, however, he has turned to new technologies to develop his process and enhance his investigation of the problematics of representation in the media age. His starting point is now often a three-dimensional digital scan of a body, or part thereof, which is then manipulated by computer software and carved out of foam by an automated milling machine to produce the basic shape. He then refines and reworks his figures with clay. Even his smaller sculptures can take two to three hundred hours to complete. His practice remains staunchly craft-based and careful observation is a basic tenet. While scanning accurately records the overall shape of the figure, the clay modelling process, with its accumulation of many elements over time, is what animates the final sculpture.

In his stretch projects, which he began in 2003, he has dramatically changed the shape of the body while unnervingly maintaining a proportional equivalence to the original form. His use of three-dimensional scanning and photography and image-editing programs has opened up countless possibilities for him to mess with our assumptions of a fixed and stable world. As David Moos expressed when interviewing the artist in 2011, we sense an image but see an object.1 By distorting the human figure in ways that belong to two-dimensional image manipulation and then presenting the result three-dimensionally in sculptural form, Penny makes work that is simultaneously impossible yet irrefutable.

Anne O’Hehir

1 ‘Seeing ourselves now’, interview with Evan Penny, in DJ Schreiber (ed), Evan Penny: Re Figured, exhibition book, Walther König, Cologne, 2011, p 20.

Patricia PICCININI

Bootflower 2015

Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco Collection of Detached Cultural Organisation, Hobart

While Patricia Piccinini engages with certain aspects of scientific advancement, it is the idea of our ‘technoculture’—our contemporary culture as continuously adapting to, and being transformed by, science and technology—that lies at the core of her practice. Specifically, she is concerned with how technocultural advances register themselves on our collective emotional and ethical consciousness. She uses the hyperreal genre as a catalyst to unsettle our acceptance of culturally prescribed identities, positing a ‘new natural’ in light of recent scientific and technological modifications of the human form and human life.

As one of the most fascinating displays in Hyper Real, Piccinini presents two of her works. Bootflower, a limbless, flesh-bound torso—a fantastical hybrid creature of human, animal, plant and consumer-product characteristics—sits within Meadow, a field of genetically identical flowers and the result of the plant’s asexual reproduction abilities to clone itself. As Piccinini says, ‘Bootflower represents a very contemporary way of seeing the body, as amorphous and protean and infinitely malleable. This is a body that can be endlessly redefined according to our desires. However, it is also self-sustaining and fertile, as evidenced by the eggs, and, in that way, the antithesis of the sterility of corporate GMOs’.1

On our approach, the fantastical creature turns its neck and head—a cowboy boot that has peeled open like the petals of a flower to reveal a pistil covered in human-like skin, complete with fine, downy hairs. We have interrupted this creature in the process of laying its eggs and are stunned. Here is a body we have never seen before, perhaps never imagined possible, and we are interlopers on an unnatural yet wholly natural scene. Our encounter with this transgenic organism is dramatically enhanced by the use of a mirrored environment, a staging device, that produces the effect of standing within an infinite field of posthuman replication.

Jaklyn Babington

1 Patricia Piccinini, correspondence with Jaklyn Babington, 11 July 2017.

Patricia PICCININI

Meadow 2017

Collection of the artist

While Patricia Piccinini engages with certain aspects of scientific advancement, it is the idea of our ‘technoculture’—our contemporary culture as continuously adapting to, and being transformed by, science and technology—that lies at the core of her practice. Specifically, she is concerned with how technocultural advances register themselves on our collective emotional and ethical consciousness. She uses the hyperreal genre as a catalyst to unsettle our acceptance of culturally prescribed identities, positing a ‘new natural’ in light of recent scientific and technological modifications of the human form and human life.

As one of the most fascinating displays in Hyper Real, Piccinini presents two of her works. Bootflower, a limbless, flesh-bound torso—a fantastical hybrid creature of human, animal, plant and consumer-product characteristics—sits within Meadow, a field of genetically identical flowers and the result of the plant’s asexual reproduction abilities to clone itself. As Piccinini says, ‘Bootflower represents a very contemporary way of seeing the body, as amorphous and protean and infinitely malleable. This is a body that can be endlessly redefined according to our desires. However, it is also self-sustaining and fertile, as evidenced by the eggs, and, in that way, the antithesis of the sterility of corporate GMOs’.1

On our approach, the fantastical creature turns its neck and head—a cowboy boot that has peeled open like the petals of a flower to reveal a pistil covered in human-like skin, complete with fine, downy hairs. We have interrupted this creature in the process of laying its eggs and are stunned. Here is a body we have never seen before, perhaps never imagined possible, and we are interlopers on an unnatural yet wholly natural scene. Our encounter with this transgenic organism is dramatically enhanced by the use of a mirrored environment, a staging device, that produces the effect of standing within an infinite field of posthuman replication.

Jaklyn Babington

1 Patricia Piccinini, correspondence with Jaklyn Babington, 11 July 2017.

Patricia PICCININI

The long awaited 2008

Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco Collection of Detached Cultural Organisation, Hobart

Empathy for the outsider and the outcast is at the heart of Patricia Piccinini’s art. The surreal and uncanny are also integral to her practice. Across diverse media, she creates worlds in which the imagination and advances in genetic engineering come together and jostle for space. At times, in her hybrid sculptures, she recreates, merges and mutates forms into new realities, akin to the ‘monster’ of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. How we perceive such creations is cause for reflection, taking us into landscapes of heart and mind. They can be considered as meditations on beauty and ugliness and on our conditioned responses to these phenomena in a real and hyperreal world.

We find ourselves in a twenty-first century world shaped by advertising and digitally enhanced media in which notions of beauty are generally one-dimensional. In Piccinini’s The long awaited, a large mammalian woman inspired by a dugong is a grandmother-mermaid like no other. Lying on a bench, she allows herself to be comforted by a young boy. Eyes closed, they represent a state of unaffected tenderness. ‘I am interested in the relationships between generations’, says Piccinini.‘1 It is important to me that she is a grandmother figure…the dynamic is that the boy is comforting her. Usually it is the other way, but I think that her acceptance of his nurturing is an incredible display of inner strength. I feel it is much easier to nurture someone else than to allow them to nurture you.’

Piccinini finds the natural world a great teacher. She often undertakes research into creatures of the wild such as dugongs. For her, the dugong is mysterious. ‘Of course, they are often cited as the inspiration for the stories of mermaids, and, in real life, they are the only herbivorous aquatic mammal, the cows of the sea. They’re very placid and nurturing. They keep their children on their backs for two years to help them to breathe, and I find the image of that quite moving.’

Like the Surrealists before her, Piccinini taps into imaginary aspects of the subconscious and dreams that are timeless, merging them with the extraordinary nature of the real world as well as ideas around biotechnological developments. She pays attention to intersections between the real and the artificial and, in the process, asks probing questions around human behaviour and the brave new world in which we find ourselves. What happens when we are faced with new and unexpected realities? Can we break down barriers of conventional perception? Piccinini poses these questions and invites an empathic response. She does not, however, provide easy answers but opens up a vast field of enigma reverberating into the future.

Deborah Hart

1 All quotes Patricia Piccinini, interview with author, 12 May 2017.

Patricia PICCININI

The breathing room 2000

Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco Collection of the artist

A close encounter with a strange hybridised body, Patricia Piccinini’s The Breathing Room is an installation of computer-generated animation. Through zoomed-in and inverted folds, nipples, moles, hair and orifices, we are surrounded by skin, moving, sliding, rubbing, slipping. We are disoriented, unable to determine if we are on the inside or outside of the body. Piccinini positions us within an intimate space that soon becomes claustrophobic and transitions into a panic-inducing space. We realise that this simulated body is not as it should be and wonder if it is a human body at all. We hear its breathing growing steadily in sexual excitement, or is it a laboured struggle for life? Immersed in the sound of another’s breath, we lose track of our own.

In her ‘A cyborg manifesto’, writer Donna Haraway explains, ‘A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction’.1 It is precisely this kind of organism with whom we come into close contact in The Breathing Room. Piccinini forces us into a spatial and audial conjoining of bodies—a human body with that of a cyborg, real life immersed within a simulation of it. This is a world in which the categories of ‘real’ and ‘natural’ are no longer finite. In this way, Piccinini’s work is simultaneously terrifying and strangely life-affirming.

We come into this world as beings totally dependent on the physical nurturing of another, and grow, gradually separating ourselves from our mother’s body. Following birth, never again do we experience a physical dependency so great or with such corporeal connectedness. It is this concept of inter-dependency, of a nurturing enacted through the physical body, that resurfaces as a major theme throughout Piccinini’s work. Above all else, she urges us to extend the love and care we have for each other to variant life forms, even those that appear as extreme manifestations of the scientifically mutated, artificially modified or technologically adjusted human form.

Jaklyn Babington

1 Donna Haraway, ‘A cyborg manifesto: science, technology and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century’, in David Bell and Barbara M Kennedy (ed), The cybercultures reader, Routledge, London and New York, 2000, p 291.

Patricia PICCININI

The welcome guest 2011

Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco Collection of the artist

Empathy for the outsider and the outcast is at the heart of Patricia Piccinini’s art. The surreal and uncanny are also integral to her practice. Across diverse media, she creates worlds in which the imagination and advances in genetic engineering come together and jostle for space. At times, in her hybrid sculptures, she recreates, merges and mutates forms into new realities, akin to the ‘monster’ of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. How we perceive such creations is cause for reflection, taking us into landscapes of heart and mind. They can be considered as meditations on beauty and ugliness and on our conditioned responses to these phenomena in a real and hyperreal world.

An emotional connection is apparent in The welcome guest in which a young girl standing on a bed is approached by a sloth-like creature reaching out in an embrace. While adults might be filled with anxiety at the sight of such a creature approaching the child, Piccinini remarks that children are more open to ideas of difference. In a child’s world, imagination and reality are not separate but intertwined—and, in this instance, the girl is enchanted. The title derives from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s often quoted, ‘Beauty is everywhere a welcome guest’. Piccinini wanted to consider notions of beauty and otherness in relation to genetic engineering and reinventing realities.

‘So we have the peacock, an animal that has evolved to be visually extraordinary. His feathers have no other use beyond being beautiful to a female. Yet, when we think of artificial evolution, we think only in terms of utility’, says Piccinini. ‘On the bed, there is this creature that’s based on a sloth, with these ridiculous claws and amazing hair patternation, neither of which are useful. Yet the little girl finds it wonderful. Is that enough? … Why is it okay to change nature for the sake of human utility but not for beauty?’

Like the Surrealists before her, Piccinini taps into imaginary aspects of the subconscious and dreams that are timeless, merging them with the extraordinary nature of the real world as well as ideas around biotechnological developments. She pays attention to intersections between the real and the artificial and, in the process, asks probing questions around human behaviour and the brave new world in which we find ourselves. What happens when we are faced with new and unexpected realities? Can we break down barriers of conventional perception? Piccinini poses these questions and invites an empathic response. She does not, however, provide easy answers but opens up a vast field of enigma reverberating into the future.

Deborah Hart

1 All quotes Patricia Piccinini, interview with author, 12 May 2017.

Patricia PICCININI

Eulogy 2011

© Patricia Piccinini Warwick and Jane Flecknoe Bequest Fund 2015

Empathy for the outsider and the outcast is at the heart of Patricia Piccinini’s art. The surreal and uncanny are also integral to her practice. Across diverse media, she creates worlds in which the imagination and advances in genetic engineering come together and jostle for space. At times, in her hybrid sculptures, she recreates, merges and mutates forms into new realities, akin to the ‘monster’ of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. How we perceive such creations is cause for reflection, taking us into landscapes of heart and mind. They can be considered as meditations on beauty and ugliness and on our conditioned responses to these phenomena in a real and hyperreal world.

Eulogy is an example of the adage that truth is stranger than fiction. Although Patricia Piccinini often imagines new possibilities in her works, she remarks upon how her own inventions are often quite tame compared with bizarre creatures that actually do exist, the blobfish being one such ‘miraculous aquatic creature’.

Relatively unknown to science until deep-sea fishing boats started pulling them up in the 1980s, the blobfish has been driven to the brink of extinction, ‘victims of collateral damage’. Attitudes are, however, shaped by its appearance. As Piccinini says: ‘I find it hard to imagine a “Save the Blobfish” campaign … It is certainly no panda or mountain gorilla. However, despite all that, to me the blobfish is extraordinary … This sculpture is a celebration of the simple, gormless, wonderful existence of the blobfish. It is a eulogy for this particular specimen, supported in death by a very ordinary-looking man’.

Patricia Piccinini challenges preconceived ideas of what constitutes beauty, exposing emotional weaknesses in human character when it comes to ideas around the boundaries between the acceptable and the unacceptable, the endearing and the grotesque.

Like the Surrealists before her, Piccinini taps into imaginary aspects of the subconscious and dreams that are timeless, merging them with the extraordinary nature of the real world as well as ideas around biotechnological developments. She pays attention to intersections between the real and the artificial and, in the process, asks probing questions around human behaviour and the brave new world in which we find ourselves. What happens when we are faced with new and unexpected realities? Can we break down barriers of conventional perception? Piccinini poses these questions and invites an empathic response. She does not, however, provide easy answers but opens up a vast field of enigma reverberating into the future.

Deborah Hart

1 All quotes Patricia Piccinini, interview with author, 12 May 2017.

Patricia PICCININI

Prone 2011

Collection of the artist

Empathy for the outsider and the outcast is at the heart of Patricia Piccinini’s art. The surreal and uncanny are also integral to her practice. Across diverse media, she creates worlds in which the imagination and advances in genetic engineering come together and jostle for space. At times, in her hybrid sculptures, she recreates, merges and mutates forms into new realities, akin to the ‘monster’ of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. How we perceive such creations is cause for reflection, taking us into landscapes of heart and mind. They can be considered as meditations on beauty and ugliness and on our conditioned responses to these phenomena in a real and hyperreal world.

Patricia Piccinini challenges preconceived ideas of what constitutes beauty, exposing emotional weaknesses in human character when it comes to ideas around the boundaries between the acceptable and the unacceptable, the endearing and the grotesque. New life suggests possibility and hope.

Yet when the perfectly formed body of a small baby has a face that appears deformed, or reformed, as in Prone, mirroring a bat’s facial structure (encompassing its remarkable feature of echolocation), there is a push-pull of attraction and a profound sense of unease. Can compassion find a way into the picture?

Like the Surrealists before her, Piccinini taps into imaginary aspects of the subconscious and dreams that are timeless, merging them with the extraordinary nature of the real world as well as ideas around biotechnological developments. She pays attention to intersections between the real and the artificial and, in the process, asks probing questions around human behaviour and the brave new world in which we find ourselves. What happens when we are faced with new and unexpected realities? Can we break down barriers of conventional perception? Piccinini poses these questions and invites an empathic response. She does not, however, provide easy answers but opens up a vast field of enigma reverberating into the future.

Deborah Hart

1 All quotes Patricia Piccinini, interview with author, 12 May 2017.

Patricia PICCININI

Newborn 2010

Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco Collection of Paris Neilson

Empathy for the outsider and the outcast is at the heart of Patricia Piccinini’s art. The surreal and uncanny are also integral to her practice. Across diverse media, she creates worlds in which the imagination and advances in genetic engineering come together and jostle for space. At times, in her hybrid sculptures, she recreates, merges and mutates forms into new realities, akin to the ‘monster’ of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. How we perceive such creations is cause for reflection, taking us into landscapes of heart and mind. They can be considered as meditations on beauty and ugliness and on our conditioned responses to these phenomena in a real and hyperreal world.

Patricia Piccinini challenges preconceived ideas of what constitutes beauty, exposing emotional weaknesses in human character when it comes to ideas around the boundaries between the acceptable and the unacceptable, the endearing and the grotesque. New life suggests possibility and hope.